Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

Following a bout of pneumonia in 2014, Becky Hollingsworth experienced a persistent cough and shortness of breath. Her doctor diagnosed asthma and prescribed two inhalers plus an oral medication. They eased her cough, but Hollingsworth wasn’t convinced that asthma was what she had. Her symptoms weren’t severe enough, she thought. So, months later, when she received an automated phone call inviting her into an asthma study, she leaped at the opportunity.

The study was led by Shawn Aaron, chief of respirology at the University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital. His research was inspired by what he was seeing among patients referred to him because their asthma medications weren’t working. Asthma is a common disease of the airways that comes with symptoms, such as wheezing and chest tightness, also seen in other lung conditions. But, when Aaron tested the referred patients, he found many for whom the diagnosis was simply wrong. He’d already done several smaller studies; this new project was ambitious, involving 613 adults in ten locations across the country.

Hollingsworth, a retired nurse, was an eager recruit, willing to undergo repeated tests in Ottawa, an hour-long drive from her home. The first test was spirometry, one she’d not had before. Wearing nose clips, patients exhale into a tube connected to a spirometer, a device that measures airflow, as fast and hard as they can for five seconds. After three blows, they inhale a bronchodilator—medication that relaxes muscles around the airways—wait fifteen minutes, and do three more blows. If the machine registers improvement in airflow, the diagnosis is asthma.

In Hollingsworth’s case, the bronchodilator made no difference, indicating she might not have the disease. But asthma symptoms can come and go. On a good day, a patient can do well on spirometry but still have the condition. Aaron therefore submitted all study participants who appeared asthma-free to a second test: the methacholine challenge. Methacholine is a chemical that causes the airways to get twitchy and irritable. During the test, patients inhale increasing doses of methacholine and blow into a spirometer after each increase. A person with asthma will react badly and be hyper-responsive to low doses of the chemical.

In day-to-day practice, it’s too costly to give everyone who passes a spirometry test the methacholine challenge; it is typically reserved for the most difficult cases. But Aaron needed to be precise in determining how many in the study had received incorrect diagnoses. For even greater certainty, he instructed participants who passed the methacholine challenge to wean off their medications over several weeks and then get retested. Those who consistently showed no indication of asthma were then assessed by a pulmonologist to determine what they actually had.

The results ruled out asthma in nearly a third of the participants—203 in total. Sixty-one had no symptoms at all, and almost as many had only allergies. Among the others, some suffered anxiety, others gastrointestinal reflux disease. Several had serious conditions that had been missed, such as cardiorespiratory disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder. Hollingsworth had a post-viral cough linked to her previous pneumonia. She never did, and still does not, have asthma.

Conclusions from the study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2017, were consistent with earlier research in Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden. Aaron’s study is the largest to date, and it demonstrates that many patients can safely withdraw from treatment.

There are reasons for the high rate of misdiagnosis. Asthma is a variable disease and can go into spontaneous remission. If people never get retested, they may assume they still have asthma. But the bigger reason is systemic. Aaron asked each study participant’s doctor to complete a questionnaire and medical-record review and provide evidence of spirometry, methacholine challenge, or other objective tests employed in making the original diagnosis. Of the 530 physicians who responded, only half had requested any such tests. The others had made the diagnosis subjectively, on the basis of symptoms observed in an office examination.

It would be unthinkable to diagnose diabetes without ordering a blood test or to prescribe blood-pressure medication without wrapping a cuff around a patient’s arm to measure it. Yet many family physicians don’t order the standard test for asthma, which has resulted in a staggering number of Canadians—785,000, according to one estimate Aaron helped tally—being treated for a disease they do not have.

