In that nervous time after 9/11, many Western governments imposed draconian surveillance laws allowing them to eavesdrop on cyber-communications among suspected terrorist groups. The legislation attracted muted criticism in some corners; in 2002, Barack Obama, then an Illinois state senator, denounced the Bush administration’s Patriot Act as “unfair and unpatriotic.” But many techno-libertarians felt the scrutiny would prove irrelevant. They insisted the Internet had become too amorphous, too slippery, and too free to yield to the controlling impulses of the cyber-security complex in the United States and elsewhere.

As Ron Deibert pondered the implications of such measures –and the technologies required to enforce them—he felt far less sanguine about the Internet’s anarchic DNA. Deibert, director of the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab and the Canada Centre for Global Security, knew that many despotic regimes also collect and restrict information. “I was a little skeptical about the assumption that authoritarian governments wouldn’t be able to control the technology,” he says. In his view, it was only a matter of time before repressive regimes would begin to assert their power in cyberspace.

He was absolutely right.

The so-called war on terror did indeed give law enforcement officials in Western nations an excuse to bulk up their powers to use the Internet for tracking terrorists. For example, in 2009 the FBI arrested a man suspected of planning an al Qaeda attack on the New York subway system, based on evidence collected from his email correspondence and Internet searches (he was looking for suppliers of ingredients for explosives). But over the past several years, and especially since the Arab Spring uprisings, some of the world’s nastiest regimes have also built cyber-surveillance systems capable of minutely filtering web access while launching stealthy counter-strikes at social media–fuelled revolutions. China has built a national firewall to halt the flow of inconvenient digital information across its borders. Following the disputed 2009 election in Iran, the ruling regime arrested bloggers and imposed harsh sentences for criticizing the government online. And Syria, in addition to limiting its own citizens’ Internet access, has created a cyber-army manned by hacker soldiers who conduct electronic raids to deface or compromise foreign websites it deems hostile to the country’s leadership.

The irony is that some of the same IT systems that undergird the Internet’s liberating powers are being used to impose Orwellian restrictions of almost unprecedented reach. “Digital information can be easily tracked and traced, and then tied to specific individuals who themselves can be mapped in space and time with a degree of sophistication that would make the greatest tyrants of days past envious,” Deibert and his frequent collaborator Rafal Rohozinski note in a recent essay. “So, are these technologies of freedom or are they technologies of control? ”

The evidence, they say, reveals that we are in the throes of a new cold war, one being waged in the ethereal but indisputably contested terrain of cyberspace. While the Soviet–American conflict that simmered from the 1950s to the 1980s was marked by top secret nuclear arsenals and extensive spying, today’s global information war is an unseen, multi-dimensional conflict characterized by the use of the Internet for surveillance, control, espionage, fraud, theft, and cyberterrorism. The weapons are less explosive, but the stakes may be higher, thanks to the advent of enormously potent technologies that can disable crucial infrastructure, embarrass governments, and eradicate (or amplify) political protest.

Over the past decade, Citizen Lab, a research group focused on political power in cyberspace, has waded directly into this digital swamp. Its team of intrepid researchers—a far-flung network of advocacy-minded post-docs, human rights experts, and techies—has emerged as a kind of cyber–resistance movement. With Rohozinski and others, the lab co-founded OpenNet Initiative, a watchdog organization that has meticulously mapped efforts by dozens of repressive regimes to block access to social networking sites and those of human rights groups. Citizen Lab and OpenNet have also tracked the proliferation of web-filtering software developed by Western nations, first used by parents and educators to block inappropriate content, and now utilized by authoritarian states.

But the lab is more than just a monitor that “watches the watchers,” as Deibert likes to say. It has also quietly been helping hundreds of thousands of ordinary people living in repressive nations circumvent the silicon curtain erected by their own governments. At a time when regional economies rise or fall on the strength of innovative digital technologies (witness the wealth of Silicon Valley, and the role Nokia once played in Finland’s economy), the stakes could not be higher.

“The Internet is going through a major transformation,” says Deibert, a disheveled forty-seven-year-old with a jazz-style goatee. Billions of people in the developing world are now going online, thanks partly to the spread of web-enabled smart phones, but he surmises that their Internet experience may be far more circumscribed than the access Westerners enjoy. “We’re at a watershed moment when cyberspace could revert back to something much more tightly controlled,” he warns. “The things we take for granted can be quite fragile.”

