“You go—your women stay with me,” the soldier tells my male companions. We’ve been stopped at a checkpoint in the middle of nowhere. I am lying face down in a ditch next to the other female journalist in our convoy, hands behind my head, heart thumping against my flak jacket. Armed soldiers stand over us. We’ve offered to take their photos and tell the world their story, to no avail. They’ve found maps in our car, and—despite the duct-taped letters “TV” on the windshield—they’re accusing us of being spies.

It’s moments like these that make you wonder if reporting from a conflict zone is really such a good idea.

Which is, perhaps, part of the point. Because we’re not actually in a conflict zone yet: we’re in Meaford, Ontario, and the checkpoint soldier (fake Russian accent notwithstanding) is a member of our own Canadian Forces. This is the final morning of the army’s fourday Journalist Familiarization Course. Everyone here is planning—at least at the beginning of the week—to be in Afghanistan within the next few months to cover the 2,500 Canadian troops serving there. The woman lying next to me in the ditch leaves for Kandahar Province tomorrow.

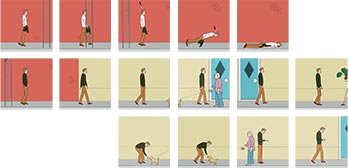

For the past four days, twenty-two of us from across Canada (six provinces and two languages are represented) have lived in barracks and tents, eaten rations and mess-hall meals, and risen at 5 a.m. for lectures and field exercises geared toward preparing us to work in a conflict zone. Our group includes television correspondents, print reporters, camera operators, photographers, and me. My reporting may take me overseas at some point, but right now my interest is in how we get our news—and what that means for the news we get. The practice of embedding journalists—attaching them to a military unit to cover conflict—is highly controversial. Can reporters hope to stay objective while working, living, and experiencing combat with soldiers who might provide them with protection and, of course, who do provide them with access to the stories they are reporting? I’m in Meaford this week to seek answers to such questions.

We never do get through that checkpoint. The men in our group stubbornly refuse to leave us with the soldiers, though they do concede (under pressure) that we are ugly and useless. At the debriefing afterwards, Master Corporal Jeffrey Simmons takes the men to task for this, saying it jeopardizes us all to show disrespect for each other. He suggests that the best approach would have been to negotiate a retreat. Our course leader, Warrant Officer Mark Cushman—a gruff but thoughtful soldier with forearms covered in faded tattoos who has served six tours of duty, including one in Afghanistan—is even more blunt. He says the checkpoint exercise is a leftover from the days of the Bosnian conflict and no longer all that relevant. “Basically if the Taliban get you, there’s no negotiating,” he tells us. “You’ll probably just end up on Al Jazeera.”

An earlier session titled “Surviving Kidnapping and Hostage Taking,” new to the course this year, was more to the point. A forensic psychiatrist and a hostage negotiator covered everything from the best times to attempt escape (while you’re being moved, and only if you know where you are) to proven ways of coping with the boredom of long-term captivity (imagining one of your hobbies, such as building a yacht nail by nail, can help). One of the biggest hazards, they told us, is “McKidnapping”—indiscriminate abductions where the captors sell you to the highest bidder. They cautioned us to make adequate preparations before we go overseas: speak to our families, arrange our wills, purge our laptops, see the dentist, and even bank our dna.

Their slide presentation was laced with disturbing photographs of tortured and decapitated bodies. Experiencing such images was meant to inoculate us against the real thing, but I found it had the opposite effect, making me sick with dread. Others in the group concurred. “I have to admit that Meaford was like a wake-up call,” Marco Fortier of the Journal de Montréal wrote me later. “Becoming fully aware of the mission’s dangers made me think twice about going to Afghanistan. I have two young girls. I want to see them getting older.” Despite his qualms, Fortier says he hopes to deploy this year.

The danger to journalists is very real. At the time of the course, the fighting in southern Afghanistan was at its most intense since 2001, and journalists themselves had become targets. The day I drove to Meaford, the Associated Press quoted a Taliban commander saying, “I want to tell journalists that if in future they use wrong information from coalition forces or nato we will target those journalists and media. We have the Islamic right to kill these journalists and media.” In such a climate, it may be unrealistic to expect many reporters to stray from the relatively protected confines of the Canadian Forces base at Kandahar Airfield.

