In July 1969, after months of feeling unwell, Jack Chambers was diagnosed with acute myeloblastic leukemia, a terminal illness that kills its victims in approximately three months if untreated. Unsure of how much time he had left, the painter from London, Ontario, turned his attention to the practical matter of providing for his family. He informed his dealer Nancy Poole that unlike other artist representatives she would no longer determine the price of his work based on current market values. He, Jack Chambers, would now decide what his paintings were worth, and, says Poole, “it was my job to find a buyer.”

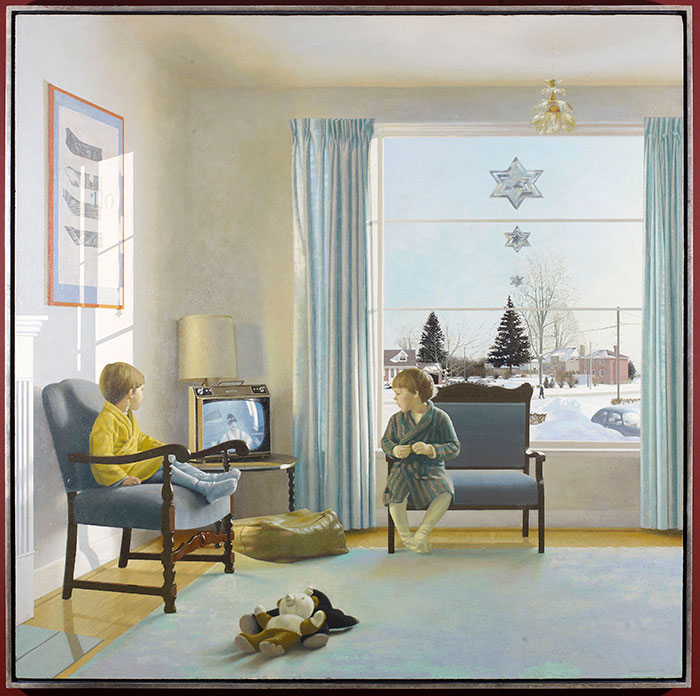

Still, she was stunned the following spring when Chambers demanded $25,000 for Sunday Morning No. 2, a picture of his pyjama-clad three- and four-year-old sons watching television in the family living room. “To put that amount in perspective,” says Poole, “it was five times” what had been paid for his last major painting, 401 Towards London No. 1, just a year earlier. She was skeptical about making the sale, but in June 1970 Eric A. Schwendau, a local financial consultant, bought the piece for its asking price, and overnight Jack Chambers became “Canada’s highest-earning artist.” He told the press, “Now I think I’m getting about what my work is worth. But until recently, I thought I was underrated and underpaid.”

The sale of Sunday Morning No. 2 caused controversy. Greg Curnoe, the well-known London painter, was so angry he stopped speaking to Poole, believing she had undermined the Canadian art market. “Of course, he stayed friends with Jack,” says Poole. “Jack said, ‘I’m a dying man. He can’t get mad at me.’ ” But for Chambers, the discord couldn’t have come at a better time. In September 1970, the Vancouver Art Gallery opened a retrospective exhibition of his paintings, which, coming just months after the fracas surrounding the sale of Sunday Morning No. 2, put him front and centre in the Canadian art world.

Reviews of the exhibit unanimously asserted that at age thirty-nine the country’s best-paid artist had hit his stride. Chambers had painted Sunday Morning No. 2 in a style he called perceptual realism, which he adopted in 1968, reinvigorating his reputation as an artist. Before perceptual realism, wrote Geoffrey James in Time, Chambers was “not smiled upon by the Canadian art establishment.” Many of the cognoscenti had dismissed him as a copyist, but as Alan Walker observed in Canadian magazine, he was praised now for “his poetic sensibility and his subtle colouring.” Along with Michael Snow, Joyce Wieland, Greg Curnoe, and Tony Urquhart, Jack Chambers had arrived as one of the most notable artists of his generation.

