The Québécois filmmaker Claude Jutra, who died twenty years ago in November, made Canada’s most significant contribution to world cinema. He was our great humanist director — our François Truffaut, our Vittorio De Sica, our Satyajit Ray. But unlike these auteurs, he never received much recognition beyond the boundaries of his own country. Even here he was shortchanged, both of the praise he deserved for the best work that followed his masterpiece, the 1971 coming- of-age film Mon oncle Antoine, and, tragically, of the career one would have expected of a man who could produce a picture of such devastating tenderness and robust lyricism.

When Kamouraska, his 1973 followup to Mon oncle Antoine, failed to catch fire even in Quebec and the filmmaking industry stalled there in the midseventies, Jutra accepted an invitation to work at the cbc and moved to Toronto. Cut off from his true creative source, the culture of his home province, his work stagnated. He did make one marvellous sexual comedy in 1981, the spirited, idiosyncratic By Design (which he shot in Vancouver), about a lesbian couple’s efforts to have a child, but with few exceptions it received mean, dismissive reviews. And there were moments in his final feature, La Dame en couleurs, made in Montreal and also about children, which suggested the imaginative spark that had ignited Mon oncle Antoine. But by the time he died, he had long since ceased to be spoken of as a brilliant filmmaker. The sad, lurid details of his death — stricken with early-onset Alzheimer’s he disappeared, and it wasn’t until his body washed up on the banks of the St. Lawrence the following April that suspicions were confirmed that he’d killed himself — upstaged the glory of his artistic achievements.

Any filmmaker who brings to mind De Sica and Ray — not to mention Jean Renoir, whose wide, democratic vision, unmediated compassion, and tonal complexity are obvious touchstones for both Mon oncle Antoine and Kamouraska — must be thought of as classical. But it’s a strange description for Jutra, who had a natural bent for the unorthodox. At eighteen he won a Canadian Film Award for his experimental short, Mouvement perpétuel, an accomplishment that eventually landed him a job at the National Film Board, where he worked on and off from 1953 until the release of Mon oncle Antoine (produced by the nfb). There could probably have been no better training for a burgeoning filmmaker, and Jutra’s mentor was the nfb’s prize animator, Norman McLaren, fabled for his quirkiness and wit. Their 1957 collaboration, the nine-minute short A Chairy Tale, features Jutra himself as a man who must coax a chair into letting him sit down. The film, a comic pas de deux for flesh and wood, suggests both Chagall and Buster Keaton, and you can see how Jutra incorporated the same light, dry humour — whimsy without affectation — in later movies as disparate as his first feature, À tout prendre, and his penultimate fulllength film, By Design.

Jutra worked on a variety of projects for the nfb, in both English and French, some of which are genuine revelations that pointed the way to Mon oncle Antoine. The 1959 Félix Leclerc troubadour, for example, a profile of the Montreal singer set on his farm in snowbound Vaudreuil, contains an unexpected sequence that captures the rural setting in springtime and another shot using lantern light that imagines it as it might have existed in another century. Fanciful as they are, these scenes are rendered in a remarkably free style and they look unlike anything I’ve ever seen in a documentary from this period. Nearly a decade later, after he’d spent time abroad and released À tout prendre, Jutra made The Devil’s Toy for the Film Board. About teenage skateboarders, and shot on the tortuous avenues of Westmount in Montreal, it’s a delirious paean to freedom of movement and a powerful metaphor for freedom of spirit.

Mon oncle Antoine has most often been compared to Truffaut’s The 400 Blows — both portray early-adolescent protagonists contending with the alluring and upsetting realities of the adult world. Indeed, perhaps the most useful way to place Jutra’s aesthetic is within the French New Wave, of which Truffaut and Godard were the most famous proponents. In a sense, Jutra was Canada’s representative member of the New Wave, and his treatment at home, especially with regard to the stunningly underrated Kamouraska, partly reflects Québécois reluctance in the early seventies to see the value in belonging to a movement that was not distinctly theirs. It’s ironic that while European filmmaking helped to bring American movies to a new maturity in the late sixties and early seventies (especially in the work of Robert Altman, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese), in the same era in Quebec, where politics trumped art, the honour of belonging to a world community of great artists had little cachet. Nonetheless, Jutra happily absorbed the influence of Truffaut and Godard, just as earlier he’d worshipped Federico Fellini. Jutra went to France and hung out with the New Wave directors, and travelled to Africa to collaborate with the most unconventional of them, the filmmaker- anthropologist Jean Rouch. When he returned to make his first feature, À tout prendre (1963), he was fully one of their number.

