Last January, U.S. President George W. Bush and Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin apparently hit it off over a breakfast of sausages and eggs at the Summit of the Americas meeting in Monterrey, Mexico. The president is quoted as saying that Martin is “a straightforward fellow and easy to deal with.”

The prime minister, for his part, declared his wish to improve Canada-U.S. relations even before he was sworn in on December 12, 2003. But, as he moves toward improving those relations, Martin must reckon with the fact that his predecessor’s arm’s-length approach met with the approval of a substantial majority of the Canadian population. Martin, therefore, faces an impressive set of challenges on this front. How to signal sympathy for America’s post-September 11 position without leaping on a bandwagon of militarism, unilateralism, and paranoid domestic security? How to cultivate the economic ties that sustain us while maintaining Canadian sovereignty? How to pursue an agenda, both domestic and international, that reflects Canadian values without affronting our powerful neighbour to the south? Moreover, Martin must juggle the fact that an American election has begun rolling out. Commitments to this president may prove premature should the U.S. administration change come November. Either way, the next six months will be no cakewalk for Martin.

Managing Canada’s ties with the United States has always been a challenging part of the prime ministerial job description. And yet, as the Canadian comic Rick Mercer observed recently, living next to the United States right now is like “being in a pen with a wounded bull.” Part of what makes the beast thrash around has to do with what many critics of the American administration have called the “culture of fear.”

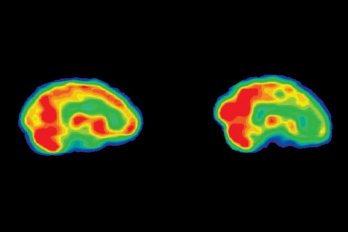

Although this culture has been most palpable during the past couple of years, it did not, in my view, emerge from the rubble of Ground Zero. In fact, my research shows that the roots of the present malaise long preceded September 11. America has demonstrated growing levels of technological anxiety, fear of complexity, fear of the “other” (in the form of sexism and xenophobia), and fear of violence, at least since the early nineties. In September, 2001, these fears took centre stage and were undoubtedly exacerbated, but they were hardly a new phenomenon.

In the years before the collapse of the Twin Towers, Canadians were measurably less anxious than Americans in many respects. Since then, our attitudes and policies have diverged from those of our neighbours even more sharply. That does not mean we are exempt from the pitfalls associated with a fearful and defensive world view. We have our own version of the American culture of fear. We obsess not over religious fundamentalists halfway around the world, but over America itself.

It has often been observed that the crudest form of Canadian nationalism is anti-Americanism. As he massages Canada-U.S. relations, Paul Martin will have to draw a clear line between conciliation and cowering, assuring Canadians and Americans alike that Canada’s renewed friendship with the United States is rooted neither in fear, nor in a petty contrarianism born of fear. He will in fact have to put forward a new vision of partnership and in this, he may draw strength from the words of former U.S. president Richard M. Nixon. Speaking to the Canadian parliament in 1972, Nixon claimed that “mature partners must have autonomous independent policies; each nation must define the nature of its own interests… decide the requirements of its own security… the path of its own progress.” “The soundest unity,” Nixon went on to say, “is that which respects diversity, and the strongest cohesion is that which rejects coercion.”

There are at least three domains in which Martin might find opportunities to advance the repositioning he seems eager to implement: the first is the personal relationship between himself and the president, a domain in which Martin has already had some success. The second is in the myriad agreements and interactions between the two countries which are not politically charged: the minutiae of the relationship that do not diminish Canadian sovereignty or threaten Canadian values. The third relates to policy issues intimately connected to deeply ingrained Canadian values. It is in this final area that Martin will have to walk the narrowest line.

Relationships between Canadian prime ministers and U.S. presidents have always been fascinating, unfolding as they do in tandem with historical events, yet consisting of many of the same idiosyncrasies that attend any interpersonal relationship. Canada has had prime ministers with cool, even hostile, relations with American presidents. In the early 1960s John Diefenbaker and John F. Kennedy could hardly stand each other. JFK’s brother Bobby once complained of Ottawa’s equivocation during the Cuban missile crisis, “In an emergency Canada will give you all aid short of help.”

But there have also been times when Canadian prime ministers were very close to their U.S. counterparts: William Lyon Mackenzie King and Franklin D. Roosevelt were friendly in the 1940s, and Brian Mulroney was cozy to the point of controversy with both Ronald Reagan in the eighties and George H. W. Bush in the early nineties. Indeed, White House memos from the mid-eighties (released in the late nineties) reveal that American officials were instructed by advisers to make a few well-publicized concessions to Mulroney, in order to avoid having the Canadian P.M. look like a “lackey” in the eyes of his own citizens.

