Sometime in my mid-to-late twenties, less than a decade after I’d been diagnosed bipolar II, I participated in a study that sought to glean insights from “high-functioning” bipolar people—presumably to figure out why we were high functioning and if anything we had to share could help others become high functioning too.

The study took place in a little room in a low-slung building that seemed like it had been built in the seventies. The woman who administered the study was a grad student, maybe a bit younger than me. She proceeded to ask me questions about my diagnosis and mental health history. When she got to the part of the survey about hallucinations, she seemed apologetic, ready to skip it—bipolar people can but don’t always experience hallucinations and/or psychosis, and it’s less common with bipolar II than with bipolar I. “Oh,” I said, “we will need to go through those.”

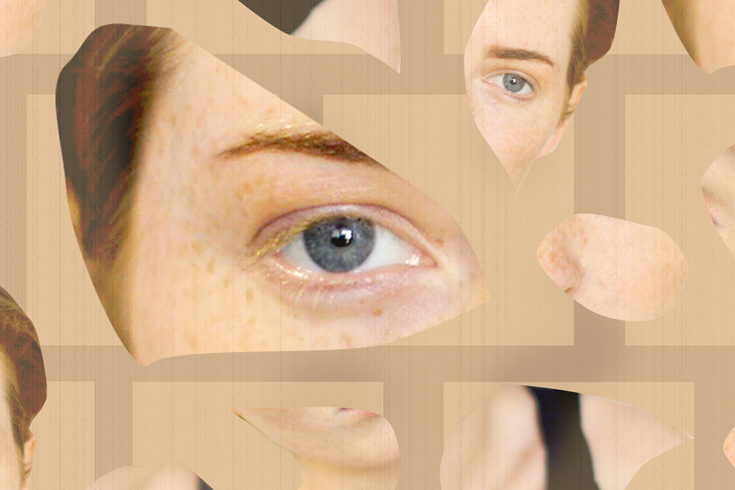

After I answered that, yes, I’d experienced visual hallucinations while ill and, yes, I’d experienced auditory hallucinations while ill, she excused herself and went to consult, a second time, with the older psychologist. When she came back, I could tell that I had gone from being one type of person, in her perception, to another type of person. The wrong type of person. The type of person we place in a separate category in order to quarantine whatever it is that makes them abnormal and a bit frightening. (I’m using abnormal here colloquially—but also because “abnormal psychology” is the branch of psychology that studies mental disorders, of which I have several.)

The period of time in which I was hallucinating, I was also living in circumstances that the woman who was interviewing me probably would have found appalling. In the winter, my then partner and I wore toques and hoodies to bed because it was too cold not to; at the very end of my bachelor’s degree, which coincided with the peak of one of his binges, I woke up to write my final exam and had to walk over him, as he was passed out on the floor and surrounded by broken glass, to get to the coffee maker. I was taking lithium. I saw birds in the corners of our rooms—one owl, in particular, recurred. I heard a low, echoing voice. I knew these things were hallucinations, and for the time I experienced them, I lived with them just like I lived with my then boyfriend’s alcoholism and the broken glass on the floor.

Many years later, now that I am stable and my life is stable, I can sometimes still be picked out by normal people, ones who can sense that I’ve experienced periods of poverty and illness. Other times, I can pass for the type of person that has never experienced these things—and then, if they come up, they come as a shock. I’m not sure what’s better or worse.

When I think about mental illness, I think first about Virginia Woolf placing her hand into a pocket of rocks. I think about movies or shows I’ve seen where depression is depicted as a series of long, slow-moving days, stuck in one’s apartment or home, maybe breaking the monotony by heading to the corner store in a bathrobe in search of cigarettes and ice cream. (When I think about mania, I think about rich young men taking cocaine and driving fast and apparently covetably ugly small cars.)

