I. FIRST, CONSIDER YOUR DIRECTIONS

I was given an address for the test kitchen, just over Lions Gate Bridge in North Vancouver, with instructions to enter through the back. There were no instructions about a dusty concrete staircase though, so hesitantly I climbed, emerging in the glass lobby of a law firm. The receptionist told me my address was ten years old, would I please leave. I walked quickly, first along the edge of a small forest, past one back lot and then another. I walked behind a Travelodge, past Denny’s dumpsters, the delivery door for a Vietnamese joint, back and forth, almost an hour lost. My name was shouted. Another lot. Two doors.

And I was inside.

There is nothing remarkable about the Earls Test Kitchen, which is known to insiders as tk1. It is stainless steel and tile, six burners, two long counters, a double fridge, some gadgets. With the door closed it feels like a subway car, its windows revealing the hallway of a much larger kitchen. This larger kitchen opens out to a shiny, boisterous room called Earls Tin Palace, which in turn gives way to the world outside, where fifty-one other Earls are strewn from Fort McMurray almost to the Mexican border. Fifty-three, fifty-four, and fifty-five are on the way.

I have spent my life avoiding Earls. Then Michael Noble started working there.

If you live in the east, you may not know Earls, which surfaced in the west, with oversized papier-mâché parrots dangling from its rafters, about the same time as U2 and Tom Cruise. Earls is known for inventing and reinventing much of our casual-dining canon, most notably the dry rib and the hot chicken Caesar salad. It is known for servers who are not exactly hard on the eyes. It is arguably the safest bet for a first date in the history of dining out. Until recently, a typical Earls was 7,000 square feet and averaged $3 million in annual sales. However, the newest generation of stores have flashier decor and tonier locations like Polo Park in Winnipeg, with sales averaging $5.5 million. One competitor I spoke with equated the Fuller family, which runs Earls and several other high-end chains, to nasa scientists, so systematically have they stayed a teaspoon ahead of the public’s tastes. What they’ve shown in their latest incarnation is that the essential qualities of elite cuisine can be reproduced, packaged, and delivered—without the elitism.

In the autumn of 2004, Michael Noble left Catch, a $5-million fine-dining experiment in downtown Calgary that critics had christened “Canada’s best new restaurant,” to become Earls’ Director of Culinary & Product Development. In the weeks leading up to Christmas, he travelled five times from Calgary to tk1, summoned each time by Earls’ Executive Tasting Panel. On this, his sixth trip, things would get interesting. In a span of thirty hours, he would attempt to crank out ten dishes, representing the final crack at his first full-fledged Earls menu. And then, because this is how the stars sometimes align, he would prepare a single course for La Confrérie de la Chaîne des Rôtisseurs, an international gastronomic society dating back to Louis IX’s Royal Guild of Goose Roasters that is dedicated to safeguarding fine dining as we know it.

Unlike, say, the philharmonic, fine dining has never found itself in special need of safeguarding. But these days, in Europe, Michelin three-star chefs are opening relaxed high-volume “gastro bistros,” while in North America “three-ring binder” chains like Milestone’s, The Keg, and P.F. Chang’s are parlaying their laminated spreadsheets into shares of the casual-gourmet/relaxed-fine-dining niche. Earls’ latest gambit in its ongoing domination of casual gourmet is to infiltrate the Chaîne’s traditional domain by delivering one thing that has always separated authenticity from homogeneity: mystique. Haute cuisine is haute cuisine because of the mystique of its chef.

II. ASSEMBLING YOUR CULINARY MASS-PRODUCTION DEVICE

tk1 has the earthy smell of golden beets, hand-picked for this evening’s Chaîne meal. Two halibut filets, two mahi mahi filets, and two pork chops thaw on the counter for tomorrow’s Executive Tasting Panel. Noble empties two packets of Thai noodles into a pot. As they soak, he opens a can of San Remo white kidney beans. An “automatic towel dispenser buzzes as he washes his hands again and again. “They’re like a tool,” he says. “Keep them clean!” Out in the big kitchen, prep cooks have been at work since 6:30 a.m. “I test and I test,” Noble says as they pass by the window. “I put myself into the headspace of a young guy working at Earls.”

