Montreal is one of the North American capitals of prostitution and Internet pornography. Once confined to flophouses around St. Catherine and the Main, brothels today are more likely to be apartments in middle-class neighbourhoods and five-star hotels. Luxury escorts can command $500 an hour, but a flourishing Internet marketplace provides a wide array of prices. Prostitution is a growth industry, offering attractive part-time work to university students looking to pay their tuition, and young professionals keen on topping up their starter salaries. Spinoffs include a thriving web porn industry, sex tourism, and an explosion in cosmetic surgery fuelled by women in the trade, and others for whom looking like a top model is deemed worth the price and pain. In a thoroughly sexualized culture, advertising, film, and television set the tone. Whether the body itself is on offer or merely part of the package, young women are increasingly driven to emulate an image of beauty presented by the media. Smooth, clear, wrinkle- and cellulite-free skin is fast becoming the Western world’s burka, a social imperative masking signs of age, imperfection, and even personality.

If all this sounds like the voice-over for a steamy documentary long on lap dancers and short on hard-core statistics, please note: these views are held by a woman who earned a master’s degree in literature with a thesis on Daniel Paul Schreber, the German jurist whose Memoirs of My Nervous Illness, published at the turn of the past century, was hailed by Freud and Lacan as a pioneering work of sexual psychology. At thirty-three, her novels, published in France by Éditions du Seuil, have won important literary awards, generated considerable buzz in academe, and enjoy sales in the hundreds of thousands. Her views on the state of sex in Quebec are, however, based on primary sources. As a student at the Université du Québec à Montréal (uqam) in the late 1990s, Nelly Arcan worked for a high-priced escort agency, an experience she drew on for her debut novel, Putain, published in New York by Grove Press in 2004 as Whore.

“It’s perfectly normal for a writer my age to write about sex,” Arcan says, responding to criticism that her work is limited by fixation on a single subject. “We live in a world obsessed by sex. There are no taboos acting as restraints. Women are conditioned by the profusion of images in advertising created to arouse desire. Obviously, sex is a source of power.”

Arcan’s first two novels are mesmerizing monologues, stream-of-consciousness outpourings as told to a therapist (Putain) and an ex-lover (Folle), implying strong identification between narrator and author. The publication of À ciel ouvert last fall revealed that she’s also a first-rate storyteller. Set in the recognizable café and condo scene of the Plateau Mont-Royal, her third novel is a taut, briskly paced thriller about two women engaged in mortal combat over the same man, a fashion photographer whose libido feeds on Internet porn. Whereas the earlier novels were anti-cathartic spirals into death, her latest is classical in structure, arriving at a jaw-dropping yet perversely believable ending.

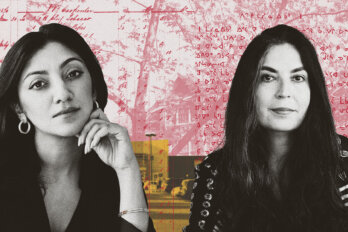

Both a juicy page-turner and an unsettling report from a social frontier, À ciel ouvert marks Arcan as the front-runner in a generation of accomplished young female writers for whom sex is primary material, a currency, a language, a playing field on which the rules are changing fast. Marie-Sissi Labrèche, Heather O’Neill, Marie Hélène Poitras, Irina Egli — like Arcan, they’re beautiful, well educated, and keenly aware of how valuable this combination of assets is in the international marketplace of literature.

A petite, soft-spoken blonde with unnaturally puffy lips and Owl of Minerva grey eyes, Arcan cultivates a complex public persona. Riding the promotional circuit for À ciel ouvert, she complained that the media couldn’t get beyond her Putain past, that sex is only matière and what counts on the page are words and ideas. Yet her weekly column in the giveaway tabloid Ici deals almost exclusively in anecdotes about dildos, condoms, body parts, and trysts — raunchy slices of thirty-something life. Invited to appear on a popular TV talk show, she wore a gown offering a generous view of her famous surgically enhanced breasts, and was mortified when the male hosts refused to take her seriously.

