Last Easter Sunday, not far from Maiwand, Afghanistan, as the Royal Canadian Regiment battle group was on security detail, travelling in armoured vehicles along Highway 1, a blast went off. It left one vehicle a smoking ruin and six soldiers dead, Canada’s biggest single-day loss in Afghanistan up to that point.

Hemmed in by mountains to the north and desert to the south, in a region infested with Taliban fighters, Highway 1 has once again become a scar on the face of Afghanistan. It is the main route east and west through this region — as it has been for a thousand years — and according to Lt.-Gen. Andrew Leslie, chief of the land staff for the Canadian Forces, more than half of Canada’s seventy-odd combat deaths have occurred within twenty kilometres of this stretch of road near Maiwand, west of Kandahar. The throughway was a channel of death for the ancient Greeks and Persians, for the British and Soviets, and now for the Canadians. Along with the route from Baghdad to its airport, Highway 1 is one of the most murderous stretches of road in the world.

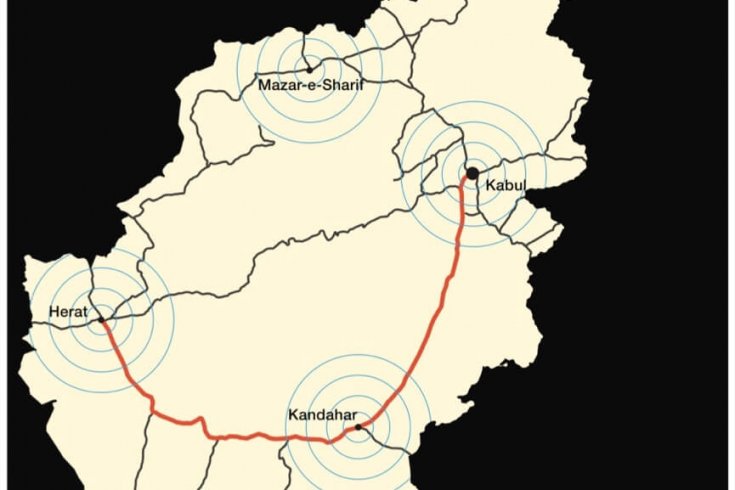

Forming the southern half of the ring road that circles the impenetrable central mountains of Hazarajat, Highway 1 traces an arc from Kabul in the east down to Kandahar in the south and up to Herat in the west. Sixty-six percent of all Afghans live within fifty kilometres of the ring road, 63 percent of the country’s cultivated land lies within the same area, and it’s along Highway 1 that the war in the south is largely being fought.

The Helmand River valley, whose poppy fields supply the Taliban, crosses the highway, and by 2006 the valley had become the rear supply base for the Taliban’s primary objective: seizing Kandahar. The Pashtun tribal belt (with which the Taliban identifies itself ) follows the southern arc of Highway 1. Janice Stein, director of the Munk Centre for International Studies in Toronto, says that for the Taliban, control of Kandahar would mean control of the south. Kandahar is the traditional capital of the Pashtun region — and the historical rival to Kabul — and gaining control of it might well be a prelude to reconquering the country. Lt.-Gen. Leslie argues that the Taliban will not take the route from Kandahar to Kabul using only guerilla tactics. However, were they to win the south, in the more conventional war that would likely follow it would be far easier for them to seize Highway 1 to Kabul.

A good measurement for the success of the nato-led International Security Assistance Force (isaf) in Afghanistan is the degree to which it is able to secure the entire ring road. But, says Steve Appleton, the former program manager of road construction for the United Nations Office for Project Services, progress has been slow, and the results are unsettling. Perhaps this is why the ring road is rarely discussed during Canada’s rather abstract national debate on our involvement in Afghanistan. Stein suggests that public and political discourse focuses on matters such as destroying poppy fields and building the Kajaki hydroelectric dam because these objectives are more circumscribed and more easily defined. Nonetheless, Highway 1 remains the artery by which these and other missions must be supplied, and there are simply not enough troops to secure it for any significant period of time.

From war, neglect, and sabotage, much of the ring road is in ruins. As the Western allies try to rebuild it, the Taliban consistently try to stop them. They have murdered Turkish road engineers and contractors, and killed, kidnapped, and decapitated Indian engineers working on the Herat stretch and the new Delaram tributary road in the west. Appleton (now retired) says that not even Highway 1 is complete — as some in nato’s isaf would have us believe — to say nothing of the entire ring road. This spring, insurgents blew out the road east of Kandahar, and fear of attacks brought construction to a halt around Lashkar Gah. Iran, which was to complete the ring road stretch north of Herat through Badghis province, seems to have reneged. Alarmingly, says Appleton, there are rumours that some Afghan construction companies are now Taliban controlled. The ring road is a lifeline, and to the Taliban destroying it is almost as good as seizing control of it.

