The first time I performed at the Basement Revue in Toronto, a live series bringing together some of the country’s best musical and literary talents on the same stage, in 2014, I was pretty sure Damian Rogers had mistaken me for someone else. But then it became clear that Damian, co-host and literary curator of the series, was making a concerted effort to book women and writers of colour. As I worked through my performance anxiety backstage, aware I was in the presence of various Broken Social Scene members, I wondered what would become of all of this.

Tara Williamson, a Cree/Anishinaabe singer, and I were the only Indigenous artists on the bill that evening, and the audience, attentive as they were, were also like a blanket of snow. The only non-white people I saw in the audience were guests I had brought with me. I remember thinking a lot of what ifs that night. What if the lineup had been rich with Black and Indigenous artistic talent? What if our audience was dancing too? What if this mix of storytelling and music, and the politics inherently woven into our work—a mix that has sustained communities of resistance for centuries—was performed in Indigenous communities? What kind of new worlds could be collectively built if we did things differently?

Three years later, I found my answers in New Constellations, a nation(s)wide tour featuring musicians and artists, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. The tour was curated and produced by Damian and her Basement Revue co-host, Jason Collett, along with my dear friend Jarrett Martineau of Revolutions Per Minute, a global, Indigenous music platform and record label. The project included a thirteen-stop tour, a mentorship program, a community-based arts-and-music workshop series for Indigenous youth, a digital curriculum, and a documentary film of the tour. There is no doubt in my mind that the logistics of moving fifty diverse artists across Indigenous territories in November was its own nightmare, and I have deep respect for the curatorial and production team. They likely only needed a little bit of therapy upon their return home.

My band (me; my sister, singer-songwriter Ansley Simpson; Cree cellist Cris Derksen; and Nick Ferrio, a seasoned musician and the pride of Peterborough, Ontario) was among the core acts, and we performed at each stop on the tour. We lived together on the tour bus for two weeks, playing shows from Edmonton to Halifax. What follows are my notes—the things that moved me, the stories that I’ll carry with me, and what I’ll try to remember above all else.

ᒥᓵᐢᑲᐧᑑᒥᓂᕁ : misâskwatôminihk: Saskatoon

There were seven stops on the western leg of the tour across Anishinaabeg, Métis, Assinibione, Nehiyawak, Stoney Nakota, Dakota, Siksika, Piikuni, Kainai, Tsuut’ina, and Odawa lands. Seven. It’s an important number in a lot of our cultures. Our ancestors knew that something important happens when you re-enact something with intention through time and across space. Repetition turns into ritual. Mechanics soften into nuance. You hear things you missed the other times. You see things you didn’t know were there.

This was our first show. It wasn’t as stressful as the previous night, when the tour musicians had watched my band perform a solo set at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. I’d also forgotten my mic in Winnipeg. But at least for this first stop, we’d have to do only three songs.

What worries me more is how to handle being social for the eighteen hours a day that we will be working in tight spaces and under stressful conditions, mostly trapped on a moving bus. It becomes clear in Saskatoon that this is what we’re all worried about.

But I’m surrounded by so many role models. I want to be poet Louise Bernice Halfe when I grow up. She is magnificent, and so many of us would not exist without her work. And she doesn’t get her stage clothes at Joe Fresh.