Dressed in a thick grey sweater, hair tucked up under a cap, Arcan doesn’t stand out in the crowd at Café aux Deux Marie. I stand at the bar for a good ten minutes, keeping an eye on the door. When we finally connect, she flashes a faintly nervous smile, as if relieved to be rescued from the isolation of sitting alone. When I tell her I think she’s an awesomely good writer, she’s surprised. Slow to relax into the subject, she seems strangely removed from her writer self, as if the ability to dissect a character’s psyche in fiercely confident prose were no greater feat than tossing off a newspaper column. She wears her beauty uncomfortably, like someone who has overdressed for the occasion and can’t stop worrying about it. I catch myself wondering what the signals would be like if I were a man.

After an excruciating affair with a French journalist (see Folle), she has been with the same guy for more than two years, a German eight years her junior who lives in Frankfurt and works in public relations. They spend a few weeks together whenever possible. At her insistence, he hasn’t read any of her novels, nor have her parents. “I exposed some very deep wounds in my writing,” she sighs. “I don’t want people close to me to know all that.” Realistically, Nelly, could the man you’re with resist reading Putain? She giggles. “I’m pretty sure he hasn’t. He doesn’t read any books, so why should he read mine?”

Tcharacters in À ciel ouvert and in Heather O’Neill’s Lullabies for Little Criminals inhabit more or less the same patch of Boulevard Saint-Laurent and its cross streets as Arcan takes up, though the time frame of O’Neill’s first novel is twenty years earlier, before gentrification hit, before you could get a Botox treatment, Portuguese grilled chicken, a $15,000 sofa, and a hit of ecstasy within a hop and a skip. The world of twelve-year-old Baby and her too-young father, Jules, an addict she both loves and laments, is a white-hot, dangerous place for one so innocent and alone.

During a crazy, transformative eighteen months, the motherless waif turns thirteen and discovers her body, along with the money and dubious sense of validation it can pull in. Like Arcan’s debut, this novel announced an unmistakably original voice. With a narrative pitch as seductive as the well-paced story it tells, Lullabies for Little Criminals is funny and clever, full of marvellous observations from a child savant who wanders into the shadows, arousing the reader’s fear and dread at every turn.

Heather O’Neill was born in Montreal. When her parents’ marriage broke up, she lived a peripatetic few years with her mother in the US before returning to Montreal as a teenager with her father and two sisters. In the flurry of media surrounding her literary debut, O’Neill suggested certain personal experiences had inspired the novel, but regrets it now, specifying that “the novel exists in the childish realm of make-believe.”

Slim and tall, with strong, sensuous features, she favours the casual Bohemian style of Plateau Anglos and plays with her tresses of loose, dark hair as she speaks. There are flashes of Baby’s guileless savvy in her mannerisms, as though some corner of her psyche is still a little girl. She was twenty when she graduated from McGill, and a few months later gave birth to a daughter, launching a difficult stretch as a single mother.

“I worked my guts out in clubs at night and tried to write during the day. It was killing me, burying me alive. My dad lived nearby and would babysit if she was sleeping. It’s odd when you have a kid that young; all your friends are living such a different life. I was still getting a thrill out of buying a pair of foxy boots, and yet I had all that responsibility.” At thirty-four, O’Neill has settled into a serious relationship with fellow writer Jonathan Goldstein, and is weighing the option of maternity once again. In contrast to Baby in Lullabies, the central character of her novel-in-progress is “someone who really likes sex, and that’s kind of fun.” She agrees with Arcan that sex is bound to be central to fiction reflecting the lives of women her age.

“If you’re young and attractive, it’s like having a walletful of money. It gets you things. Some people don’t want to admit it, but youthful beauty is powerful. No one is immune.” Reliable birth control and advances in the science of fertility mean women can play the field for thirty years and then become mothers. “The trajectory of a woman’s sex life is completely different now from that of previous generations. You have a long time to exploit your beauty.”

