AFTER a screening of the rough cut of Shrek a few years ago, it was decided there was a problem with the film’s title character, a lonely ogre played by Mike Myers. The problem wasn’t the dialogue or the animation; it was the accent. Myers, a native of Toronto, had delivered his lines in his regular voice, making the creature a southern Ontario ogre. That just wasn’t funny.

Myers decided to re-dub the part in a Scottish brogue that reminded him of the voices his own mother, who was English, used when she read fairy tales to her children. Crowds roared at the Scottish Shrek and were forgiving of instances where the actor, according to at least one critic, lapsed into Canadian.

There are those who might take umbrage at being told their accent isn’t worthy of an animated green monster. Canadians are more likely to be grateful that Mike Myers’s linguistic passport was read at all. The Canadian dialect is so subtle it is routinely mistaken as non-existent, or at least as indistinguishable from generic American.

Dialects, of course, are comprised equally of accent and idioms. There isn’t a uniform Canadian accent, just as there isn’t a uniform British, or American, or Indian, accent. But there are definite characteristics to Canadian speech, and they show very little variation from the Ottawa River to the Pacific. Generally, Mainland Canadian speech is most similar to the speech of the American West. Our speech is clipped and evenly cadenced. Linguists also write about the phenomenon of “Canadian raising,” whereby the initial vowel element in certain vowel clusters is spoken higher in the mouth than in American versions, with a shorter glide to the second element. We say “couch” with an “ouch” and our “house” sounds like “lout,” rather than “loud.” We are rumoured to say “ah-boot” for “about,” though that may simply be how others hear these high and fast diphthongs.

According to Henry Rogers, a linguist at the University of Toronto, the Canadian accent is actually moving further away from the American. “Something called the Northern Cities Vowel Shift is taking place in the U.S.,” he says. “Vowels are sort of shifting in one direction, whereas in Canada they’re shifting in the other direction.” And there are linguists, at the McGill Dialectology and Sociolinguistics Lab, for instance, who study regional variation in pronunciation within Canadian speech.

Still, not all experts are convinced that Canadian English is faring well. There are academic papers charting its disappearance. A few hard-headed linguists even declare the very notion of a Canadian dialect a myth, fabricated to bolster a wobbly national identity.

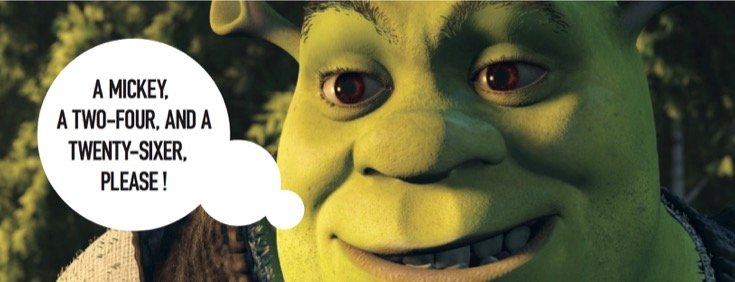

As for the other component of dialect, there is evidence of distinctly Canadian expressions. The most recent Collins English Dictionary includes some 150 new “Canadian” terms. “Status Indian” and “equalization payment” probably won’t excite linguistic pride. But a “saw-off,” for a compromise, and “idiot strings,” for the ties that keep children’s mittens attached to their coats, are lively enough. Then there are our drinking words: a “two-four” and a “twenty-sixer” and a “mickey” of rye, the latter often sipped out of a brown paper bag.

That said, Canadian English, at least from Ottawa westward, can’t come close to Irish or Australian for wit and inventiveness. It can’t even rival the other major Canadian dialect, the one belonging to Newfoundland. Some of this, according to Charles Boberg, the director of the McGill dialectology lab, has to do with dialect variation. “Old, densely populated areas like England or the eastern U.S. have a lot of dialect variation,” he says. “More recently and sparsely settled regions, like Western Canada and the Western U.S., exhibit more homogeneity over large areas.”

We drift toward the pronunciation that surrounds us, and cities, where most Canadians now live, aren’t necessarily the best places to preserve existing accents, or acquire new ones.

On Canada’s East Coast, on the other hand, geographical isolation, along with deep Scottish and Irish roots, ensured that the pronunciation would remain distinct from that of the more heterogeneous middle of the country. There are entire dictionaries that catalogue the vocabularies of Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton and South Shore. And out on the Rock, the speech remains musical and loose and nicely barbed.

An off-the-cuff remark by the New-foundland comedian Mary Walsh, who declared someone to be “still having the mark of the bucket on her arse,” started the television critic John Doyle wondering how she gets away with it. Doyle, who recalled the insult from his own Irish childhood, concluded that the line would have been unacceptable on Canadian TV “if it had been delivered in less colourful language, and without the accent.”

The question is, do most Canadians want to leave such a strong impression? The linguistic impulses of most of the English-speaking nation have tended toward moderation and, sometimes, disguise. Generations of Canadian actors and newsreaders have counted on both to launch careers in the States.

There could also be a class dimension to how the majority of us talk. Middle-class, urban societies tend to avoid strong or idiosyncratic speech, finding such verbal energy unruly. For all their appeal, regional idioms, especially those from the historically poorer “Celtic” regions of Canada, with their culturally ingrained admiration of wordplay and irreverence, have made scant impact on the wider nation. Most of the country hasn’t taken into its collective mouth “having a scoff” for eating a meal, or being “stogged” for being stuffed up; it doesn’t declare, about blackflies, “If you kill one, fifty more come to its funeral.” Few Manitobans, say, delight in explaining that “scluttery” means fatty, or that a guy who has “chowdered it” has messed something up.

If we did, perhaps Mike Myers would have stayed with his Canadian accent. Shrek, after all, would have made a fine Newfoundland ogre.