“Niqab, hijab, burka — I don’t think they are religious requirements, they are cultural requirements.”

– Ghayasuddin Siddiqui of the Muslim Parliament of Great Britain, a leading advocacy group, quoted in the Globe and Mail, October 23, 2006

An Anglican school in England suspends a twenty-four-year-old teaching assistant for wearing a niqab,the Muslim head covering that leaves only the eyes exposed. France has banned the niqab in public schools. In Montreal, a ymca clashes with its Jewish neighbours, members of a Hasidic synagogue; they want the windows of the gym frosted so their worshippers won’t be exposed to the sight of skimpily clad young women mounting the Stairmasters. Elsewhere, some people have petitioned Joan Rivers to take the veil. All over the world, there seems to be confusion about which parts of which women we ought to be able to see.

But Western women have their version of veils as well. Let us project these into the near future and imagine how Islamic cultural scholars might interpret the ruthless orthodoxy of high fashion, the pressure to expose the flesh,and the curious body coverings (and uncoverings) of the secular, middle-class, North American professional woman.

In the evolution of the handbag, it’s not clear when animalskin pouches for carrying personal items began to signal status and self-worth for Western women — the classic Birkin Bag, for example, now starts at $8,000 — but the trend dates back at least three decades. This drift toward handbag extremism has resulted in the Birkinah, a purse that covers the entire female body, with zippered slits for the eyes. Some reformist sects allow narrow leg holes for mobility. When wearing the Birkinah, the woman crosses over from merely possessing (inhavingness) a large purse, with its connotation of wealth and privilege, to actually becoming the living incarnation of a large purse (inbaghavida). (The pejorative term for an adherent of the Birkinah is “bagh lady.”)

Most Birkinahs are made from the skin of animals, with brass or chrome tooling reminiscent of the fins and fenders of early Buicks, once a protective covering for Western men. Upper-class adherents sometimes use motorized carts (birkinabaghnen) to get around; others employ sturdy personal assistants to carry them from place to place. These assistants are known as “my purs-on” (not to be confused with “my people”). However, the overtones of slavery associated with the use of purs-ons has led to a backlash in some areas. And critics say that the high cost of this body covering has created a caste system in the West. (This began long before bags were worn; for years, a woman carrying a Prada tote could enter a room and establish her status over a Guess-bearing woman simply by shifting her bag from one shoulder to another, as in, “She bagged me.”)

Handbags also have a redemptive aspect. After the Bill Clinton sex scandal in the United States, Monica Lewinsky chose to become a designer of handbags in a bid to restore her reputation. (This failed.) Some claim the handbag has military beginnings, in the furry sporran of the Scottish warrior. Others point to the Queen’s handbag: what does it hold? A pleated rain hat and a PowerBar? No one knows, but it is considered an important precursor to the Birkinah.

The inventor of this covering, Sally Rypohl, clearly remembers when the idea of the live-in handbag came to her: “I was trying to walk through the revolving door at Barneys with a large Versace bag over my shoulder when it snagged in the doors. Then I spun around for six or seven minutes before a pedestrian freed me. And as I spun, I had a vision — I saw myself naked, clad only in a kind of leather shroud with a hood. I no longer had to worry about haircuts, manicures, pedicures, my hemline, or my waistline. I could give up Botox, give up Restylane. Now I live inside my bag, protected and anonymous. I can be, quite literally, ‘in’ fashion.”

Although many view the Birkinah as a garment that signifies submissiveness to the whims of fashion, Rypohl claims it is a liberating experience to live free from the scrutiny of men who have been overexposed to Paris Hilton and Scarlett Johansson. The leg holes may restrict circulation, “but they make us look thinner,” claims one happy convert.

Those who have adopted the Birkinah report that they feel “more organized” and “less vulnerable” when wearing their purses. “At social occasions, we can also hang from wall hooks without becoming tired,” one points out. Rather than diminishing their sex appeal, some say the Birkinah actually heightens arousal in their partners. “I find it sexy,” says Luther, husband of Rypohl and a Birkinah booster. “When she’s hidden, I feel safer. And this way, she could be anyone. That’s hot.”

