The bird is hot. That flaxen-hued coin in your pocket is worth more than it has been since it was created in 1987. Economists predict it will fetch ninety cents or more against the US dollar before the end of the year, thanks to high prices for commodities such as gold, natural gas, and, of course, oil.

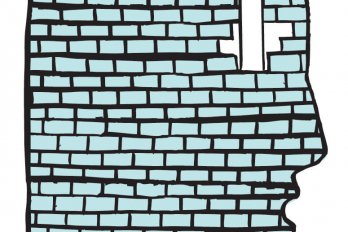

Ironically, Canada’s signature coin is something of an endangered species. In a North American economy forged by silver, the loonie is the last of its breed: a one-dollar coin in wide circulation. But it is losing its lustre, as Canadians increasingly pay for everything from popcorn to parking meters with electronic cash. Canada leads the world in debit-card use, and Dexit, an electronic small-transaction system, arrived in Toronto in late 2003, and now has 50,000 users. As we flock to digital dollars, the loonie may join the joachimsthaler, the Real de a Ocho, and the holey dollar, as part of our country’s currency past.

All sorts of objects were used as currency by primitive economies. Beads, eggs, feathers, ivory, oxen, pigs, rice, salt, and vodka have each been used as money in one place or another. One of the first items to circulate internationally was the cowrie shell, which flowed from the Maldive Islands to wide circulation in West Africa, and to ports as far away as Europe and China.

Precious metals replaced pigs and vodka because they lastedlonger and there was less temptation to consume one’s profits. Silver coins appeared in the Greek city states in about 500 BC; Athens issued one depicting its patron goddess, Athena, on one side and her sacred bird, the owl, on the reverse. These popular tetradrachms, which became known as “owls,” remained in use until the time of Christ. Fowl faded from common currency during the Roman Empire, as emperors preferred coins depicting themselves.

The early sixteenth century saw a major cash crunch. So great was the need for currency that, beginning in about 1519, a Bohemian nobleman began secretly minting silver coins inside his castle. The Holy Roman Empire soon adopted the idea, building a mint in the nearby town of St. Joachimsthal. Its silver coins, which weighed about thirty grams, could soon be found in every corner of Europe.

The Bohemians found it too bothersome to say, “I’ll give you two Joachimsthalers for that cow,” so they called the coins “thalers.” The Dutch called them “daalders,” the Danish “dalers,” and the English “dollars.”

In the New World, Spanish conquistadores found silver deposits dwarfing those near St. Joachimsthal. For the next 300 years, these vast mines supplied an estimated 85 percent of the world’s silver. At Mexico City, Lima, and Potosi (in what is now Bolivia),the Spanish minted a river of real (royal) coins. With galleons freighting Spanish silver throughout the world, the eight-real coin became the first truly global currency. New money punished old businesses, however, and the flood of silver depressed prices throughout Europe, destabilized the Ming Empire, and triggered the decline of great African cities such as Timbuktu.

England took a different tack than Spain, outlawing the minting of currency in its North American colonies. Since many of the pounds and shillings it sent across the Atlantic went right back to England to purchase trade goods, colonists substituted Joachimsthal dollars, French crowns, and Spanish reals. The eight-real silver coin was the most abundant. Mintedby the millions in Mexico, they became known as “pieces of eight” and, because they were almost the same size and weight as the Joachimsthal coins, as “Mexican dollars.” To make change, American colonists would cut the eight-real coins into four wedge-shaped “bits,” each worth a quarter of a dollar. The US adopted the Mexican dollar as its official unit of currency in 1785.

During the early nineteenth century, the monetary system in Upper and Lower Canada was based on British currency,which made for complicationsgiven the shortage of pounds and shillings. In 1813, resourceful colonial authorities in Prince Edward Island punched out the centres of a thousand Mexican silver dollars to make two coins: a donut-shaped “holey dollar” worth five shillings, and the remaining centre plug, worth one shilling.The dollars-to-donuts plan failed within a year, because the coins proved too easy to counterfeit.

The Province of Canada adopted the dollar in 1857, a decision that expanded to the entire Dominion upon Confederation. But with bank notes circulating widely alongside US and Mexican silver dollars, it would take decades for Canada to bother minting its own dollar coin.

In 1935, to commemorate the silver jubilee of King George V’s accession, Toronto sculptor Emanuel Hahn was commissioned to design a silver dollar.

His composition featured a voyageur and an aboriginal paddling a canoe loaded with trade bales—one of which bears the letters HB, for the Hudson’s Bay Company—against a background of northern lights. Hahn’s evocative image endured, remaining on silver (and later nickel) dollar coins until 1987.

During the mid-1980s, Canada decided to switch from paperdollars to coins. Dies for a bronze-plated version of the voyageur coin were cast in Ottawa and prepared for shipment to Winnipeg to be minted in November 1986. But the dies were lost in transit (the story goes that the courier was not asked to show ID) and werenever seen again. Fearing counterfeit, the Royal Canadian Mint readied an alternate design, by Robert-Ralph Carmichael, depicting a loon on the back.

The new coin reached the Canadian public on June 30, 1987. Just as ancient Athenians dubbed their common coin the “owl,” Canadians began calling their new dollar the “loonie.” Whether future civilizations will conclude that the loon was the Queen’s sacred bird remains to be seen.