Citizen lab, which belongs to the Munk School of Global Affairs, is situated in a hushed, light-filled space on the secured third floor of a historical sandstone building on U of T’s northern fringe. The newly restored structure was once used by the university’s astronomy department, and the cylindrical turret that housed the telescope now serves as Citizen Lab’s most prized meeting room; this affords Deibert and company a rare 360-degree perspective on the downtown campus.

The setting is ideal for a group with a mandate to look down the other end of the telescope. “The fact that it was the observatory building suits this institution perfectly,” says Deibert, whose office is under a gable and contains an antique globe that holds several bottles of exotic liquor, gifts from visiting academics. Standing in the foyer, he presses a button that deploys a mechanized shade on the skylight overhead. “It’s like James Bond,” he says with a grin, switching to a posh British accent: “Come, come now, Mr. Bond. Admit it: you like killing as much as I do.”

About a dozen of Citizen Lab’s permanent staff toil here behind banks of computer screens. (In a field dominated by men, Deibert is proud that his team consists largely of women.) But the lab’s tendrils extend well beyond its Toronto base. It has a partnership with Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, which specializes in cyberspace law and policy. Rohozinski is the other key player at Citizen Lab, with whom he and his private Ottawa company, SecDev Group, publish the suggestively named Information Warfare Monitor. (He agreed to be interviewed at first, but did not respond to several requests.)

Between them, the three organizations preside over a dispersed network of about 100 researchers and human rights activists who are embedded, ever so discreetly, in some of the world’s most dangerous and authoritarian nations. In some ways, these researchers are similar to the members of the French Resistance during World War II: they spirit sensitive information out of (or even into) these countries, often at some personal risk. “There are people with whom we have worked who have met bitter ends,” Deibert says evenly. He declines to elaborate.

As an undergraduate in the late 1980s, he studied Cold War diplomacy and set out to specialize in Sovietology, an arcane branch of international relations often taught by former spies. In early 1990, he made a thrilling pilgrimage to Berlin in the months after thousands of Germans breached the wall, that graffiti-covered symbol of Soviet repression. But a worldly thesis adviser warned him that there would likely be no more jobs for Sovietologists after the fall of Communism.

“I had no interest in being a spook,” he says, recalling how he cast around for a new direction. He enrolled at the University of British Columbia for his graduate studies, and briefly considered researching organized crime but was advised that the fieldwork could prove dangerous. Mark Zacher, then the director of UBC‘s Centre of International Relations, suggested Deibert look into the “telecommunications revolution.” Intrigued, he soon discovered that there were almost no academics focused on the impact of network technology on global relations.

This was an odd blank spot, as new information technologies have always precipitated dramatic political and social upheaval. Indeed, Deibert’s Ph.D. thesis, entitled “Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication in World Order Transformation,” explored those historical connections, noting the printing press’s role in the declining influence of the post-Reformation Catholic Church. The “hypermedia” environment of the late twentieth century, he wrote, was intertwined with globalization, because it favoured those who knew how to marshal the torrential cross-border flow of digital information to achieve commercial goals. He also paid respectful homage to Canada’s communications theory superstars, Marshall McLuhan and Harold Innis. Looking back, Deibert describes his argument as “70 percent on the mark and 30 percent hubris.”

As he completed his Ph.D., he moonlighted for a Department of Foreign Affairs research unit run by a former Canadian military officer. Its mandate: to explore the use of surveillance technology and IT networks in arms control talks. Although he never received security clearance, he got to see satellite photos from the first Gulf War in 1990–91, images so clear that he could make out Iraqis trying to bury oil drums shortly after the American invasion.

He joined U of T’s political science department in 1996, but soon found himself straining at the limitations of conventional academia. Still focused on the geopolitical implications of network technology, he attended conferences where self-styled experts prattled on about the limitless potential of the Internet while being unable to use the technology themselves. Then, in 2000, he was approached by the Ford Foundation, the New York philanthropic powerhouse, which offered him funding to establish an institute for the still-nascent field of information technology and security. The idea intrigued him, but a colleague advised him that if he sought to establish a formal centre within the university, he would quickly become mired in academic infighting and administrative red tape.

