antwerp—This ancient port city is home to nearly half of Belgium’s estimated 40,000 Jews, whose roots here reach back to the thirteenth century. At the city’s centre are the jeweller stores and gem traders that cluster the entire length of Antwerp’s cavernous Central Station, the heart of a centuries-old diamond business. Ultra-Orthodox Hasidim frequently cycle by or stop to chat in Yiddish, while women wrapped in head scarves gaze into kosher storefronts. There is wealth here, but also privation.

On the other side of the station, to the right of the tracks, a wide highway carves into an area known as Borgerhout. It might as well be a different world. Narrow streets snake away from this central road; tower blocks thrust into the winter sky. Home to 30,000 mainly Moroccan immigrants, it is a place of poverty and frustration. And now increasing disaffection has led the young of this community to lash out.

In the public mind in Belgium, as in other parts of Europe, young Muslims have been linked to rising crime and drug abuse, and castigated for reliance on state handouts. In Antwerp, Moroccans in particular are blamed for “failing to integrate.” The youths themselves describe rampant discrimination and police brutality. Many young Muslims have turned to the Arab European League (AEL), a controversial group that calls for the recognition of Arabic as one of Belgium’s official languages, for Arab unity on Palestine, and for resistance to integration. AEL members were involved in violent protests last spring. A synagogue was firebombed and cars and shop windows in the Jewish quarter vandalized.

Jewish leaders have complained that anti-Semitism is on the rise: up to one incident a week in Antwerp after 9/11. In May, 2002, a father and son were beaten and kicked by a group of Moroccan youths who shouted Nazi slogans. Acts of vandalism have also been reported against Jewish clubs and organizations. “There was always a sleeping anti-Semitism,” says Eli Ringer, a secular Jew and president of Belgium’s Forum of Jewish Organizations, “but the situation in the Middle East is being exported here and a lot of Arab youngsters are openly anti-Semitic.”

The anger and frustration within the Jewish community has been exacerbated by growing criticism of Israel in the Belgian media and in parliament. There have even been attempts by Palestinian survivors of the Sabra and Shatila massacres in Lebanon to indict Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon for war crimes under Belgium’s “universal jurisdiction law.” More surprising, though, is the fact that some Jewish voters are looking to one of the continent’s most radical far-right parties – the Vlaams Blok (Flemish Blok) – for a solution. As recently as the early nineties, the Blok was railing against a “Jewish plot against Europe.”

Founded in 1977, the Blok’s leaders have included former SS members and Holocaust deniers. One of the fastest-growing far-right parties in Europe, it calls for the deportation of “non-assimilating” foreigners and promotes authoritarian law and order policies. And – as if to prove the adage about strange bedfellows – the Vlaams Blok has now declared its support for the plight of Belgium’s Jews.

On an otherwise quiet Tuesday evening, I made my way to a large community hall on the edge of the Jewish quarter. A soft rain was falling on the cobbled streets and the passing trams. Even before I entered the hot building, I could hear chanting: “Eigen volk eerst! Eigen volk eerst!” (“Our own people first! Our own people first!”) Inside, the roar from the crowd of several thousand mostly middle-aged men and women was deafening. Stirring music from The Lord of the Rings film score thundered from the sound system. The mood was infectious and unsettling.

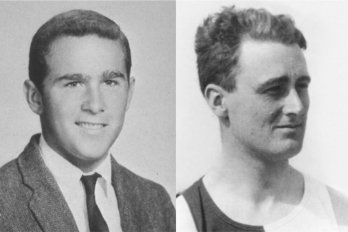

The Vlaams Blok’s youthful Antwerp leader, the smiling Filip Dewinter, increased the tempo and told his audience that there must be no right to vote for foreigners. Beside him on the stage sat representatives from the anti-immigrant Northern League of Italy, Le Pen’s Front National of France, and the late Pim Fortuyn’s party in Holland. Each in turn took the podium, whipping up the audience with scare stories of immigration, crime, Islam, and the imminent opening of a “Pandora’s Box” of troubles.

Despite the controversy, the Vlaams Blok took almost 20 percent of the Flemish vote in last May’s national elections, to add to the one-third of municipal seats it already held in Antwerp. In doing so, it has made its mark as the main party of protest. Now it’s striving for more political power.

To that end, the Blok has reached out to the Hasidic community in particular, both through mass mailings and by speaking out on issues affecting Jews. It vehemently opposed the prosecution of Sharon. Hilde De Lobel, leader of the Blok’s Antwerp councillors, is demanding the expulsion of the AEL’s controversial leader, Dyab Abou Jahjah. Its message has been simple: If you vote for us, we will protect you.

Sitting in his office the day after the Vlaams Blok’s rally – just a few hundred metres from where it took place – Dr. Henri Rosenberg confirmed that such harassment, coupled with the Blok’s message, has pushed some Jews to support the party. As an Orthodox Jew and Europe’s only rabbinical lawyer, he argues that the traditional parties’ “stance against Israel” (Yasser Arafat was invited to speak in the Belgian parliament; Sharon was barred) have definitely contributed to the current situation. “You also have opinion-makers in the Orthodox community openly advocating for the Vlaams Blok,” he adds.

Professor Vivian Liska, director of Antwerp’s Institute of Jewish Studies, is one of the Blok’s vocal critics. She calls the Jewish support of the party dangerous and unethical. “There might be pragmatic reasons [for doing so],” she says, “but this disregards what the Blok would do if Jews were the only foreigners.”

No one knows yet just how many Jews have been seduced by the Blok’s message: the Hasidim do not participate in opinion polls and the results of the most recent elections have not been broken down by neighbourhood. Community leaders remain reluctant to talk. But the effectiveness of the Vlaams Blok’s strategy may soon become apparent. European Union and regional elections will be held this spring.

For now, the tension simmers.