london—Even by the rarefied standards of fine wine-making, Château Pétrus takes extraordinary care with its grapes. A small estate in the Pomerol region of France, with a mere twenty-eight acres producing fewer than 4,000 cases a year, Pétrus pampers its grapes “like children” and picks only in the afternoon so as not to risk the slightest dilution by the morning dew. To prevent the wine from losing any of its richness, it is never filtered. Instead, five fresh egg whites are added to each oak barrel for clarification. The result is the equivalent of a premier grand cru, or first great growth, of a top-quality Bordeaux.

It is also one of the most sought-after wines among London’s moneyed set. The great châteaux of the Bordeaux—Lafite-Rothschild, Latour, Margaux, Mouton-Rothschild, and Haut-Brion—may have more history, but buyers can’t seem to get enough of Pétrus Pomerol and they are willing to pay almost any amount for the privilege of quaffing down a ruby-black richness that one critic calls “more blood than booze.”

Six now-legendary investment bankers from Barclays Capital took this wine lust to unprecedented heights in 2001 when they lashed out $110,000 for one lunch. Most of their bill went toward three bottles of wine—a 1947 Pétrus Pomerol for $30,750, a 1945 Pétrus Pomerol for $29,000, and a 1946 Pétrus Pomerol for $23,500. Their bacchanalian spree amounted to about $550 a swallow.

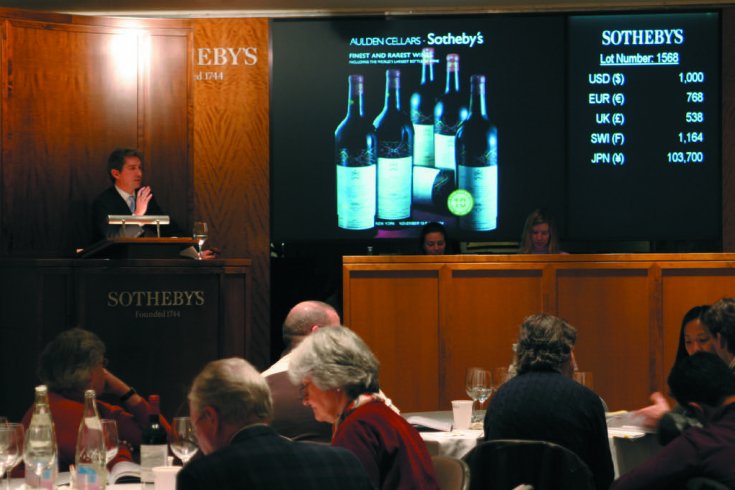

If the temptation to drink them can be resisted, such fine wines amount to liquid real estate. The value of all 1990 vintage grands crus Bordeaux rose 500 percent by 2000, a greater rate of increase than most property or antiques. Sotheby’s was the first of the great auction houses to begin selling fine wines, in 1994. When the Earl of Spencer, the brother of Diana, Princess of Wales, decided to sell off 105 cases of fine champagne, claret, Madeira, and port last year, he took the lot to Sotheby’s. The sale realized $253,000, including $2,250 for a bottle of champagne from his sister’s 1981 wedding to the Prince of Wales.

In all, Sotheby’s shifted $28.5 million worth of wine last year, the highest priced being twelve bottles of Château Cheval Blanc 1947, which sold for a total of $104,250. Once the preserve of traders and restaurateurs, the Sotheby’s wine auctions have increasingly become the playground of personal shoppers; of the ten most expensive lots sold in 2004, eight of them went to private cellars.

To Sotheby’s then, to see what bargains can be had. The people in attendance are dressed with the understated elegance that identifies London’s privileged set, although a few display extravagant flourishes—thigh-high Miuccia Prada boots, luxuriant pashmina scarves, Hermès Birkin handbags. One elderly gentleman is sporting a panama hat, from James Lock & Co., on St. James’s Street. (Madonna has the same hat, and the style is unmistakable.) If the buyer’s attention wanders, there are a number of distractions. Paintings from an upcoming exhibit of Irish artists are hanging beneath two massive Irish elk horns that are almost 13,000 years old and are expected to fetch $150,000 apiece.

The institutional buyers, it seems, have all pre-registered their bids or are bidding over the telephone. Their paddle numbers are quickly memorized—1059 is buying for the merchant trade, while 1070 is buying cases suitable for a restaurant cellar. The first six cases of Château Latour 1961 are purchased by telephone bidders, who pay between $40,250 and $54,625 a case. Bidding on the seventh lot of the same wine, in six magnum bottles, opens at $40,000, which is quickly raised by a man seated behind me to $45,000 ($51,750 if you include the auctioneer’s commission). The successful bidder is about thirty-five years old, dark and handsome, in a navy pinstripe suit. He has paid the equivalent of $4,300 a bottle, and I later learn that he is buying on behalf of an Asian collector.

Fewer than two dozen buyers appear in person, and many of these have their eyes on particular lots. A lanky man in blue jeans is seated beside Miss Prada Boots, and, though it may be my imagination, he rises to leave after purchasing only enough wine to impress her. A young, well-dressed Japanese woman to my right is taking orders in a flustered manner over her phone from some superior.

I am waiting for the star Pétrus of the morning sale, a lot of ten bottles of Château Pétrus 1999, still young and relatively cheap (for now). The sales catalogue gushes over this wine: “Scented, aromatic, redcurrant nose. There is a touch of beautiful oak on the palate, with masses of come-hither fruit. Seamless and silky. Just so well bred—like the racehorses Christian Moueix likes so much!” Christian Moueix is the son of the vineyard’s owner, but I’m not sure if that qualifies his horses as something I would want to have flavour my wine.

The bidding opens at $5,250 a case, and within seconds a buyer who had been quietly biding his time trounces all with a bid of $6,000. Including the premium, that’s $6,900, or nearly $700 a bottle. There is an aphorism among wine lovers that a $70 bottle of wine tastes more than ten times as good as a $7 bottle of wine. I am left wondering what a $700 bottle of wine tastes like.