I am in the philosophy section of the University of Toronto bookstore, looking for something by Hannah Arendt, whom I studied under in the 1960s. “Thanks for that column today,” says a man beside me. “You might like this book by Agamben, on states of exception.” The newspaper column he’s referring to was on torture and “the new normal” since 9/11. He hands me the volume and leaves. It’s slim and costs $13.85. I replace it and go, but as I cross College Street I realize it’s about something that has been preoccupying me, so I return.

That night, I wake at three and read it. Giorgio Agamben, an Italian prof, writes that the “state of exception,” also called state of siege, martial law, or state of emergency, has been common since World War I. In Canada, it was called the War Measures Act (now the Emergencies Act), and it was last invoked in 1970, on the day I returned from a student decade in the US. Agamben traces it back through history, including Germany’s Weimar Republic, pre-Hitler. He quotes Walter Benjamin on exception as the new normal. He even mentions Taubes. That would be Jacob Taubes, with whom I did my MA in religion before moving on to philosophy. Nobody quotes Taubes. The night of the blackout in 1965, I found him humming nigunim in the dark in his office — he came from a line of rabbis. We wandered Broadway, stepping into candlelit bars. But I digress. I was talking about the idea of uniqueness, or exception, associated for me with the Holocaust.

Among Toronto Jews in the 1950s, the Holocaust was inescapable. At Holy Blossom Temple, the grade threes did a unit on it. They composed a letter from someone their age in Nazi Germany. “Hello cousin Jake,” wrote one eight-year-old. “Here in Germany things are bad. There is an awful man named Hitler. He should be called Shitler.” They gathered on a sunny Sunday morning to hear a shaliach, an emissary from Israel, say, “The world is finally learning, through Israel, that Jewish blood costs as much as anyone’s.” Outside stood the stolid homes of Forest Hill. We were comfortable scions of a people for whom, as Shylock said, “sufferance is the badge.” It was hard to reconcile.

Gradually, the Holocaust acquired that centrality for more and more people. Every crisis evoked it. One had to learn from Munich to prevent another Auschwitz, and so on. It was used to justify interventions in Kosovo and Iraq. Saddam Hussein was worse than Hitler. Osama bin Laden was like Hitler and Stalin — it was as if one could not act until the action had been linked with Holocaust terminology.

But I don’t mean to cover the vast cultural space occupied by the Holocaust — its history as an idea. I want to focus on something smaller: its more compact autobiography in individual cases, in order to explore how the private itineraries of ideas can illuminate them. If that seems obvious — hey, who I am affects what I think — I don’t mean it as modestly as it sounds. Ideas have been treated deferentially in the Western tradition, from Plato, for whom they actually existed in another realm, to our age of experts, with authority in their “fields”: politics, sports, terrorism. There has also been a backlash, in extreme versions of postmodernism, as if ideas have no integrity apart from personal agendas. I want to examine this, not in theory, but through a particular example — the Holocaust — in my experience.