Lori Saint-Martin, a literature professor at uqam, has published widely on contemporary Québécois fiction by women. She points to Alina Reyes’s erotic novel Le boucher, published in France twenty years ago, as a breakthrough. “Reyes and others who followed made women the focus, not the object of desire, proving that transgression and taboo weren’t essential to the genre. This writing was mainly about having and giving pleasure.” With La vie sexuelle de Catherine M. (2001), by Catherine Millet, the well-known editor of a prestigious Paris art journal, the boundary between pornography and literature faded. Saint-Martin believes Millet’s novel, detailing the sexual exploits of a woman in her fifties, and L’inceste (1999), by Christine Angot, represented forays into a new feminine (though not feminist) discourse on sex, one in which the line between fiction and real life is blurred.

Marie-Sissi Labrèche, also of Montreal, embraces a loose, colloquial language, veering toward effervescence, which may explain why her breathless account of growing up wild has generated considerably more warmth among critics and readers than have the novels of Arcan. Borderline, published by Boréal in 2000, recounts the troubled childhood of a character named Sissi, brought up by a manic-depressive, schizophrenic mother and an abusive grandmother. Her second, La brèche (a pun on the author’s surname, which means “the breach” ) deals with a young literature student’s tortured affair with her married professor, a power struggle in which abuse seems to works both ways: the lover is described as “a man cornered by a small blonde bombshell.”

Sex is alternately the narrator’s weapon, her obsession, and an escape from the anxiety of a troubled identity. In Sissi’s words: “I’m borderline. I have a problem with limits. I make no distinction between exterior and interior. It’s because my skin is inside out. It’s because my nerves are on edge. I feel like everyone can see inside me. I’m transparent.” At twenty-three, she is desperate for love. The moment a man flashes interest, she opens her legs.

Literature exploiting lived experience is a genre Labrèche and a number of other young writers take seriously. A graduate of the uqam literature program, she wrote her thesis on auto-fiction; her first novel began as a course assignment. Her recently published third novel, La lune dans un hlm, is more conventional in structure. Personal details recur — mentally ill mother, difficult grandmother — but the main character (now called Léa) has gained distance on the past. And Labrèche, now happily married, says, “I’ve made up with all my demons.” A film drawing on her two first novels, which she co-wrote with director Lynne Charlebois, opened in February to great reviews and brisk box office. She has put prose aside for the time being to develop a TV series.

yvon Rivard is a respected novelist and literary critic. This year, he wraps up a distinguished career as professor of literature and creative writing in the French department of McGill University, during which he shepherded over a hundred theses (written in French) through the academic mill, half of them works of fiction. He counts dozens of published writers among his former students, notably Shanghai-educated Ying Chen, who began writing fiction in Rivard’s course and has gone on to publish six internationally acclaimed novels. Rivard has made it his mission to instill the virtues of storytelling and “finding the bones” of narrative structure. With a syllabus some might consider old fashioned — Raymond Carver, Mavis Gallant, Alice Munro, Katherine Mansfield — he disdains the poetic novel. Good fiction, Rivard maintains, is “planted in something real.”

“I don’t want to get killed by my male friends,” he says with a grin, “but women are writing the best books. Feminine writing is where one finds originality these days. If I can be permitted to generalize further, I’d say women have a more complex and subtle notion of time; males tend to be abstract. When I look over my classes, I’d say that the hybrids, the fusion of immigrant and old stock, and, yes, the women — they are the future of literature in Quebec.”

His latest discovery is Romanian-born Irina Egli, whose first novel was published by Boréal in 2006. Set in the port city of Constanta, Romania, on the Black Sea, Terre salée is an atmospheric love story charting the destruction of a middle-aged physician who falls into an obsessive love affair with his eighteen-year-old daughter. With a cast of high-strung characters and lush, confident prose reminiscent of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet, the novel revisits the Oedipal myth: a clear-eyed young beauty defeats her mother and her father’s mistress in a battle for his love.

