Partly because of empire, all cultures are involved in one another; none is single and pure, all are hybrid, heterogeneous, extraordinarily differentiated, and unmonolithic.

—Edward Said

Culture and Imperialism (1993)

They are saying terrible things about the anthropologist Pierre Maranda in the Solomon Islands.

The accusations began in the heart of the South Pacific archipelago of Melanesia, just off the coast of Malaita, on an artificial island in the middle of the vast Lau Lagoon. They were passed from shore to shore by canoe, skiff, and freight barge, and by 2002 they had made it across the water to Guadalcanal and Honiara, capital of the Solomon Islands.

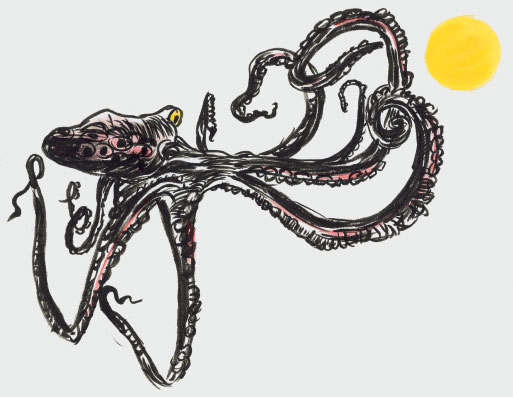

I first heard them from a man with images of the sun—marks of the Lau Lagoon clans—carved into the soft flesh of his cheeks. The man was drunk and possessed by a desperate anger. He insisted that the foreigner had stolen his clan’s octopus and was holding it captive in a swimming pool on his own faraway island, which was called Canada. “And now,” he said, “this Maranda is using the magic power of our octopus to make himself rich and famous.”

To understand this accusation it is helpful to look back to a point near the beginning of time. Some Lau historians remember the beginning this way:

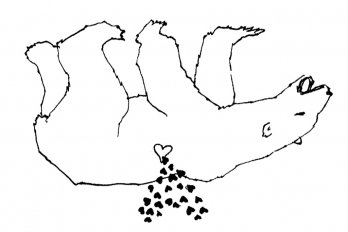

The ancestors, who were descended from worms, lived on a mountain above the jungled folds of Malaita. One day, a hero named Golo’au ventured forth from the mountain to discover the promised land, which was not land at all but a vast, reef-protected lagoon fringing the island’s northwest coast. Golo’au and his kin built rafts from bamboo and they paddled out onto that calm water. They pulled hunks of coral rock from the shallow bottom and piled them upon each other until they had created islands on which they could build thatch houses. The Lau raised their children on the water, safe from the headhunters and mosquitoes that populated the bush. Fish filled their nets. Life was good. When the ancestors died, their spirits did not leave the lagoon. Instead, they inhabited the bodies of sharks and birds and, together with other spirit creatures, they were able to protect their descendants with their magic.

For centuries the Lau people honoured the spirits by following their edicts and killing pigs for them. The priests of the Rere clan offered regular blood sacrifices to the speckled octopus that inhabited the reef near the island of Foueda, ensuring the octopus would protect them from the dangers of the sea. “The octopus took care of people,” the man with the scarified cheeks told me. “If they were lost at sea, he would bring them home. If they were drowning, he would save them.” Sometimes the octopus would crawl right up out of the sea into a priest’s canoe to let him know it was time for a sacrifice. It would crawl onto land, too. If you left a basket of food outside your door, the octopus would plunk himself down on top of it and engulf it. He preferred pork to fruit.

The Rere priests had kept the octopus’s name a secret so that lay people, fools, and enemies could not abuse its power. But, said my friend, all that changed half a lifetime ago. That’s when Maranda tricked the priests into giving him the secret names of their ancestors. He used those words to beguile the octopus, lure it through the reefs and away across the Pacific. The creature did not go willingly. It used its power to strike Maranda with a terrible illness and it killed his wife. But still it did not return. The octopus had not been seen near its coral sanctuary in years. Now, with no spirit to protect them, the people of Foueda have become vulnerable, falling victim to mysterious diseases or drowning inexplicably in the empty and unforgiving sea.

