The Greyhound terminal in Saskatoon is a small desk in a corner of the Husky station near the airport. It is surrounded by bright displays of trucking paraphernalia, shelves of jerry cans, and rows of replacement windshield wipers. I arrive at seven in the morning on October 30 and find my eastbound bus already there, idling in the dark. A few other passengers shuffle around, yawning and furtively checking their phones. When we finally embark, a little after eight, we are seen out by a chorus of melancholy farewells from the terminal staff. Several of them will be out of work as of the next day.

Last July, Greyhound announced that it would end all bus service in Canada west of Ontario as of October 31, 2018, the only exception being one route between Seattle and Vancouver. The decision was blamed mostly on low ridership and high overhead costs. For nearly a century, buses have been an important transportation lifeline for people in many small western towns, and when the decision was announced, some were worried that it would effectively isolate these communities from the rest of the country.

Our driver, Joe, has been with the company for fifteen years. As we get underway, he gives a cheerful, polished safety talk over the PA. I wonder how many times he has delivered the same speech. Joe will be let go from Greyhound as of tomorrow too.

The place names on my itinerary read like accidental poetry. Elstow, Colonsay, Plunkett, Foam Lake, Insinger, Minnedosa—pioneer surnames and plain-spoken settler descriptions punctuated by Indigenous terms, filtered and distorted through generations of colonists.

The view beyond the window is a mottled blur of browns and greens, like military camouflage come to life. My city-trained eyes struggle to make sense of it all, and I find myself in a landscape-induced fugue state. Details begin to resolve from the relentless, side-scrolling scenery, though. Haystacks, hydro wires, grain elevators. Ponds and trucks and tanker cars resting at railroad sidings.

At our stop in Yorkton, Joe is replaced with Darren, another driver, who arrives in a vintage grey uniform. He reminds me of John Candy—cheery but wistful.

Buses are cheaper than air travel, more direct than the train. Taking them can be easier and safer than driving your own vehicle. One particularly passionate advocate affirms that what she loves best is the connection she feels to the terrain when travelling at ground level. “You can’t see the land from the air!” she insists. I watch the prairie undulate around us, rumpled and furrowed, wet and alive. She’s right.

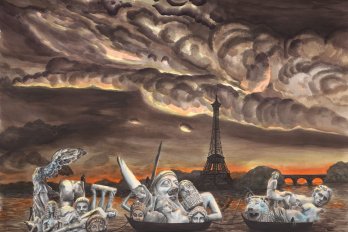

As the day wears on, the windows grow more and more dusty, and the view outside becomes increasingly impressionistic. We cross the border into Manitoba, and the prairie sky changes from bright blue to a bruised, angry yellow green to featureless grey in less than an hour. The landscape transforms, too, from flat tableland to rolling foothills. We enter Riding Mountain National Park, high atop the Manitoba escarpment, and as the light begins to dim, a bright, clear ribbon appears at the western horizon—a fierce sliver of sunset, flickering through gaps in the low cloud cover. It eventually fades away.

We roll into Brandon in darkness. The terminal is empty save for some plastic seats and a vending machine. I am the only passenger getting off. The ceiling lights cast an aggressive, sodium-vapour glow over everything, like an old, sepia-toned photo that wasn’t processed properly. The place feels like a memory already.