Despite the current controversy, embedding is nothing new. In previous wars, journalists often wore uniforms and submitted articles to military personnel for vetting before they filed. Since Vietnam, though, there’s been a rise in “unilateral” reporting, which sees journalists work independently of the military. The Balkan conflicts were covered almost entirely by unilaterals, for example, and we’ve come to expect coverage that arises from, and thus reflects, multiple points of view. But the nature of the current conflict in Afghanistan and the targeting of the media have meant that almost all of the journalists reporting from southern Afghanistan are embedded.

The checkpoint exercise was the first in a series intended to test the skills we learned during the week. After the debriefing, we drive on into the wilderness until we are startled by a muted explosion ahead. Rounding a corner, we come upon a smashed-up jeep and “casualties”: a man in uniform wanders aimlessly, speaking nonsense; another is covered in blood, unable to move his leg; one is still in the jeep, white-lipped, clutching his shoulder. I check him for signs of shock. Up close, I can see the tiny feathers of white makeup under his nose. When I steady his arm, bloody entrails pour steaming from his side. I’ve uncovered a hidden, more grievous chest wound (actually raw meat from a nearby slaughterhouse).

The first-aid class we’d taken earlier that week—“Tactical Combat Casualty Care”—was sobering. As we treated each other with objects at hand (a rolledup notebook and a scrunchie make a dandy forearm splint), we were given directives that reflected the shift from peacekeeping to peacemaking in Canada’s mission abroad. In peacekeeping, troops withdraw from the field when they suffer casualties, and medics take over. In peacemaking, though, first aid is geared toward “care under fire”—the bare minimum necessary to maintain life and continue the mission.

Now, as we struggle to get our injured soldier out of the jeep, I’m keenly aware that lessons that seemed straightforward in the classroom are difficult to apply in the field. The eight of us are shouting, arguing about how to treat his wounds. Meanwhile, he appears to lose consciousness. (The acting is first rate, perhaps because Meaford is a training base and the troops are accustomed to war games.) At the debriefing, we ruefully admit that we lost the casualty. In class, Sergeant Malen Vidler told us the forces are no longer taught to “scoop and run,” or retreat with their wounded. “Now we tell them to stay and play”—that is, keep fighting. The implicit message was that journalists should be prepared to administer their own first aid; in combat, they might be a low priority.

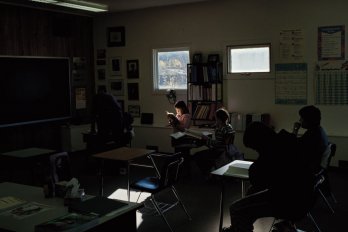

The Canadian program at Kandahar Airfield hosts fifteen journalists at a time, each of whom may stay a maximum of six weeks, and requests to deploy have been growing steadily. For the Canadian Forces, this is embedding on an unprecedented scale. With our troops committed to Afghanistan until 2009, news outlets will have to rotate large numbers of staff through this assignment, and many who will go have had no experience in conflict zones. The fact is that conflicts are no longer covered solely by seasoned war correspondents, but often by reporters who may have little or no experience with the military. In addition to classes like “Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Detection and Survival,” we had “Military Structure and Operations” (which taught us, for instance, to identify rank) and “Weapons of War, Type and Employment” (which included the weapons of the enemy}—lessons that assumed no familiarity with such things.

The military does not require journalists to take this course before arriving, but most news organizations insist on some kind of training, both for the safety of their reporters and to lower the cost of insuring them. The insurance for a reporter in a conflict zone can cost up to $1,000 a day—a huge pressure on the already strained resources of most news organizations.

Each major network and newspaper has at most one correspondent and one photographer or camera operator stationed in Afghanistan, and almost all of those are reporting in the south at Kandahar Airfield. Journalists can leave the base at their own risk, but it is increasingly dangerous to do so. Furthermore, as Christina Stevens—the Global television correspondent beside me in the ditch, who has since returned from a stint in Kandahar—told me, “The networks discourage taking extended trips away from the base, in case there’s breaking news.” The reality is that the media must always be on casualty watch. Unfortunately, at this point little else from Afghanistan is making headlines.