You could call this story a myth, which is to say that historical accuracy is irrelevant to its truths. The archipelago that surrounds the Lau Lagoon has gained a reputation as a veritable Disneyland for anthropologists interested in this kind of narrative. The big guns of early twentieth century anthropology—Bronis?aw Malinowski, W. H. Rivers, Maurice Leenhardt, and others—were convinced by their time in Melanesia that the real function of mythic stories was not to entertain but to serve as vehicles for moral and existential truths. They carried rules for living, values, messages from the ancestors. They told islanders about the most essential parts of themselves. They were metaphors, yes, but they were always sustained by lived experience. And as far as the islanders were concerned, whenever they obeyed the rules set out by their ancestors, they prospered.

But in an era of global cultural convergence, myths can shift as fluidly as the tides that push in and out of the Lau Lagoon. Waves of Christian evangelists have now convinced most Pacific islanders, including the Lau, to trade their guiding myths for those of the Bible. The octopus story—which I heard over and over in the Solomons—signalled a rupture, a brokenness in the spiritual life of the Lau. But nobody was blaming missionaries for the theft of that mythical creature. They were blaming an anthropologist. Who was the foreigner ascribed the role of thief, villain, and myth-breaker, and how had he fallen into this story

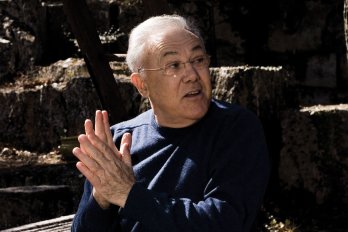

I met Pierre Maranda at Université Laval on a June afternoon nearly two years after first hearing his name. Maranda wanted to show me his backyard. As we roared through Quebec City in his 1982 Turbo Porsche it was hard, at first, to judge the then-seventy-four-year-old anthropologist’s reaction to the strange accusations levelled at him. Not because he was incommunicative, but because his eyes were necessarily hidden behind a pair of wraparound sunglasses. His left cornea had been permanently scarred by the surface glare of the Lau Lagoon.

We reached Maranda’s home in Saint-Nicolas just as the sun was setting. He removed his glasses, squinted out over the St. Lawrence and gestured across his lawn. See No swimming pool. No octopus. He showed his empty yard to the bishop of Malaita on the bishop’s 2004 visit. Maranda wishes all the Lau people could see it.

“It is a very serious charge, that I would be responsible for the collective illness of people I have always loved,” he said, rubbing his scarred eyes wearily. “How could they entertain such thoughts about me”

By some measures, Maranda is eminently qualified to answer that question. As Canada’s leading structural anthropologist, he has spent half a lifetime reducing myths to mathematical algorithms in order to explain their function. But having fallen headlong into the mythology he once studied, Maranda can be forgiven for taking the story personally. Yet to follow Maranda inside his home and through the door guarded by two carved ebony spears is to begin to understand his place in the Lau narrative. Maranda’s study, his sanctuary, is arguably the greatest storehouse of Lau cultural knowledge in the world. The room is cluttered with mahogany ceremonial bowls, charcoal-blackened statues, rough-hewn pigs, and staffs adorned with serpents. One wall is dominated by a black-and-white photo of a naked Lau priest, eyes darkened in a state of ecstasy or possession. The rest are lined with audio tapes and folders jammed with notes on Lau myth, history, riddles, and linguistics. More than 100 musty notebooks contain scribblings from more than 100 Lau hands.

And then there is Maranda himself. The anthropologist probably knows more about Lau history and traditional cosmology than any living person in or out of the lagoon. He is the keeper of secrets and sacred codes that the Lau people believe are the means to control their spirits. He is the link between their past and their future. And so far, he has refused to pass the most sacred of those secrets back to the Lau.

This is Maranda’s version of history:

Having just completed his Ph.D. at Harvard University, he arrived in the Lau Lagoon in 1966 with his wife, Elli Köngäs-Maranda, and their two-year-old son. As researchers at the (now-defunct) Harvard Center for Cognitive Studies, the couple had been captivated by the idea that myths could function as maps for charting the human mind. Maranda could not believe his good fortune when he was dropped on Foueda. He had beat the missionaries. The people rubbed his skin to see if the powder that made him white would rub off. They were not sure if he was a spirit, a ghost, or a man. As he arrived, a small octopus, barely the size of a lobster, rose from the depths of the lagoon and swam to shore. Everyone agreed this was an endorsement from the spirit world.

