Founded by Jesuits in 1554 on a vast, fertile plateau near the Atlantic coast, São Paulo has historically drawn large numbers of opportunity seekers. In the nineteenth century, Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, and Germans came to run its vast coffee plantations. Then, when the coffee economy began to decline in the early twentieth century, the newly industrializing city drew waves of immigrants from Japan, the Middle East, and northeastern Brazil. By 1940, São Paulo was considered Brazil’s economic engine, with a population that had increased by a factor of thirty, to almost 1.3 million, in just under six decades.

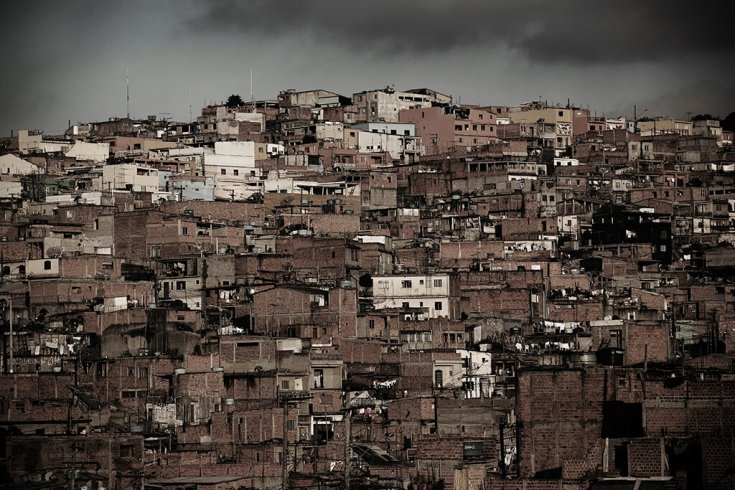

Another seven decades on, the figure is 11 million. Rapid growth has combined with the consequences of poor urban planning, military rule, and municipal corruption to cause deep instability. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme estimates that a third of the city’s inhabitants now live below the poverty line, and as the city’s economy begins to shift again — this time toward the service and technology sectors — São Paulo’s lower classes find themselves increasingly marginalized, taking refuge in ever more drastic living situations.

Some stay close to the centre, creating vertical slums in the thousands of abandoned buildings scattered throughout the city core, while more than two thirds of the populace lives in favelas on the outskirts, facing appalling sanitary conditions, overcrowded schools, and rampant crime.

A Downtown Squatters’ Movement

On November 3, 2002, the Homeless Movement of Central São Paul (MSTC) helped 468 families occupy an abandoned clothes factory downtown. The twenty-two-storey Prestes Maia 911 building had been empty for seventeen years, serving as a hub for drug dealing and prostitution.

For four and a half years, inhabitants lived side by side in tiny apartments, lacking basic facilities and privacy. Communal problems tended to affect everyone, and though democratic procedures were put in place to deal with them, domestic violence, alcoholism, and theft were common. Police frequently threatened occupants with eviction, sometimes prompting demonstrations.

São Paulo’s government finally signed an agreement with the residents in February 2007, ending the occupation. Some were moved to communal projects on the city’s fringes, while most received rent assistance so they could find homes downtown.

Samara and Mauricio

Samara, thirty-one has lived most of her life on city streets. At the time of the Prestes Maia occupation, she and her daughter, Sara (born as a result of rape when Samara was twenty-five) had been sleeping on the street blocks away from the building. One of the MSTC‘s leaders found her and brought her in. There, she met Mauricio and had a second child.

By Samara’s third year in the building, the couple had lived on three different floors. Mauricio was often away, working long hours for a fast-food chain in the business district. Their relationship began to deteriorate, with Mauricio sometimes abusing Samara.

The settlement with the city eventually offered some relief. Mauricio moved the family into an apartment downtown, and Samara found an employer who provided free daycare. Sara was able to start attending school.

Life on the Edge

Opportunities for change are just as limited in São Paulo’s outer slums. What few routes for advancement exist are often dimly understood or difficult to pursue. Schools overflow to such an extent that in some areas children attend classes in four-hour shifts. The best jobs, meanwhile, require a long commute to the city centre.

As a result, youths tend to get trapped in destructive patterns. Jacqueline, shown below, became pregnant as a teenager. She bore the child, but eventually left it with the father and married another man.

Twenty-five-year-old Zé Foguete, also shown below, was abandoned by his mother when he was younger. He was heavily involved in crime for a time, but left that life after seeing many of his friends murdered. He now works in the community but, like many young adults on the outskirts, abuses cocaine and other drugs.

Dona Fia, a woman in her late sixties, fled an abusive husband and sibling three decades ago, bringing her seven children from the country’s interior to São Paulo’s eastern periphery. Upon arrival, she remarried and had three more children. Her second husband eventually left, but before he did the couple built a small house on a good-sized plot she has since sold off to neighbours.

One of her sons, Donizete, developed a severe drinking problem in his mid-thirties.

This photo essay first appeared in the May 2008 issue of the Walrus