By the end of the Liberals’ first term, in 2019, Justin Trudeau’s public image had been tarnished by a series of missteps and controversies. The prime minister faced controversy over a late-2016 holiday on the Aga Khan’s private Caribbean island, violating federal ethics laws. In 2018, his India trip drew criticism for Bollywood-like attire and the inclusion of Jaspal Atwal, a convicted attempted murderer, at a dinner reception. Then came the blackface scandal: during the 2019 election, Time published a 2001 photo of Trudeau in blackface at an Arabian Nights gala, a humiliating revelation that made international headlines.

None of these incidents, however, was as damaging as what would become known as the SNC-Lavalin affair. On February 7, 2019, the Globe and Mail reported that Trudeau and his staff had inappropriately pressured former justice minister and attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould to defer the criminal prosecution of Quebec-based engineering giant SNC-Lavalin, which was facing fraud and corruption charges related to nearly $48 million in payments made to the Libyan government. Testifying before the House of Commons justice committee later that month, Wilson-Raybould said she’d experienced “veiled threats” and “a consistent and sustained effort” by senior government officials seeking to convince her to interfere in an independent criminal prosecution.

Ultimately, both Wilson-Raybould and her close friend Treasury Board president Jane Philpott—two women Trudeau had formerly held up as star ministers in his gender-equal cabinet—resigned their posts, saying they had lost confidence in the government. It wasn’t a good look for a prime minister who regularly touted his feminist bona fides—and it put some cabinet members in a difficult position with constituents looking for explanations.

Chrystia Freeland, for her part, chose not to wade into the murky waters. As deputy editor of the Financial Times a decade and a half earlier, she had not had a critical word to say against her boss, Andrew Gowers, even after it became clear that the newspaper was struggling under his leadership and that his days as editor-in-chief were numbered. Now, as foreign affairs minister, Freeland afforded the same loyalty to Trudeau, expressing in interview after interview her absolute confidence in the prime minister. The day after Wilson-Raybould’s testimony, Freeland told CBC Ottawa Morning that while she believed her colleague had spoken “her truth,” she was “very clearly of the view that the prime minister would never apply improper pressure.”

Freeland’s robust defence of her boss failed to convince many pundits of Trudeau’s trustworthiness—in an opinion piece for CBC News, for example, Robyn Urback called it “obsequious blather.” But those who know Freeland say it’s unlikely she would suffer a “fake feminist,” and indeed, from his first attempts to convince her to join Team Trudeau, the prime minister had shown unequivocal support for her as a working mother. If Freeland had doubts about the man she worked alongside every day, she was keeping them to herself.

That changed earlier this week, when Freeland unexpectedly announced her resignation from cabinet, citing irreconcilable differences with Trudeau over key policy decisions. The resignation, on December 16, came hours before she was scheduled to deliver the fall economic statement. It marked a dramatic turning point in her relationship with the prime minister. Once seen as his staunchest ally, Freeland was both Trudeau’s defender and his problem solver. Her departure not only fuels speculation about deepening fractures in the Liberal team but brings fresh scrutiny on a figure who had been viewed as the party’s future.

While Liberals were re-elected on October 21, 2019, the results showed a country split along regional lines. The party performed well in Ontario, but the Conservatives swept the Prairies—not one Liberal MP was elected in Alberta or Saskatchewan, where frustration with the federal government’s energy policies had been mounting. Separatist voices began calling for the independence of Canada’s four westernmost provinces, a so-called Wexit. Faced with this new challenge, Trudeau called on his most trusted minister. On November 21, when Trudeau unveiled his new cabinet, Freeland was appointed to intergovernmental affairs—one of the trickiest files.

In a CBC interview after her swearing-in, Freeland describes herself as a “grateful daughter of Alberta.” With her Prairie roots—she grew up in Peace River and Edmonton—and propensity for coalition building, it was clear she was Trudeau’s best hope for bridging the growing divide between the federal government and the provinces’ mostly conservative premiers. But while the intergovernmental affairs brief would have been enough to keep a minister’s hands full, Trudeau also appointed her his deputy prime minister. It was the first time since 2006 that a leader had chosen to fill the position. In the past, the duties associated with the posting had varied, depending on the prime minister. While some former deputy prime ministers played a more ceremonial role, Trudeau seemed to see Freeland in much the same way as former prime minister Brian Mulroney had viewed his deputy, Albertan cabinet minister Donald Mazankowski: as the government’s “chief operating officer.”

Freeland’s mandate letter listed an eye-popping number of tasks: on top of her intergovernmental affairs responsibilities, she was expected to see the new North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA, through to legislation and continue to oversee the Canada–US file; work with her ministerial colleagues on strengthening medicare, transitioning to a green economy, introducing a national ban on assault rifles, and laying the groundwork for a national child care system; and sit on various cabinet committees. “Are you not taking on too much?” CTV Power Play’s Don Martin asked in an interview. “Your kids are going to ask for ID when you walk in the door.”