Maranda learned the Lau language and befriended the pagan priests, particularly those of the powerful Rere clan. It helped that his name echoed that of their holy mountain on Malaita. He gained their trust. Over the following two years, the priests permitted Maranda to observe their rituals and collect their myths. The Lau had a complex and dangerous relationship with the spirit world. Life was governed by strict taboos handed down by the ancestors. Women were associated with the earth and fertility; life-giving power flowed from their vaginas. Men were associated with the sky, and they were careful not to violate the cosmic order by coming into contact with menstrual blood or by placing themselves below a woman’s pelvis. The people built walls in their villages to protect the most sacred aspects of life. Women retreated to their sanctuaries to menstruate and give birth. Male priests made their sacrifices at rock shrines and skull pits in their own enclosures.

The ancestor spirits would not countenance the presence of a foreigner inside the sanctuaries where skulls were kept, but the Lau priests allowed Maranda to fasten his tape recorder to a stick and poke it over the wall when they made their sacrifices. The priests knew full well that Maranda was collecting their secrets.

“They kept telling me: kede, kede, kede: write, write, write!” remembers Maranda. “And at the very end, when we told them we were leaving, the most knowledgeable people came to me and said, “There are things you don’t know, but you must know. All the sacred names of the spirits, all the sacred names of the sanctuaries, extremely secret knowledge, sacred names that empower magical formulas and rituals.’ This information was given to me in a sacred corner of the men’s area. It had to be whispered in my ear, sotto voce.”

The Lau were proud of their culture. They hoped that Maranda would share it with the world. But these secret names were different: they were a means of communicating and controlling the power of the spirits. They were not for sharing. It was as though the priests knew their knowledge was in danger, that their world was about to change, that their secrets needed a guardian.

Maranda returned to the lagoon seven times over the next two decades. With each visit he found the pagan priests more anxious. Seventh-day Adventist missionaries had launched a crusade in the lagoon. The Adventists brought generators and loudspeakers so they could broadcast the Gospel for miles around. They said the spirits” —including the one that resided inside the Foueda octopus—were devils working to trick people on behalf of Satan. The priests told Maranda of the shouting matches they would have with Adventist missionaries on market days. The missionaries would arrive with colourful posters depicting heaven and hell. “If you remain wikita, this is where you will go when you die,” they warned the pagan priests, pointing at the fires of the underworld. “At least we will get to spend eternity with our own ancestors,” the priests would respond.

Christianity had its advantages: The children of Christian converts went to school. They learned to read in English, the new language of commerce and power. Christians didn’t need to spend time and energy raising pigs since the Adventists forbade the consumption of pork, not to mention blood sacrifices. Gradually, people switched allegiances, especially the young. Taboos separating men and women were dropped. The stone walls separating men’s and women’s areas were knocked down.

During a 1975 visit, Maranda was told by Laakwai, a senior Rere priest on Foueda, that the religion of the ancestors was dying. Laakwai could not find a successor, nor could the clan’s other high priest, Kunua. Not even the priests’ sons wanted the sacred knowledge. The young had all turned to the new god. After Maranda left that time, the two priests gave up hope. Laakwai swam under a canoe paddled by a woman, believing that such a reversal of high and low energy would be fatal. Kunua purposefully botched a ritual. Both priests were dead within weeks. It was suicide through metaphysical transgression. The people of Foueda’s primary link to their ancestors had been severed. More and more, they found themselves turning to Christianity.

Meanwhile, at universities in North America and Europe, Maranda used his Lau data as raw material for his academic work, which was profoundly influenced by the pioneering French structuralist, Claude Lévi-Strauss. Lévi-Strauss argued that the most telling aspect of myths was not the unique meaning of words and symbols they contained, but the patterns they formed. He proposed that myths were part of a deep structure of binary opposites that direct how people connote signs and stories. When I reached him by phone at his Paris home, the ninety-seven-year-old Lévi-Strauss said that Maranda has been “paramount” in advancing his structuralist approach, particularly in the algorithmic treatment of anthropological problems.