On maps of ancient trade routes, one finds the intersecting paths of today’s ring road around the central mountains. Alexander the Great took the region by following part of the route from Herat to Kandahar and almost the exact course that Highway 1 now takes to Kabul. In the eighteenth century, Pashtun conquerors, the founders of modern Afghanistan, marched the old India-Persia trade route from Kandahar to take Herat from the Persians. In July 1880, a British force moving along the route near Maiwand met with disaster at the hands of Afghan rebels, right near where the Canadians died this past Easter.

Years before Moscow invaded in 1979, the Russians made the ring of dirt roads into a crude cement highway. Anton Minkov, from the Centre for Operational Research and Analysis at Canada’s National Defence headquarters, says that during the 1950s and ’60s, as the Soviet Union and the United States were vying for control over Afghanistan, each built sections of

Highway 1: the Soviets doing the Herat-Kandahar stretch, the Americans Kandahar to Kabul. In the north, the Soviets paved connections across their own border to tie Afghanistan to the ussr and for invasion purposes; from the first, the road was designed for heavy military transport.

The Soviet strategy was to take the main cities and secure the ring road that bound them. But their army ran into the same problems the isaf is facing today. According to Minkov, every single Soviet convoy that ran along Highway 1 was attacked, and 25 percent of the Soviet troops in Afghanistan were tied up in the ring road’s defence. In the end, 11,000 military trucks were destroyed, and the Soviets never realized their goal of taking Panjwaii, the western gateway to Kandahar.

The area around Panjwaii is the ancestral home of the Taliban, and the village of Sangsar, a short distance to the north in Uruzgan, is said to be the birthplace of the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Omar. Omar founded the Taliban partly to eliminate extortionate toll stations set up by local warlords along Highway 1 after the Soviet withdrawal. In the civil war that followed, the Taliban took Kandahar and made it their capital. During the fighting, the entire ring road was destroyed. After the Taliban took power, they left it in ruins because, they reasoned, restoring it would open the door to cosmopolitan influences.

Following the US-led defeat of the Taliban in 2001–2002, aborted highway construction projects of a half-century ago were resurrected. The rebuilding of Highway 1 began in 2002 with primary funding from the US Agency for International Development ($80 million) and Japan and Saudi Arabia ($50 million each). The total estimated cost was $250 million, and there was clear determination to complete the job, because without this road there would be no Afghanistan.

Landlocked Afghanistan has no coast or defining waterway. It has always been a transit route for surrounding powers — and often a power vacuum at the centre of them — and the country’s tendency is centrifugal, with ethnic, linguistic, racial, and tribal loyalties often splintering. This, combined with its famously difficult terrain and remote settlements, has made centralized control and planning all but impossible. Still, it is a place badly in need of common bonds, and the ring road could bring myriad agricultural enclaves into a national economy by transporting produce to markets (the Kandahar-Kabul stretch is the most crop-intensive area in the country),and providing mobility for workers, which would drive up employment. Before the war with the Soviet Union, when the road was unbroken, Afghanistan’s major export of dried fruit was five times what it is now. Above all, the ring road is needed to extend Kabul’s rule over the country, uniting the alienated, disenfranchised Pashtuns in the south (where the Taliban finds its recruits) with the more peaceful north. It could bring back the people of remote regions who trade independently with Iran and Pakistan, and tie Afghanistan to the economies of India, Pakistan, Iran, and Central Asia. (At the end of the nineteenth century, this is what Afghanistan’s Amir ‘Abdor Rahman Khan attempted by turning the trade routes into a circular thoroughfare. Paradoxically, for the same reason the Taliban refused to restore the ring road, ‘Abdor Rahman refused to build a single railroad: it would provide a means for outside powers to secure interests inside Afghanistan.)

In the north, the ring road remains broken and is actually nonexistent in some areas; in the south, the Taliban attack Highway 1 relentlessly. While nominally controlled by the isaf, the north-south river valleys that cross Highway 1 are in the vise grip of the Taliban, and the war against the insurgents will not be won unless the area’s supply depots are eradicated. The line with which the Taliban supplies the Panjwaii area begins in Nushki, Pakistan, far to the south. It runs across the border, northwest along truck tracks across the Rigestan Desert to the lower Helmand River, then by river to their supply base at Garmsir, and up the Arghandab tributary to Highway 1 and Panjwaii, just west of Kandahar. Cutting that supply line would help secure the highway and protect Kandahar, but to date no such effort has succeeded.