The colleague suggested that Deibert set up something more freewheeling: a political science lab. For a model, he looked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, an interdisciplinary research group that explores the futuristic culture of emerging media technologies. So, in 2001, he pitched the idea to Munk founding director Janice Stein, a well-known foreign affairs pundit and entrepreneurial academic. She loved the concept, and the lab started its work in two cramped rooms in the basement of the centre’s main building (which remained its headquarters until last winter). “The Munk School said, go, go, go,” Stein says, adding that she assured Deibert that he shouldn’t feel as if he had to deliver publishable results overnight. “We understood this was a high-risk investment.”

In 1984, on the eve of glasnost, George Soros, the Hungarian American financier and philanthropist, struck a deal with the increasingly bankrupt Hungarian government. The country had only a dozen photocopiers, which were inaccessible and heavily monitored. Soros said he would provide hundreds of photocopiers to institutions such as libraries, on the condition that they be open and allowed to be used freely. As the wily billionaire no doubt expected, the deployment of the new copiers “helped the underground press tremendously,” a friend told BusinessWeek magazine. Five years after Soros initiated the project, the Hungarian government collapsed.

That episode underscores the relationship between political power and information technology. Copyright law traces its origins to efforts by European monarchs and states to license the printing process as a means of limiting the dissemination of seditious information. In the modern era, authoritarian regimes have always sought to tightly control the airwaves and the telecommunications networks, seeing them as both tools of repression and channels for state propaganda. Those restrictions brought a technological counter-response, sometimes in the form of journalism, sometimes propaganda. BBC‘s powerful radio signals transmitted information about the Allied war effort throughout Nazi-occupied Europe. During the Cold War, Radio Free Europe and Voice of America played a similar role in piercing the Iron Curtain’s information blackout.

Indeed, one of Citizen Lab’s first initiatives was to create software that would puncture the elaborate technology shield the Chinese government had begun erecting around its citizens in 1994. In an attempt to block certain websites—everything from pornography to the New York Times—the government used elaborate filtering systems designed to intercept specific phrases, denying citizens access to those sites.

Deibert wanted his team to measure the extent and shape of China’s online suppression activities. Two programmers, Nart Villeneuve and Michelle Levesque, devised a technique for using proxy servers to test a huge number of URLs from Chinese computers. The software effectively allowed them to peer inside China’s Internet, to determine whether the authorities had blocked particular sites, and the pair surreptitiously installed the program on the network backbone of three Chinese Internet service providers. It was designed to approximate a Chinese user’s experience while attempting to access sites that included such sensitive topics as human rights, Tibet, and the persecuted religious group Falun Gong. In 2002, they reported the results: of the almost 8,900 URL categories tested, up to 20 percent were unavailable to people within China*.

In effect, Villeneuve and Levesque had hacked China’s filtering system without leaving Toronto.

More significantly, the Citizen Lab team realized that if they could write code to allow them to view the Internet from inside China, perhaps they could reverse the process; that is, allow Chinese Internet users to connect with versions of those programs installed on networks outside China, so they could visit internally banned sites. The result was Psiphon 1.0, a circumvention software program launched in 2004. The latest versions of Psiphon are web proxy systems that work like a post office box: if you don’t want to receive a particular publication in your mail slot, or if you want to keep your home address out of the hands of direct marketers, you might choose to rent a box at a postal station. Citizen Lab’s programmers create proxy sites on server space rented by ISPs that operate outside repressive regimes. They then find ways to distribute the deliberately innocuous addresses to users inside those countries. Once users log on to a proxy site, the software can be directed to retrieve web pages from anywhere on the Internet.

The sleight of hand with Psiphon was getting the site addresses into circulation in countries such as China and Iran, according to Michael Hull, vice-president of software development at Psiphon, which is now run as a stand-alone company. His team established partnerships with international news and information services—such as BBC, Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Farda in Iran—which would include URLs in the newsletters they emailed to subscribers, who then passed them around. Email messages are far more difficult to intercept than websites.

Hull’s team can’t compile a list of Psiphon users, because the software circulates freely online and was designed not to track that data. What they can do, however, is monitor log-ins from countries where Psiphon’s software is accessed. At the moment, for example, about 200,000 to 250,000 Iranian Internet users log on to its proxy sites every day.

But the circumvention software’s distribution has turned into an endless game of cat and mouse with “our adversaries,” as Hull puts it. Almost as quickly as his team creates new proxy sites, security agencies track them down and add those URLs to their filtering systems. Psiphon’s log-in graphs present almost instantaneous evidence of a given government’s activities. When the Egyptian authorities shut down the entire nation’s Internet at the height of the Tahrir Square protests in 2011, Hull says, “you’d see the graph go right down to zero.” He says his analysts knew something had happened a full twenty-four hours before the story reached the international media.