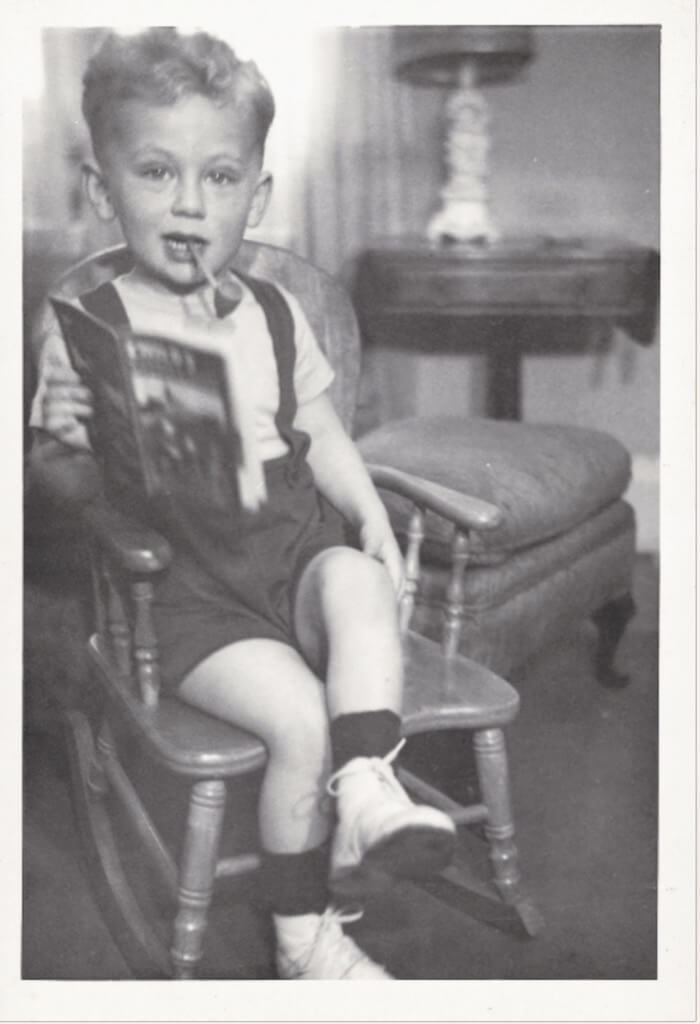

I became a teenage religious existentialist under the influence of philosopher and rabbi Emil Fackenheim. I met him at Holy Blossom, where he taught Jewish thought. I hung around there during adolescence as some kids hung around the mall, because I was trying to avoid home and my difficult dad. (So I now think. Who really knows?) We were a precocious lot, and Heinz Warschauer, the education director, thought challenging us might keep us involved “post-confirmation.” It did. We were enthralled by Emil’s accent, gentle manner, impish look, cigars, and redoubtable mind. We had Emil contests to see who could mimic him. We’d phone each other and pretend to be Emil. But his ideas dazzled me most. He believed in God, no apologies, yet was clearly brilliant. He even allowed for divine revelation and immortality. I’d thought those were reserved for the aged and the credulous. It even had scandal value: insisting on spiritual meaning in our crass, acquisitive community. I went for it.

I’d ride my bike to his duplex. I never said I was coming. I used to show up on people’s doorsteps, in search, I think, of parent proxies. You don’t call ahead for an appointment with your dad. Emil always invited me up. We’d sit in his study and talk about his latest book: philosophy of religion from Kant to Kierkegaard. I grasped little, but his attention and respect were precious.

He was ordained in Nazi Germany but escaped to the UK. When war broke out, he was interned as an enemy alien and sent to Canada with other German nationals, including Nazis. They were all held in camps. On his release, he rabbied for a while but got a Ph.D. in philosophy and began an academic career. In the camp, he met Heinz, who gloomily presided over the Holy B. school and convinced Emil to write a textbook on Jewish theology. It explored arguments for God’s existence and Jewish survival, among other things. Emil belonged to a mid-century surge of religious existentialism that challenged such smug modern verities as progress and rationality in the wake of the war and the Holocaust. It took categories like sin and God seriously. He wrote in magazines like Commentary. To me, it meant you could be brilliant, outrageous, and famous.

In class, the Holocaust might arise while discussing, say, morality. Then Emil would tell us it had been a unique historical event. “Because it was evil for evil’s sake,” he’d almost whisper, more hypnotically than ever. As evidence, he argued that the resources needed for mass murder undermined the German war effort and diverted scarce materials from military use. The Nazis knew it but persisted. It was unreasonable, he said, and self-destructive. It proved the Holocaust was evil. It served no other end.

This argument fascinated me. It stayed with me long after we lost touch — as if it held a meaning I’d finally discern if I turned it over and over, as the Talmud says one should do with the Torah. Perhaps we all have intellectual touchstones — arguments, images, phrases — that seize us and that we in turn seize.

I wondered, even then, if the Nazis really were irrational. Perhaps they employed a bizarre logic. If Jews were the ultimate cancer, a germ infecting the species, then destroying them might trump such short-term goals as military victory. If it looked likely that they’d lose the war, as it did once the US entered, there might even be a ghastly selflessness in trying to destroy the viral race — even as one perished. It all followed only, of course, if you granted the inane premises: that race exists in a meaningful way; that it is the chief determiner of global history; that there is such a thing as global history; that individual lives matter little compared with grand patterns; and that Jews are a vile race. None of this shook my sense of the Holocaust as a unique horror. But it made me think; it set me up to ask other questions in coming years. The trick, I now feel, lies in figuring out the questions that were on your mind, which led you to accept or reject certain answers or attitudes. What is bugging you. What was bugging me?