Canadian Lt.-Col. Omer Lavoie, who commanded operations in Kandahar in 2006, says that any invader who has wanted to take the city (from Alexander the Great on) had to take Panjwaii first. This the Taliban did. But as the district has some of the most recalcitrant and xenophobic tribes in Afghanistan, no outsider has ever conquered it. In the spring of 2006, after the Taliban dug in at the tightly packed villages and vineyards in Zhari district (above Panjwaii and on Highway 1), the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry repeatedly endured casualties on the five-kilometre stretch known as Ambush Alley. In September, Lavoie was given the job of clearing out the Taliban from Panjwaii and Zahri.

The insurgency’s plan, meanwhile, was to cut the highway at Panjwaii-Zhari and launch assaults to take Kandahar. Commanding the isaf’s Canadian-led Operation Medusa, Lavoie achieved early success, killing hundreds of Taliban fighters in ferocious engagements, and rooting them out of Panjwaii and Zhari. To help secure the district once and for all, Lavoie built a wide road into the heart of Panjwaii. The “Route Summit” connected Highway 1 to the Arghandab River, and significantly cut the response time for military operations while linking Panjwaii’s farm economy to Kandahar.

In general, the isaf uses an “ink spot” strategy to gain control of Highway 1. Scattered urban centres, or Afghan Development Zones (adz), are taken in combat and provided with security and development assistance that, in theory, will spread outward until the adzs link up, protecting Highway 1. Lavoie says securing the highway first could be successful, but he points out that the Soviets’ mistake was to restrict their operations to the highway at the expense of surrounding districts.

The operations led by Lavoie and his successor made the Qalat-Kandahar-Panjwaii stretch of highway safer, but the Panjwaii area itself has started to regain its reputation for viciousness. Before fleeing last fall, many of the Taliban buried their weapons and returned as farmers to booby-trap the highway and carry out ambushes and suicide bombings. Thus, last December’s Baaz Tsuka (a.k.a. Operation Falcon’s Summit), in which the Canadians pushed the Taliban out for a second time, became necessary.

Though Canada had the firepower to defeat the Taliban, it didn’t have the troop numbers to hem them in and prevent them from escaping. Over desert and mountain routes — and with astonishing speed — many moved far to the west to support a mushrooming insurgency in Farah province. Lavoie admits that Taliban fighters probably stow their weapons and resume their normal identities as farmers who fill the backs of pickup trucks on Highway 1, and Leslie says the Taliban most likely use the road to traffic opium, using the false bottoms of their trucks.

Early in the new year, Highway 1 was under renewed Taliban attacks in the west, all the way up to Herat. The stretches near Herat and Kabul (outside the Canadian and British zones) remain the most dangerous: in July, it was on the route through Ghazi, south of Kabul, that the Taliban kidnapped a busload of Korean missionaries. In these areas, crime and corruption are rampant, and Afghan auxiliary police are known to use checkpoints to extort money and/or goods.

By late summer, gains made in Panjwaii had been all but lost. The Canadians had moved west and south, only to see the Afghan police outposts they had left behind overrun by Taliban fighters. This September, Canada launched operations Strong Lion and Keeping Goodwill in a bid to get Panjwaii back.

Steve Appleton, however, provides a sombre assessment, arguing that security is declining everywhere in the country and that large highway construction projects are basically over. Persistent attacks have stopped work in some places, while in others foreign and Afghan contractors have cancelled projects or pulled out altogether. Where work persists, the provision of security for Afghan road crews and paying locals for “compliance behaviour” (essentially protection money) is driving up costs.

The insurgency, held down by the Canadians in Kandahar and pinned by the British in Helmand, has spread west into Farah and north into Herat and Badghis. It is following Highway 1 and the ring road around the central mountains and into the north. It could be just a matter of time before extremist and determined Taliban warriors get to Kabul.

While peace talks with moderate Taliban, regulating the production and marketing of opium, and providing development assistance are all important initiatives, Afghanistan’s lifeline is the ring road, particularly Highway 1. If Canadians want clarity about our mission in Afghanistan, the ring road should be put at the centre of debate. As Lavoie put it after inquiring of the locals in Panjwaii what they wanted, “The first thing they asked for was a road.”