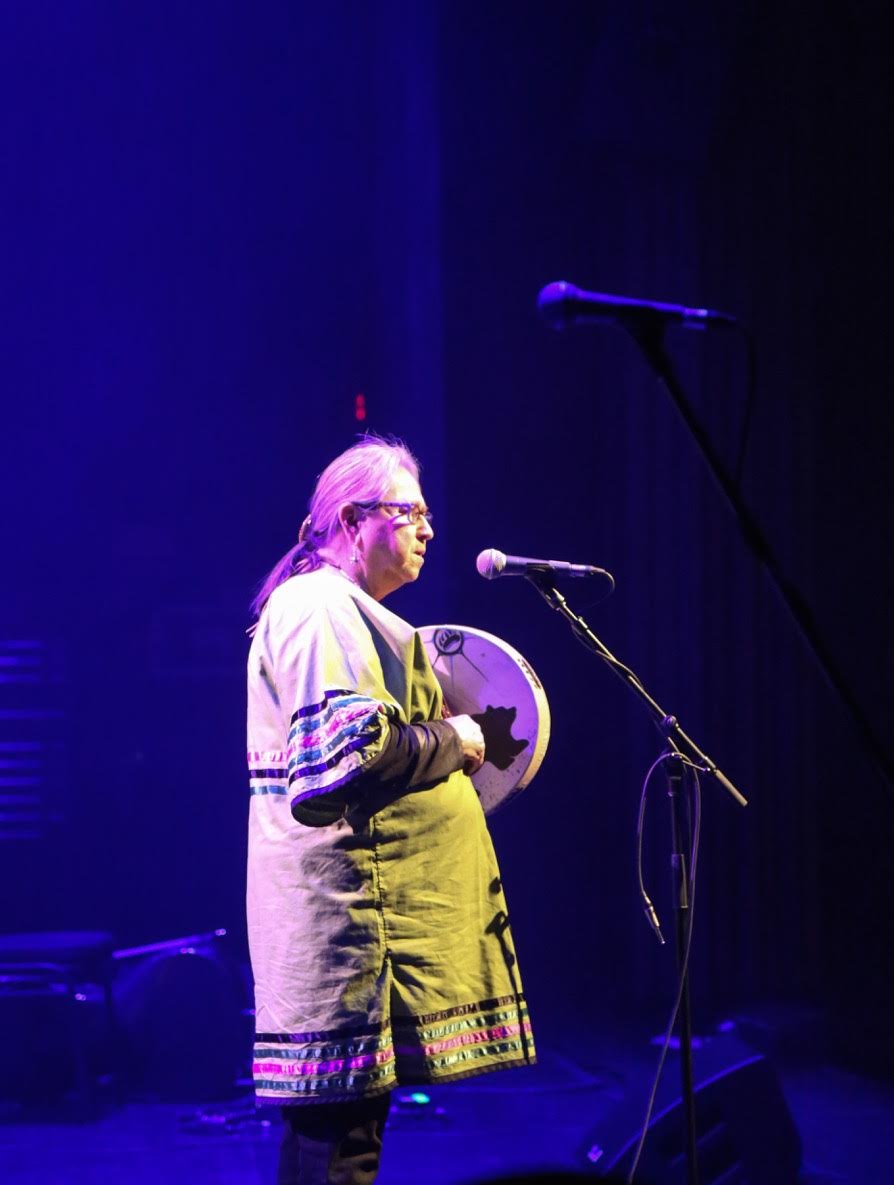

I want to be singer Elisapie Isaac when I grow up. If there were a human, Inuk version of the Headspace meditation app, it would be Elisapie. She is an ocean of calm and an abundance of kindness. For her final song, Elisapie did a Willie Thrasher cover, called “Wolves Don’t Play by the Rules.” She began by introducing Willie—an Inuk from Aklavik, Nunavut, who is a residential-school survivor. Her performance was the most profound thing I’ve ever witnessed, and by the time we reached Prince Albert, she would invite us all on stage to sing with her. I was singing too.

Sometimes when you’re on stage, you can’t help but fall in love with the audience, particularly when you see your people there. Kids, Elders, high-school students all smiling back at you.

Moh-kíns-tsis-aká-piyoyis: Wincheesh-pah: Otos-kwunee: Kootsisáw: Klincho-tinay-indihay: Calgary

I wake up to a very cool meme from my kid of our tour bus as the Knight Bus from Harry Potter. I like the idea that this bus has appeared out of nowhere and every single person on it needs to be here.

We are parked on a side street at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology in Calgary. By the time we load into the Gateway, a student bar, I’m getting worried. It’s the end of term. The stress on campus is palpable, and no one really goes to poetry recitations to blow off steam. Poet Joshua Whitehead is performing tonight, and I want the audience to give him the absolute respect he deserves, even though they may be here just to see July Talk, who are also performing tonight. Or maybe they’re just trying to forget a disastrous exam.

I watch the melatonin-challenged faces of the audience. I needn’t have worried. With each act, their expressions of apprehension morph to wonder and then to joy. Joshua Whitehead blows minds and hearts that night, commanding the space and making us so very proud. Mob Bounce pulls the rowdy energy out of the crowd and transforms it into pure Indigenous joy. By the end of their set, we’re all dancing.

This is medicine in an unlikely place. Our ancestors would be so proud.

ᐊᒥᐢᑲᐧᒋᐋᐧᐢᑲᐦᐃᑲᐣ : Amiskwaciwâskahikan: Edmonton

We wake up in Edmonton, outside of the Starlite Room. Another bar show, this time with a metal band in the basement. Many of us tweak our sets for a standing audience. Some of us can’t. Backstage in this tiny cement green room, beside wine bottles and crackers, we call on extra help. Sage is burned. Old songs are sung.

I want to be Marilyn Dumont when I grow up. Every word of her poetry is pure Cree/Métis brilliance and fire. I know things are going to be fine when I look out into the empty venue while sound checking “Come Get Your Love” and Marilyn and her crew are at the back just dancing up a storm. We should all read Marilyn Dumont and dance together more.