You’re forty-three years old. You spend sixty-plus hours a week inside the relentless whir of a world-class kitchen, more time mentoring misfits with knives than with your own kids. Some guys offer you the chance to work regular hours, you think The hell with it, I’ll start living in the headspace of a sixteen-year-old line cook. While you’re at it, maybe you’ll change some ideas about what a chef is supposed to be.

No device has ever come along that would allow a chef to reach more than a few dozen eaters on any given night. Yes, there are recipe books. Yes, the Food Network has changed what the masses know about eating. But this is not food in your mouth—the evanescent, visceral experience of licking fingerprints off a bone. No one can ship Auguste Escoffier’s “Suprêmes de Poularde aux Ortolans Sarah Bernhardt” halfway across the earth in temperature-controlled Tupperware the way they can an original Vermeer. Until Ferran Adrià figures out how to carpet-bomb Flin Flon, Manitoba, with tiny bubbles of carrot, haute cuisine will be dispatched only one plate at a time. The further cuisine is removed from local ingredients, processes, and theatre, the less profound it seems.

Yet there is an intense desire among the best chefs to be profound right now. Not only are they supposed to be the best chefs, they’re expected to be big-picture icons who change the world. On one extreme, Michael Stadtländer is operating an integrated farm and restaurant in the woods of Ontario—a highly symbolic, gauntlet-throwing project, but at eight-odd diners a night, not especially significant in the grand scheme of how North Americans dine out. On the other extreme, Adrià, who has been called the most imaginative chef in history, recently spent eight months working on a french-fry recipe, the basis for a new fast-food chain intended to recalibrate the way Spanish culture eats, emphasizing flavour, nutrition, value, even wonder.

Right now Noble is closer to the Adrià end of the spectrum. When Earls hired him, he was told two things: Our mission from now on is “to become world famous.” Your job is to create “addictive flavours.” In return, Noble would get reach.

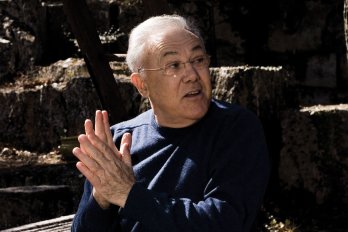

As a member of Canada’s gold-medal-winning team at the 1996 Culinary Olympics in Berlin, as two-time representative at the Bocuse d’Or World Cuisine Contest, and as the only Canadian to compete on the original Iron Chef, Noble has taken his food to scarier juries than Earls’ Executive Tasting Panel. And because he has confronted these juries, because his genius has been hailed in magazines from Gourmet to GQ, because professional chefs talk about him reverently, your fingers might handle the pages of a menu—an Earls menu—with anticipation. Which ones are his But these lifelong operators, who have built an empire on maximizing resources other kitchens haven’t the faintest idea what to do with, still haven’t quite figured this out: how do you harness mystique

To signal Earls’ new direction, their six regional chefs were flown to Vegas, where they dined at Joël Robuchon’s third L’Atelier restaurant (the other two are in Tokyo and Paris). The first thing they ate was chilled avocado foam set atop a brilliant layer of red. “You had to go through the green to get to the mixture below,” Noble says. “It was almost like high-end guacamole and salsa. Still his food. Just more approachable. But still deep.”

When Noble talks about other chefs, he takes on the aura of a character in a Jeunet film—reflective and serene, as though in touch with something very small about the universe’s underlying chemistry. His face is thin and long, as is his body save for his broad shoulders, which can lend his arms and hands the illusion of floating. “I was having dinner there,” he says of L’Atelier, “not because I wanted to dig into the soul of Robuchon, I just wanted to enjoy the food. And then for ten seconds I wondered what he put in there. But then in another ten seconds I wanted another spoonful.” Noble pauses and the hand/shoulder illusion halts. “It sounds egoistic, but I like to think he could have come to one of the great restaurants I worked at and said, “How did he do that’”

Later, we talk about how to codify what, deep down, Noble seems to equate with magic. “Some of the greatest food I’ve ever had in my life you can’t put your finger on it. You can’t go back and recreate it in the kitchen. Cooking’s very personal. There’s no cooking ever done by the book.” But the book is tk1’s raison d’être. Earls puts its finger on it. They rearrange the steps so it can be done by the book. Then they fine-tune the book so that every hapless set of hands at every kitchen in the empire will move as if attached to Noble’s shoulders.