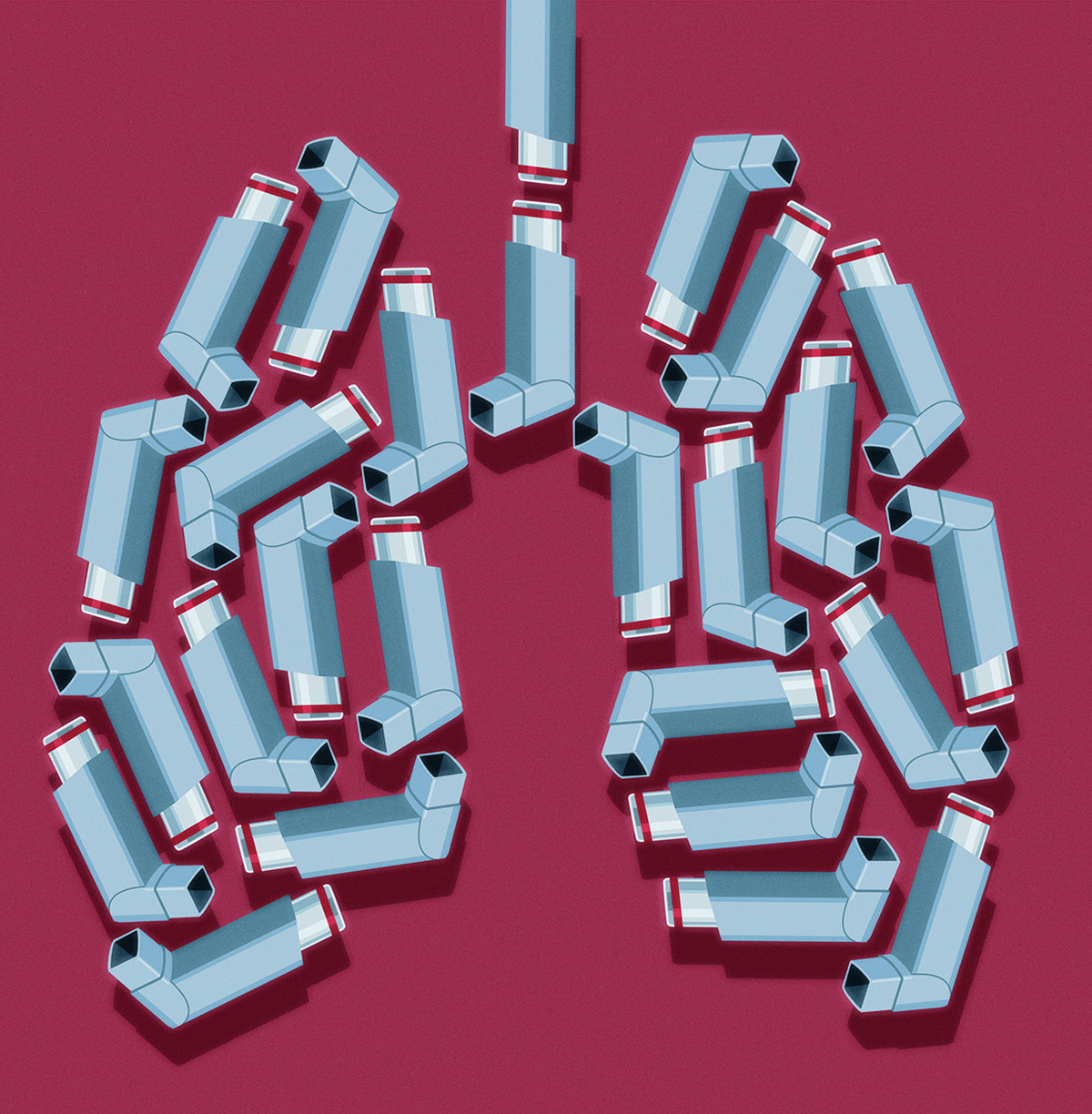

When it comes to diagnosing asthma, getting it wrong is not a trivial matter. Being labelled with a chronic illness can have psychological effects and hold people back from physical activity. Drugs have side effects, inhalers included. Typically, people with asthma use a corticosteroid inhaler daily and an emergency bronchodilator—such as the familiar blue puffer, Ventolin—if they have an attack. Prolonged use of steroids is associated with osteoporosis, earlier cataract formation, glaucoma, easy bruising, and skin thinning. Then there’s the price tag. For Canadians, the yearly cost of medication can be in the hundreds of dollars. A University of British Columbia study, published in BMJ Open in 2019, calculated the overall health care burden, including hospital and physician visits and drug expenditures, of patients who had received asthma misdiagnoses in Canada. It came to $242 million per year. And the harm of missing a serious illness due to lack of a proper test is incalculable.