The most dramatic tête-à-tête between a U.S. president and a Canadian prime minister may have been a famous incident at Camp David in 1965. Lyndon Johnson, enraged by a speech Lester Pearson had just delivered at Temple University in which he criticized America’s involvement in Vietnam, allegedly grabbed the Nobel Prize-winning Canadian by the lapels and, to the horror of nearby aides, bellowed: “You pissed on my rug.”

Lawrence Martin, the journalist and author of The Presidents and the Prime Ministers, claims that, “If you have a high level of communication, that spirit gets channelled down through the system and [the countries] work in a more co-operative vein.” This may have been truer when we were more deferential to our leaders; today there is a lot less latitude for prime ministers and presidents to co-operate if it means ignoring or opposing the values and perspectives of the coalition of voters that put them in power. At any rate, Michael Kergin, the Canadian ambassador to the U.S., has recently stated that he does not believe that much will change whether Paul Martin succeeds at fostering a better relationship with George Bush or not. “The U.S.-Canadian relationship is too important to be affected by any one person,” Kergin says.

Under Martin’s watch, Ottawa-Washington relations already seem better lubricated: the U.S. administration says that Canadian firms can now bid on projects to rebuild Iraq, and has also agreed to consult Canadian officials when American authorities seek to deport a suspected terrorist with a Canadian passport to a third country.

The second area in which Mr. Martin could make conciliatory gestures toward the United States is in the two countries’ quotidian interactions – legal, economic, political, and socio-cultural. Much of the Canada-U.S. relationship is constituted of the kind of workaday exchanges that have little or no symbolic meaning to most Canadians (or Americans for that matter). As last year’s spectacular blackout reminded us (or informed us for the first time), we share some important infrastructure with the United States. We also share a tremendous amount of unproblematic trade (about $1.4 billion per day): softwood lumber and beef cattle are exceptions to the rule. We co-operate on plenty of mundane issues of law enforcement. Many of our shared projects in this domain have nothing to do with the symbolically charged war on terror. Canadian separateness and sovereignty do not hang in the balance at every turn in these quotidian negotiations.

Despite much hand-wringing north of the border (particularly from the Left), my research suggests that economic integration has done very little to erode Canadian values. On the contrary, our values are increasingly diverging from American social values. In my recent book Fire and Ice: The United States, Canada, and the Myth of Converging Values, I document the growing gap. In surveys my firm conducted among representative samples of Americans and Canadians aged fifteen or over in 1992, 1996, and 2000, we found Americans much more likely to embrace the social-conservative agenda, including religiosity and patriarchy. Canadians, on the other hand, are more likely to espouse the core values of social liberalism, including a questioning of traditional religious authority and a rejection of patriarchy. Although our surveys in the United States were performed only at the four-year intervals noted above, our surveys in Canada were undertaken annually; Canadian social change in the 1992–2000 period was relatively steady. The adoption of nafta, in 1994, had no obvious effect on social values north of the border.

This observation is not intended as a call for complacency. There is no question that sharing a very long border with the world’s only superpower, whose wealth, military might, and population dwarf our own, poses unique challenges to our sovereignty. But when John Turner’s admen warned us in the 1988 general election that the Canada-U.S. free-trade deal would in effect eliminate the border, destroy our beloved public health-care system, and obliterate any semblance of Canadian sovereignty, they were simply wrong.

Public-opinion polls show that the majority of Canadians still believe that our country’s values and lifestyles are converging with those of Americans. My research shows quite the opposite. Why the discrepancy? Whereas public-opinion polls focus on the pulse of a constituency, document what people think is happening, or what they believe should happen in the world of public affairs, my surveys measure what people admit to be their own personal values: the mental postures that guide them through their everyday pursuits. Canadians are, of course, free to imagine what they like about the Canada-U.S. relationship, but I would contend that those who claim Canadians are becoming more like Americans are simply mistaken.

The third prong of Martin’s scheme for Canada-U.S. relations must involve the protection of those policies that are most closely linked to our essential values. It is one thing to bend in a trade dispute, or even beef up border controls to satisfy Tom Ridge and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Certainly, there are principles at stake in these areas, and no one likes to be bullied. But if Martin is wise, he will shore up favour with his American counterparts, so that he can underscore Canadian sovereignty in policy areas that are inextricably linked to distinct Canadian social values.