III. WHEN COOKING FOR BIG GROUPS, CATER TO THE MOST SQUEAMISH EATER

Noble works on a lime-green chopping board, cutting and weighing. He fills small baggies and large deli containers with sauces, marinades, pre-packaged chipotle, and cubed ciabatta, dropping near-exact portions on an Accu-Weigh digital scale, tinkering as he goes. Cutting, weighing. Less oil so the chipotle will stick to the pork chop. He works quickly, but whenever he starts to get into a rhythm, the phone rings or a delivery arrives or he must dash out to the main kitchen for a portion of Alfredo. He makes more than twenty-five trips over the course of the morning, excusing himself each time. “Damn, I brought too much,” he says and runs out to return some pre-peeled roasted garlic. Several times, he states he is not used to cooking this way. He glares at a red onion that isn’t up to his standards, then taunts it: “Badass—big, thick, clunky.”

Each recipe in Noble’s blue binder has a title at the top, followed by directions for “finesse.” The finesse for Indonesian Pizza (which will later be renamed Thai Chicken Pizza) reads: “homely natural looking pizza with slightly non-uniform perimeter.” Ingredients and portions are next: “pizza dough,” “Thai peanut sauce,” “nacho cheese portion,” “Indo chicken,” “red onions,” “red peppers,” “roasted pineapple,” “hot banana peppers,” “garnish with a handful of cold Asian salad.” Every element of prep required to assemble this pizza is already required for an existing Earls dish. The aim is not only to leverage the finite range of techniques each kitchen’s line has been rigorously drilled to execute, but also to incorporate every last portion container of nacho cheese and Indo chicken in the joint.

Earls functions not unlike a mirror ball in that it synthesizes cutting-edge trends from around the world and reflects them back in a vernacular of softened angles and flirty girls. When the people who run Earls talk about their “concept,” they inevitably say Yes, but will it fly in Flin Flon There is no Earls in Flin Flon. Not yet. Flin Flon is the great hypothetical test market, shorthand for the question: Can we pump out the exact same bento box we do in Burnaby And more to the point, will Flin Floners buy that bento box if we can

If a dish will eventually fly in Flin Flon, it is because of a plump Ismaili chef with thick black hair named Mo Jessa whose every waking thought is spent disproving the maxim “Too many cooks spoil the broth.” Jessa, who has been with the Fuller family for eighteen years, is an addictive flavour in his own right. His current title is Culinary Concept Leader. It was Jessa who perfected the test kitchen and it is Jessa who painstakingly tweaks Noble’s recipes so they can be crafted chain-wide. As Noble plows through prep for the next morning’s panel, Jessa pops in and out, becoming excited at one point by the shrimp-and-white-bean salad. “There’s a lot of organic in this.”

“The issue last time was lack of zing,” Noble says. “I added cherry vinegar.”

If a dish is accepted by the panel, Jessa’s regional chefs will submit pages of suggestions—they may want to combine steps in the recipe or substitute frozen beans because cans will take too long to open, for example. Jessa ensures that they don’t tweak Noble’s finesse down to nothing. “The white bean salad, it’s going to be difficult to do those Parmesan curls “to order,’” he says. “Somebody’s going to suggest we just put grated Parmesan cheese on it. Michael’s going to have to stand by and say, “No, that’s what makes the salad.’”