Only after a few beats do I think about myself—my life oriented around working through illness, an economic crisis never too far off. Perhaps this anxiety is protective; perhaps I’ve never been so badly off, maybe all those mornings I’ve shoved my legs off the side of the bed to propel my body out of it wouldn’t have been possible if I was more ill, truly ill. Depictions of serious mental illness seem to exist without a middle—celebrities whose lows are captured by paparazzi and men with shopping carts under bridges. Most of our breakdowns are private, and if we talk about them at all, we talk about them after we’ve stabilized. If you’re not stable, people talk about you, for you, instead.

Bipolar disorder has been romanticized in pop culture. It’s presented as better, perhaps more inherently interesting, than depression, which we see as a disease that renders already waifish young women thinner and sadder or middle-aged men more bloated and full of beer and ice cream. Like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder is generally embodied onscreen by men—though it affects women at more or less the same rates.

Bipolar disorder is depicted as a font of creativity, fun, and terrible choices. Virginia Woolf, Vincent van Gogh, Stephen Fry, Carrie Fisher, Charlie Sheen, Britney Spears, Chris Brown, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Lou Reed, Kim Novak, Edvard Munch, Marilyn Monroe: if you’re famous and bipolar, your name will begin to grace googleable lists, many devoid of any kind of context. You can be known for succeeding despite your diagnosis or you can be known for the train wreck you make of your life and career. The only way you can stake a claim on your own story is to tell it yourself, like Fry did.

The problem with sharing one’s personal story—or the story of being bipolar filtered through one’s experience—is that the segment of your audience that doesn’t share the diagnosis runs the risk of essentializing your disorder, placing your experience at the pinnacle of their pyramid of understanding of what it means, in general, to be bipolar. And the further problem is that it’s easiest to package one’s illness in the way that it is already culturally understood—and maybe the cultural understanding even begins to shape your understanding of yourself.

The end result is that the story of being bipolar—an illness with ups and downs, which offers a narrative more easily than illnesses without—is one where, often, the manic protagonist must wrestle his euphoria to the ground for the sake of his better sanity. When you are manic, the understanding is that you enjoy your mania. It’s only the mess, afterward, that provokes reflection and a tidy combination of SSRIs and mood stabilizers.

This experience of mania has not been my experience of mania. Or maybe it has been and I just like it less. The broad truth about suicidality and bipolar disorder is that people with it are about thirty times more likely than the general public is, and twice as likely as people with unipolar depression are, to kill themselves. The broad truth about me is that I never want to die, and that if I did kill myself, it would happen accidentally, while hypomanic.

Adjacent to the list of famous people with bipolar disorder that I can recite if asked is another list, a list of nonfamous people, friends and acquaintances. I won’t list them—they’re not famous, and their stories are not mine to tell. Two of them died by overdose, one accidentally and one not as accidentally. Both were people who maybe found it easier to care deeply about others than about themselves. When I’m up late at night, wanting to sleep but pushing sleep off because I am afraid of death, one or the other will come floating to the top of my mind, and I will think, Shit. Shit because I don’t want either of them to be dead. And I don’t want to die, either. Not ever and definitely not accidentally. The night that I was briefly hospitalized—the night that was a culmination of terrible days and weeks, the night that led to my diagnosis—is a blur with pinpricks of clarity. But I remember very acutely the feeling that led me to down, by shots and then all at once, an entire bottle of whisky alongside what remained of my Ativan prescription—like I had, sometime earlier, swallowed firecrackers and would give anything, do anything, to put them out.

I don’t associate mania with creativity, or fun, or clarity; I associate it with an abundance of energy that seems like it needs no fuel but that will end up using me for its fuel. When it comes now, I treat it as if I live on a cottage by the ocean and a storm is about to come through. I don’t think that my experience of bipolar disorder should be read as bipolar’s new textbook definition, but I do wonder why I feel such a chasm between the way that the illness is so often depicted and my experience of it. I wonder if there is something about me that is lacking, essentially unfun, as dull and bland as baby cereal. Or if, when I am asked to help explain why I am “high functioning” and other people are not, the answer is fear. Fear of poverty and fear of dying. Can fear keep you safe? Will fear kill me early, just in a different way?