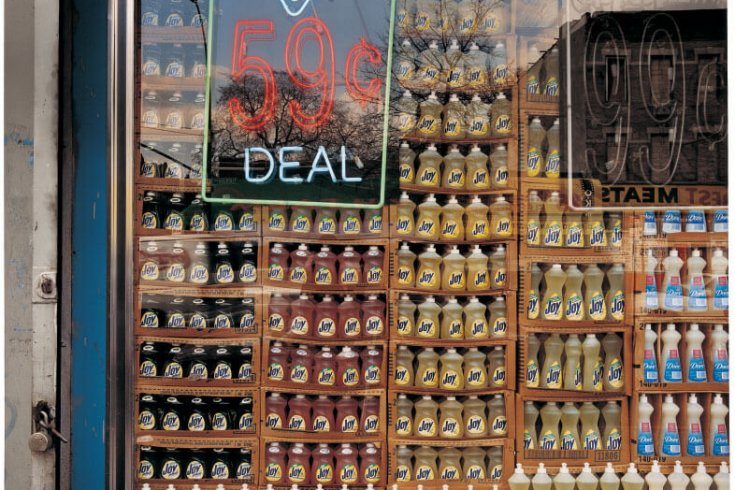

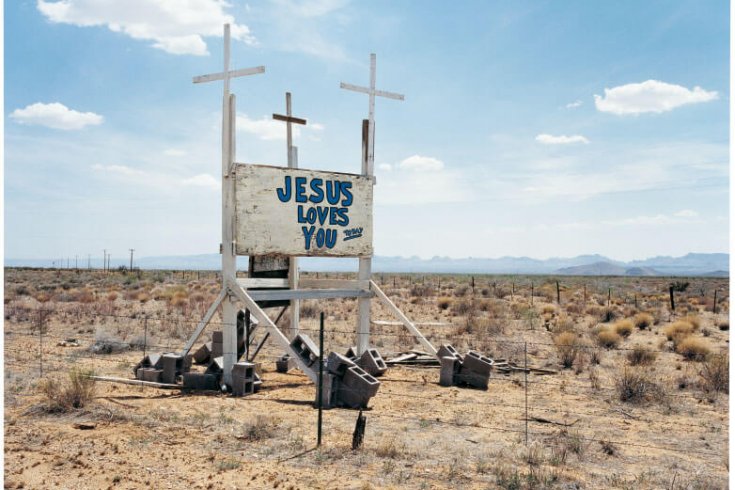

Two areas of particular divergence between Canada and the United States in terms of social values are patriarchy and religiosity. More than two in five Americans say they go to church weekly, compared to less than one in five north of the border. Two-thirds of Americans say religion is important to them, compared with one third of Canadians. More than thirty percent of Americans claim to believe that the words of the Christian Bible are literally true, while only fifteen percent of Canadians agree.

Canadians also have more confidence in their ability to make moral decisions without deferring to religious authority. The Pew Research Center, based in Washington, D.C., recently released a report which revealed that fifty-eight percent of Americans hold that it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral. The number of Canadians who draw an ineluctable link between God and morality amounts to only thirty percent. These results are particularly interesting because they reveal that most Americans not only rely on religion as a framework for understanding personal experience, but also depend on religious concepts and ideas to ground their immediate reactions to events.

The data I’ve collected reveal a high correlation between patriarchy and religiosity. The devoutly religious – and the devoutly Christian in particular – are much more likely to agree with the statement “the father of the family must be master in his own house.” Consistent with their stronger religiosity, Americans are more than twice as likely as Canadians to hold such convictions: nearly half of Americans say they believe that the father must be the master of the house, as compared with fewer than two in ten Canadians. In America, support for patriarchy is increasing steadily (it rose seven percent during the 1990s) while in Canada it is declining just as steadily. Even in Quebec – staunchly Roman Catholic not so very long ago – weekly church attendance is now actually lower than in the rest of Canada. And declining support for patriarchy there has accompanied the exodus from the pews: barely one in seven Quebeckers still thinks dad must be king of the domestic castle.

Both Canadians and Americans are deeply attached to the idea of family. But while Americans are more likely to believe that the only legitimate family configuration is two parents of the opposite sex and children, Canadians are more open and receptive to diverse family arrangements: single parents and common-law and same-sex partnerships, with or without children. Nor are religious and patriarchal values important only around the house. They have implications for the work-place, the consumer marketplace, and in matters of public policy. In 1982, gender equality was entrenched in our Charter of Rights and Freedoms; in the same year the Equal Rights Amendment lapsed in the United States. In late January, 2004, our Supreme Court placed restrictions on the parental use of severe physical force. Though the language of the decision was criticized for leaving too much to interpretation, the spirit of the decision was certainly in line with Canadians’ declining belief in patriarchy and related models of strict child rearing. The U.S. courts have yet to make such rulings.