Noble and I had discussed originality—how the kernel of a dish enters his mind and leaves through his fingertips, his “addictive flavours” mandate, how there is nothing left to invent. Part of his new job is to eat at the other chains, which are increasingly blurring into an endless, watered-down version of Earls. “They all do ahi tuna with something crunchy,” he says. “Everybody’s copying everybody.”

When Jessa decided to put a single person in tk1, he devised a dream list that included Rob Feenie and Bruno Marti, whom Noble considers his biggest influence. “What sets one chef apart from another” Jessa asks. “It’s like artists. You just look at a painting and go, “That’s it.’” Jessa spends a portion of his work time travelling around North America, attempting to pinpoint markers of craft—how chefs make complex ideas and processes seem effortless. “Whenever we went to Michael’s restaurants, the proteins were perfectly cooked,” he says. “Always. If he sent you a halibut or a steak, you’d look at the way it was cooked and it was always perfect. Very few chefs can do that nine out of ten times, and he can do it every time.”

IV. DEVISE YOUR TWIST!

Among the glut of supplies that turn up over the morning is a Styrofoam chest filled with wild winter salmon, airlifted from Victoria. When Noble pulls back the ice to peek, the deliverer blanches. The filets are neither scaled nor pin-boned—services Noble requested when he placed the order ten days earlier. He shakes his head and mutters, “Should have just got the whole fish.”

The morning’s erratic rhythm is now an eddy. At one point during the next hour of cutting and weighing, he shakes his head in frustration and begins casting glances at a satchel on the right counter. Shortly after noon, the lure becomes too much. The Earls knives go into the dishwasher and a set of Henckels from the 1996 Culinary Olympics is unravelled. He takes some deep breaths, attempting to exit the mind of the line cook. There is, I believe, a moment of doubt.

Using tweezers, he picks each tiny bone out of the salmon. By the time he’s done with this tedious task, another hour is gone and the filets look like a pink, divoted golf course. “Somehow I’ve got to make this shit look presentable by seven tonight,” Noble says. He massages his lower back, fills a portion container with tap water, knocks back two Advils, and pulls out a calculator. A hundred and five guests. Fourteen pieces. Wincing, he says, “They’re going to be all over me tonight.”

Watching him zest lemon into a coarse-salt mix, I catch myself wondering what the big deal is. For two weeks, Noble has been telling me that he doesn’t have his twist—the thing that will make Vancouver Chaîne members say Michael Noble still has it. I ask where the twist will come from. “Some great dishes have come about just opening the fridge and cooking. I’ve got twenty minutes, I’m just sort of feeling it.”

When he dips his hands into the mix—tarragon, star anise, brown sugar, Earls’ Himalayan sea salt—the momentum seems to shift. The smell of licorice rises like rare Dutch candy, the salmon and divots disappear beneath glittering crystal mounds. “I’ll show you how the insta-dicer works,” he suddenly says, beaming. He pulls down what looks like a guillotine from a Ronco infomercial and slams a roasted beet through the grid of blades. One hundred and forty-four perfect quarter-inch cubes shoot out the other end. “I’d never seen an insta-dicer before I got here,” he says, slamming a second beet through. On the third, he exclaims: “Who’s your daddy!” He adds juice from a Japanese citrus fruit called yuzu. Then what looks like a lot of olive oil.

Noble says his parents cooked simply. In grade twelve home ec, he scored ten out of ten on a Belgian waffle assignment. Mrs. Daignault had told him, “When you fold the egg white in, you should still see the droplets.” Because this notion—when you fold the egg white in, you should still see the droplets—seemed kind of far out, he enrolled in culinary school at the Pacific Vocational Institute, then spent three years working at the Hotel Vancouver. At twenty-two, he took a job in Berne, which lasted six months. Another six months in the Canadian Club during Expo ‘86. Eight months at The Loews in Monaco. A stint with Bruno Marti at La Belle Auberge in Ladner, BC. And eight years with the Vancouver Four Seasons. At thirty-four, he opened Diva at the Metropolitan Hotel, “and all of a sudden people knew who the hell I was.”