“I like working hard,” she replied, joking that her children had seen quite a bit of her during the election campaign and wouldn’t mind a break from her cooking. Plus, she added, she hadn’t taken on the job to be a “spokesmodel.”

Following the appointment, Trudeau and Freeland began to meet every week at 80 Wellington to go over agenda items. At first, their interactions were a bit awkward. Conversation could be stilted, with neither quite sure where to start. The staff who accompanied Trudeau and Freeland to these weekly “bilats,” as they referred to them, felt almost as if they were parents bringing two teenagers on a date, prompting them to ask each other about their weekends to get the discussion going. But before long, the two became much more at ease with each other. “The prime minister and I felt like we came up with a successful way of working together on a really difficult negotiation known as NAFTA, and we’re going to take that approach and bring it to bear on our big national challenges,” Freeland told CBC Radio’s The House.

Of course, in politics, as in life, the best-laid plans are at the mercy of the unexpected.

On January 23, 2020, Chinese authorities sealed off Wuhan, a city of 11 million people, ordering a strict lockdown for residents and cancelling flights and train travel in an effort to contain the outbreak of a mysterious pneumonia-like illness. But it was too late. Cases of what the World Health Organization referred to as a “novel coronavirus”—COVID-19—had already spread to other countries in Asia and Europe and to the United States. By March 11—with more than 118,000 cases in 114 countries and nearly 4,300 dead—the WHO declared that the world was facing an unprecedented pandemic.

As chair of the government’s newly created cabinet committee on COVID-19, Freeland became the point person for the government’s response to the pandemic. As the virus threatened countries with economic disaster, pushed health care systems to their extreme limits, and upended the lives of billions of people around the globe, she let people know that she’d be relying on the same consensus-building approach that she’d used so often in her life and political career. “This is a whole-of-government, indeed a whole-of-country, effort,” she told reporters. Freeland was “extremely involved in speaking to her fellow ministers,” according to a government official. She also worked closely with provincial premiers, building an unlikely friendship with Ontario leader Doug Ford, whom she called her “therapist.”

“Freeland’s the one who grabbed me by the collar and said, ‘Get it done.’”

By mid-March, businesses and schools across Canada had shut their doors as people were instructed to stay home to save lives. Freeland’s experience of the lockdown would differ from that of most Canadians. When so many were forced to stay home from work, she continued travelling back and forth between Toronto and Ottawa, replacing her usual Porter Airline flights with long drives along the Trans-Canada Highway. “I think it’s very easy, when you’re in a tough situation, to think that the safest thing is to do nothing,” she later said in an interview. “But there are a lot of situations in life where the choice not to act, which seems to be the neutral, safe one, is actually the most dangerous one.”

By the end of March, despite measures to limit its spread, COVID-19 had taken hold in communities around the country, tearing through long-term care homes and threatening to overwhelm hospitals. Health care professionals warned of a dire shortage of the personal protective equipment necessary to keep front-line workers safe, and they pleaded with the government to do more to procure surgical masks, N95 respirators, gowns, gloves, and face shields.

Internationally, the competition for PPE manufactured in China was intensifying as countries, Canada included, raced to build up their own supply networks. Dominic Barton, then Canada’s ambassador to China and formerly of McKinsey & Company, didn’t realize the gravity of the situation until Freeland called him up one day in early March. “She said, ‘Dom’—she never called me ‘ambassador,’ which I loved—‘we’ve got a massive problem right now. We don’t have PPE, there’s no supply chain.’” Barton recalls. “She said, ‘This is going to be the biggest management challenge you’ve ever dealt with—anything you did at McKinsey is chicken shit compared to this.’”

One of the items Canada desperately needed was reagent, a substance used in COVID-19 testing kits. “I said, ‘Well, I don’t even know what reagent is.’ And she goes, ‘Dom, you get it here by Friday, or people will die, you understand me?’ And then she hung up the phone.”

Over the next few days, Barton completely reorganized Canada’s missions in China and put a team of twenty-five together to map out potential PPE suppliers. One of the impediments to getting the medical supplies off the ground at Shanghai’s chaotic airport was that governments would swoop in with cash and take one another’s purchases right off the tarmac.

The maximum amount of money available to the embassy was $10,000, and any payments to vendors’ accounts took several days to arrive via wire transfer from Canada. Freeland, according to Barton, said, “Leave it with me.” Soon, the embassy managed to get $225 million in its account—more than four times the allowance of all of Canada’s diplomatic missions around the world combined—to process same-day payments to secure PPE.