Embedding may be nothing new, but it’s only in the last few years that the military has begun to train the media. Major Peter Sullivan, Deputy Commanding Officer of the Land Force Central Area Training Centre at Meaford, greeted us when we first arrived by saying, “The whole point of having you here is so you come home alive. It’s that simple.” It would be naive, however, to take him at his word. This training also reflects the military’s relatively new, proactive approach to the media—and this is where journalists get uneasy. At the same session, Brigadier General Guy Thibault, Commander of Land Force Central Area, was straightforward about a larger agenda: “This is a very selfish program from my perspective, in the sense that we need something from all of you.”

One thing the military needs is to ensure that reporters do not become a liability to their operations. They encourage journalists to accompany soldiers on patrol, in convoys, and even to field bases when possible. But because of suicide bombers, media are no longer permitted to join a convoy in their own vehicles; now they ride alongside the troops. At the very least, the military has to be confident that reporters and photographers will not interfere with or slow down a mission.

And they need us to be prepared for life on the base, which has its own hazards (the least of which are camel spiders that like to follow in your shadow—those you just kick away). In Meaford, we spent a night in the field, sleeping in rows of cots under a large tent and a black sky. At 2 a.m., we were awakened by ear-splitting explosions and voices shouting, “Stand to! Stand to!” We were under attack. As I fumbled for my glasses and helmet in the wet grass under my cot, half awake, with the searing hiss and bang of smoke bombs falling all around, I could barely recall where the bunker was. Rocket attacks are frequent at Kandahar Airfield. I could have used more practice taking cover.

We also received lessons in convoy discipline, learning how to comport ourselves in light-armoured vehicles (lavs), and how troops would react in case of a strike. We practised donning masks in a hut filled with tear gas; I blew it and had to run outside, eyes streaming and throat burning with the sweet, acrid fumes. We learned how to scan the horizon for suspicious objects; every one of us failed to spot a camouflaged sniper in the tall grass a few metres away. We were even shown how to light a Coleman stove—apparently the best way to make friends in a lav is to start up the coffee while the soldiers secure the area.

Many of our classes served the dual purpose of preparing us for conflict while ensuring that our reporting would be accurate. When we screwed in our earplugs to watch a machine gunner blow a stack of cinder blocks into oblivion, leaving nothing but a small patch of burning grass, it impressed on us both the name of the machine gun (a C6) and the lesson (never take cover behind a cinder-block wall).

We were sometimes a disorderly group, though at the end of the week Captain Julie Misquitta, a public-affairs officer whose friendly, long-lashed eyes belie her toughness, praised our morale and our work overcoming a steep learning curve. One morning we were supposed to be marshalled at 0700 hours, and when some of us arrived a few seconds late Master Corporal Simmons chewed us out, yelling that a convoy would not have waited. But later he apologized, sternly telling us not to take it personally. He was missing the funeral of a fallen soldier and friend that day in Petawawa, and if he was hard on us it was only because “when you fuck up over there, people die.”

Another thing the army hopes this course will do is impress on us what is at stake. The military’s official view of the media has evolved in the past few years from at best tolerance and at worst antagonism to seeing it as “one of the players in the operational sphere,” as Brigadier General Thibault put it. The military has committed itself to not censoring the news unless it compromises operational security (with one exception: in the case of casualties, there is a temporary communications lockdown so families can be notified first). We were told that “the Canadian Forces recognizes your right to information that is unclassified” and that existing rules are “in no way intended to prevent the release of derogatory, embarrassing stories.” In this age of instantaneous communication, such a policy is only pragmatic, Thibault said. “We learned hard lessons in places like Somalia—that we could not in this environment possibly hope to control the information,” he said, and he acknowledged that one negative news item might have a “mission-ending effect.”

Dealing with the media has become part of basic training for soldiers; they now carry a pocket card with tips for handling interviews. Stevens later told me that while there was no vetting of interviews when she was at Kandahar Airfield, officers “watched and listened to and got transcripts of everything that was filed, after it was filed.” Still, embedded reporters are essentially on an honour system, and so far the only punishment for violating the rules has been expulsion from Kandahar Airfield, and only after the story had gone public.

