She carries three names. The first, Sophia, is common. Its Christian meaning is “divine wisdom.” To Muslims, it means “beautiful.” Let’s think of her in these dignified terms. Her last name, Pooley, she took from the man she married in freedom. Pooley refers to a pond or a pool of water (from Old English pōl, from Dutch poel) that is located next to a ley—an area of pasture or grassland. It is her maiden name, her enslaved name, Burthen, that carries the most weight and casts the longest shadow.

Burthen is an archaic English word that will become burden. It now means a physical thing one carries or a psychological weight that can or will be passed on to others. But, originally, burthen was a very specific nautical term referring to a ship’s measure or capacity. That’s how it was used in the text of the following fugitive-slave advertisement: “Run away about 10 o’clock Thursday last from John Cannon, New York City, three Negroes with a sloop belonging to said Cannon, burthen about 35 tons.”

The term burthen has echoes in a ship’s berth—a place to moor a ship and unload its cargo. If it’s a living cargo, then the berth signifies both a landing where the next stage of the journey begins and the space within the ship where a person sleeps. Sophia carried this term as part of her name, as did her parents, Dinah and Oliver, and her sister. But where did this name come from? Who burdened them with a name pointing to a past filled with journeys in the holds of various vessels, in bondage? “Slaves rarely had a surname,” Charmaine Nelson tells me. Director of the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery at Halifax’s NSCAD University, Nelson is an expert in the long history of slavery in Canada and the country’s deep economic and social embeddedness in the slave trade over centuries. “If enslaved people did know their surname,” she continues, “it was likely that of their owner,” and this may be the source of Burthen, possibly the name of a past owner of Sophia’s ancestors.

How far distant in Sophia’s ancestry is the Middle Passage, which forced 12 to 15 million people across the Atlantic, of whom nearly 2 million perished—and were in effect murdered? Did previous generations of her family come directly to the coast of North America or did their journey happen in stages, via the Caribbean or South America? Or maybe with stopovers south of New York, around the Gulf of Mexico, Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia, Maryland, the shores of Chesapeake Bay? Do Burthen roots go back to the early 1600s, when the Dutch West India Company imported Africans to New Amsterdam (later renamed New York City), or to the first slave auction held there, in 1655?

Near the end of her life, in 1855, Sophia’s stories came into the possession of Benjamin Drew, a Bostonian who had come north under his claim that he “will endeavour to collect, with the view to placing their [his interviewees’] testimony on record, their experiences of actual workings of slavery.” An 1851 census lists her as seventy-five, putting her year of birth around 1775, at the beginning of the American Revolution. (She likely died in the 1850s or early 1860s.) In that 1851 census, Sophia appears as “Sophia Polly,” but even though Pooley has become Polly, it is obviously her, living in the Queen’s Bush settlement, Wellington County, Peel Township, Canada West (previously Upper Canada and now Ontario).

One can imagine Sophia’s name or at least a description of her existing elsewhere, and one can imagine the same for her parents and sister, who remain even more elusive. In her various owners’ business papers, for example. They’d be anonymous, numbers, listed as chattel, like furniture, equipment, or livestock. Or they’d each be described as a slave, a Negro(e), or with their true status hidden behind an apparently neutral term like servant. When a child, Sophia would be described as a girl; when a woman, a wench. If she had run away, we might find her in fugitive-slave advertisements. But the truth is that it was beneficial for enslavers to obscure the presence of the enslaved: they were taxable property, so many existed without a trace and do not appear in archives. This is especially true if, like Sophia, an enslaved person was born during the chaotic beginnings of a new nation that lacked an ordered bureaucracy.

Generations of white scholars and educators have used these absences to further erase and deny the existence of slavery in the northern “free” states and in Canada. They often try to dismiss slavery as something “common” to all human societies, as if the monumental scale and scope of the system that enslaved the Burthens has any true equal. They go further and claim that slavery outside of southern plantations was somehow more humane and that the enslaved were better off, as if there were a “nice” version of being owned and treated as disposable property. “Enslaved girls everywhere began laboring as young as four or five,” Margaret Washington states in Sojourner Truth’s America (2009), which meant they “had little opportunity for regular interaction with other black women, and endured a cultural isolation rarely experienced in the American South.” Maureen G. Elgersman Lee argues that, for enslaved women like Sophia, such isolation worsened their vulnerability by making it “impossible for many Black women to go to other Black women for respite from the degradation of physical or sexual abuse, for assistance in raising children, or for celebrating religious or labor holidays.”