In all those years, not only had Noble never used an insta-dicer, he had never put lemons in an oven to roast, as he is doing right now—a technique he learned while developing Earls’ mango chutney. When they are finished, he scoops the roasted pulp into a fine sieve and shows me how to massage it through with a spoon. The substance that comes out the other end is delicate and light. He dices the rinds, then some shallots, then mixes both into the substance. Olive oil. Seasoning. I put the tip of the spoon in my mouth. It’s tart and mellow at the same time, the kind of flavour that teaches you about flavour as it is on your tongue. As it inches back in my throat, I say “wow” against my will. The delicate bitterness is replaced by an instant of sweetness. I start to ask Noble how he did that. But I had just seen how.

So instead I ask if this creation qualifies as an addictive flavour. He looks at me, smiles, and says, “You’d never get this at Earls.”

V. DISHING ADVICE

There is a buzz in the kitchen of David Long’s Terminal City Club. Typically, one chef cooks an entire Chaîne meal, but tonight four different chefs are creating four separate courses. Several times I hear the phrase, “Jesus, there’s a lot of talent here.”

Each chef has arrived with at least one assistant, though none of the others are magazine writers. I snip baby celery greens while Noble ambles around the kitchen, teasing cooks he knows from other events, sizing up the ones he has just met. He’s in crisper whites than the Earls coat he wore all day; it takes him half an hour to stop adjusting his chef’s hat. As the evening unfolds and one chef tries to top another, the running gag becomes “Do you do that at Earls” It’s half-hearted, though, a timid way of asking not what’s it like on the dark side, exactly, because Earls isn’t Wal-Mart or McDonald’s, but rather just what side Noble has crossed to.

David Wong, the night’s youngest headliner, peppers Noble with questions about Earls’ winter menu, his tone deferential. “Chef, did you do that chicken sandwich That’s a good sandwich.” He asks about a duck confit pizza, and Noble explains that it didn’t make the final menu. He tells Wong how exciting it was to have taught Earls’ cooks how to braise beef short ribs—a whole new technique for them. They talk about the early days of Diva. Wong asks for feedback on his Chaîne course. And for the first time, I begin to understand a chef’s true capacity for reach. Only a handful of chefs in Canada can claim a tree of protegés as wide and deep as Noble’s. The branches extend into three-star kitchens around the globe; protegés of protegés of protegés are opening restaurants.

Abruptly, Noble’s salmon comes out of the fridge, its ruddiness deepened by the salt. One side is left slightly cured; Wong sears the other. Noble spoons beets, loudly proclaiming, “Look how uniformly cut these are!” There’s a mad rush to arrange 105 plates, which glide out to the dining room on the arms of Terminal City’s bow-tied battalion of servers. The maître d’ rushes into the kitchen and pulls Noble to a podium to explain the course. In contrast to the happy game of kitchen shinny, Terminal City’s banquet room is stiff. Ribbons and medallions dangle from members’ shoulders, designating their place in the hierarchy. There is a smattering of “yaays” and a single very loud “booo” from the right side of the room when Noble is introduced. Catching his breath, he looks around and says, “I’ve been away.” As he describes the pin-boning, the yuzu, the CedarCreek Platinum Reserve Chardonnay (featured on Earls’ wine list) that everyone is now sipping, there is a steady clank of silver on plates. No one appears to be paying attention. Either they’re transfixed by the roasted lemon relish or this is simply how the Chaîne rolls.

VI. TIPS FOR EXPANDING THE PALATE

Comparing notes in tk1 the next morning, I tell Noble that one lady called his salmon “such an Earls dish.” “Who said that” he demands, then grimly concedes, “People think I’ve sold out.” I didn’t tell him that a much older lady had expressed delight that “Michael was preparing a course.” I knew the answer, but asked her anyway: “Have you been down to Hornby Street to try his braised ribs” She blinked a few times, said, “We don’t really eat out that much—,” stopped mid-sentence, then turned and walked away.