Egli lives alone in an artfully decorated loft overlooking Montreal’s business core. She was born in Bucharest and published short stories and poetry before immigrating to Quebec in her mid-twenties, a decade ago. She speaks English fluently but chose to write fiction in French, a language she deems more literary and closer to her native Romanian.

An only child whose parents divorced when she was four, she rarely saw her father after he started a second family. “In most of my personal relations, I look for my father.” Terre salée tackles the missing person head on. The psyche of the lover, Alexandru, merits the most attention; Anda is presented as a poisonous siren who exploits the power of her beauty, but if the poet Ahoe’s sentiments are to be believed, not without purpose: “Men are small. Very small. Only unhappiness can turn them into giants. In their own eyes. Uniquely. Remember that!”

The second volume of her proposed trilogy, tentatively called Ange de passe, to be published by Boréal this fall, follows Anda to Montreal, where she undergoes a self-destructive purge of her demons by way of sexual experience.

“For a curious person, sex is a door,” says Egli. “You go through it — why not? Seduction is always about power, but finally the experience has to lead somewhere else. But where? We’re lost in the modern world, too pragmatic, material. Can we still believe in gods today? The Greeks knew a lot about the subject, the rituals and transcendent meaning of the flesh.” The trilogy, she says, is meant to be an exploration of how the pre-Christian themes of Greek mythology play out in modern characters and situations.

Sex as rebellion, revenge, adventure, boost to self-esteem, cry of desperation, bargaining chip in the quest for love, source of income — the current crop of new novels by young Quebec women investigates an enormous range of motivation. Yet there is precious little interest in pleasure.”

A generation has come along writing novels about sex that aren’t meant to be erotic,” says Lori Saint-Martin. “Quite the opposite, they’re often very sad, existential, inspired not by any sense of the erotic, but by the genre — auto-fiction, writing about yourself. One thing a young woman has to write about is her sex life. It’s a source of identity, a mystery, and of course power. There’s a huge narcissism involved, often self-hatred, and very little interest in exploring eroticism.” And yet, as Saint-Martin points out, publishers are quick to trade on their authors’ youth and sexual appeal, plastering book covers with steamy promises and photos of the writers wearing vixen smiles and provocative outfits. “The whole thing is quite ambiguous.”

In L’homme ligoté, Anne-Rose Gorroz tackles a sado-masochistic relationship. Each time the narrator and her lover meet, he presents her with another version of his desire, a kinky game that horrifies and fascinates her.

The dark side of eros propels Marie Hélène Poitras’s Soudain le Minotaure, published in Patricia Claxton’s translation as Suddenly the Minotaur by DC Books. A spare novella, it probes both the sexual fantasies of a serial rapist and his victims’ quest for healing. But by and large in the works considered here, missing along with pleasure is any hint of the redemptive potential of the sexual act.

The overarching presence of sex as power play may be a natural consequence of youth embracing a decayed taboo with audacity, the palace of wisdom being still a ways down the road of excess. Yet an aura of solipsism, even self-absorption, lingers. Arcan’s latest novel goes furthest in attempting to grapple with the wider social implications of complete sexual licence. In À ciel ouvert, one of the two main characters, Rose, muses on the cruelly competitive world in which women are driven to despise each other and mutilate their bodies in order to land a man. Her diagnosis is essentially material: there are far more beautiful young women on the Plateau Mont-Royal than there are fuckable men—hence the brutality of the game.

This application of marketplace values to the realm of human activity makes for a troubling bit of analysis that even the Marquis de Sade and his legions of acolytes have argued is philosophically, sometimes politically significant. But he was old when he wrote his major works. Chances are we haven’t heard the last of youth and beauty.