Not long after the Soviet Union suppressed Czechoslovakia’s liberal reforms during 1968’s Prague Spring, a writer and jazz enthusiast named Josef Škvorecký fled the country, taking up residence in Toronto. He and his wife, the writer and actress Zdena Salivarová, devoted their time to an audacious venture, an imprint called 68 Publishers that printed banned samizdat manuscripts by exiled Czech and Slovak authors as well as dissident residents. While the fledgling house did issue the first English translations of Škvorecký’s bestsellers for Canadian and American audiences, the couple’s main goal was getting the original language editions into print so they could be smuggled back into Czechoslovakia, where texts would pass from hand to hand, quietly eating away at the foundations of the country’s hardline government. Among their stable of authors was the jailed playwright, poet, and dissident Václav Havel, a leading figure in 1989’s Velvet Revolution, who became the Czech Republic’s first president.

Like Škvorecký (who died this past January in Toronto), Citizen Lab senior researcher Helmi Noman knows what it’s like to exist on the inside of a censorship net. A Fulbright Scholar of Arab descent, he monitors the Middle East and North Africa, which he calls “the most censored region in the world,” and he tries to keep a low profile there. “I don’t know how the censors will react to me being the OpenNet Initiative guy,” he says. Noman and Citizen Lab’s other embedded researchers function as Deibert’s eyes and ears. Deibert cites his favourite example of why it is important to have people in the field: In Uzbekistan, there were four Internet service providers, three of which had highly restrictive filtering systems. The other, they discovered, was quite open. As one of Citizen Lab’s local informants reported, that particular ISP happened to be owned by a family friend of the president—a discreet open portal for the country’s apparatchiks and oligarchs. The lab could never have known that without local contacts, Deibert says. “We want to combine technical intelligence with social intelligence.”

He likes to describe what the lab does as “sub-veillance,” or watching from below. The network is broad and loose: academics, students, human rights activists, NGO staff, and hackers, all feeding back information about censored sites, new laws, and the scope of filtering activity. “We give thought to protecting sources and setting up mechanisms so that information is compartmentalized,” he says. “If we’re compromised, it doesn’t affect the network.” But, he adds, “If something bad happened, this whole thing could go south very quickly.”

Citizen Lab looks and acts more like a mini–intelligence gathering service than a university research unit. While it espouses academe’s professed commitment to transparency and publicly debates the issues raised by its approach (a recent paper entitled “Blurred Boundaries: Probing the Ethics of Cyberspace Research” focuses on the problem of what to do with private or secret documents researchers may unearth during their digital travels), the whole operation still seems spooklike. It gives the group a distinctly non-academic cool factor, with an unmistakable hacktivist vibe. Even its published material has a far more underground, edgy feel than that of a typical university press monograph. In March 2009, Citizen Lab and SecDev Group released a blockbuster report on Chinese cyber-espionage, based on a nearly year-long investigation into online surveillance of Tibetan groups. The study, published in Information Warfare Monitor, uncovered almost 1,300 infected host computers, 30 percent of which were in embassies, government departments, NGOs, news agencies, and other “high-value targets” in 103 countries. The title borrowed liberally from the spy thriller genre: “Tracking GhostNet: Investigating a Cyber Espionage Network.”

The GhostNet findings made the front page of the New York Times, one of the world’s most visible and coveted swaths of media real estate. One expects such revelations from Interpol or Britain’s MI5, not from a bunch of academics. But in the age of Anonymous and WikiLeaks, highly sensitive digital information tends to pool in the hands of those who best know their way around the back alleys of the Internet. Deibert, who has plenty of experience dealing with journalists, has since toned down the cloak-and-dagger references when talking up the findings. The intense coverage made him realize that Citizen Lab was now on the radar of many organizations and governments—some of them unfriendly. “If you expose one of the [world’s] larger cyber-espionage organizations,” he muses, “you become a cyber-espionage organization.”

In 2000, Iranian journalist Hossein Derakhshan moved to Toronto to study sociology at U of T, and soon began blogging in Farsi about technology and politics. He quickly gained a sufficient following back home that he published an online how-to guide about blogging in Farsi, and he became known as the Persian “blogfather,” renowned among Iran’s young, technologically literate population. While his blog was subsequently blocked by the Iranian authorities, he publicly defended the regime’s bid to develop a nuclear program and protect itself against the threat of a US attack. Despite writing some clearly pro-Iran columns (including one published in the Washington Post), he was arrested in 2008 while visiting his family and charged with propagating criticism of the regime. It was reported that he was initially threatened with the death penalty, and he is now serving nineteen and a half years in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison.