As panellists drift past the kitchen door, Noble tries to concentrate on his pasta. Though his affection for Jessa is quite genuine, it’s hard not to detect tension as some others arrive. Notably absent today is Stan Fuller, Earls’ president, but making a surprise appearance, is founder, chair, and family patriarch, Leroy Earl “Bus” Fuller. From day dishwasher to night bartender, one of the first lessons every Earls “partner” must learn is the Bus legend, which begins in a ramshackle restaurant outside Sunburst, Montana. Bus bought the Green & White in 1954, running it between shifts at a Texaco plant. “On the panel, he’s a plain old no-bullshit guy,” Jessa says. “He’ll say “I wouldn’t pay five bucks for that.’” Bus gets the final word on every major Earls decision.

After Bus arrives, a pretty girl with long dark hair starts to hover near the stove. Her name is Mona and she’ll be the panel’s server. She is clearly excited to have been singled out. “This is called “Chick’ Chicken Pasta” she asks Noble.

“Does that offend you”

“No way!”

“It shouldn’t,” one of the line cooks mumbles, “you work at Earls.”

At 9:30 a.m., Mona begins taking out courses—one every fifteen minutes—and the morning quickly becomes a steeplechase. Noble moves between test kitchen and main kitchen—the line, the fryer, the forno wood-burning oven, tinkering until the moment each plate leaves. He puts the finishing touch on a pad Thai, remarking, “There’s no spice that says “pad Thai spice.’ I’m only guessing I’ve got it right.” Around a table on the other side of the restaurant, panellists pick at the bean salad. “Fantastic salad, but is it really better than the spinach salad we have right now”

“Yes. It’s a spring item. I love beans!”

“Good flavour… good cost…”

“But how can you not have a spinach salad on the menu’”

Later Jessa tells me, “I equate it to a war room. What is the strategy Which way do we want to go”

Kim Hirji, whom Noble considers his eyes and ears on the panel, crosses the room, trying not to run. Her voice drops an octave. “It’s good,” she whispers. I ask her what that means. “The salad passed!”

Noble is now a whirl, arranging Baja Fish Tacos, his mouth two-thirds open in concentration, which gives him a Yogi Bear profile. One set of tacos goes out with halibut, the other mahi mahi. I ask which one the panel will prefer.

“Probably halibut.”

“Why”

“That’s the mentality of fish-and-chip eaters the world over.”

He suddenly realizes the tacos have gone without cheese. “Fuck!” he shouts as Mona puts the plates on the table. The tension begins to drain from the morning, until there is only a flat-out rush to plate each item, to get the morning over with.

Hirji returns nervously to the forno, now burning at 577ºF. Instead of pad Thai, the panel wants to go with a green curry from two summers ago. Noble says he can make the green curry better. “Can you do it by Friday” she asks. Once the final contents of the menu are locked in, she’ll have to begin warning suppliers. This morning’s decisions will affect the country’s supply of halibut by 5,500 kilograms per week. Weekly sales of 540-millilitre cans of San Remo white kidney beans will rise by 1,400.

When it’s over, the panellists leave and Noble cleans the test kitchen. The pad Thai sits out in a bowl shaped like Jetsons furniture, barely touched. “Too salty, too fishy,” the panel had said. Also: pad Thai bombed on the menu two years ago, and it is not so easy to make that mirror ball spin in reverse. Noble grabs a handful of cold, clingy noodles and tilts his head. He chews quickly, swallows once. Then quietly but with absolute certainty states: “I like the pad Thai.”

VII. COOKING, EVEN WHEN YOU’RE GONE

At the corner of Smithe and Hornby in downtown Vancouver stands the 9,000-square-foot, $6-million flagship of the chain—the prototype for the next-generation, world-famous Earls. Inside, a delicate staircase divides the dining room from a noisy lounge where plasma screens arc vertically to the ceiling, each set tuned to the same station. When Noble’s long day is over, this is where I go, to try his braised ribs.