During the 1960s, Emil attended yearly gatherings in the Laurentians of like-minded Jewish thinkers. There, he said, he met the high priest of Auschwitz. It was Elie Wiesel. Wiesel’s readiness to confront the Holocaust stunned Emil. I went one year, as part of a small “youth” contingent. On a long walk, Emil told me he realized that for twenty years he had been trying to clear a place for faith after Auschwitz, yet all along he’d failed to tackle faith’s main stumbling block: the Holocaust.

It was a turning point. He finished a book on Hegel and began writing about faith — not so much after Auschwitz as in its harsh shadow. He also declared that there was now a 614th commandment (the traditional number of laws in the Torah is 613) — Emil later sometimes called it the eleventh commandment — for Jews after Auschwitz: thou shalt not allow Hitler posthumous victories. Emil said that had been his purpose in all he had written on faith: denying Hitler another triumph. His life and thought were permanently recast. I suppose that happens in life. But for most intellectuals, the existential fulcrum tends to become obscured until only the abstract conclusions are visible. The biographical elements get hived off from the conceptual results. Emil took the opposite route. From then on, he wrote everything based on who he was and what he had lived through.

In June 1967, Emil despairingly watched the outburst of war between Israel and the Arab states. He feared Hitler was about to win another victory. Then Israel suddenly and totally triumphed. In our conversations at the time, it seemed clear to me that Emil felt that was in some sophisticated sense a miracle, that God had intervened. The presence of God in history was part of his theology. He did not affirm literal revelation of scripture, but he believed in an existential encounter between the “Eternal Thou” and the Jewish people. It was a bold way to introduce a transcendent quality into worldly reality. Applied to the Middle East in 1967, though, it was risky. For to claim that Israel owed victory to divine intervention, one had to accept the version of events provided by Israeli officials and the Western media — and that was questionable. Perhaps Israel had not been so exposed. What if its resources were in fact superior, and its leaders knew that but for strategic reasons claimed the situation was dire? In that case, Emil’s anxiety and that of others, including me, was due to propaganda, and there was no need for intercession from above. He had begun moving down a dangerous path, placing his faith at the mercy of diplomatic and journalistic exercises.

We stayed close. When I left to study in the US and Israel, he handed me on to others, who handed me on to others. In 1964, he officiated at my wedding. He gave an exquisite Midrash, a rabbinic sermon, on marriage. It was one reason I stayed in an ill-starred marriage as long as I did — the sad thought of him preaching in vain.

In 1965, while I was at both a rabbinical seminary and grad school at Columbia, I sat in a coffee shop on a grey, rainy afternoon. I was in a gloomy state over my marriage, my unease at seminary, and, maybe, the state of the world. The Vietnam War was poisoning discourse in the US. I was no leftist; I still saw the world in religious terms. To me, politics seemed superficial. If anything, I leaned to the right. I finished a grey cup of coffee and watched a column of police officers march briskly onto the campus. I paid and followed. By the time I got there, a melee was in full flow. Bodies were being flung down the wide steps of Low Library — not a real library but the main admin building. I headed up to see what was going on.

At the top of the steps before the domed building, police had disrupted a protest against campus military recruitment. What I saw was not just protesters being hauled from a line. It was excitement in the faces of the officers and animation in their bodies. Many protesters were long-haired women with something provocative in their dress and hair, and the police violence felt like a response. That’s what hit me: the engagement of the armed agents of the state. They were not just doing a job or maintaining order. They were into it, as one said. And I thought, this is how it was in Nazi Germany. The entire conceptual structure I’d imbibed, including the uniqueness of the Holocaust, crumpled. People are capable of this, I thought. They just are.

Put these cops in Nazi Germany, and some would do what the SS or camp guards did. The uniqueness of the Holocaust and any ideas built on it melted away. So this is what the force of the state is about, I thought — and human nature, too. That experience led me to leftist politics. When someone had to risk his academic career by speaking out, I would volunteer cheerily, as if I’d already written off the future of my past. I wrote my comps but didn’t advance to a thesis. I spent a summer on an island in Temagami reading through a small mountain of Marxist economics. My relationship with Emil did not weather these changes well.