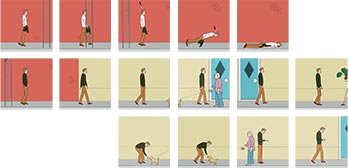

In the wake of the Birkinah, other forms of protective covering for the Western woman have become popular:

A body covering for the active woman, this is an extreme high-top sneaker that extends up to the eyes, with a 146-hole lacing. The unusual feature of this garment is that while women wearing it can walk, run, and use the Stairmaster comfortably, they cannot speak clearly or carry things. “I love wearing the Niqkebab,” says Ellen Rosenquist. “It solves the whole issue of boot-cut versus flared jeans. The only drawback is not being able to hold or bathe my child.”

The Niqkebab has been traced back to the first woman’s running shoe, invented in northern California, when women banded together in a communal effort to lose weight. They stripped tree bark from large sequoia trees, lined it with spongy moss, laced the objects to their feet, and discovered that they could run long distances in this marvellous new footgear. The word “marathon” may have derived from the term “mere-a-thong,” which also came into use at that time.

This is not, strictly speaking, an item of clothing. Followers of this Western body-worshipping sect gather in a kind of mosque known as a “tanning salon,” where they submit to ritual immersion in a reddish-brown pigment that is sprayed under high pressure over the entire body. When the spraying is completed, the woman looks like a piece of fruit leather, and only the eyes and hair are left unveiled. This curious devotion to the carcinogenic “golden body” principle is thought to have arisen shortly after the first waves of European settlers arrived on the coast of Florida and discovered orange juice.

This Western “active wear” with strong links to Eastern religions is worn by urban women who gather in “gyms” to practise yoga or Pilates. Their rituals are often accompanied by recorded chants or music involving Andean pipes. The coverings are monochromatic, highly pliable, and must not be buttoned. Lululem is thought to be the name of a Hawaiian god famous for his flexibility; some gyms display icons of Lululem in a backbend with all his toes in his mouth. Women wearing this garb often carry rolled-up rubber mats on which they kneel during their prayer sessions.

This body covering has polarized women attempting to balance their fashion sense with their mobility, while still maintaining their traditional worship of footwear — a trait shared by women of all sects in the West.

Also known as the “full-body stiletto,” the Blahnikador is an ornate, metre-high, two-legged pedestal, with an open-toe design. This places the woman on a hijanah, or “hopping platform.” Women living on this admittedly stunning platform must nevertheless hoist themselves forward in a lurching gait that has been tagged “nik-nakking.” Critics say the Blahnikador, like the stiletto heel, cruelly limits freedom of movement, but many women defend its use. “We choose the Blahnikador,” they say, “because it fosters privacy, and brings us closer to Heaven.”

Some Western women have gone beyond traditional garments to pursue what they term “visceral veils” — cosmetic procedures that provide a “covering” that can never be removed. Traditional indictors of age and wisdom — lip lines, sagging flesh, imperfections of the skin — are scoured by laser surgery or reinflated by injections of fat from the buttocks. These procedures are collectively known as “the invisceration” — the commitment of the whole body to the principle of hiding or altering the power of the feminine. Numerous groups have spoken out against this practice. “In-viscerents inhibit freedom of expression for the naturally aging female in our society,” claims Cheryl Kapok, spokeswoman for Face It!, an advocacy group that opposes what they call the “surgical burka.”

Many religions around the world have a tradition of covering the head when entering a place of worship. It was only recently, for instance, that Christian women began attending church without wearing a hat. The last vestige of this tradition is the Easter hat. Is this a “nice” version of the crown of thorns? The relationship between the resurrection of Jesus Christ, sealed in a cave, and fanciful spring haberdashery for women has never been fully explained.