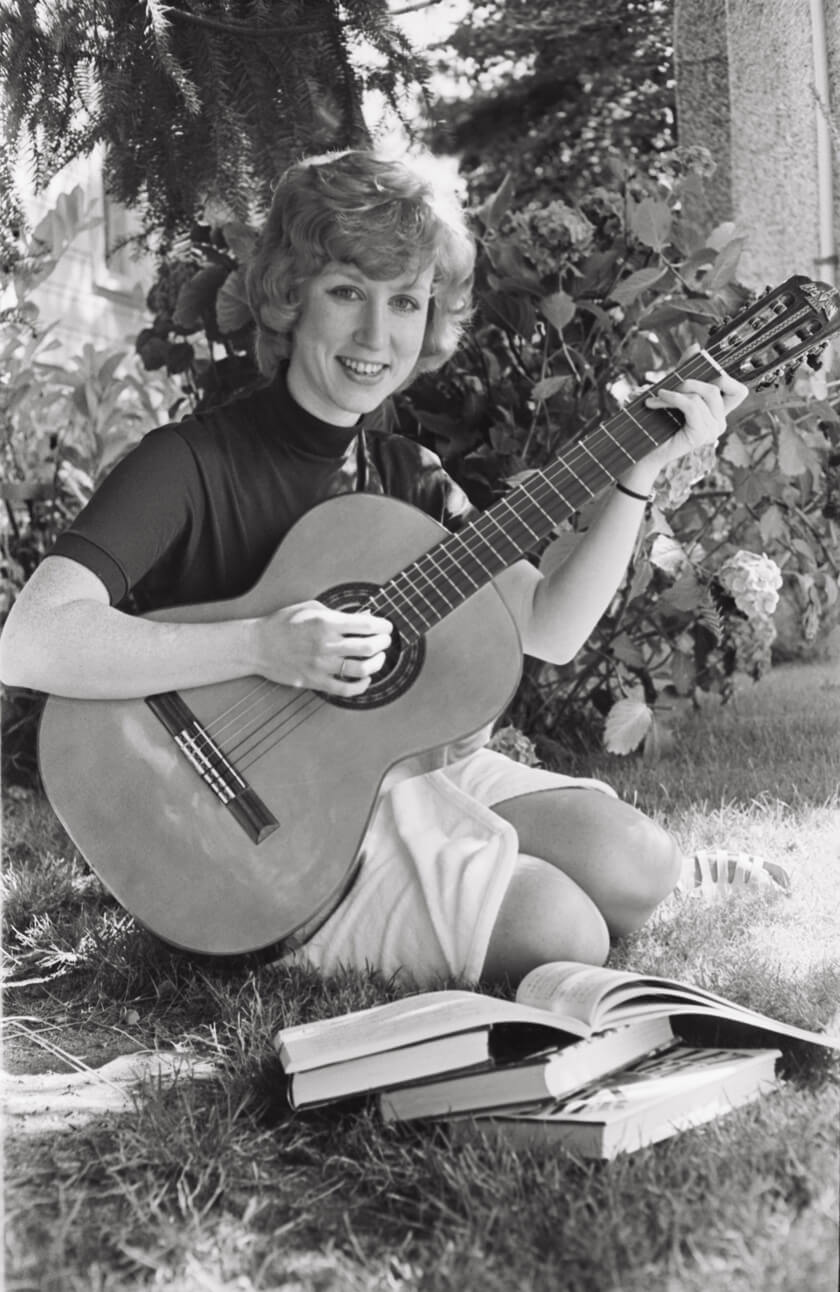

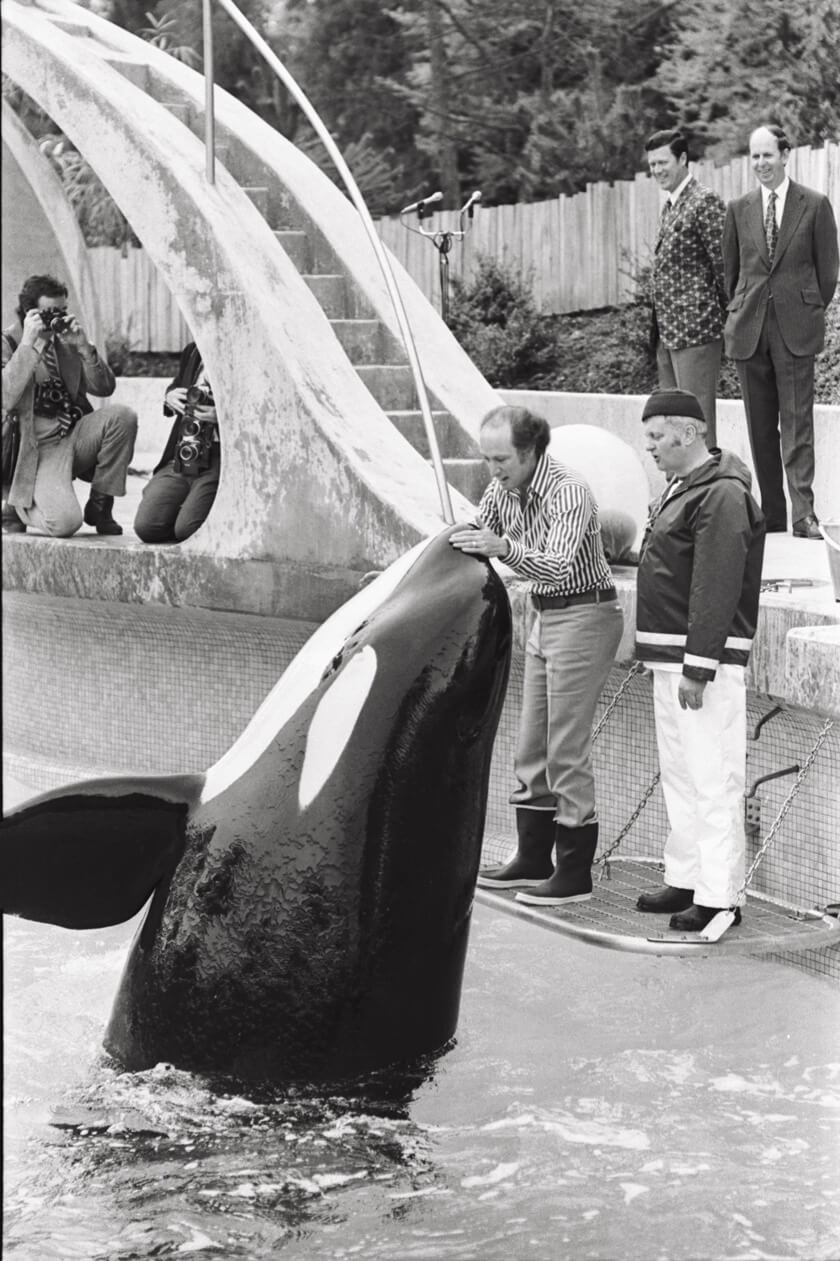

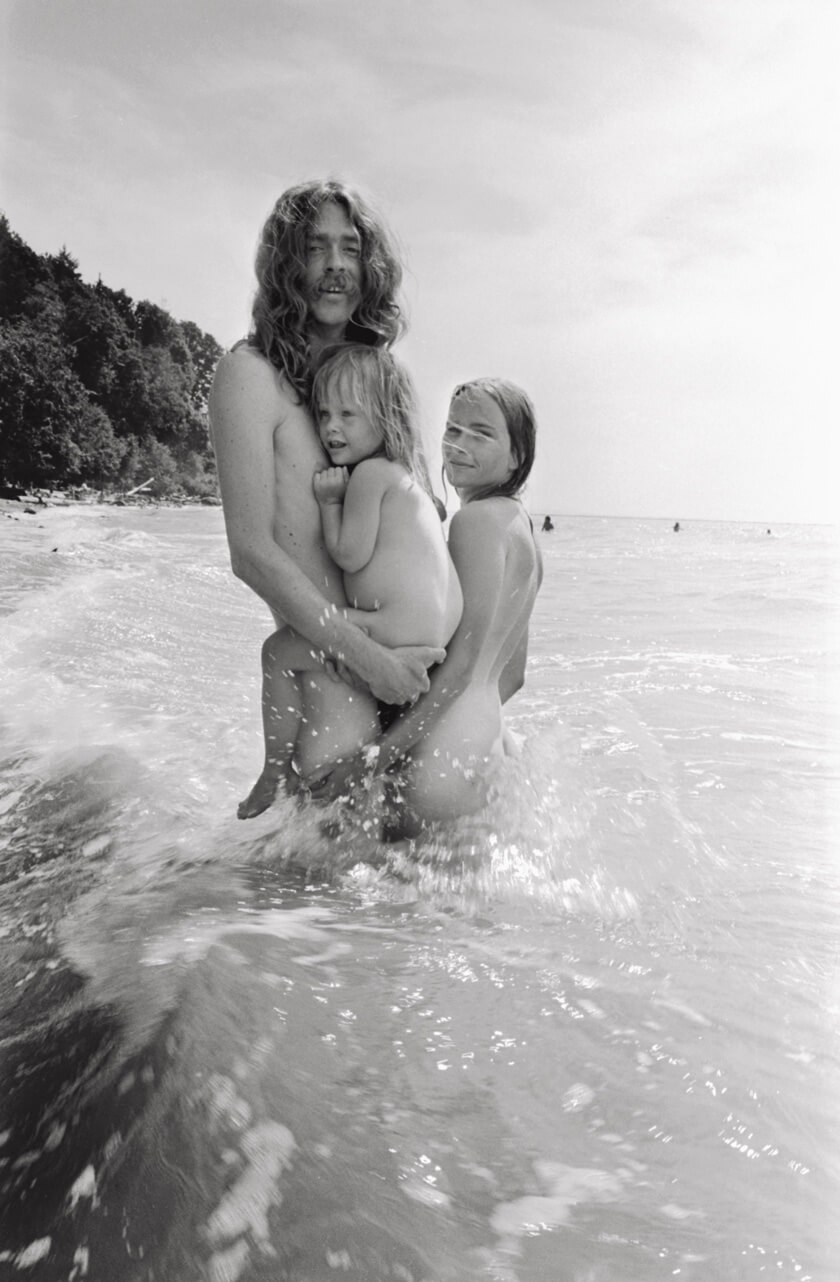

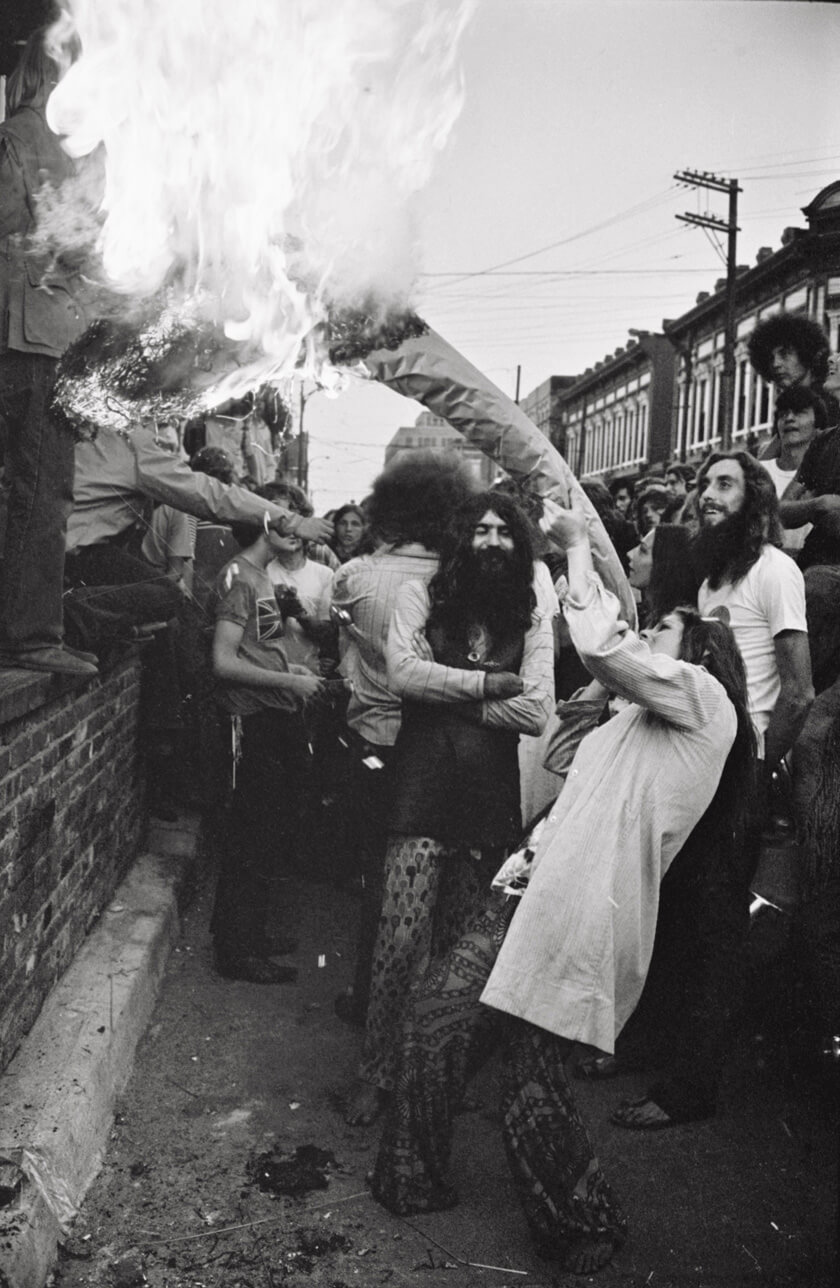

It could be a photograph of the premier of BC on election night, triumphant in victory. Or joyful children on the playground of an inner-city school. It might be an image of defiant inmates behind prison bars, or farm workers relaxing on a lunch break. All are photojournalism. Images of people and events, historic or ordinary, that tell a story.

In the 1970s, Vancouver Sun photographers captured the changing city through more than 4,500 assignments each year, covering news, politics, business and industry, sports, food and fashion, and a host of local events, all on deadline. Photographers were also assigned “tour” shots by former head photographer Charlie Warner. As long-time Sun photographer Ralph Bower recalled in an article, “You just went out the door and found pictures.”

Some completed assignments in the Sun’s collection consist of ten frames of 35mm black-and-white Tri-X film, while for others an entire roll of thirty-six frames, or more, was shot. Photographers often did their own darkroom work, developing their film and making prints to show editors, in daily competition for the front page. In the ’70s alone, Vancouver Sun photographers shot almost a million frames, capturing close to one million moments in time.

So, how to choose 149 photographs to represent the decade from such a vast collection? I began with old favourites, unearthed in a quarter-century of work as a Sun news research librarian; these included images discovered over the years by Pacific Newspaper Group Library colleagues Sandra Boutilier and Carolyn Soltau, Vancouver Sun reporter John Mackie, and others.

