This is the story of how love and hate got swapped on Valentine’s Day, twenty-six years ago this week.

On February 14, 1989, an angry, calculating Ayatollah Khomeini broke with Islamic tradition and changed the world by issuing a fatwa that put a bounty on a British, Booker Prize–winning novelist. Specifically, the ayatollah broadcast a message on Tehran Radio declaring: “I inform the proud Muslim people of the world that [Salman Rushdie] the author of the Satanic Verses book, which is against Islam, the Prophet, and the Koran, and all those involved in its publication who are aware of its content, are sentenced to death.”

Prior to this moment, issuing a lethal fatwa against a citizen of a foreign, non-Muslim country would have been unthinkable for even the most senior Shiite cleric. That all changed with Ayatollah Khomeini’s broadcast, which was deliberately crafted to overshadow the end of the Cold War and the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan that February 15. The ayatollah knew exactly what he was doing in positioning himself on the world stage as the global spokesperson for Islam in this shocking way, and he used Rushdie to get there.

On Valentine’s Day 2015, which comes more than a month after French-born assassins committed mass murder in the Parisian offices of a cartooning magazine, such barbarism has become part of the geopolitical landscape. It is taken for granted that jihadists seek to kill all manner of writers, artists, and journalists who run afoul of their twisted versions of Islam. But that first fatwa caught Rushdie, and the intellectual world more generally, completely off guard. It was a new kind of threat.

The irony is that France, the most recent site of this spectacular, internationally dispatched form of Khomeini-style terrorism, granted the ayatollah asylum (after Saddam Hussein eventually expelled him from Iraq, where he spent the years between 1965 to 1978 in exile). It was from his French house in Neauphle-le-Château that the ayatollah plotted the overthrow of the Shah of Iran and no doubt, in the back of his mind, war on Iraq.

After he returned to Iran on February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini and his Islamist regime overturned the Shah’s secular pro-Western Iranian government and replaced it with a Shiite theocracy. Ignoring divisions between mosque and state, he declared Islamic jurists to be the country’s supreme authority.

He also claimed to have transcendent religious authority. Driving his fanatical hatred of the West—and the United States more specifically—was the view that the Islamist takeover in Iran signalled a series of events that would usher in the fabled Twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, mankind’s ultimate saviour. As Vali Nasr has written in The Shia Revival, slaughtering “enemies of the Twelfth Imam” (whom Ayatollah Khomeini claimed to represent) within Iran was part of this revolution.

Likewise, slaughtering foreign infidels such as Salman Rushdie was part of this larger eschatological agenda—notwithstanding the fact that the ayatollah reportedly never actually read The Satanic Verses.

In short, Ayatollah Khomeini was Islamism’s Lenin, and 1979 was Shia Islam’s 1917. The Rushdie fatwa was to be his decisive symbolic arrow shot into the heart of the corrupt liberal West, and was his personal departing blow before his own death in June 1989. As noted French scholar Gilles Kepel wrote in Jihad: The Trial of Political Islam, “At one stroke, dar el-Islam [the house of Islam] was made universal, and its politics was expanded to include Muslim immigrants to the West, who became first the hostages then the actors in a worldwide struggle for control over Islam.”

Among Ayatollah Khomeini’s supporters were some of the cream of Western intelligentsia—writers who imagined that the Iranian leader represented a turn toward beneficence and justice for Iran.

Famed French postmodernist philosopher and historian Michel Foucault, for instance, was seduced by the uncritical utopianism of the Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolution from its first days. Although Foucault would die in 1984 and not live to see the final draw of Khomeini’s fatwa bow, the philosopher openly supported the ayatollah’s movement in 1978 and 1979. Swept up by the promise of a new and supposedly just world—and revolted by the corrupt Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, whom the CIA and MI6 had idiotically conspired to impose on Iran—Foucault traveled to Tehran in the first months of 1979 as a reporter for French newspapers. These journalistic stints produced some of the most hallucinatory texts of an otherwise distinguished career.

Informed by a profound ignorance of Islam, and of Ayatollah Khomeini’s own writings more specifically, Foucault breathed into his reporting the revolutionary aspirations of the French left, which at the time was still looking for a “Third World” revolution worth backing. Foucault’s writings on Iran drew heavy criticism from those in France who knew better, and understood that the new clerical rule of Iran was a dictatorship.

As the renowned French scholar of Islam, Maxime Rodinson, wrote of Foucault at this moment: “The great gaps in his knowledge of Islamic history enabled him to transfigure events in Iran, to accept for the most part the semi-theoretical suggestions of his Iranian friends, and to extrapolate from this by imagining an end of history that would make up for disappointments in Europe and elsewhere.”