Maranda’s method links language and stories—like those of the Lau—to the patterned activation of human brain cells. Reduce myth to an equation and you’ve begun to understand the human mind. For his innovative work in artificial intelligence, semantic mapping, and artificial imagination, Maranda was named a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and awarded the prestigious Canada Council Molson Prize in the Social Sciences and Humanities. The Lau storytellers were right: their myths did help propel Maranda to success and international recognition.

For all this, the anthropologist has yet to deconstruct the mechanism by which he has become the villain of the Lau octopus myth. “I have tried to understand how this story came about, who was responsible for it,” he told me. “It must have come through a divining, but who performed it I’ve never been able to get an answer.”

Yet the octopus story does contain elements of historical truth—and evidence of mythical thinking on Maranda’s behalf. Maranda did fall deathly ill a few months after his first stay in the lagoon. (He was diagnosed in Paris with falsiparum, a dangerous strain of malaria. Maranda promptly had money sent to the Solomons to pay the Rere priests for a sacrifice, after which he miraculously recovered.) True to the rumour, Köngäs-Maranda did die. She committed suicide in 1981.

After the suicide of the Rere high priests, Maranda came to be regarded as much more than an observer of Lau culture. During a 2003 stint working for the United Nations in the Solomon Islands, Luc Lafrenière, Maranda’s one-time research assistant, heard Maranda referred to as ngwane foa, a Lau term reserved for high priests. Henry Isa, the Solomon Islands’ chief cultural officer in 2002, put it to me this way: “The Rere clan has only one pagan priest left. That priest is Pierre Maranda.”

Maranda claims not to believe in the supernatural abilities of the Foueda octopus or any other spirit. He insists his faith is reserved for the laws of probability and the cognitive processes by which people constantly recalculate their trust rating for friends, colleagues, and myths. So it is especially curious to see him following a sacred code. Though the Lau Lagoon is a world away from Maranda’s favourite restaurants in Vieux Québec, though he once quite enjoyed the taste of, say, calamari, he now refuses to consume that or any other flesh resembling octopus. Maranda also refuses to reveal the secret name of the Foueda octopus to anyone other than a priestly successor. The man of science is, indeed, behaving as though he were the last of the Rere priests.

An essential element of the octopus myth concerns Maranda’s culpability. Does he deserve to be remembered as the hero or the villain of the story The answer surely depends on his willingness to keep the old knowledge alive—and in Lau hands.

In Melanesia, traditional knowledge has depended increasingly on foreign writers for its survival since the missionaries arrived in the late 1800s. Sometimes islanders forgot their pagan myths after their Christian baptism. Sometimes they censored themselves under pressure from missionaries. These days, some communities trying to revive old traditions have no choice but to turn to written accounts for guidance.

Through their field research, modern anthropologists can become de facto custodians of local knowledge. Most agree that the least they can do for their informants is to give that knowledge back. But repatriating cultural secrets isn’t always so easy. David Akin, an American anthropologist who spent five years among Malaita’s Kwaio people, ran into an unusual roadblock when he tried to send his data back to Malaita. When Akin suggested creating a local cultural archive, at first some pagans were alarmed to hear that Christians might be given access to knowledge about their ancestral religion. It took a decade for those tensions to ease.

Maranda says he is keen to repatriate the bulk of his Lau knowledge, and he has been working since his academic retirement in 1996 to transcribe and catalogue his data. He has led construction of the Cultural Hypermedia Encyclopedia of Oceania (oceanie.org ), a database organized on his theories of semiotic association, and is writing a book on Lau culture. The half-finished manuscript is 600 pages. It would be satisfying to see this as the completion of a circle, the last set of transactions in the series of exchanges that began when Maranda first arrived on Foueda. But it’s one thing to return general knowledge and quite another to pass on powerful secrets. And as one Lau pilgrim learned in 2004, the greatest barrier to returning those secrets—including the name of the Foueda octopus—might well be Maranda himself.

Gabriel Maelasi was born during Maranda’s first sojourn in the Solomons. He carries the ritual scarification marks of the lagoon clans on his face: faint geometric lines, copper rays shooting out from a stylized sun. Like most modern Lau, Maelasi is a passionate Christian. He took the lifelong vows of the Society of St. Francis when he was eighteen. He attended an Anglican theological college on Guadalcanal, and, in 2003, was ordained an Anglican priest on Funafou, a short paddle from Foueda.