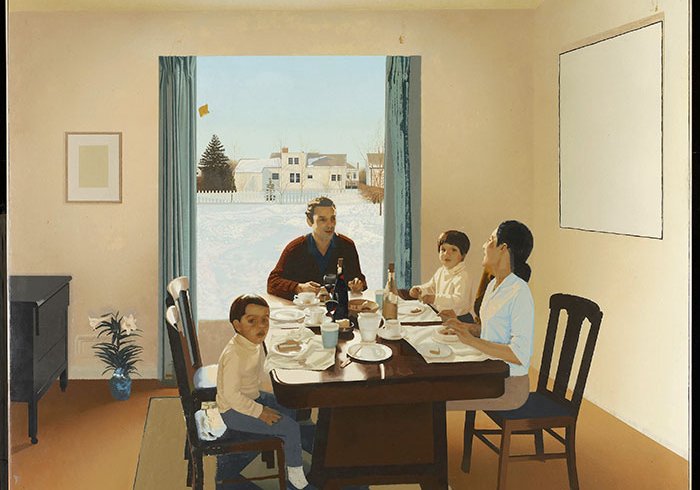

More than a hundred paintings were exhibited at the 1970 retrospective, but the buzz surrounded one that remained curiously unfinished. Called Sunday Noon (and later renamed Lunch), it was a portrait of the artist sitting down to a winter’s midday meal with his wife and two young sons. It was included in the show because, as Chambers wrote in a piece for Artscanada magazine (where he previewed the work-in-progress), it embodied perceptual realism. Viewers noticed that although the faces of the Chambers family were just taking form, a phenomenal composition was emerging from the canvas. When the retrospective moved from the VAG to the Art Gallery of Ontario, the reviews were equally enthusiastic. Not only was Chambers breaking art market records, they gushed, but judging from the exhibition’s unfinished work, Lunch, he was about to do it again.

Only he didn’t. Although he defied the odds and lived for another nine years, adopting a macrobiotic diet, travelling to India for spiritual treatments, and—despite periods of extreme fatigue—creating more than thirty major works, he never completed Lunch. It was the one significant piece left unfinished when he died. And now, forty-one years after it was first exhibited, it’s in the spotlight once again as the AGO opens a new retrospective called Jack Chambers: Light, Spirit, Time, Place, and Life. As the exhibition’s curator, University of Toronto professor Dennis Reid, explains, “All of the show’s themes are in that painting.” But while it was once regarded as a work of hope and possibility, it’s now a mystery. Why didn’t Chambers finish his masterpiece?

Born in London at Victoria Hospital, on March 25, 1931, Jack Chambers grew up in a modest Baptist home, the son of a welder. Throughout his childhood and teenage years, he took little interest in school, which he described as time spent “waiting between recesses and the summer holidays.” But that is where his art education began, well and early. At Sir Adam Beck Collegiate Institute, he was taught by the author, illustrator, artist, and art therapist Selwyn Dewdney (he and his wife, Irene, became the boy’s second parents after his mother died). At H. B. Beal Technical School, he studied with the London sculptor, painter, and muralist Herb Ariss, who advocated figurative drawing as the cornerstone of art. And by the time he reached eighteen, he had won the Young Artist prize at the Western Ontario Annual Exhibit, for his still life Lillies.

In 1953, he quit the University of Western Ontario after only a year, but not before establishing what would become a lifelong friendship with Ross Woodman, a scholar of the poet Shelley and an art collector. Searching for a way to become a serious painter, Chambers decided to leave Canada for Europe. He wandered around Italy, Austria, and the south of France, where—famously—he demonstrated his extreme self-confidence by scaling the walls of Pablo Picasso’s home to meet the master and seek his artistic advice. Remarkably, Picasso gave him an audience and recommended that he study in Spain. And so that’s what he did, spending the next five years in Madrid, immersed in classical arts at the Escuela Central de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

The young Canadian fully embraced Spain. He learned the language, fell in love with a sophisticated Argentine beauty, Olga Sanchez Bustos, and converted to Roman Catholicism. For Chambers, the moral rules of the Catholic Church provided a tangible spiritualism he could work at, as he explained, “the same way that the academy provided standards to direct my anxieties into specific problems to be solved.” Spain also introduced him to the baroque masters Juan Sánchez Cotán and Francisco de Zurbarán, whose works became a continuing inspiration and influenced his development of perceptual realism.

Lunch looks a lot like photorealism, a style of painting popularized in the late 1960s by a group of American artists, including Chuck Close and Richard Estes. But according to Chambers, perceptual realism had nothing to do with what was happening south of the border. The painting’s genealogy (like that of 401 Towards London No. 1 and Sunday Morning No. 2 before it) stretches back to seventeenth-century Spain and a spiritually charged style that 300 years later would stop Chambers in his tracks.

Like the Italian baroque artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Cotán and de Zurbarán rendered religious scenes with such shocking, lifelike accuracy that fruit appeared edible and saints seemed to breathe. But whereas Caravaggio flaunted his artistic virtuosity by packing his works with theatrical sensuality and tension, Cotán and de Zurbarán eschewed such overtly stylistic flourishes. Pious and unassertive, they endeavoured to present God’s world as realistically as possible. To do otherwise would be a hubristic declaration that the earthly realm could outdo what heaven had perfected. As the art historian Norman Bryson writes, for de Zurbarán, even the presence of visible brushwork “would be like blasphemy.”