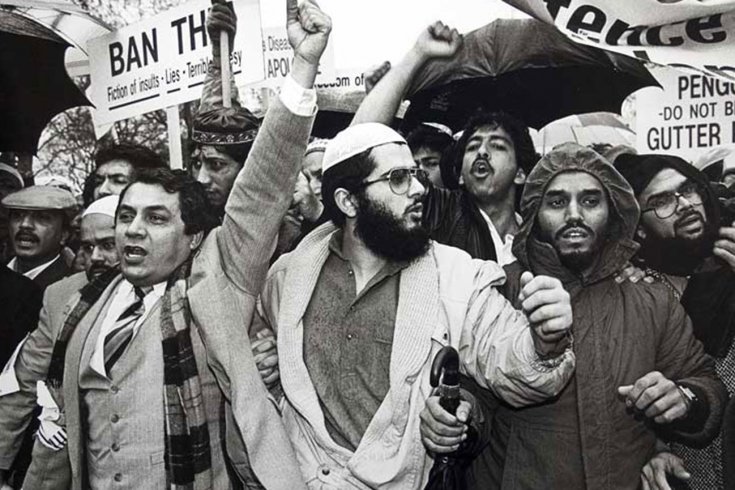

When Ayatollah Khomeini released his final, history-changing arrow on Valentine’s Day, even the most self-deluded European intellectual could not mistake his intentions for Cupid’s. Eight years of war with Iraq, the rise of the brutal theocracy and its thuggish Republican Guard, and the Iranian hostage crisis had clarified all this. But the power of the fatwa had been demonstrated on the international stage. The fatwa had been weaponized. Like a Cold War ICBM, it had the power to strike fear into the hearts of enemies continents away. History’s first intercontinental ballistic fatwa (ICBF) galvanized lynch-mob Islamic activists in the UK and elsewhere to support the ayatollah’s call for Rushdie and his associates’ heads. Rushdie’s Japanese translator was assassinated; his book was burned; people connected to any aspect of its publication were targeted. Rushdie went into a decade-long seclusion under the protection of Scotland Yard.

The full extent of the popularity of Ayatollah Khomeini’s ICBF was demonstrated when a British singer-songwriter once associated with peace, love, and understanding, Yusuf Islam (Cat Stevens before he converted to Islam in 1971) embraced it. At a nationally televised event in 1989, Yusuf Islam said that he would provide Ayatollah Khomeini with Rushdie’s location if he’d known it, and stated clearly that he would rather see the real Rushdie being burned rather than his effigies in the streets. (The singer later claimed that he was misunderstood, and that he was joking. But having seen the footage myself, I find it hard to take this defense seriously.)

Even Rushdie himself stumbled and apologized for his alleged offenses against the Muslim faith, and then briefly and publicly converted to Islam—a move he later deeply regretted and acknowledged to be a “stupid mistake.”

Meanwhile, other writers and politicians rallied in support of Rushdie. And for good reason. Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer put it this way, in a letter to the threatened author: “As for writers, we who are at special risk, the fatwa can never be distanced as something that happens to somebody else. With the powers of international terrorism at the service of fanaticism, northern and southern hemispheres are one hunting ground.”

Rushdie’s own 2012 memoir has clarified just how expansively and dangerously this “fanatical cancer,” as he called it, had spread to other Muslim communities. Reflecting back on the evolution of militant Islam during the past two decades, Rushdie cautioned that while Islamophobia must be resisted:

It was Islam that had changed, not the people like himself [meaning Rushdie], it was Islam that had become phobic of a very wide range of ideas, behaviors, and things. In those years and in the years that followed Islamic voices in this or that part of the world—Algeria, Pakistan, Afghanistan—anathematized theatre, film and music, and musicians and performers were mutilated and killed. Representational art was evil, and so the ancient Buddhist statues at Bamiyan [in Afghanistan] were destroyed by the Taliban. There were Islamist attacks on socialists and unionists, cartoonists and journalists, prostitutes and homosexuals, women in skirts and beardless men, and also, surreally, on alleged evils such as frozen chickens and samosas.

The situation has worsened steadily since that fateful Valentine’s Day in 1989. On this February 14, the stinging boomerang of the fatwa has come full circle. So, as we pick through our Valentine candy, select the right roses and gifts, and look through the cards in the grocery stores, let’s remember that it wasn’t always this insane. Yes, the fanatics have become more fanatical and the victims more numerous; we have gone from one murderous Valentine’s card—that first ICBF dispatched by an ailing Ayatollah Khomeini—to mass mailings of ICBFs by cocksure radicals.

And yet, paradoxically, despite the grave threat to free expression, the literary and artistic world has not retreated. So-called “Islamic” terrorism has produced more not less art by defiant artists. Terrorism has not achieved its principal goal, which is to force those threatened to self-censor and hide in caves. Hundreds of exiled writers continue to write in opposition to this kind of terrorism and refuse to be cowed by these radicals. More recently, evidence of this resistance was on display when many publications chose to reproduce the Charlie Hebdo cartoons following last month’s attacks in Paris.

As we think about the significance of all this, let’s take a moment to say “Happy Valentine’s Day” to Salman Rushdie and all the others menaced by terrorists. The battle for free expression will yet be won.