When I returned to Toronto in 1970, I went to see him. He said, “I don’t like what I’ve heard about you and Israel.” I found it abrupt, but it was true, I had changed. I’d been in Quebec City, where I’d gone to rent a garret and become a writer. It’s odd that we never discussed my fall from faith; it didn’t seem to interest him, nor me either. We had both been absorbed in some way by politics.

After that, our contact waned. In 1982, when Israel invaded Lebanon, I wrote a piece for Maclean’s called “Hitler’s Haunting Last Laugh,” in which I mentioned Emil’s new commandment. I wrote that supporting the invasion amounted to ceding Hitler a belated victory. Emil wrote in, angrily dissociating himself from my use of his words. We had sporadic, indirect, always bitter contact. He retired and moved to Jerusalem. Years passed before we met again.

In the late 1980s, Dow Marmur, rabbi at Holy Blossom, told me Emil would be in Toronto again. Dow asked me to come. When I winced, he said, “I’ll stand between you.” After speaking, Emil signed books. I got in line. He looked up, and I said, “It’s Rick.” He pushed his glasses onto his brow (another lovable trait) and rose, then we embraced. We met the next day, and I brought up our disputes. He said, “We can talk about that. Or we can say, It’s in the past.” I suggested we talk a little. We got nowhere, but it didn’t matter. We were back in touch. On his eightieth birthday, Holy Blossom held a dinner, to which I went.

It all came apart again after September 11, 2001. Someone told me, “Emil Fackenheim mourns for you.” I got a tart email from Jerusalem. Emil said he had followed my recent writing, and “of course” I was wrong. Then he veered off. He said when I was sixteen, he had judged a sermonette contest I had won, but that I had quoted a verse from Exodus without mentioning the next, which contradicted my point — as though he would revoke the prize now if he could. I pondered for months how to reply.

A copy of his email was still sitting on my desk when I heard he’d died. Then I realized I could have said something about his famous phrase, my use of which incensed him. It was open ended, that eleventh commandment; it said how to approach your obligations as a Jew but not what to actually do. It left that to each of us in our situations, much as the categorical imperative of Kant (whom Emil revered) said only in the broadest terms what to do. Kant and Emil both left the living of life to free choice. He had respectfully cleared that space, in spite of how vehemently he might have disagreed with the decision in my case.

After 9/11, evil was in the air again, as though it were the true source of the attacks. There was also a sense that 9/11 was, like the Holocaust, unique. It changed the world forever, people said; nothing would be the same. They sometimes mentioned, for contrast, Hannah Arendt’s phrase, the banality of evil, deployed to describe the Eichmann trial forty years before. But 9/11 didn’t seem banal. It was spectacular: huge towers collapsing as if swallowed by the earth. I found the question confusing. The drama and symbolism of 9/11 were surely unique, but they were hard to square with the grimly ordinary result: some 3,000 innocent lives extinguished in the name of cause and grievance, hardly a rarity in our time. It didn’t change everything, except for those to whom it felt that way. But that is true of all catastrophe: a single death in traffic changes everything for those involved.

I studied with Arendt at the New School after drifting out of the seminary/religion stream. At first, I didn’t know she was Jewish, or that she spent almost a decade after she fled Nazi Germany working for Youth Aliyah in Paris, helping Jewish kids reach Palestine (as Israel then was). She was a great teacher. She had a direct quality. “Look,” she said when some of us informed her during a class on violence that capitalism is inherently violent, “violence is when he hits you.” I became not a disciple, exactly, but I still take a regular dose of her writing and always come away improved. Post-9/11, a book of her essays jumped off the shelf into my hand one day. Then a few pages from a 1950 piece called “Social Science Techniques and the Study of Concentration Camps” leapt out. Near the end of World War II, she wrote, the gas chambers were counterproductive. Himmler knew it. Yet he ordered that “no economic or military considerations were to interfere with the extermination program.” This “for all immediate practical purposes [was] self-defeating.” It was the same argument I had learned from Emil.