Urban Iranians know the blogfather story well. Indeed, there is a network of local Farsi speakers linked to Deibert and Psiphon, and OpenNet/Citizen Lab are currently working on a country report on Iran, a scorecard document published by human rights organizations such as Amnesty International. Among other issues, the team is focusing on the growing risks faced by bloggers, especially now that Iran has promulgated a sweeping new cybercrime law. I was sent a translation by one member of the team, and the language is chilling: it criminalizes content that offends “public morals and ethics,” “Islamic sanctities,” “public security and welfare,” and so on. As Derakhshan discovered the hard way, Internet censorship in Iran doesn’t stop at filtering and blocking; it sometimes culminates in the prosecution and torture of those who dare to express themselves online.

The blogging story in Iran turns out to be both intriguing and anomalous by the standards of many Middle Eastern countries. Iran has a well-educated and culturally sophisticated population, especially in Tehran. Moreover, its Internet usage rates are far higher than in many other nations in the developing world, partly because of an innovative ISP sector. During a period of liberalization under former president Mohammed Khatami, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, state officials encouraged greater freedom of expression, and resisted imposing controls on Internet use because they saw it as a tool for economic development. Meanwhile, the religious authorities, who wield enormous influence, shut down several newspapers, and many newly unemployed journalists took to the blogosphere. By 2008, an estimated 60,000 blogs were being written in Farsi, thousands of them inspired by Derakhshan and openly critical of the government.

Under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, that openness has been rapidly disappearing, especially in the wake of the 2009 Green Revolution, and much of the cyber-activism in Iran has now gone underground. Indeed, Citizen Lab’s colleagues at Harvard’s Berkman Center have been trying to determine how many of those 60,000 bloggers are still posting under their own names.

Overseas, Helmi Noman, like Citizen Lab’s other field researchers, has been building on this legwork by using a specially developed software tool to quantify the extent of official blocking activity. The software—”a client”—is loaded onto a computer in the target country. The program contains two long sets of web addresses, a global list and a local one. The former includes everything from Facebook and Twitter to international news and human rights groups, and even porn and dating sites. The local list, compiled by field researchers in each region, includes political blogs, dissident group sites, and other addresses that might fall under scrutiny. Deibert says repressive governments tend to worry more about the local sites, because the most pointed and potentially destabilizing political criticism invariably comes from within.

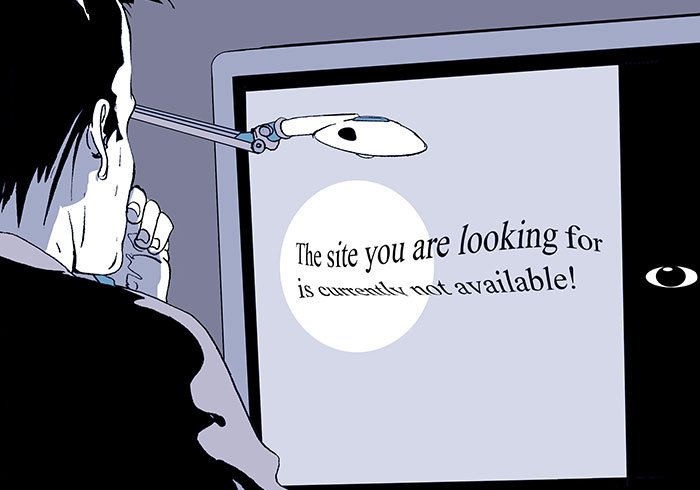

When the software client is activated from within a target regime, it automatically visits the sites on both lists; meanwhile, Citizen Lab’s computers in Toronto go to the same addresses. One discrepancy the team repeatedly observed was that a Canadian computer could access a human rights page, for instance, while its counterpart in the other country would encounter a blocked-site screen instead. “The practice of censorship is very visible to the rest of the world,” Noman says, but not necessarily inside the country in question. In Yemen, for instance, users trying to view sexually explicit content receive a page stating something along the lines of “The site you are trying to access is blocked.” But when they attempt to visit a blacklisted political site, they receive an error message instead. The state-run ISP does this to deliberately mislead the users into thinking the political sites are not blocked, do not exist, or are having technical problems. The authorities do not want to admit to political filtering.

