“In Hungary, when I was a child, the women in almost every household embroidered. They embellished objects for everyday use. I did it reluctantly; I wanted to be out playing. I have very fond memories of the process, though – the mood on a quiet afternoon, usually after very hard work in the fields. It was nice to sit with clean hands and in better clothes, and stitch.

“At art school I specialized in print design, but after my first son was born I realized I needed to change the way I worked. I remembered how my mother and grandmother did their embroidery when they had bits of spare time. So the ancient patterns suddenly and unexpectedly surfaced.

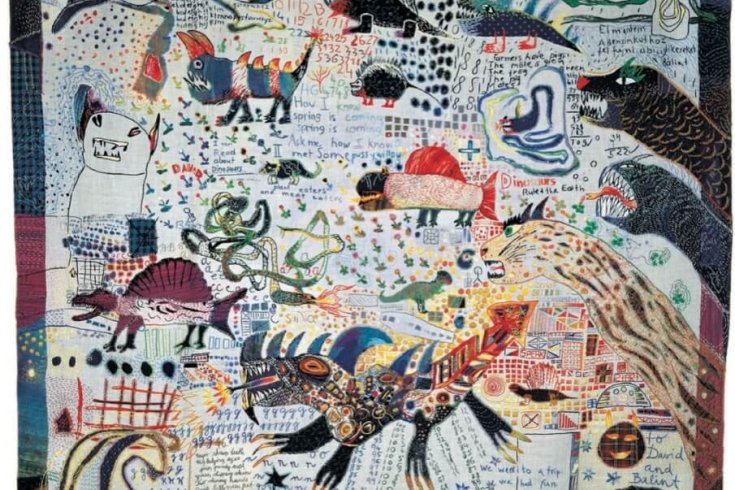

“This piece [‘Bestiary III’] is one of three in a series. Abestiary is a catalogue of beasts. The idea dates back to the ancient Greeks: they classified living creatures, but they gave equal rank to mythical creatures too. I compared this to my children’s early drawings that exhibited real animals – dogs, cows – along with their own creations. Their imagined creatures were so much like the mythological creatures in a bestiary.

“My children are now grown. I use their decaying childhood drawings because I want to steal the intensity behind them. They drew quickly and powerfully. Embroidery is very much the opposite of that way of working. But I wanted to make something powerful, not just decadent and pretty. Children draw because the desire is there. With embroidery, I can save the desire in this format; it’s forever.

“Now I work on my art full-time. One piece takes me about two months of working forty or fifty hours a week. First I equal rank to mythical creatures too. I compared this to my children’s early drawings that exhibited real animals – dogs, cows – along with their own creations. Their imagined creatures were so much like the mythological creatures in a bestiary. “My children are now grown. I use their decaying child-hood drawings because I want to steal the intensity behind them. They drew quickly and powerfully. Embroidery is very much the opposite of that way of working. But I wanted to make something powerful, not just decadent and pretty. Children draw because the desire is there. With embroidery, I can save the desire in this format; it’s forever. “Now I work on my art full-time. One piece takes me about two months of working forty or fifty hours a week. First I imagine it – the colour, everything – and collect fibres and drawings. I do research at the library. When I feel I’m ready, I begin sketching. It doesn’t always come easily. I start filling the tracing paper with black-and-white drawings, and when I’m satisfied with that skeleton, I trace it onto the fabric. Then I sit down and begin to work. It’s a painstaking task, but I remind myself how beautiful it will be when I’m finished.

“This work is layered with culture. Stories in pictures can be found around the globe because every culture tries to explain things in this way. When I do a piece, I know there are many generations behind me. The work is very sensuous. When I touch silk, I think: ‘Ohh, it came from China, and they raised the silk worms; it was probably a family business.’ There are endless stories in a little piece of fabric.”