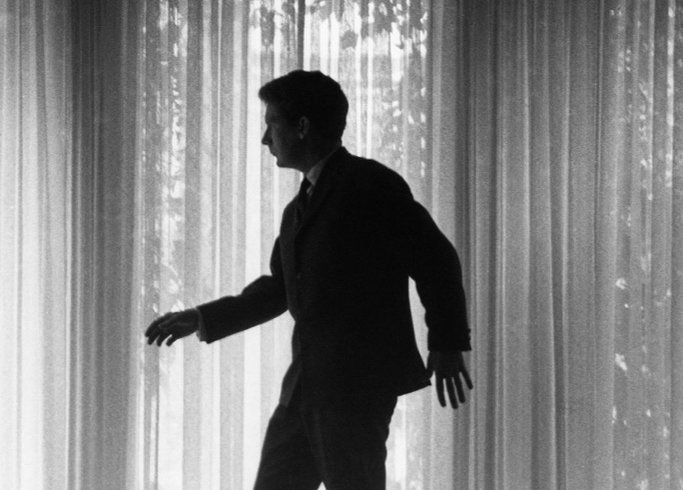

À tout prendre is a kind of diary on film focused on the vicissitudes of a young man’s sexual life. The New Wave’s most fervent Italian counterpart, Bernardo Bertolucci, who was about to make his own autobiographical breakthrough picture, Before the Revolution, adored it, praising Jutra for filming in poetry rather than prose. Jutra’s movie was even more personal than Bertolucci’s: he played the hero, Claude, and cast his friends. À tout prendre transforms youthful bravado and exuberance into lyricism. It draws on the vocabulary of the New Wave — jump cuts, leaping continuity, the playful use of text and soundtrack — and like Breathless or Shoot the Piano Player, it feels utterly unfettered, as if the thoughts and impulses of the filmmaker could be expressed as directly through camera and editing as a writer’s can be through the pen. In one scene, Claude watches, rapt, as a gorgeous black woman sways to the music at a party in someone’s apartment. Her silhouetted image could be the romantic fantasy of every young bachelor, presented in all its imaginative purity.

À tout prendre has more of Godard in it — the Godard not only of Breathless, but of Band of Outsiders and Masculine Feminine, his rites-of-courtship movies — than anything else Jutra made. He’s more firmly in Truffaut territory in Mon oncle Antoine and also in Kamouraska, a film set in 1830s rural Quebec that is akin to Truffaut’s romantic costume drama, The Story of Adèle H. Mon oncle Antoine is a period film, too — it’s based on screenwriter Clément Perron’s reminiscences of his childhood in an asbestos mining town in southwestern Quebec in the late 1940s, and in its depiction of an insular, distinctive, and economically disadvantaged culture it’s comparable to Pather Panchali, the first film in Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy.

But it’s the distinctive Québécois culture that also makes Antoine one of a kind. Jutra wasn’t a political filmmaker, but in its understated way the film addresses the deep-seated tensions between the underpaid French miners and the English bosses. No one who has seen Antoine is likely to have forgotten the scene where the mining boss rides through the streets of the town, scattering holiday trinkets for the children. At first this seems like a magical image, but the context alters it — once again this year the miners have received no Christmas bonus. The adults retreat behind closed doors, torn between their pride and resentment at their employer’s cheap attempt to play the role of benefactor and their reluctance to deny their kids the treats he’s thrown them. The children, sensitive to their parents’ unspoken feelings, are uncertain how to respond. Some of the younger ones run to pick up the presents; others — the teenagers — finger them uneasily. The glittering baubles suddenly look chintzy.