Interestingly, some blocked-site message pages include the name of the company that has provided filtering software to the ISP that delivers the connection to local users. Several are private Western firms that appear to have tapped in to the burgeoning market for censorship systems. In 2009, Noman’s team discovered that technology developed by an American cyber-security company called Websense was installed on ISPs in Yemen. The Wall Street Journal published similar revelations about a range of other Western businesses, including a company now owned by McAfee, the well-known computer security firm whose virus detection software is housed on millions of desktops, smart phones, tablets, and other devices worldwide. As an OpenNet report stated, “Western-made tools for the purpose of blocking social and political content are effectively blocking a total of over 20 million Internet users from accessing such websites.”

When the Citizen Lab/OpenNet group exposed Websense, the company contritely announced that it would withdraw from the political censorship market. Afterwards, Noman says, “we noticed the system wasn’t catching new objectionable content.”

Not long after Websense pulled out of the Middle East, filtering technology from another company turned up on computers in Yemen, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates: Netsweeper, a Canadian company founded in 1996 by entrepreneurs Perry J. Roach and Lou Erdelyi. Netsweeper had ridden a fast-rising wave of demand for its products—the global Internet security industry, which does everything from sweeping viruses to building complex firewalls around corporate and government websites, was worth $75 billion in 2011—and had even opened a support centre in the Middle East. (Netsweeper officials did not respond to an interview request.)

At around the same time, Jakub Dalek, Citizen Lab’s twenty-seven-year-old systems administrator in Toronto, was poking around networks in Myanmar as he tracked down similar leads on a large California company called Blue Coat, whose web-filtering system had turned up in that country. Dalek, a lean and dishevelled U of T political science grad who looks like a hacker right out of central casting, had set up a complex monitoring system and discovered, almost accidentally, that Blue Coat’s filters were also installed on the Syrian ISPs he watches. He conducted tests of those systems and found evidence of Blue Coat’s software in what was effectively an unsecured corner of a Syrian IT network.

One of the world’s largest Internet security companies, Blue Coat has over 15,000 clients, including universities, school districts, private hospitals, and even communications giants such as Thomson Reuters. The $490-million-a-year firm, whose stock used to trade on NASDAQ, plays up a certain new-sheriff-in-town pose. Its product line includes K9 Web Protection, a filtering program for home computers; and PacketShaper, a so-called deep packet inspection tool, which, according to Blue Coat’s website, provides its corporate and government clients “the X-ray vision needed to monitor today’s network traffic, and enforces your rules with priority, partition, and rate control technologies.” (In other words, PacketShaper does not just block restricted sites; it can detect the content of any site an employee visits while using an employer’s computer.) Blue Coat has a Canadian connection: in February, an investment group that included Thoma Bravo, a San Francisco private equity firm, and the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan acquired all of the company’s shares for approximately $1.3 billion.

Citizen Lab was not the only one sniffing around Syria’s network. Between the spring and fall of 2011, French and Swedish hacker groups went public with further revelations about the extent of the connection between Blue Coat and the Syrian government. The Washington Post reported on the company’s denial that it had sold software to Syrian officials, a transaction that could have violated US sanctions. Deibert remains skeptical of Blue Coat’s claim of innocence, because its hub computers constantly send updates to its clients’ systems. “How could it lose track of devices that were checking back with the home base? ” he asks. (Some ISPs in repressive states are now taking the precaution of removing the name of the company that provides their filtering software.)

What makes the discovery of Syria’s use of Blue Coat software intriguing is that the lab had not set out to investigate the firm. “It was a slowly brewing thing,” says Deibert. The team’s modus operandi, he says, is improvisational: when one team member finds something interesting, he or she will set up an internal web page, and others will start to post ideas, suggestions, and new findings, which is what happened with Syria last fall. Indeed, as the Blue Coat story gathered momentum in 2011, Helmi Noman, the lab’s regional coordinator for the Middle East and North Africa, intensified his focus on the Assad regime, scrutinizing Syrian government websites and Internet protocol addresses, the unique numeric codes that locate every computer linked to the web. One was Canadian. “You kick in like an investigation at that point,” Deibert says.