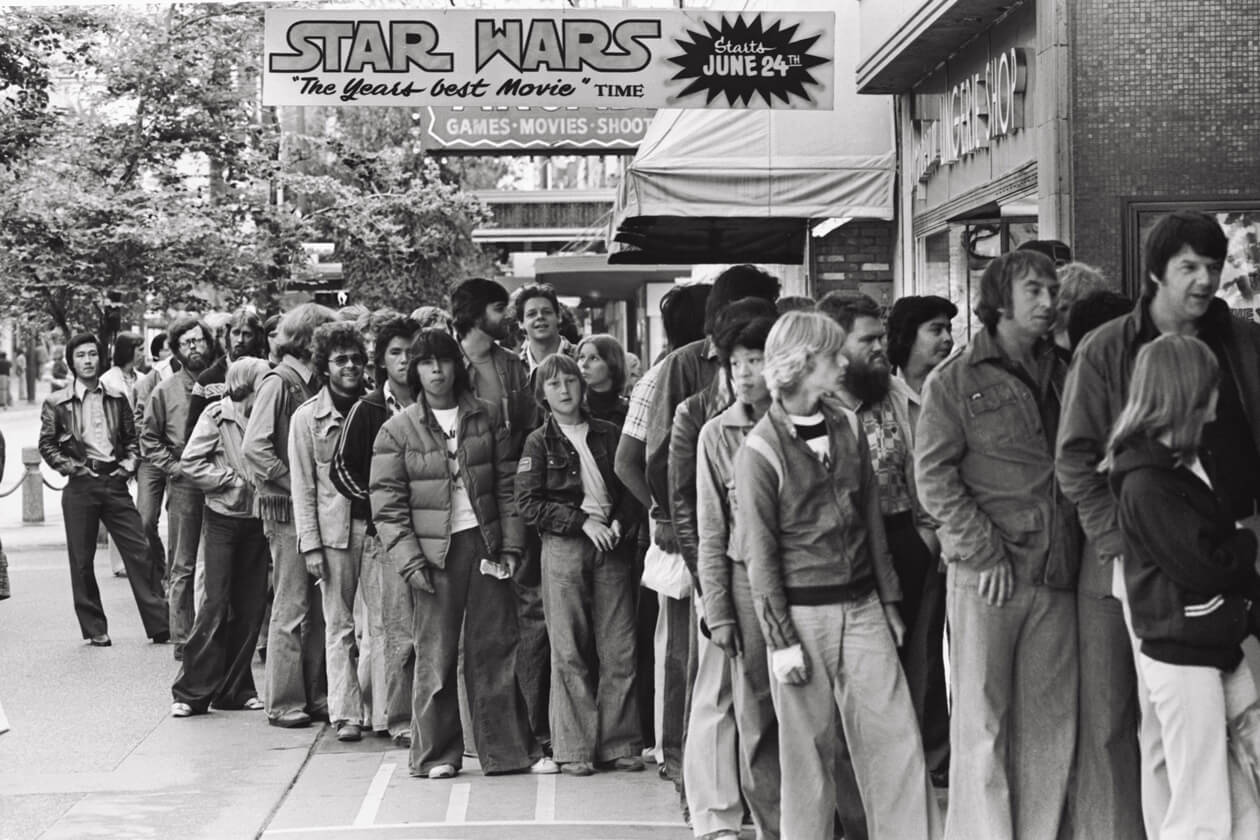

I searched through hundreds of photo files, divided into “People,” from Aadland, Beverley to Z Z Top, and “Subjects,” from Abandoned Babies to Zoos. My fingers flicked past the smaller prints of the sixties and the slick resin-coated prints of the eighties and nineties, and sought out the distinctive fibre-based prints of the seventies. I found that many of the most compelling images had been shot for everyday assignments, and that details in the background—the clothing, the automobiles, the signage—were as fascinating as the intended subject.

Negatives, located using an old index card filing system for assignments, were digitized. Often the frames originally selected forty years ago had been marked with a grease pencil. More often than not, they were still the best images. The final selection of photographs capture some of the story of Vancouver in the ’70s, and are examples of photojournalism at its best.

Award-winning photographer Glenn Baglo, who was twenty-one when he started at the paper in 1970, wrote in a 1981 article that “each photographer developed his own area of expertise, but all were required to handle a wide variety of assignments. I recall one special day I woke to a 5 a.m. phone call from the city desk directing me to a boarding-house fire. Arriving at the office after the fire I was sent to a press conference after which I shot a fashion layout. I finished the day in hospital photographing an operation utilizing a new technique for sterilization. A more average day might include photographing a construction site, covering a lecture on ‘Investing Your Money,’ shooting some knitting and taking a mug shot. Even these mundane assignments still offer a challenge.”

In an email interview, one of several conducted with staffers from the era, former Sun photographer John Denniston notes that in the seventies, “the NPPA [National Press Photographers Association] were very big into not setting things up. The old guard at the Sun found this attitude odd and felt it to be amateurish, as real photographers walked in, took over, set it up, got out and on to the next assignment.”

“The fellows would sometimes use me in their photos,” writes Susan Jackson (née Wootten), who indexed the Sun negatives in the seventies. “The most memorable setup was a shot to illustrate the money spent on a cocaine habit. The photographer rolled up a hundred-dollar bill and put a line of flour or icing sugar on a mirror. I was supposed to pretend to be snorting it. But I kept laughing and blowing the powder everywhere. Third time lucky and we got it done.”

Baglo adds, “I didn’t like doing setups, so I would spend hours on bullshit assignments, like a Christmas fair, and wait for something to happen so I could take a picture. I was taking pictures of things that were happening, just waiting for a slice of life.”