Of course, there are many Americans who reject patriarchy and are not very religious – from one-third to one-half – depending on the issue. But their numbers are stagnant; for decades progressive Americans have been on the political defensive – a losing position that has worsened since September 11. For American liberals, Canada has gone from being irrelevant and cold to inspirational and cool. Indeed, the Canadian federal government’s recent legislative moves related to marijuana and same-sex marriage inspired Hendrik Hertzberg, a senior editor at The New Yorker, to remark that Canada has become the kind of country that, “makes you proud to be a North American.”

I believe that Canadian and American values have been going their separate ways since the 1970s, when Americans concluded that their government had failed to win the War on Poverty, mandated disruptive bussing to achieve racial integration, led the country to a humiliating defeat in Vietnam, deceived the populace with Watergate, stood helpless in the face of skyrocketing fuel prices, and presided over the subsequent economic “stagflation.” In that pivotal decade, Americans decided that government was the problem, not the solution.

In the same decade, Canadians came to believe the opposite: that government could be trusted to solve their problems. In 1976, Canada’s parliament abolished the death penalty; in the U.S. thirty-eight of fifty states still practice capital punishment today. In 1980, Americans elected Ronald Reagan, and we re-elected Pierre Trudeau, ushering in a decade of unparalleled activism. In the late nineties Canada established a (costly) gun registry; at the same time, Los Angeles prohibited its residents from purchasing more than one gun a month.

The policy areas that most strongly express Canadian values are reflected in our social safety net, our universal health-care system, and our multilateral approach to international relations. Many Canadians see these as the aspects of our country that differentiate us most clearly from the United States. And it’s these policies the government must treat with the greatest care.

The area in which there is the greatest potential for U.S. pressure on Canada is, of course, international relations. As Canadians demonstrated in their response to the Iraq war, we are far from ready to abandon our traditional commitment to the “soft power” of multilateralism. The moralistic narratives of absolute good and evil that win many hearts and minds south of the border don’t work in Canada, where pragmatism has always trumped ideology. If George Bush is re-elected, and chooses to apply pressure to Iran, Syria, and North Korea, Paul Martin will have great difficulty offering any support without raising the ire of the Canadian people. Any effort at “régime change” that Canadians would approve would have to be idealistic, humanitarian, and free from any taint of U.S. commercial self-interest.

Though our domestic behaviour is of much less significance to the U.S. than is our role in the international arena, it is nevertheless instructive to see how Canadian and American social values inform big policy decisions in, for example, the area of social spending. The primary destination of such spending in the United States is education. The American assumption is that everyone should get a fair crack at public schooling; anyone who fails is guilty on a very personal level. Individuals who do not seize the day are only entitled to minimal further assistance.

In the United States – particularly since Bill Clinton’s Republican-endorsed welfare reform in 1996, help for the poor has been doled out, or withheld, as if by the hand of a strict father. U.S. welfare reform was intended to kick-start lives – but in fact it was a kind of triage: a portion of those on welfare before 1996 did, indeed, pull themselves up by the bootstraps; a portion remained on the dole, and a portion simply disappeared.

In this country things are different. The Canadian welfare system is commonly given a more dignified name of social assistance, and it is not handed out in a strict, patriarchal manner. We handle our poor rather more magnanimously than in the U.S. But what is perhaps most interesting about the Canadian welfare program is the fact that our poor are treated in much the same way as other minority groups – regions and provinces and so on. We accommodate them, and, whether criticisms can be made of particular policies from province to province, at least attempt to bring them into the fold. In Canada, welfare is not exploited as a disciplinary action but treated as an investment in social capital.

Of course, shared responsibility has always been cast as the ideological counterpoint to individual advancement. But it is increasingly the case that Canada, France, Germany, and the Nordic European countries, which have tended to emphasize shared responsibility, do a better job than the United States of providing a landscape in which social mobility is possible. In the European countries mentioned, a child born into poverty is six times more likely than a poor American child to escape that poverty during her lifetime. Socio-economic mobility – the American Dream of moving from rags to riches – is more of a reality and less of a dream in Canada than in the United States.

Inevitably, Prime Minister Paul Martin will find it necessary to make concessions to the U.S. But given Canadians’ commitment to a distinct set of values, he will be able to discover a very limited horizon in which he could transform Canada into a fifty-first state.