Visually, Jutra builds Mon oncle Antoine on a trio of linked motifs. One is Christmas, presented as simultaneously jubilant and bitter. The protagonist, Benoît, works for his uncle, who runs the town general store and funeral parlour, and while schoolchildren wrestle in the snow and lob snowballs, a crowd gathers outside Antoine’s store for the unveiling of the crèche in the window. On the other hand there is the tight-fisted boss and the Christmas Eve death of a boy for whom Antoine furnishes a coffin, rigging a horse and sleigh to make a late-night call to the boy’s grieving mother with Benoît at his side. She feeds them supper, but Benoît is too unsettled to eat; he’s mesmerized by the slightly open door behind which lurks the corpse of a boy his own age.

In this picture, the secrets of the adult world always hover behind doors left temptingly — or frighteningly — ajar. Benoît watches the local priest steal a swig of sacramental wine, the notary’s buxom wife try on a new girdle in the store, and catches his Aunt Cécile with Antoine’s assistant, Fernand (played by Jutra himself). The third motif involves what the boy sees behind glass, which serves the double purpose of allowing him to peek in and of reminding us of the division between him and whatever he’s watching. The adolescent Benoît is quick to judge the adults for their shortcomings: Antoine for his drunken ineptitude, Cécile and Fernand for their sexual indiscretion.

At the movie’s climax, an inebriated Antoine falls asleep while driving the sleigh bearing the dead boy’s coffin, and Benoît, seizing the reins, embarks on a joyride through the moonlit woods. As in the earlier sleigh scene with the mining boss, the episode begins in enchantment as the horse races through the snow, but the tone shifts as Benoît’s recklessness causes the coffin to slip off onto the snow and his uncle is too drunk to help him retrieve it. By the time Benoît and Fernand return the next day, the mourning family has found the coffin, taken it home, and gathered around it. This time it’s Benoît, standing outside the window, who meets the accusing glare of the dead boy’s mother; it’s he who has committed a sin for which others judge him. Jutra’s combination of sympathy for the boy and unrelenting toughness is, finally, what sets Mon oncle Antoine apart from The 400 Blows, which is bathed in a more sentimental light.

Other facets of the Québécois culture that Jutra renders in such poignant detail in Mon oncle Antoine show up in Kamouraska, his adaptation of Anne Hébert’s bestselling novel. Jutra had his heartaches with the 1973 release of this picture, not only because it didn’t achieve the critical and popular success it deserved, but also because his French producer (it was a co-production of Canada and France) demanded that Jutra edit down to two hours what, with its involved plot and complicated flashback structure, the director had always planned as a three-hour picture. The last-minute cutting worked against him; the 173- minute director’s cut, which he got the opportunity to prepare a decade later, reveals the full weight of the narrative. But even the original version is glorious enough, with its superb performances and its portrait of a repressive society that is both Victorian and Catholic, with sensual impulses that keep bursting through formal surfaces — sometimes comically, sometimes tragically.

Geneviève Bujold plays Elisabeth, who marries the seigneur of Kamouraska, Antoine Tassy, then discovers he’s a moody drunkard and a whoremonger. She begins an affair with an American doctor, George Nelson, who kills Antoine and flees to the United States. She tries to follow him but is detained at the border, sent to trial as an accessory, and finally released for the sake of appearances; she is, after all, an aristocrat. But she never really goes free: she’s incarcerated in the smothering propriety of a loveless second marriage. Hébert’s plot has obvious connections to Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina, while both the male characters — the tormented Antoine and the sexually powerful Nelson, whose passion for Elisabeth is coupled with disgust — remind one of Dostoevsky. But the movie’s delving into the nature of temptation and sin is essentially Catholic, and perhaps no other movie out of Quebec has ever been as daring in its exploration of the effects of French Catholicism on the sexual lives of the characters.

It’s sad that Jutra’s images are now undervalued and hard to access. Mon oncle Antoine is the only one of his features accessible on dvd. The videotapes of À tout prendre and Kamouraska have long been out of print, and they were never available with English subtitles. By Design never, to my knowledge, even came out on tape. It would be a fitting tribute to Canada’s greatest filmmaker if, two decades after his untimely passing, his reputation were restored and his movies returned to the film-loving audience for whom he intended them, and of whom he was himself a vital member.