Two days earlier, I’d sat along the bar and had noticed a short aboriginal man drinking Kokanee from a bottle, grinning. He too had just arrived in Vancouver—from Flin Flon, of all places. He worked in water treatment and told stories about the experimental marijuana mine. A burger guy, he ate Earls whenever he visited Winnipeg or Vancouver, and he grimaced as I dissected a spire of sesame-seared ahi. I was hoping to see my new friend this evening, to tell him about the last thirty hours. About what I thought it meant.

When I wrote that I’ve spent my life avoiding Earls, that wasn’t entirely true. I am not a snob. A freelance writer does not make enough money to eat snobbishly. Earls was actually my first sushi experience, my first experience with reserve wine, my first time dipping focaccia in olive oil and balsamic vinegar; a place where a couple of relationships began and one graduation was celebrated.

All day in the test kitchen, two adages had mixed in my mind. The first was Brillat-Savarin’s “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are.” I am scared to eat at Earls because I am scared to become what everybody else eats. That goes for all chains, L’Atelier included. Perhaps that’s my loss. Earls serves fresher, more interesting beer than any of the pubs in my neighbourhood. Its Jeera curry has more flavour than the food at the corner tandoori place. Call it bullshit postmodern terroir, but I prefer to take chances on local independents.

Canada’s independent restaurateur of 2003, as chosen by Foodservice and Hospitality magazine, is Stephen Reid. It is Reid who equated the Fullers with nasa scientists, and who initially lured Noble from Vancouver to Calgary to start Catch. Reid’s two-level Wildwood restaurant competes with Earls Tin Palace on Fourth Street in Calgary; the two are next door to one another and do approximately the same annual sales. When Reid speaks about chains, his voice is edged with both ridicule and admiration. “They’ve tried risky flavours and they’ve always come back to safe,” he says. “Safe works.”

I asked Jessa once about Earls’ fundamental homogeneity; his belief in the company’s approach is so deep and honest that it is almost impossible to question. “For a while, I thought that if we were going to have fifty restaurants in fifty neighbourhoods, they should all have their own unique item,” he said. “Shouldn’t we run local Okanagan berries in Kelowna Should we allow the little Edmonton potato company to sell products to the restaurants in Edmonton But you know what, Chris Honestly, I changed my mind after all the experimentation. A good item—that white bean salad with the organic beans and Roma tomatoes—works everywhere.”

The other adage mixing in my mind that afternoon comes from the movie Adaptation: “You are what you love, not what loves you.” After months of relative isolation in tk1 and his Calgary office, straining to achieve reach, Noble has realized that it isn’t enough to merely craft and clone addictive flavours. The last time I met with him, he was planning a trip to Winnipeg to learn the names of the line cooks at the Pembina Highway restaurant, even though he knows they’ll only be there for six months, maybe a year.

Seven years ago in Japan, Hayato Okamitsu watched Noble’s “Battle Potato” against Morimoto on Iron Chef. Then twenty-five, he obtained a working-holiday visa, flew to Vancouver, and persuaded an English-speaking friend to arrange an interview at Diva. After a three-day trial, Noble hired him full-time. “Chef Michael showed me the making of Iron Chef lamb,” Okamitsu said. “Tricky process, but he taught me exactly the same as the TV show. As time went by, he showed me how to make menus, to cost, to be a manager. Meeting him has totally changed my life.” He followed Noble, whom he sometimes calls “Canadian Dad,” to Calgary and was put in charge of Catch’s downstairs oyster bar. When I asked Okamitsu what he thought about people attempting to recreate a Michael Noble dish in fifty-two places at the same time, his eyes turned into saucers and he said, “That’s like some kind of dream world.” Then he told me a story about his idea of reach.

After Noble left Catch, Okamitsu became the chef of the upstairs formal dining room. Last year, his mother passed away, which inspired him to add an item to the menu, “Chika’ Teriyaki Cod, based on a dish she used to make. The listing was accompanied by a three-word description: “Message from Japan.” No test kitchen, no tasting panels. It just went on the menu and instantly became one of the restaurant’s biggest sellers. “I train the young guys to make it. So she’s cooking even though she’s not here.” He paused. Pots and pans clattered in the kitchen. “Her sauce will be alive forever.”