Specialists have long argued that family physicians should not diagnose asthma without first ordering spirometry. Some general practitioners will administer the test in their own offices, but most find it impractical because, for starters, the fees involved aren’t enough to cover the effort. In Ontario, the provincial health plan pays physicians $24 to perform spirometry; British Columbia pays $28; Saskatchewan, $50. Some provinces, including Quebec, pay no fee at all. A high-quality, well-interpreted test takes time. Patients need coaching to do the test properly; the machine spits out results, but they are meaningless if the physician is not experienced at decoding them. Clare Ramsey is an assistant professor of respirology and critical care at the University of Manitoba. When she gets a referral, the first thing she does is make sure the patient really has asthma. She sees some who’ve never had spirometry; others have had spirometry that “in no way looks like asthma” but led to a misdiagnosis because of poor interpretation.

The better option than conducting their own spirometry is for doctors to refer patients to labs that measure lung function, but Ramsey acknowledges that there are waiting lists. The labs that do spirometry are most often in specialized centres or hospitals, where appointments aren’t easy to get. At Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre, for example, it can take six months to get a test. It’s a problem that exists across the country. When a patient has trouble breathing and it looks like asthma, it’s expedient to offer medication and say, “Let’s try this and see if it helps.” Yet medication may improve breathing even if the patient doesn’t have asthma, so if a doctor doesn’t follow up with spirometry to confirm, the patient could be one of the thousands who end up living with the wrong diagnosis.

Access to objective tests for asthma remains a huge problem across the country.

Rhonda Gould knows the frustration of waiting. She is a fifty-eight-year-old certified dental assistant living in North Vancouver who developed a lung infection last spring, just as COVID-19 erupted in Canada. Her COVID-19 test was negative, and her infection was treated, but she was left with an annoying worsening cough. By June, she was experiencing difficulty breathing. A spirometry test did not indicate asthma, but her respirologist suggested she try inhalers, hoping they would provide some relief. She needed a methacholine challenge test, but due to the pandemic, pulmonary-function labs were severely restricted in what they could do. She would have to wait.

The breathing attacks continued through the summer, and in September, Gould’s family doctor, suspecting that her condition was triggered by fumes from the aggressive use of disinfectant wipes in the clinic where she worked, recommended she transfer to office duties. Her breathing improved, but on November 18, she was needed back in the clinic. By the end of the day, she could not get a breath and was panicking. “It was the scariest thing of my life,” she recalls. “I felt like I was choking.” That evening, she made a desperate call to her respirologist, who helped her calm down as she took puffs from her steroid inhaler. He told her to stay away from the wipes. Then he sent a referral to Chris Carlsten, head of respiratory medicine and director of the occupational lung disease clinic at the University of British Columbia.

Finally, this January, Gould had a second spirometry test, followed two weeks later by a methacholine challenge, which confirmed the absence of asthma. Her respirologist also did a scope of her lungs and noted that her vocal cords were erratic and twitchy. After reviewing the complete file, Carlsten concluded that she likely had an irritable larynx syndrome that could explain her reaction to the sanitation wipes. He recommended speech therapy to strengthen the muscles around her vocal cords. Gould was off work for months. Circumstances related to the pandemic, not lack of good care, delayed the testing she needed. Nevertheless, it’s a lesson in the importance of confirming diagnoses.

To see what improved spirometry access can look like, we have the example of the Vancouver area, where, several years ago, seventeen hospitals agreed to use the same referral form, making it easier for patients to book appointments and choose the lung-function lab most convenient for them. There is also a special clinic attached to Vancouver General Hospital where anyone with a doctor’s requisition can walk in and get a spirometry test. In 2019, prepandemic, the clinic reportedly saw 4,000 walk-ins. But access remains a huge problem elsewhere in the province—and the country.

“We know that the need for spirometry is massive compared to what’s actually being done,” says Carlsten, who is also the director of Legacy for Airway Health, a new organization dedicated to the prevention and care of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He has tried for many years to educate family physicians about the importance of objective tests for asthma and agrees with Shawn Aaron that getting a spirometry test should be as easy as getting an X-ray for a broken bone. But it will take a cultural shift. Spirometry is, quite simply, undervalued. While Carlsten firmly believes that, if more labs offer spirometry, more family doctors will request it, efforts may be better directed at educating the public so that patients know to demand the test.

“Doctors and administrators love to set up tests that are going to bring in a lot of money, either into the doctor’s pocket or the hospital’s coffers,” Carlsten says, “and this is not a big money maker.”