Esme Weijun Wang writes very movingly about being one of the good sick. Her doctors are initially reluctant to switch her diagnosis from bipolar disorder to schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, because schizoaffective disorder “has a gloomier prognosis and stigma than bipolar disorder does.” During an earlier hospitalization, Wang noticed that there was even a hierarchy on the ward: the two women at the bottom of the hierarchy were the woman who were very clearly, to the other patients, schizophrenic. Wang, who had not yet experienced psychosis, treated schizophrenic Pauline “like a contagion.” Perhaps, she writes, she sensed the possibility of psychosis “thrumming in [herself] even then.”

There are many benefits that one gets, being the good sick. And there are compromises one makes to remain the good sick. And then there is the fear of becoming the contagion.

I’ve been asked several times why I chose not to come out as nonbinary to my OB-GYN and the other medical professionals I interacted with when I was pregnant. There is the simple answer, which is that I didn’t have alternative options for what, other than “mother,” I could call myself, and I didn’t know if I could find trans-affirming care. On the flip side, I had a very strong urge to be as candid as possible about being bipolar so that I could be streamed into emergency mental health care if it became necessary. While being candid, though, I also wanted to appear as stable, as normal, as possible. I needed to begin as one of the good sick so that, if I became, over the course of my pregnancy or after birth, one of the bad sick, I would have the best chance of accessing the kind of care that might save me. To be the good sick, it helps to be articulate, to make the right kind of eye contact, to check off as many privileges as you can. I did not know if I could afford to be nonbinary and bipolar. I compromised.

When you are the bad sick, you become a cautionary tale. My great aunt is a cautionary tale. She was first bipolar and then got dementia and then, most recently, cancer. I don’t know my great aunt except through photos; she was the youngest of three sisters and very outgoing in her youth, but by the time I was growing up, she didn’t like to leave her apartment. I learned she had cancer when my cousin posted about it on Facebook. My cousin wrote first that she was upset to have unexpectedly learned of her aunt’s illness and then, two days later, that “every disease is mental first” and “everything is mind over matter” and “everything is about vibration.” I wondered at what stage my cousin thought that my great aunt should have vibrated herself out of illness. I thought a series of angrier things.

As with my initial desire to distance myself from my great aunt’s illnesses, I don’t feel proud of the compromises I’ve made to try to be and to appear one of the good sick. But I’m sure that, if I was faced with the same choices at the same points in my life, I’d make the same decisions over again. I do worry that we understand illness as something that we hold and foster as individuals, and that this masks the extent to which social conditions, like racism, sexism, homophobia, overwork, and eviscerated social safety nets, trigger and exacerbate it. This is the dark side of gleaning what we can from the narratives of the good sick in order to give better “tools” to the bad sick—Is the idea to improve someone’s quality of life or to render them a better worker? It’s also why I tap out, each year, of participating in campaigns like Bell Let’s Talk Day: they place the onus on the unwell to share their stories for nickels and dimes while raising brand recognition for a major corporation. Understandably, people share what is safe for them to share; I doubt Bell will chip in on my mortgage if I no longer appear quite as employable because I regularly saw an imaginary owl for a period in my early twenties. The result is a sanitized portrayal of illness that does little to shorten psychiatric wait times for people, like me, who rely on provincial health care to seek mental health treatment.

Sometimes, I dream about how wealthy I would need to be to take a break from feeling the fear that propels me to remain stable. I don’t dream about not being bipolar, because I don’t know where my self ends and where the illness begins—and if there is even really a difference. And I don’t know what I would dream to render the divisions between good sick and bad sick unnecessary, to make it so that we all get to remain people, without sacrificing some of us to quarantine and cautionary tale.

“On Being Bipolar” is adapted from the essay collection Like a Boy but Not a Boy by andrea bennett (published by Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020). Excerpted with permission from the publisher.