The highlight for me is Billy-Ray Belcourt, from Driftpile Cree Nation, performing a laugh-out-loud-until-your-abs-are-burning monologue about anal sex. I still have not recovered.

Kiskaciwan: Prince Albert

We have a high concentration of Shania Twain fans on tour, which becomes clear when we realize we’re playing Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, during the Grey Cup, and she’s performing during the half-time show. We huddle around the TV in the green room to watch a sparkly Shania dogsled onto the stage—which inspires a few face palms plus, during the show, a cover of “You’re Still the One” by folk artist Safia Nolin, with July Talk’s Leah Fay and composer Jeremy Dutcher singing backup.

Kiskaciwan gives Jeremy a standing ovation at the end of his set that night. And not just because he climbed up onto the grand piano and sang into the strings.

After the show, we visit with some of the audience at the merch table—young people who’ve come to see July Talk and are leaving with selfies with Peter Dreimanis and Leah Fay, but also with overwhelming pride and inspiration from the Indigenous musicians they’d never dreamed existed. This alone makes everything worth it.

Wiin Nibi Aang: Métis Homeland: Winnipeg

Winnipeg has been good to me. I met my partner of twenty years while sandbagging during the 1997 flood of the century. I graduated from the University of Manitoba with my PhD. I published my first book with ARP Books. The city makes me think of garbage mitts. Hunky Bill’s Perogie Maker.

Red Rising Magazine partners with us to provide workshops on writing, songwriting, and DJing during the day while the rest of the crew sets up at the West End Cultural Centre. John K. Samson comes to my sound check and claps. I fully admit I do not know a lot about poetry, but what I do know, I’ve learned from studying John’s work. By studying I mean belting out his songs in my kitchen for the past two decades and then writing the lyrics out and trying to figure out what he is doing structurally. Jason Collett asks me to introduce John backstage. I said some version of, “As an emerging Indigenous artist, I needed two things—someone to believe in me and a platform. John gave me both.”

Aniimiki Wajiew: Thunder Bay

Thunder Bay is one of my favourite places in the world. The Anishinabek on the north shore of Kitchi Gaming (Lake Superior) are powerful people, and they reflect the land of which they are a part: Nanabozhoo (Sleeping Giant) resting in Kitchi Gaming, Aniimiki Wajiw towering out of nowhere (Mount McKay) and the Gaa-ministigweyaa (Kaministiquia River) with two large islands and its mouth.

We begin the morning playing basketball at Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School, which hosts students from twenty northern First Nations—a school established by parents and Elders in the Sioux Lookout District. A school full of Anishinaabeg love and brilliance. We do eight workshops that day and fall in love with these students and this school.

The Polish Hall is one of my favourite venues precisely because it is a Polish hall. The community is filled with the energy of weddings and Christmas concerts. Jason tells me this venue requires pure faith: you have to phone to book it and hope someone’s there to pick up. There is no website, no answering machine, no email. But there are homemade perogies, cabbage rolls, and tablecloths.

This is also the land of Waawaate Fobister, a playwright from Grassy Narrows First Nation, and Waawaate does not disappoint. He reads poetry without speaking a word, instead evoking it with a kinetic, real-time insertion of a beautiful brown storied body in a dance performance that reminds me of both Kitchi Gaming and Nanabozhoo.

Jana-Rae Yerxa is another outstanding part of this night. The whole day, I think about Barbara Kentner, a young Anishinaabekwe mama who died earlier in the year after she was struck by a trailor hitch thrown from a passing car. I lived in Thunder Bay two decades ago, and I was familiar with “spooning”—white people throwing various objects at Natives from moving cars. I wanted to somehow honour Barbara and her family. Jana-Rae, with her fiercely loving poetry, does that better than I could have imagined.

Wikwemikong, Odawa Minis: Wikwemikong

Sometimes you have to borrow clean underwear from your bandmate. That’s just how it is, apparently.

Performing in Wikwemikong is something that I will never forget. This is the first time I’ve performed in front of a Nishnaabeg audience in not just any Nishnaabeg community but the epicentre of Nishnaabeg theatre, language, and visual arts. Nearly all my language teachers—Edna Manitowabi, Shirley Williams, Liz Ozasamik, and Vera Bell—are from here, and the list of artists that this community has gifted us is long and spans decades.

Jeremy plays early on in the set. He introduces “Honour Song” and my people stand up, as we do when we sing honour songs. This moment. This is the most proud of being Nishnaabekwe I’ve ever felt. The knowing. The seamless respect.

I learn a little more about solidarity from bandmates Leah and Peter, both of July Talk. They don’t take up much space, despite being the most famous and successful musicians on the tour. They are gentle and kind. They listen. In the dressing room on the final day of the western leg, I find out they’ve been reading my book Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back as we travelled together across the prairies on the Knight Bus.