Chambers fully intended to build a life with Olga in Spain. By 1960, he had purchased a flat in Madrid, where he held his first solo exhibition a year later. His plan changed dramatically in March 1961 when he learned that his mother was dying of cancer. He returned to Canada for a visit, but when he discovered London’s burgeoning art scene—including Greg Curnoe, Tony Urquhart, and Murray Favro—he decided to stay. Olga joined him in 1963, the year the couple married at St. Peter’s Basilica in London.

From the time he converted to Catholicism in 1957, Chambers said he sought ways to pursue “the laws of Moses,” through “the love of art.” But it took nine years before he figured out how to paint God. On a bright October morning in 1968, he checked his rear-view mirror while travelling east on the 401 toward Toronto. He caught a glimpse of the landscape behind him: a majestic vista of russet trees and lush green hillside beneath an endlessly wide-open sky. It was a moment, he later wrote, of heightened amazement, “where reality is so imminent that one feels he has stepped off the conveyor belt of time” to glimpse the world in pause. It was a vision both potent and precious that made him state one word aloud: “Wow.”

The experience led Chambers to perceptual realism, which was as much a philosophy, rooted in Catholic doctrine and the writing of the French phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, as it was a style of painting; and it marked a radical departure from his previous work, which cut a wide swath across a variety of genres. In the late 1950s, his style was influenced by abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. By the 1960s, his focus had shifted and he was creating surrealist-inspired dreamscapes. Starting in 1965, he devoted himself exclusively to making so-called “silver paintings,” works that conveyed movement with aluminum pigment. And then, in 1966, he quit painting altogether to focus on making films.

After a two-year hiatus, he picked up his brush anew. As a perceptual realist, he began each of his pieces with a grid of perfectly spaced horizontal and vertical lines drawn over a photo, usually one he took himself. Then, working square by square, he transferred every detail of his source image onto a large plywood or canvas surface on which he had placed corresponding lines. Calling the paintings he made prior to 1968 ego driven, he began to focus on subjects of everyday life (driveways, houseplants, children’s toys), which he elevated from the ordinary to the extraordinary. This new approach enabled him to shake off his Caravaggesque approach, gave him the tools to become as penitent as Cotán, and made him famous.

It also presented huge technical challenges. A scene had to be rendered with lifelike precision, which may explain in part why he never finished Lunch. Beneath the table where Chambers sits with his family, a richly patterned oriental rug stretches across the dining-room floor. Even art’s greatest virtuosi—da Vinci, Michelangelo, Vermeer—would have been humbled had they set out to render its woven texture; its swirling brown, navy, and white arabesques; its endless geometric ornaments. “The painting should have taken him no more than twelve months to complete,” says Kim Ondaatje, who met Chambers in 1967 when her then-husband, author Michael Ondaatje, took a job in the University of Western Ontario’s English department. An established artist herself, she frequently visited Chambers in his studio, where he spent weeks at a time filling in the rug beneath his family’s feet, only to wipe it out and start over again—a cycle that went on for years.

“Jack, the rug isn’t important,” she would tell him. “You’ve already got the painting; it’s the feeling of the family.” But it was no use. Just as there can be no Mass without a cross by the altar, for Chambers there could be no perceptual realism without a meticulously faithful rendition of his vision.

But the technical demands were not the only obstacles stopping Chambers from finishing Lunch. “Jack was extremely motivated by money,” says Nancy Poole. It was the reason he switched from Av Isaacs, then the reigning Toronto art dealer, to the London-based Poole in 1970. “I was considerably less experienced than Av,” she says. “But the commission I took as a dealer, 10 percent, was also considerably lower.”

The arrival of his sons, John and Diego (born in 1964 and 1965), convinced Chambers that artists were entitled to make a decent living. Like other fathers of his day, he was ambitious and focused on his career, leaving his sons to be raised by their mother. But he took his role as a provider and family man seriously. Every morning, he set out for his studio, where he worked for eight or nine hours at a stretch, to earn enough to make ends meet. For him, money and family stability were paramount and inextricably linked. It was money that drove him, along with Tony Urquhart and Kim Ondaatje, to found Canadian Artists’ Representation in 1967. At the time, galleries didn’t pay artists copyright, usage, and reproduction fees, an oversight CAR quickly remedied.

After the sale of Sunday Morning No. 2, Chambers’ pictures sold quickly and for increasingly higher prices. In 1971, when his epic work Victoria Hospital (where he went for treatment) fetched $35,000, he felt reasonably certain that Lunch would sell for more than any of his previous works had. What he hadn’t anticipated, however, was Olga’s request that he give the painting to her. This, according to Poole, explains in part why Chambers never completed his family portrait. “If he finished the painting,” she says, “it would have been sold. Absolutely.”