A week after Freeland and Barton spoke, an Air Canada flight carrying the required reagent landed in Canada. In mid-April, planes began arriving with millions of masks and thousands of kilograms of reagent, as well as other critical emergency supplies. Over the next six months, Barton’s team would facilitate over 151 federally chartered cargo flights for Public Services and Procurement Canada.

“Freeland’s the one who grabbed me by the collar and said, ‘Get it done,’” Barton says. “I’ve never been tasked as directly, bluntly, but also inspiringly. She energized the whole place—it was like plugging my phone into the wall, I’d call her up and get another blast.”

Even before COVID-19 hit, Freeland was being referred to in the media as Trudeau’s “minister of everything.” It’s an honorific traditionally associated with C. D. Howe, who ran the William Lyon Mackenzie King government’s industrial war effort in the 1940s and was also in charge of transitioning the Canadian economy to peacetime after the Second World War. The pandemic highlighted Freeland’s ability to operate in the same kind of high-stakes and chaotic atmosphere. So it was not a shock to anyone that when Trudeau found himself embroiled in yet another ethics controversy, he turned to Freeland as part of the solution.

In summer 2020, the government awarded WE Charity a sole-source contract to administer a $900 million student grant program as part of COVID-19 relief. The opposition quickly highlighted the Trudeau family’s ties to the charity, noting the prime minister’s mother and brother had been paid for appearances at WE events. The controversy deepened when Canadaland revealed that two of then finance minister Bill Morneau’s family members were also connected to WE, one as a paid employee. Morneau later admitted to repaying $41,000 to the charity for expenses it had covered during family trips in 2017. Neither Trudeau nor Morneau had recused themselves from cabinet discussions about the contract, leading Pierre Poilievre, who was then Conservative finance critic, to call for Morneau’s resignation.

Amid reports of a strained relationship with Trudeau over economic recovery plans, Morneau resigned on August 17, citing the need for fresh leadership during a historic crisis. The next day, Trudeau named Freeland Canada’s finance minister—the first woman to ever hold the role. In addition to her deputy prime minister title, she would be tasked with shepherding Canada’s economy through its greatest crisis since the Second World War. She had achieved what her sister Natalka describes as a “huge” life goal. It was the post Freeland had wanted when she first entered politics, and she had “worked her way toward it.”

For the government’s first pandemic budget, “one of the things that the prime minister really wanted was something that would stimulate growth and create jobs—that was really the overarching theme,” says Vincent Garneau, then Freeland’s director of policy. For Freeland, that “something” quickly became a Canada-wide early learning and child care system. The Liberals had promised to create a national child care program in their 1993, 1997, 2000, and 2004 election campaigns. In 2005, Paul Martin’s government managed to sign deals for such a program with every province—but when Stephen Harper defeated Martin at the polls in early 2006, the Conservatives abandoned the agreements, opting instead to provide parents with direct subsidies.

With talk of a “she-cession,” as women disproportionately left the labour force to care for children out of school, Freeland saw child care as the best way to get women back to work and as a significant driver of long-term economic growth. “She really was the one that [advocated for] this idea of the child care system—she was not asked to do it by the prime minister,” says Garneau. Though it may have ruffled some feathers with cabinet colleagues whose responsibilities included child care and federal–provincial relations, she stepped in to personally oversee the implementation of the initiative.

On April 19, 2021, Freeland tabled the Liberal government’s first budget in more than two years. In a near-empty House of Commons, she announced that the government would be allocating $30 billion over the next five years, and $8.3 billion each year after that, to create a universal, affordable, and accessible child care system that would eventually cost parents an average of $10 a day, modelled off Quebec’s system of subsidized spaces. The federal government, according to the budget, would share the costs of the program fifty-fifty with the provinces and territories.

The opposition scoffed at Freeland’s pledge to deliver—then Conservative leader Erin O’Toole questioned whether the provinces would agree to a deal, and New Democratic Party leader Jagmeet Singh noted the Liberals had been promising a child care program for decades: “If they had any intention of doing it, it would already be done.”

But for Freeland, this was a personal ambition—and an intergenerational one. In law school, Freeland’s mother, Halyna, had only one child care solution: bringing her infant daughter to class. Later, Halyna fought for and got a town-run daycare in Peace River. “Chrystia had a lot of family support,” says Natalka. “She first had my mom, and then after my mom died, she had this rotating cast of my aunts coming through and basically taking care of her kids full time. I think it’s great that she had that, and I think it’s also great that society [does] things for women who don’t, because not everybody has aunts.”