I don’t find this kind of thing repetitive. I find it to be an opportunity to grow and learn. We revisit scenes of significance because we have not yet solved the conundrums of our lives. I returned to Toronto, I now think, not just because I ran out of money and terminally alienated my department with my fevered leftism. I came back because I wanted to deal with dilemmas I hadn’t solved when I left (and which were why I left). You can’t choose what perplexes you, but you can sometimes decide to confront or evade it. Long after I first heard Emil’s argument, Arendt’s essay gave me a chance to fixate on it again.

“Normal men do not know that everything is possible,” she wrote, quoting a Buchenwald survivor. But it seemed to me that many “normal” people know everything is possible. They may shake their heads but are not surprised. Arendt feared her colleagues would be stymied by Nazi conduct, since they would not comprehend how “objective necessities . . . adjustment to which seems a mere question of elementary sanity, could be neglected.” She meant such necessities as using trains to get troops to the front. But I don’t find that hard to grasp, and I don’t think I’m abnormal. People routinely fail to do what seems practical, because what matters in their eyes often has little to do with rationally calculated benefits. Irrationality — in the sense of impractical, short-term, or counterproductive — is chokingly common.

During the 1837 rebellion in Upper Canada, the beaten rebels retreated to Navy Island, near US territory below Niagara Falls, and exchanged cannon shots with imperial troops on the Canadian side. According to one of the accounts I read, a Loyalist volunteer named Miller — an “old Navy man” — had his leg ripped off by a cannonball. “After the mangled member was cut off, he desired to see it, gave three cheers for the Queen” — i.e., Victoria, crowned in London that very year — “and in a few hours was dead.” He made sense of his life by giving it away gladly, even giddily, for the sake of a young queen who would never know his name.

I have been thinking about Miller for thirty years. If I can understand him, I thought, I’ll understand what there is to know about human behaviour.

So who are the “normal men” who do not know everything is possible? I ask since I find the varieties of common sense to be more diverse and mysterious than Arendt and Emil thought, and any calculations made by Miller and others (like my dad, who I’ll get to) are usually far from utilitarian. What seems to me abnormal would be a world in which people lived rational, utilitarian lives and act commonsensibly. That sounds more utopian than the lives we see in history or on our streets. But that may say as much about me and how I have come to view the world as Arendt’s views do about her. Hmmm. Why did she see things just that way?

Well, it sounds like the world view of the European bourgeoisie: self-serving and proudly practical. The putting and taking satirized by Dickens in Hard Times or scourged by Eliot in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” It was ridiculed — but only because it was a worthy target, embedded like the religion or ideology of its time. We forget the power of such a moment, because once past it exists in a diminished state. Mighty fortresses become windmills to be gently tilted at. Our own graven images will be diminished, too.

Arendt was a child of that bourgeoisie, born in its twilight, in 1906, to a non-religious German Jewish family. The rest of her life amounted to being torn from that setting, seeing it pulverized around her — the Nazis, the trenches, the Depression — yet she writes, I’d say, as if the demise of her childhood world was the end of a geological era and not just one limited episode.

Emil had a similar, though more religious, background. His father owned a department store in Halle, in what became East Germany. His family was rooted in German and Prussian culture. After the Cold War, he received compensation and died wealthy, friends say. He was born a decade after Arendt, but perhaps shared her sense of bourgeois culture as an ethical baseline for human nature.

I don’t mean that either held a bourgeois view of human nature, or even an explicit view of human nature. But their notions of “normal” human constraints may have to some extent — without being quite aware — harked back to that world view. Did they do so in revulsion at what happened around them? It sounds crudely Freudian.

Mind you, Freud was one of many who repudiated the bourgeois view of human nature. He did so long before the Holocaust then died on its eve, having chillingly anticipated it with notions like the Id, which undermined civilization’s efforts to be civilized. Back then, there was a cottage industry in rejecting the bourgeois ethos, like Antonin Artaud’s theatre of cruelty. Nazism itself banked on anti-bourgeois disgust. In fact, it is surprising that German Jews such as Emil and Arendt could say they were surprised by the descent into barbarity. Horrified and enraged but not startled. Unless it is one thing to anticipate theoretically a breakdown of civilization, but something else to see it embodied before your gaze while you pass through the fire yourself. That might send you scurrying to an earlier world view that once seemed banal. I can sort of hear Arendt say, “Look, Artaud was theatre. Freud was theory. But this happened. No one really expected it.”