But Thibault wanted something more from the media and he was characteristically direct: “We need you to go in with a sense of what we’re about and trying to accomplish, and of the people who are serving.” He was the Chief of Theatre Information Coordination in Afghanistan between January and August 2004 and he’s well aware that public opinion regarding the nato mission is wavering. Though he assures us he doesn’t want to “use journalists in any untoward way,” he believes the media are “critical for maintaining popular support.” And this is, of course, the crux of it: journalists are rightly wary of delivering propaganda.

The military may no longer try to control the reporting directly, but is something more subtle at play? I must admit that I often found the course disarming. The first morning, they taught us to rappel, first down the side of a low wall and then from a twelve-metre skid. I froze at the top, knees knocking together, but I was coaxed off by the patient, grinning, improbably named Warrant Officer Ken Gallant, who stood opposite me at the top. “Look into my eyes,” he said. “They’ll be the last thing you see.” I gratefully held his gaze as I jumped, and I didn’t get the joke until I landed. At Meaford I also learned this: it’s hard to be objective when you’re hurtling backward through the air. We’d entrusted the soldiers with our safety and in return we’d hoped to impress them with our courage. There was an exhilarating sense that we were all in this together—and it was only nine in the morning on our first day. As we stood around afterwards with our Dixie cups full of watery green refreshment, one reporter remarked that we were quite literally “drinking the Kool-Aid.” I can only imagine how difficult it would be to stay objective if your life actually depended on the soldiers around you.

In the United States, the Pentagon first trained journalists in advance of military action in 2002, provoking howls of outrage. Detractors saw it as a ploy to indoctrinate the media. In an interview with Robin Sloan of Poynter Online, Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent Chris Hedges scoffed at “this whole Boy Scout jamboree experience . . . going down and playing soldier for a week.” But the journalists I met were well aware of the problems inherent in embedding. It was a continual topic of discussion while we learned to prepare and protect ourselves. During the “Surviving Kidnapping” class, the hostage negotiator talked about Stockholm Syndrome—detailing the natural affection that may arise in victims for their captor-hosts—and one reporter wryly compared it to our situation.

I’ve spent the last hour on my belly carefully inching through a “minefield.” Now, as we’re driving back to quarters, I notice a glinting cylinder poking up from the brush. I scream “Gun!” and duck my head between my knees. What happens next is a blur because I never get my head up again. We screech to a halt. There is a lot of yelling in another language. Someone drags me from the car, throws a gunny sack over my head, and binds my hands. I am hustled into a truck, where I sit, trying not to hyperventilate, as it pulls away. I quickly lose track of how many turns we’ve made. I’m surprised at how terrifying this is, even though I know it’s just an exercise. The ties on my wrists are loose but the bag on my head is real.

Warrant Officer Cushman debriefs us afterward, but there’s not a lot to say. Aside from keeping quiet and not resisting, we really had no options. This last exercise merely drives home how vulnerable we would be leaving the base on our own. “Think about that if you are going out without us,” Cushman cautions. We wait for further instructions, but that’s it for the week. “You guys are good to go,” he says. The Journalist Familiarization Course is over.

At the beginning of the week, the brigadier general said to us, “You who will find yourself a part of telling this story will have an important part to play.” Leaving Meaford, I recall his words and wonder if he heard the irony. Becoming part of the story is not how journalists are trained to do their jobs.

We were surrounded at Meaford by first-rate instructors, committed to preparing us to do something they repeatedly told us they would never do: deploy in Afghanistan unarmed. In fact, the openness and the respect we were shown were in and of themselves disarming. Some news outlets prefer to send their reporters on pricier private courses, bypassing the army-sponsored training. But even these journalists will probably end up working side by side with the troops. I wonder whether the public understands, when they see the dateline or hear the sign off from Kandahar Airfield, just how unavoidably symbiotic the reporter’s relationship with the military is. As Christina Stevens said to me, “It’s important to tell the story and it’s too dangerous to do it any other way.” The paradox is this: it has become increasingly difficult for the media to cover the coverage.

Though objectivity is a basic professional requirement for a journalist, there’s no question that reporting is always located in a point of view. The perspective from Kandahar Airfield is certainly a crucial part of the story of Canada’s involvement in Afghanistan, as are the experiences of Canadian soldiers in combat. But there are no doubt important stories evolving beyond the confines of the Canadian bases, and we cannot know what we are missing. We may be missing a great deal