But like most islanders, Maelasi maintained a complex and ambiguous relationship with the spirit world. A couple of years ago, when he found the Funafou ancestral skull pits and pagan shrines in disarray, he took it upon himself to tidy up the shrine of one of his own ancestors. An uncle berated him and warned that the spirits would punish him for the offence. Maelasi replied, “No! These people are not strangers. They are part of my community, part of my own blood and bones. I talked to them. I said a prayer to them. You watch and see if I get sick and die for this!”

Maelasi was disturbed by the widening rift he saw growing between his kin and their ancestors. This is one of the reasons he came to Canada in 2004. He understood Maranda’s reputation, and he suspected the anthropologist might possess the means to heal the rift. Maranda took him on as a research assistant, and Maelasi spent the lengthening days of spring transcribing the stories in Maranda’s musty notebooks. It was laborious work, and the books did not contain secrets. But Maelasi did manage to gain entry to Maranda’s Lau sanctuary on the banks of the St. Lawrence.

On his first visit he was awestruck. There was the waist-high statue of Golo’au, his greatest ancestor, whom he remembered as a giant and a headhunter. The statue’s eyes, inlaid with abalone, seemed to stare right into him. And then there was the night in that study when Maranda turned on his computer’s audio player. As the two men gazed into the digital vortex, Maelasi remembers, the grunt and hum of a Lau high priest’s chants filled the room. “Maranda said to me, “Are you possessed by the spirit when you hear that Do you feel that the spirit entangles you’ I said, “No. Oh, no! I’m a normal man, a Christian! I can’t believe in these spirits anymore.’”” To this, Maelasi says his new mentor responded, “But they are powerful, and I respect them.”

Maranda told me the exchange never happened. But seeing them together in Maranda’s sanctuary that spring, Maelasi furiously smoking du Mauriers, Maranda drawing softly on his pipe, was to witness the lagoon’s mythical dilemmas encapsulated. Maelasi let flow the inquiries of theological college. Maranda, to my surprise, lobbied on behalf of the ancestors.

Maelasi told the story of how once, back at college, he and his friends had replaced the imported bread and wine of communion with locally grown taro and coconut milk. Now, to Maranda’s obvious delight, he was pondering the similarities between pagan pig sacrifices and the Christian sacrament. Both rituals promote peace and harmony, and both represent a communion with the spirit world, said Maelasi. “In Malaitan tradition, the pig was our Lamb of God. Pig sacrifice was a saving act for us, in the same way the death of Christ was a saving act. Can I put it like this: Christ is the perfect pig!”

“So instead of saying mass on Funafou, why don’t you sacrifice a pig and hand out the meat as a sacrament to everyone” responded Maranda. “Instead of saying “lamb of God,’ you could say, “pig of God!’””

“I don’t think my bishop would like that at all.”

“But do you think it would make sense”

“When we look at it in a very pure way, yes, the pig is a sacrament,” said Maelasi, shifting in his seat. “But you must have the right theology about it. You must follow the Bible.”

“You have your own Bible! Malaitan custom is full of stories like the ones in the Christian Bible,” said Maranda, who did not take this conversation lightly.

“Gabriel’s ideas are anthropologically sound. They make sense. The pig is a sacrificial animal par excellence,” he said later. “Gabriel is creating a new Melanesian theology.”

Maranda said Maelasi had admitted to him that his guts ached when he heard the old stories, as though he was catching glimpses of his deeper self, a self he was compelled to “rescue and feed.” With that yearning, with his intelligence and charisma, perhaps Maelasi could return to the lagoon as a prophet, delivering a version of Christianity that respected the ancestral spirits, mused Maranda. If that was Maelasi’s intention, if he wanted to push the bounds of religious syncretism and revive the ancestor sacrifices of old, perhaps it would be right to share some of the secret names with him.

“If Gabriel decides that he wants to go and sacrifice pigs and do it in a framework of some kind of syncretic operation, then I could give him at least some of that sacred knowledge. But if the bishop of Malaita chastises him and insists he return to the rank and file of orthodoxy, then I can’t do it.”.”.”. The knowledge is there. It’s ready. It’s available. But I’m not going to disclose it without a proper recipient.”