Emil underwent Freudian analysis in Toronto but remained skeptical of broader applications. He’d say, in what he called his deadpan, “That’s like treating a sick horse with a pill through a blowpipe: everything depends on who blows first.” Still, he didn’t deny it — he just said something witty about it. As for Arendt, she rejected interpretations based on unconscious motives. She felt they deprived people of dignity. “Look,” I can hear her say again, “he says that’s his reason. If I don’t take him seriously, why should I take you, me, or anyone seriously?” She believed in will and choice and would not see them disparaged. Despite that, her writings include brilliant construals of the “real” meaning of events. As if she could not refrain from them. I don’t think that makes her inconsistent. There is a realm of will and choice, and an area of murk and uncertainty. They interplay like light and shadow.

As for me and my reactions — to Auschwitz, 9/11, the cops at Low Library, and other evil moments of my times? My version of common sense tends not to be perplexed by vile behaviour. I am surprised when people act well. I’m guessing it has to do with my dad.

He was prone to exploding, for no apparent reason. I used to think it was tension over his gambling debts or his fraught relations with his older brother, Al, who dominated their little business in the garment district on Spadina Avenue in Toronto. Or resentment of his own dad, who did nothing, he said, except neglect his family and run around with women. Perhaps he was just born mean and stayed that way.

At any rate, it was brutal. Screaming, abuse, derision. Mostly at my mum, for being stupid, incompetent, when he couldn’t find a tie or we were leaving on a trip. Though they had a stupendous sex life. Everyone noticed it (except me, but that’s another story, er, novel). She later told me he still came home for “lunch” when I was in high school. Until a year before his death at eighty-five, it continued at least three times a week. I asked if she ever had an orgasm, and she guffawed (not her usual mode). “Every time.”

My brother and I had no such compensations (her word for why she stayed). Dad would wake me in the middle of the night, bellowing that we’d be on the street tomorrow and it was my fault. When I had trouble with high school authorities, he said they were right. I said, but they’re wrong! “Even when they’re wrong,” he shouted, “they’re right!”

He bullied us because he could. When he was dying and still bullying my mother, who’d been ill for years, I said she’d go the day after him if he kept on. He said she had to die sometime. That’s when it struck me that he knew what he was doing, and that it was wrong. But he had learned that there would be no consequences.

It wasn’t Auschwitz, I know. Yet the possibilities of awesomely cruel behaviour were established in my mind then. When a kid sees his dad behave that way, he knows — or at least I think I did, like the Buchenwald survivor quoted by Arendt — that everything is possible. If my dad can let go like this with me, he can go to the end; nothing will surprise me. Like my sudden sight of the cops at Columbia. They weren’t the SS, but in other circumstances some would have been. The possibility of the Holocaust was contained in those dynamics in our apartment, whether it seems ludicrous to compare or not. My dad had good points — he wasn’t a Hollywood monster, but he had monster potential. I can’t ever be surprised when people behave wretchedly.

Of course, neither Emil nor Arendt were surprised at the brutality and barbarism of Nazism; they knew those were hardy perennials that weren’t blooming for the first time. But each insisted on the uniqueness of the Nazi case: Emil because it was self-destructive, and Arendt because of the cold intellectuality — that it was based, not on emotional satisfaction, but on logically carrying an ideology to the end. You can call these crucial differences amounting to something new in history, or you can say they’re mere variations. Nazi motives were articulated ideologically. But does that mean they got no traditional vicarious, sadistic release? I doubt it. There’s always something new and something ancient, a particular version of timeless impulses. Everything was always possible.

Now to backtrack (revisit, regress): why did just those pages by Arendt on the Holocaust leap out at me? And why now? Well, our milieu is dominated by the aftermath of 9/11 and its sense that everything has changed, that the world will never be the same. For me, those claims evoked earlier ones. (And not just me. The Holocaust was widely invoked post-9/11. Americans tended to identify with it, as if only the Holocaust was unique enough to compare. It also fit their sense of exceptionalism — both Jews and Americans as chosen — and US fundamentalism, with its messianic and catastrophic expectations, easily attached to 9/11 images.)

So something in the similar backgrounds or social conditioning of Emil and Arendt influenced their responses to the decisive event of their time. And something in mine — perhaps my dad’s screaming fits — shaped my response to their responses. Nothing surprising here. Then another event — 9/11 — evoked those earlier responses, and a new set of reactions.