A devastating revelation opened up at the other end of the wormhole Noman had decided to explore. As Citizen Lab reported last November, Canadian servers were hosting seventeen Syrian websites, including those of several government agencies, and Addounia TV, a station closely linked to the Assad regime and sanctioned by Europe and Canada for inciting violence. (In the same report, the lab also revealed that the website for the official media arm of Hezbollah, the Lebanese political party, which Canada classifies as a terrorist organization, was hosted on Canadian servers.) This news came at the tail end of a year when the embattled Syrian regime had killed over 3,500 of its own citizens in an attempt to thwart a mounting pro-democracy opposition movement.

These findings, Citizen Lab noted, raise a raft of ethical, legal, and policy questions. The Syrian regime’s patronage of domestic web hosting services is “in contradiction to Canada’s stated foreign policy with regard to the ongoing violence in Syria, and possibly [provides] material support to a regime that is engaged in systematic violence against peaceful demonstrators.”

Aliya Mawani, a spokesperson for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, offered this comment: “We expect all Canadian companies working abroad to abide by international laws, and to uphold the highest ethical standards. Canada and our G8 partners at Deauville are committed to working together to ensure that the Internet is kept open, safe, and accessible. The Government of Canada will not pursue initiatives that run counter to that spirit.”

It is interesting that a Cold War-era invention—the Internet, developed by the US Department of Defense for sharing research data—is not only the defining technology of the post-Communist period, but has also given rise to the next phase in the long, sorry tale of human conflict and domination. Indeed, the advent of the personal computer and email overlapped neatly (and surely not coincidentally) with the decline of the Soviet empire, which clung to the idea that it could control information and thus limit citizens’ exposure to the West’s temptations. By the time Mikhail Gorbachev launched perestroika and glasnost, the communications technology revolution was churning powerfully, and the commissars’ attempts to block inconvenient truths were foundering.

The new cold war, like the old one, is mostly (though not entirely) a bloodless affair, in which much of the violence is perpetrated secretly against those who seek to challenge authority. The current era’s weapons of mass destruction are no longer hidden in silos in wheat fields. Rather, they are lethal viruses launched at foreign government and corporate IT networks by invisible hacker cells. But the arsenal also includes devious tools of government repression directed inward—the digital successor to East Germany’s network of Stasi informants who spied on their neighbours and co-workers. Instead of employing musty filing cabinets stuffed with gossip-filled dossiers, the new cold war uses Google search records, Twitter accounts, and Facebook pages to incriminate individuals. Blogs have taken the place of basement samizdat presses, and jerry-built routers equipped with filtering devices have automated the work of censors.

WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange is indisputably the George Smiley of this modern cold war. And perhaps Iran’s blogfather will someday become that country’s Václav Havel, martyred for expressing politically threatening opinions, albeit in a different medium. What remains unclear is whether the information wars of our age are just beginning, and whether the Internet’s exceptional technical resilience is prevailing over government-sponsored attempts at digital censorship. Will China’s Great Firewall crumble in the face of countless attempts to breach it? And does demand for enabling technologies present an irresistible market opportunity for IT entrepreneurs?

Deibert says the Internet’s vastness may lull us into a false sense of complacency about how the story plays out. The roster of countries locking down portions of the web is growing. To combat that trend, the lab made a formal submission last year to the United Nations Working Group on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations, urging “greater assessment of, and provision of guidance to, the surveillance and Internet filtering technology sector. Companies in this industry,” the brief continued, “have thus far demonstrated a serious lack of regard for the negative human rights impacts of their products and services. In general, company reactions to allegations concerning compromise of human rights suggest an absence of company policies and due diligence measures to identify or prevent such abuses, let alone mitigate or remedy them.”

The US government and some EU countries are considering legislation to impose tougher restrictions on the trade of technologies that can be used to undermine human rights. The Canadian government, however, has done nothing more than sign on to high-level G8 communiqués. That equivocating silence is frustrating, Deibert says, and at odds with Canada’s substantial intellectual contribution to an open global communications environment—a tradition that stretches from Bell to McLuhan and onward to that converted observatory the Citizen Lab’s hacktivists call home. “We need to create a robust, secure, but free and open communications system for the planet,” Deibert tells me. But, he says, “We have no moral basis if we can’t do it here. That’s why Canada is failing the world.”

To put it another way: when you are watching the watchers, you should take a look in the mirror.

[breakline]* The printed version of this story miscalculated information from Villeneuve and Levesque’s report. The Walrus regrets the error.

This appeared in the June 2012 issue.