Maranda insists he is not an interventionist, not for or against the forces of cultural change, which he says are inevitable. But there is more guiding the anthropologist than his theories of probability. Before his time in the lagoons, before his friendship with Lévi-Strauss, Maranda served as a Jesuit priest. He began as a novice at the age of nineteen, and followed the rituals of the Roman Catholic order for a decade. Then one night he dreamt that his brain had been encased in a wire net for all those years. He pulled that net off and felt suddenly free. He left the order and rejected the church.

Maranda acknowledges the peaceable influence Christianity has had in the Solomons. But in his work he consistently portrays Christianized villages as sad places full of listless, unhappy people whose “guts ache—“like Maelasi’s—from spiritual longing. With its emphasis on individualism, he says, Christianity is destroying the co-operative spirit that once bound Lau villagers. In his contribution to The Double Twist, a book he edited in 2001, Maranda used a Lévi-Straussian formula to assert that Malaitan men have used Christianity as a mythical tool to subvert the traditional power of women.

Maranda is as hostile to the church as the old pagan priests of Foueda were. Which is why Maelasi is not the successor Maranda might have hoped for.

Over a beer and a du Maurier at the Laval campus pub, Maelasi told me he had his own plan for Maranda’s secrets. He had already pestered Maranda for the names of the Lau ancestors, but not so he could beg for their magic favour or offer pig sacrifices on their behalf. Quite the opposite. Maelasi’s plan was evangelical. He wanted to identify all the skulls that crowd the shrines of Funafou, so that he could rebaptize them as he had already done for his own namesake. (Mae Laasi, the great fisherman to whom his clan once prayed, was christened Peter, after the Biblical fisher of men.)

“My dream is that we will baptize all these dead skulls,” Maelasi said excitedly. “We will Christianize all the shrines, rebuild them, then plant a cross in front of each one of them, to show that these heathens have now joined the Christian community.” The rift between the Lau and their ancestors would thus be healed, at least in Maelasi’s mind.

Maranda contends that the ancestors would be outraged at the thought of being baptized after their deaths. “They would feel that they had been contaminated, that they will have lost their power.” The plan would effectively paralyze the magic of beings like the sacred octopus, he believes.

Maelasi left Quebec City in 2004, in the depths of winter, having gleaned a few magical incantations but not one of the secret names.

Nearly a year later, I reach Maranda by phone as he is preparing to fly to Paris for a meeting with Lévi-Strauss and then a team of information managers. The Lau data must be digitized, he says; it must be recorded, remembered. This is what anthropologists do.

But to my query about the secret names, he responds that he still hasn’t found the proper recipient. And what if Maelasi was right, I ask, when he suggested that there are no pagans left in the lagoon, that none of the Lau are willing to betray the Christian god for the sake of the ancestors “Then they will never have those names,” Maranda says.

So there is truth to the myth of the stolen octopus, as there is truth in all myth. The Lau are experiencing a spiritual crisis. They have been estranged from their ancestors, and the key to their reconciliation is held by the most jealous of guardians. But their crisis is grounded not so much in thievery as in loyalty. The Lau have pledged their allegiance to a competing god and a new set of myths. And Maranda, faced with a choice between fulfilling the aspirations of the dead or those of a new generation of Lau, has chosen the dead. By holding so rigidly to his promise to the Rere priests, Maranda has become their proxy. He is not an agent of change so much as he is a force for conservatism. Ironically, his intransigence might seal the fate of the Foueda octopus, and the victory of Christianity over the pantheon of ancestor spirits.

The Lau have always believed that the ancestors punish those who do not honour them. Those priests took a chance when they entrusted their knowledge to a foreigner. Would they have wanted the Foueda octopus to be guarded to death Would they have taken such cold revenge on the descendants of worms, of heroes, of island-makers The only answer that matters now is Maranda’s. The storytellers of Foueda may well be right in their assertion that the octopus, or at least its spirit, has left them forever.

As for Maelasi, he has traded the lagoons for the University of Queensland. He is following Maranda’s lead and taking up anthropology, though he still wears his priestly collar.