Within a year of the 2021 budget, the federal government had reached an agreement on child care funding with every province and territory. “If you’d asked me in January 2021 whether she would get all provinces on [board], I’d say there’s no fucking chance [conservative Alberta premier] Jason Kenney is going to sign a deal with the federal government for frickin’ state-run child care,” says economist Kevin Milligan, who has advised the Liberals on various policies. But, he says, Freeland’s experience with dealing with the premiers during the pandemic “led her to believe that she could get this done across all the provinces. And she did.”

As finance minister, Freeland had no shortage of challenges to tackle: a ballooning deficit, post-pandemic inflation, a cost-of-living crisis, a housing shortage with homeownership becoming increasingly out of reach, and more.

But as the pandemic subsided, it left in its wake a country that, in many ways, felt more divided than ever before. In January 2022, a group of anti-government protesters calling itself the Freedom Convoy occupied the streets in front of Parliament Hill, demanding an end to COVID-19 restrictions and mandatory vaccinations and bringing downtown Ottawa to a standstill. After the government invoked the Emergencies Act and took action to freeze the bank accounts of key individuals involved in the blockades, Freeland, as finance minister, was the target of misogynist and threatening comments on social media.

The abuse wasn’t just online; in August, while waiting for an elevator in the reception area of an office building in Grande Prairie, Alberta, she was approached aggressively by a large man wearing jeans and a tank top. In a clip that went viral, the man could be heard yelling profanities at Freeland, calling her a “traitor” and demanding she leave the province.

More than ever, it seemed, Freeland’s philosophy of assuming positive intent in others was being tested. In November, she was accused of being out of touch after telling Global News that her family had cut its Disney+ subscription to save money. It was perhaps ironic that Freeland, whose frugality has been noted by university friends and political colleagues alike, would misread the prevailing public sentiment of the time, coming off as “smug,” “elitist,” “clueless,” and “entitled” instead of relatable to families struggling to make ends meet, according to emails sent to her office and obtained by the Canadian Press.

Over nearly a decade in power, the Trudeau government has suffered from the perception that fiscal issues are not a top priority, which made Freeland’s task harder. After each of Freeland’s budgets, pundits slammed the Liberals as fiscally irresponsible, pointing to ballooning spending and slow growth. Others don’t see cause for alarm, noting that Canada has the lowest deficit of all G7 countries. In addition, its “debt-to-GDP ratio is amongst the lowest of the industrialized world,” says economist Brett House. “So despite the fact that we had a couple of years of blowout budget deficits, we are still blessed with one of the best public balance sheets in the world. There is no question that we’re even close to looking at some sort of financial crisis, funding crisis, [or] credit rating downgrade.”

Economist Jim Stanford says that, without the benefit of hindsight, it’s impossible to put Freeland on a historical spectrum in terms of her performance as finance minister, given the “absolutely unprecedented circumstances that she was thrown into the middle of.” But he gives her credit for the way she confronted the economic devastation wrought by COVID-19.

In a way, he says, Freeland came into the role at the worst moment—no vaccines had been rolled out yet, and while Bill Morneau had quickly introduced the Canada Emergency Response Benefit and other income support measures, “a million questions” remained about “what comes next, and how long those supports would last.”

Stanford concludes: “We have to be concerned first and foremost with the well-being of Canadians, not with any arbitrary fiscal targets, or inflation targets, or any other traditional rules. This is something we’ve never experienced before, and our policy response to it has to be flexible and innovative, and I think she has done that.”

Making predictions in politics is a mug’s game, so only time will tell where Freeland will land next. Amid growing calls for Trudeau to resign as prime minister, hers wasn’t the only name that had been tossed around by pundits and pols as a potential contender for the Liberal leadership. Mark Carney, Mélanie Joly, and Anita Anand have all been spoken of as possible challengers. But given her position as Trudeau’s second in command, Freeland seemed to be his most obvious successor.

For a few months in 2022 and 2023, rumours swirled in the press about Freeland being a contender to be the next secretary general of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, or NATO. While unfounded, they speak to the heightened expectations around her next move and the sort of prominent positions in the international arena that she could credibly occupy.

Freeland is exceptional in that her record has been praised not only by many of her government colleagues and international counterparts but also by those across the aisle. “I would think she’s got to be pretty proud of her own work to date,” says O’Toole. “I’ve had some quibbles here and there, but I think she’s in it for the right reasons, and she has shown a real ability to represent the country.”

As one American former colleague notes, her journey from a tiny town in northern Alberta to the number-two position in Trudeau’s government is a “Chrystia story, but also a Canada story.”

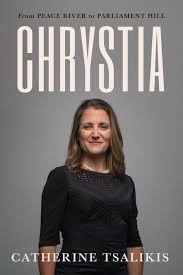

Adapted from Chrystia: From Peace River to Parliament Hill by Catherine Tsalikis, 2024, published by House of Anansi. Publication date: December 20, 2024. Reprinted with permission from the publisher.