This endless personal context of thought is what I want to insist on — even for the heaviest thoughts of the weightiest thinkers on the thorniest topics. Each idea arises in a context, a moment in the chain of associations and digressions that comprise a conscious life. You can strip it from its context and lend it a certain autonomy, disconnected from life, but that won’t change its provenance, which affects its content and authority. Most intellectual history takes account of the autobiographical setting of thought, but as lip service, the way biographies often deal with childhood: a quick chapter left behind, rarely treated as the decisive period in every life ever lived, its effects reverberating till the end. (Rosebud, Rosebud — always Rosebud.) We remain the kids we were, and our ideas stay rooted in our autobiographies, far more than is usually assumed. Those bios are not mere backdrop for the thoughts. The thoughts don’t exist apart from the lives in which they are embedded. They are warp and woof.

I hope it doesn’t seem tawdry to use the Holocaust and 9/11 to make this simple point. Perhaps I’ve leaned to overkill since the approach — replacing the majestic history of ideas with more modest autobiographies or diaries — runs against the Western intellectual tradition, where ideas have tended to have lives of their own, literally, like Plato’s forms, or embodied historically, à la Hegel. When I studied philosophy, a notion like free will seemed to migrate from thinker to thinker and era to era, like a worm wriggling across a Persian rug. When an idea inhabited actual thinkers, it did so like a parasite in a host, who is optional or interchangeable.

I don’t believe this diary approach diminishes the role of thought. But it emphasizes thinking itself more than its end products — ideas, knowledge, truth. Knowledge seems to captivate us, yet, as Arendt said, what we are good at is thinking rather than knowing. Our instruments for knowing — our minds — are only capable of partial approaches to truth, because we exist in particular contexts: our lives and times. Less partial, perspectival beings, like gods or angels, would do better. That doesn’t mean we’re hopelessly confined within our views. We can access the perspectives of others and by a collective, democratic process build toward a larger view. But there won’t ever be a grand synthesis, putting it all together, because, well, who would do that? No one can get outside their perspective. It’s only the process itself that can do the synthesizing.

You can call this relativism, but not in the sense that nothing is true or everything is equally true. It’s a relativism in which there is no complete truth, and humans, as “finite modes,” in Spinoza’s mind-bending coinage, catch only partial views of the whole. So, in the absence of a perspective taking in everything, we must constantly turn the kaleidoscope to get a better view while never seeing it all at any moment. We must count on one another to complement and supplement — there is no alternative. The point is not that the Holocaust was unique or that a new historical moment had arisen. Or that it was instead a variation on an old theme, as I’ve suggested. It could to some degree be any, none, or all. Since this provisionality is the way to truth for us, it seems to me useful to shed light on the origins of ideas, since their meaning will be illuminated and inflected by their provenance. It is an argument for the role of origins in ideas, not for the invalidation of ideas by virtue of their having origins.

Nor does it mean everyone is right for themselves, in a postmodernist way. You can be more or less right, or wrong, depending on how well you reason with the materials you and only you have at hand. There must be a broad playing field on which all thought takes place, or else we wouldn’t be able to communicate at all. But the “rules” involved hardly suffice to bring us to identical conclusions on most matters, given our particular starting points. In fact, uncovering the constraints that act on your thinking — what Harold Innis called your bias, whether it’s personal bias or the bias of the “civilization” in which your thought developed — is the best way to move past those limits to something broader and truer. It’s like realizing you’re in a forest or a cage. Then you can start mapping it and look toward what may lie beyond.

I don’t find this discouraging. I’d say it makes thought more interesting — an endless, evolving detection process. And it explains why philosophical activity (in a broad, non-specialist sense) never ends, yet seems to make no progress: because serious thought is always part of someone’s biography. There is no way to transfer others’ thoughts to you, since one size always fits one. Words and concepts are not the same from person to person or situation to situation. All conclusions must be reformulated, rethought, and brought home, as it were. Does this reduce serious thought to saying, I think, and attaching your own ideas? Yes, basically. This is what makes philosophy a universal human activity, not in the old sense (because everyone has access to it through their inherent rationality), but because we all must do it for ourselves.