Chambers’ friend Ross Woodman has another theory: the fact that Lunch was originally called Sunday Noon explains why Chambers couldn’t finish it. The title Sunday Noon connects it to five paintings he created between 1963 and 1977, all of which have the words “Sunday Morning” in their titles. What they also have in common is that they place members of his family in situations that often reference Christian symbolism and art.

In Sunday Morning No. 1 (1963), Chambers sets his kin—relatives young and old, from generations recent and past—among depictions of Christ, Moses, and Elijah. The Biblical figures are exact replicas of characters presented in Transfiguration, the classic High Renaissance altarpiece by Raphael. In Sunday Morning No. 2 (1968–70), a stuffed doll lies on the living-room floor like a crucifix, forming the apex of an inverted triangle that connects John and Diego Chambers. In Sunday Morning No. 5, Diego reads a book near a scene of Christ’s Nativity, as if in prayer. In Sunday Morning No. 3 (1975) and Sunday Morning No. 4 (1975–76)—two works that contain the same interior image of a window in the Chambers home—a postcard-sized image of a radiant, resurrected airborne Christ is taped to the glass. The picture is a detail of the Isenheim Altarpiece executed by Matthias Grünewald from 1506 to 1515. On the window ledge of Sunday Morning No. 3 and Sunday Morning No. 4, Chambers includes a photograph of his son John on his back with his legs in the air; the child’s stance is identical to the poses of Roman custodians who in Grünewald’s masterpiece fall head over heels at the sight of the Resurrection.

In all of the Sunday Morning works, the artist’s message remains clear: the Holy Spirit dwells among his family. In Woodman’s view, Chambers intended to make Lunch part of a body of work “replete with spiritual meaning.” Its iconography links it to religious paintings dating back to the sixth century, when artists first depicted people at a table eating a meal as a representation of Christ’s Last Supper. Following in the footsteps of Hans Holbein the Younger, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, and Salvador Dali, Chambers positions his family in front of a wide, bright window with empty plates, fresh linen, and wineglasses on the table before them. The lily in the bottom left of the picture reinforces its message: the flower’s beauty springs forth from a gnarled and lifeless mass that symbolizes Christ’s Resurrection.

Woodman often visited Chambers as he worked on Lunch, and says that when the artist began the painting “he received communion almost daily and talked endlessly about its miracle.” Although an initial reading might suggest that Chambers intended to depict himself as Christ, Lunch is a portrait of the artist and his family as recipients of the Holy Sacrament, which will be offered, not by Chambers, but by the figure who will take a seat in the empty chair to the artist’s right. As in all of the other Sunday Morning paintings, Christ is also present in Lunch: he is the Holy Spirit entering the room, the light reflected in John’s and Diego’s eyes.

Why was Lunch left unfinished? Woodman believes it comes down to chronology. Chambers began the painting before he was diagnosed with acute leukemia. Once he was sick, he felt it would take on a life of its own. “Have you ever seen someone who has acute leukemia? ” asks Woodman. “Chambers looked like hell. No matter what interpretation he had devised for Lunch, his illness would cause it to be read differently. It was something he would not allow to happen. He didn’t want to get caught up in the mythology of Christ. He refused to paint himself with a crown of thorns.”

Chambers died on April 13, 1978, at Victoria Hospital. At his bedside sat Olga, holding his right hand, and Nancy Poole holding his left. Irene Dewdney, his surrogate mother, was there, too, standing with her back to the wall, the apex of a tight triangle of love. Until his final moments, the artist remained conscious, keen to stay a part of the world he had rendered in Lunch, which would have been a difficult work even if he hadn’t fallen ill. Art history has a long tradition of self-portraiture, but startlingly few examples of painters who dared to depict themselves in the company of their wives and children. For all the portraits Picasso painted of himself, his wives, and his children, he never set out to create a painting of family togetherness like Lunch.

No one will ever know why Chambers failed to complete his most promising work, but perhaps the answer lies in the question: why did he start it? Here the facts are clear. At the top of his game as a painter, at a time when he was young enough to enjoy his family and yet old enough to appreciate the fragility of life, he had the confidence to tackle one of art’s most iconic religious themes in one of its most unrealized genres of portraiture. With his technical, commercial, and spiritual goals aligned, he was ready to paint a psychological and spiritual image of family intimacy. After his life took its tragic turn, the challenges of perceptual realism, his preoccupation with money, and a fear that Lunch would be misunderstood proved to be too much. Jack Chambers had no choice but to leave his masterpiece unfinished.

This appeared in the January/February 2012 issue.