Drew himself misses the true weight of Sophia’s unique narrative: she had not, as he declares, “fled from the North and the South into Upper Canada to escape the oppression exercised upon them by their native countrymen.” She did not come to Canada as a fugitive or free but as chattel. She traversed the foundations of the interconnected states of modern Canada and the United States that emerged from, and remain tethered to, empires of slavery and the systemic assault on Indigenous peoples and their lands. Enslaved children knew their status. They worked from as young as four years old, were hired out and traded. They were punished and constantly exposed to loss, trauma, and violence, as were their parents. In Dutchess County, New York, where Sophia was born, “the threat of sale was a source of constant anxiety; actual separation produced gut-wrenching anguish.”

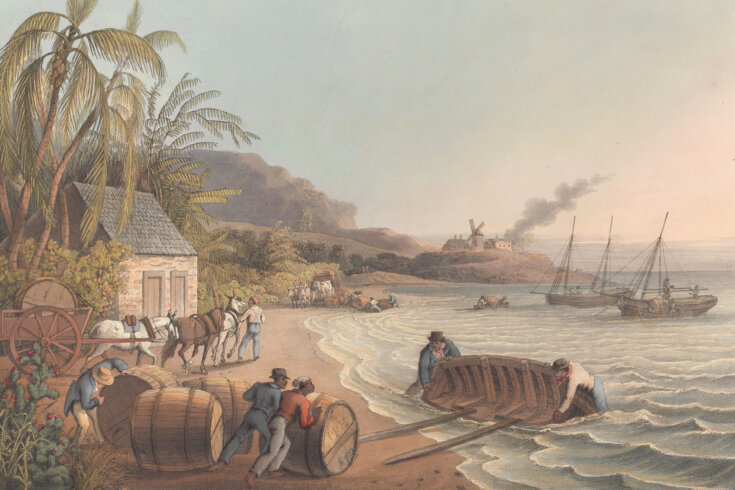

That this woman was enslaved in Canada, however, would prove to be a revelation for future generations—for us, now, who believe the well-burnished myths of the Underground Railroad and that the country’s history is free of the legacies of slavery and systemic racism. Canada was, in fact, both focus and platform for the European colonial enterprise. “For over 200 years,” prior to Confederation, in 1867, “New France and British North American colonies held Africans in bondage and Canadians helped suppress Caribbean slave rebellions,” Yves Engler reminds us in Canada in Africa: 300 Years of Aid and Exploitation (2015). He quotes Natasha L. Henry from her book Emancipation Day: Celebrating Freedom in Canada (2010): “Very few Canadians are aware that at one time their nation’s economy was firmly linked to African slavery through the building and sale of slave ships, the sale and purchase of slaves to and from the Caribbean and the exchange of timber, cod, and other food items from the Maritimes for West-Indian slave-produced goods.” To borrow from Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s description of European practices in Africa, Canada too has been fertile ground for “planting European memory,” narratives that nurture the selective erasure of the past and justify the nation’s continuing participation in the business of natural-resource extraction and in the dismemberment of communities.

Sophia Burthen (Pooley) embodies this erasure. To follow her is to follow the ley lines she traced and crossed, which expose the realities of the transatlantic slave trade as the bedrock of the British Empire and hence of Canada. The much-vaunted United Empire Loyalists brought enslaved people here. Caribbean-based enslavers used their “compensation” to acquire land and fund new businesses in Canada. The source of materials and trade feeding industry in Canada (sugar and cotton coming in; furs, fish, timber, liquor, and cloth going out) were products of slavery. Sugar barons and lumber merchants in Montreal, shipbuilders in the Maritimes, leaders of industry in Upper Canada / Canada West, the first banks—they all accumulated vast wealth from the slave economy. Post-Confederation, their tainted wealth flowed into the infrastructure of a modernizing Canada. It lingers in the assets of leading banks that for years refused to give mortgages to nonwhite citizens. As Engler explains, “Much of the capital used to establish the current incarnation of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) came from supplying the Caribbean slave colonies.”

Sophia did not find freedom at the terminus of the Underground Railroad, that epic journey Canada claims as a foundational narrative and has nurtured to distinguish it from neighbours south of the border. Sophia was sold to a property owner named Samuel Hatt, who paid $100 for her, and she “lived with him seven years” in Dundas, Hamilton, before presumably heading west, into Waterloo Township and eventually to the free Black settlement of Queen’s Bush. How many Black bodies, “servants” and “labourers” skilled in the building of roads and mills, toiled on behalf of the Hatts? The names of those who enslaved people are inscribed on this landscape, on the signs for streets, towns, and buildings. Many came north from New York. They had roots, like Sophia, along the Hudson River, in Dutchess and Ulster Counties and at Albany. And what of those who owned the Burthens, who stole and sold them? They came here too. Their names are also spelled out on signs and heritage plaques, while Sophia’s lies buried, her sister’s erased, in shadow, here.

Adapted from It Was Dark There All the Time: Sophia Burthen and the Legacy of Slavery in Canada. © 2022 by Andrew Hunter. Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions.