Valentine’s Day 2012. I am a lifelong basketball nut; my wife is new to the love. We are dining at home in Toronto, talking about us, when suddenly I remember the time.

During the past two weeks, a Taiwanese American point guard named Jeremy Lin has come from practically nowhere, the bottom of the New York Knicks’ depth chart, to set the National Basketball Association ablaze. The cult of his success, “Linsanity,” is swiftly becoming the winter’s biggest sports story. Right now, downtown at the Air Canada Centre, our city’s Raptors are playing Lin’s Knicks. I leave the table expecting fireworks.

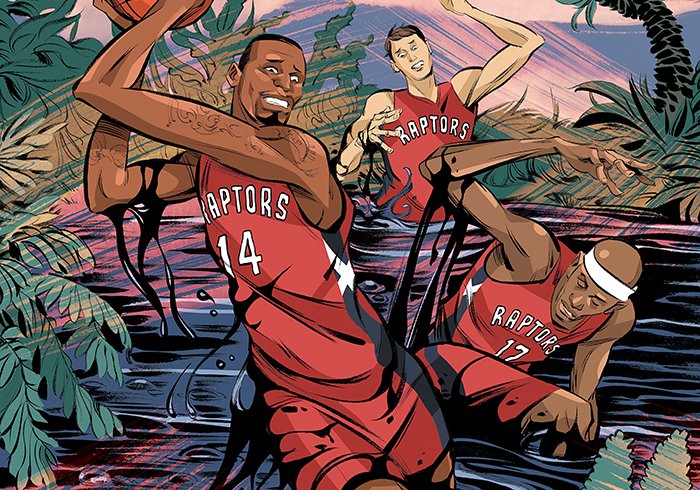

NBA basketball is waged by supermen. The average player is about six feet seven inches of fast-twitch muscle and tattoos. At its acme, the game demands speed, guile, precision, and power; elite teams attack and defend as if joined by invisible string. The Raptors, however, are unconditioned to victory. They last sniffed the playoffs in 2007–08, when they got trampled in the first round, and have mostly slumped since.

We tune in to the Knicks game with about ten minutes left on the clock. The Raptors lead by ten points, but I guess the ending before it comes. “Watch,” I mutter. “They will lose.”

And how. First, Lin ties the score with 1:05 remaining. Then, as the final seconds tick down, he calmly dribbles toward the Raptors’ three-point line. Five… four… three… Lin rises up and daggers a deep jumpshot. The ball rips the net with half a second to go.

New York 90, Toronto 87.

Months later, the Raptors finish the season in purgatory, caught midway between the playoffs—where amazing happens—and rock bottom, where the biggest losers get the best chances of restocking talent in the summer draft lottery. Stuck in the NBA’s middle is a bad place to be; stuck in the NBA’s middle and comfortable is even worse.

Yet that’s where the Raptors will find themselves again on Halloween, when they lace up their kicks to try again. Around the league, there’s a whiff of optimism about their 2012–13 roster, but around Toronto no one expects them to contend for a championship. This isn’t that kind of sports town. They’re not that kind of team.

In 1946, Maple Leaf Gardens hosted the inaugural game of the Basketball Association of America, a forerunner of the NBA. The New York Knickerbockers defeated a hard luck team called the Toronto Huskies, which folded at the end of the season. More than forty years later, local construction tycoon Larry Tanenbaum tried to bring the game back.

At the time, the world had a basketball jones. During the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games, Michael Jordan led the Americans’ Dream Team in routing the planet. The ballers were treated like rock stars. Untold millions (if not billions) of fans wanted to Be Like Mike.

With the NBA newly eyeing global expansion, Tanenbaum wanted Toronto to become its next frontier, but he failed to lure an existing team, and the league denied his unsolicited application for a new franchise. In 1993, a rival Toronto applicant, Professional Basketball Franchise (Canada) Inc., slam-dunked its bid for an expansion franchise; a Vancouver group repeated the feat seven months later.

The Toronto Raptors and the Vancouver Grizzlies made their NBA debuts on November 3, 1995. The latter lasted five years in Vancouver before decamping to Memphis, Tennessee, clearing a path for the Raptors to rebrand themselves as “Canada’s team.”

Expansion teams are expected to struggle, and the Raptors did, losing nearly three times as often as they won during their first three seasons. In late 1997, founding general manager and team architect Isiah Thomas, a legendary player whose hiring had given PBF credibility, quit the organization after a failed attempt to wrest control from majority owner Allan Slaight. Thomas’s parting gift was eighteen-year-old Tracy McGrady, a sleepy-eyed scoring savant whom he had selected in that summer’s draft.

The following year, Toronto got Vince Carter, a soaring wingman who had no use for gravity. The flashy dunk is to basketball as the home run is to baseball: a snap instance of youcannotdothis that proves the gap between watcher and watched. Carter’s excursions in the air above the rim remade the team as a premier attraction. McGrady, too, showed flashes of brilliance, though he was used sparingly, and spent long stretches of his first two campaigns glued to the bench.

The team played its first four seasons in the cavernous Rogers Centre (then called the SkyDome) while awaiting completion of the Air Canada Centre, its own temple of hoops in the beating heart of hockeyland. During construction, Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment Ltd., needing a replacement for its aging, fabled Gardens, swooped in to purchase the franchise and its unfinished arena for a reported $500 million. MLSE moved quickly to convert the ACC for mixed hockey and basketball use. When the building was finished, the hierarchy became clear: the Leafs played on their new home ice one night before the Raptors broke in their new home court.