K’jipuktuk: Africadia: Halifax

K’jiputuk is the first stop on the eastern leg of the tour. On this leg of the tour we will travel through Mi’kmagi, Wolastokuk, Kanien’kehá:ka homeland, and Omàmìwininiwag (Algonquin) lands. Our core roster of musicians is smaller, fitting onto one bus this time, and local writers and musicians join us on stage at each stop.

George Elliott Clarke forgets to bring his book, which all writers have done more than once. But most writers are not George Elliott Clarke. He doesn’t need his book. He just needs the mic, because the stories of his people flow out of him fully formed, with heartbeats and Black joy. George always, always shows up with incredible energy. Elder artist George Elliott Clarke always brings it. And so does Shalan Joudry, an emerging writer from Bear River First Nation, who brings the land and the water right into the theatre with her.

This is Lido Pimentia’s first visit back to Halifax since she, out of sheer love, invited people of colour to the front during her act at the Halifax Pop Explosion in October, then stood up to a white volunteer who refused to make space. Social media predictably responded with a litany of white supremacy aimed at Lido. When I meet her, I hug her and tell her I have her back, and I mean it.

Fredericton, Wolastokuk

Wolastoqiyik means “people of the beautiful river,” and in my travels, I’ve learned there is always something special about beautiful river people. The beautiful river people we meet in Fredericton are Jeremy’s kin. His Elder Maggie Paul opens the show by speaking in Wolastoqey. I’m standing beside Jeremy backstage. He laughs, he cries, he does high kicks. It is beautiful to witness, especially when she says, “Jeremy is the one we have been waiting for.” Seeing Jeremy in his home, surrounded by aunties and family, wearing his fancy coat for his mom, on the high-school stage where he had last performed “Bohemian Rhapsody,” I start to understand where this magnificent talent comes from. But it isn’t until I sit beside the Wolastoq River that I begin to understand that his music is the river. When I listen to his Elder, I realize the empty seats are for our ancestors.

Rich Aucoin steals my heart a little that night. I’ve played with Rich at Luminato before, and it was maybe the most fun I’d ever had. I remember a parachute, all the confetti in Toronto, and a lot of dancing like no one is watching, and I wondered how he would translate that into a sit-down theatre. Well, he did. He made a beautiful video that affirmed and recognized several of the core artists on the tour and the work that we do.

Tiohtiá:ke, Montreal

We wake up in Rotinoshonni territory. My unpaid stylist endures a twenty-minute shopping trip with me, to find appropriate clothing for a Now magazine shoot. I text and roll my eyes while he scurries around finding everything I apparently need. I expunge four decades of internalized slut shaming while he patiently tells me I look great in sparkles. He finally convinces me to try on heels. I decide I look Louise Bernice Halfe-y.

Odawa: Ottawa

The bill is stacked and the time is tight. There’s a Tribe Called Red collaboration with Lido, Jeremy, Leonard Sumner, and Shad—an otherworldly ten minutes of pure Indigenous and Black genius. The world needs more Shad.

After the show, we end up in Chinatown for pho. Nick Ferrio is epic at a lot of things, two of which are stories and jingle writing. Over 2 a.m. noodles, Nick recounts the story of how, at fifteen, working as a park ranger at Sibbald Point Provincial Park, he became incensed that the reservations phone line had no jingle. Young Nick wrote a jingle, recorded it in his bedroom on a four track, booked a meeting with Ranger Rick, and holy crap, Ontario Parks, you missed the boat.

Kitigan Ziibi

Community shows will always be my favourite. Writer and law professor Tracey Lindberg drives through the snow to be with us, and she speaks to the audience through the mic, on the advice of an Elder, “as if this was the only time she would ever have the opportunity to speak with us”. Hearing her read from her novel, Birdie, and hearing the audience laugh when she introduces “Jesse from The Beachcombers” is a moment I’ll put in a jar and save forever.

And my heart, Lido. She invites four young Anishinaabekwewag on stage with her to start her set with a round dance song. Sharing space. Holding each other up. Reciprocity. I am so grateful for Lido’s natural ability to be in community with us. This is her first time on a reserve, and her kindness, openness, and humility will not soon be forgotten.

It’s hard to know how to process what happened on this tour or even the idea that bringing Indigenous and non-Indigenous musicians together on a tour is somehow a novel idea in 2017. We have been living with each for four centuries.

This tour felt different. It felt like an Indigenous space. I felt supported and taken care of. I felt artistically nurtured. I felt surround by insane, diverse, creative energy and creative excellence. It felt like family. It felt like ceremony. It felt like with a lot of hard, hard work, things might be okay.