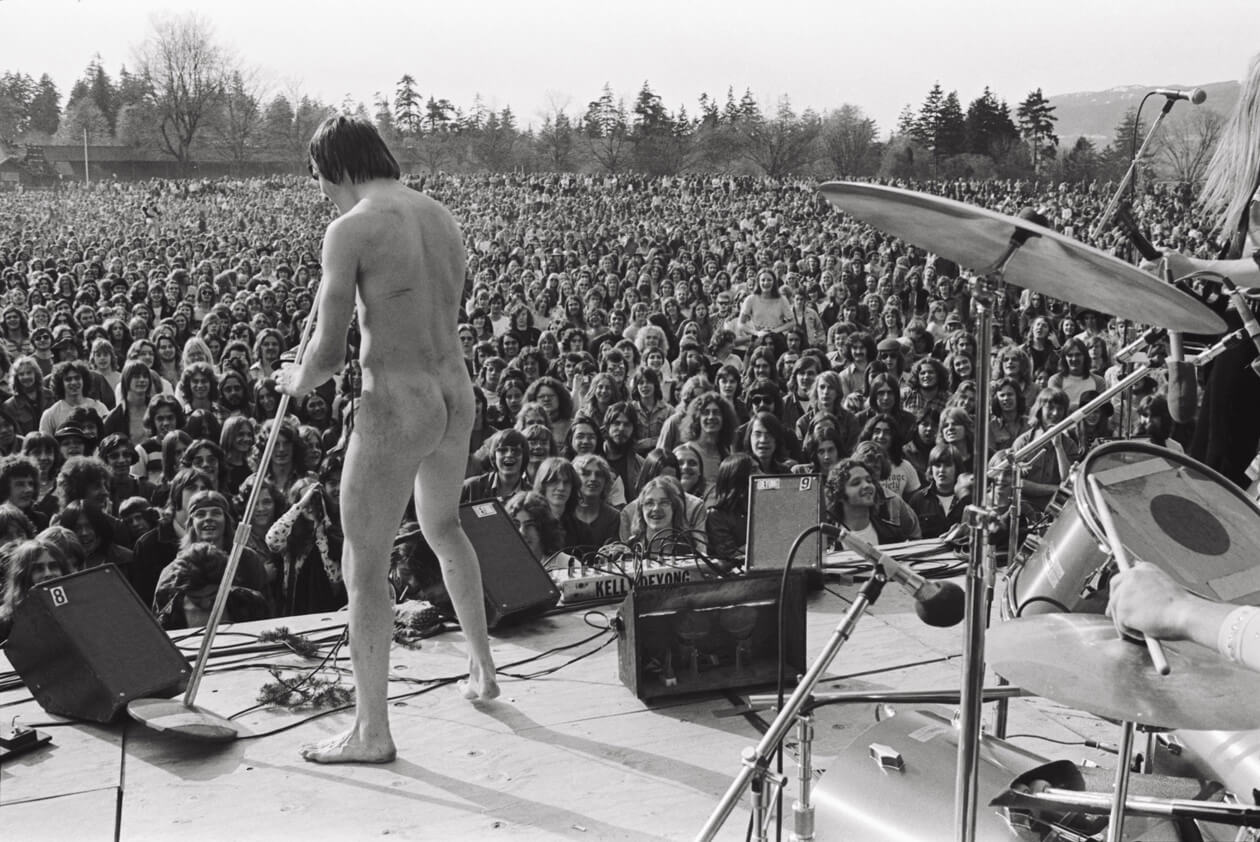

Access to people and events was less restricted in the seventies. When George Diack photographed Queen Elizabeth’s arrival at the Vancouver airport in 1971, “Photographers were required to be accredited and had to stay fifteen feet away from her. That was about it.” Baglo, who shot the photograph on page 34, remembers that “I used to go to the back door of the Coliseum and just knock and the security guys would open the door. I would say I was from the Sun and, that night [at the Rod Stewart concert], one of the guys gave me a stage pass. I shot six or seven thirty-six-exposure rolls of film because I was there for most of the concert and I was right up on the stage with him, on the side stage, so the picture I got was of him with the audience in the background.”

But it was the photo editor who chose which images were published in the newspaper. Denniston recalls that “Earl Smith was the photo editor and decided what pictures went in the paper and where. Earl had total—and I mean total—control of the pictures and how they were played. He also had first look at the page dummies in the morning and placed his pictures before any stories were slotted. This is why the Sun was a great picture paper. Pictures first, stories second.” Another seventies Sun photographer, John Mahler, notes that “in terms of feature photography and how the photographs were played, the Sun was the best. They were well ahead of the curve in big bold photo use.”

These days, citizen-shot photographs have become so invaluable to news organizations with increasingly tight budgets and resources that the livelihoods of many photojournalists are under threat. Baglo comments, “Today, everyone is a photographer. We used to go like hell to get to a fire scene or whatever. These days, everyone has a phone and they can take a picture and upload it to social media and television.”

But crowdsourced news content cannot replace the narrative storytelling and formal aesthetics of traditional photojournalism. The news photographers’ distinctively original point of view and the quality and craftsmanship of their images—like the photographs in this book—will endure the test of time.

As Henri Cartier-Bresson, the father of photojournalism, said, “It is an illusion that photos are made with the camera. They are made with the eye, heart, and head.”

Excerpted from Vancouver in the Seventies by Kate Bird, photographs from the Vancouver Sun collection, ©2016. Published by Greystone Books. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.