Still, progress. In Carter and McGrady’s second full season together, the team won more games than it lost. Toronto broke into the league’s top ten for attendance, and drew large, excited crowds for the next several seasons. Carter became the NBA’s slam dunk champion in 2000. The team continued to evolve, reaching the playoffs for the first time, only to be swept in the first round. McGrady, however, was done playing sidekick. That summer, he forced a trade to the Orlando Magic, where he emerged as an All-NBA talent and scoring champion.

What once went up came whimpering down. Carter, the player who had been known as Half Man, Half Amazing, earned a shorter sobriquet: Half a Man. No other All-Star took half as long to get up after being knocked down, nor complained half as much about the pains of playing hard. In 2003, the Raptors tried to get him help, using the fourth pick in the league’s draft to acquire Chris Bosh, a power forward with a dazzling all-around game.

In theory, Bosh and a healthy, motivated Carter should have developed into a fearsome inside-out tandem, just as Carter and McGrady, playing together in their primes, could have been forerunners to Miami’s LeBron James and Dwyane Wade, the NBA’s current dominant tandem. (Those two play like twin wrecking balls swinging at the same target.) Carter, though, had already come down from the clouds. “I don’t want to dunk anymore,” he told reporters in 2004, then proved it by settling for jumpshots whenever possible. On several nights at the ACC, I joined the chorus of shouts—“Come on, man! Take him!”—lobbed at Carter whenever he settled for low-risk, low-effort shots against lesser defenders. Soon afterward, he requested a trade out of Toronto. Eight days before Christmas 2004, he was shipped to the New Jersey Nets. The Raptors were left to rebuild around Bosh.

The Bosh era was ultimately as successful as the Carter era, which is to say the team briefly threatened to become good, if not great. In 2006–07, they took their first division title. And still they lost in the first round of the playoffs, to an underdog Nets team that featured a rejuvenated Carter. It was a minor mercy that the series ended in New Jersey instead of in Toronto.

Bosh became the latest high-profile defector in the summer of 2010, landing with the Miami Heat, where he joined James and Wade to form the NBA’s most potent lineup. They became champions together earlier this year, forged by the fire of playing under team president Pat Riley, a basketball lifer who demands maximum commitment from his players, coaches, managers, and minions.

If a rising tide lifts all boats, then a shitty hockey team sinks all hope. Upon being acquired by MLSE, the Raptors inherited a culture of losing: the Maple Leafs have not hoisted the Stanley Cup since 1967. Nor have they needed to; the team is the National Hockey League’s most valuable franchise. Within MLSE, which also owns soccer’s floundering Toronto FC, winning rarely comes first. The message from the top of the organization to its managers and coaches is not win, but earn.

In professional sports, however, few championships are won without risk. For the Raptors, the greatest risk not taken remains glaringly obvious: overspending to keep McGrady, then overspending again to shape an administration capable of managing his and Carter’s expanding egos. It’s unlikely that a team with that core would have been in position to draft either Bosh or current forward Andrea Bargnani (who was a No. 1 draft pick in 2006 and has yet to play up to the standard that achievement implies), but talent functions like a magnet, and who can guess which dominant free agents would have wanted to join a Raptors team that actually lived up to its name.

After Bosh left, president and general manager Bryan Colangelo remade the team anew. If Toronto’s depleted Raptors couldn’t contend for a title, then at least they would look like Torontonians. What followed was a lineup designed to pander to a diverse, mildly interested fan base. They opened the 2010–11 season with a league-high six international players in uniform: David Andersen (Australia), Leandro Barbosa (Brazil), Andrea Bargnani (Italy), Linas Kleiza (Lithuania), Solomon Alabi (Nigeria), and José Calderón (Spain). Despite the multicultural flair, that team played like mere bystanders to excitement.

Compared with markets that attach a maximum value to winning—including major metropolises such as Los Angeles, Boston, and New York—Toronto is a low-stakes playground. The city is reportedly called “White Vegas” by the scores of ballers who flock here for off-season frolics. Carter and other departed Raptors have widely praised it for being a good home to them. The problem is not that this cannot be an NBA town but that it already is one—only MLSE has failed to convince anyone that competition is the first, middle, and last thing on its collective mind. Instead, the team is becoming less, not more, relevant to the local psyche. Toronto rarely functions like the NBA’s fourth-largest market, behaving instead like a backwater that scraps for leftovers from the league’s elite.

This season, the Raptors will feature Kyle Lowry, the toughest point guard they’ve had in years (if ever), and ex-Knick Landry Fields alongside two touted rookies: the Lithuanian giant Jonas Valančiūnas, last year’s big draft pick, and Terrence Ross, this year’s big draft pick. Even so, the ceiling on the team’s success is likely another early exit from the playoffs.

A championship sports run is a rare and special thing, one of a city’s great unifiers, though I’ve quit wondering when the NBA trophy might come to Toronto. It seems more useful to wish instead for the demise of MLSE, though it’s going nowhere any time soon, having just come under the shared control of Bell Canada and Rogers Communications, two behemoths with bad reputations for customer service. (And what are fans anyway, if not customers?)

For a brief moment this summer, however, there was faint hope. Colangelo stuck his neck out to pursue an aging Steve Nash, the two-time MVP who was raised on Vancouver Island and is the closest thing Canada has to a basketball version of Wayne Gretzky. (In fact, the team used a highlight video voiced by Gretzky in its attempt to woo Nash.) For two dreamy days in July, until news broke on Twitter that Nash would instead go to the Los Angeles Lakers, Toronto’s basketball team seemed poised to make a leap forward rather than mere incremental improvements. Instead, they remained the Raptors.

This appeared in the November 2012 issue.