In a historical anomaly, Canada presently finds itself with some cultural cachet south of the border. Drake is often courtside for hometown Raptors games. Céline Dion is cool again. People seem to like that our prime minister isn’t trying to start any nuclear or trade wars. So it may be hard to remember that, in the early ’80s, American culture was not interested in Canada. At all. When our performers moved to New York and LA to work, they quickly dropped their accents. One of our biggest cultural exports of the era, Degrassi, didn’t try to obscure its location—and even then, American audiences tended to assume it was set in their very own Anytown. (“At that time, many productions in Canada changed licence plates on cars to be American,” says co-creator Linda Schuyler. “We kept the Canadian ones. We used real street names, and our kids travelled by the TTC.” But, nonetheless, according to Schuyler’s partner, Stephen Stohn, audiences thought the show took place in either Florida or California.)

It’s understandable. Why would any US entertainment company cater to a market with a population roughly one tenth of its own? No network sitcom ever felt the need to set a vacation episode in Montreal. The closest that globe-trotting James Bond came to Canada in any of his twenty-six films was flying over Newfoundland in Goldfinger. Except when our cities doubled as knock-offs of Chicago or Seattle, we did not see Canada in mass-market movies or television.

But we did in comic books. From 1983 to 1994, a generation of comic readers saw Canada, every month, in the pages of Marvel’s Alpha Flight: a series all our own, devoted to the tales of a team of Canadian superheroes enlisted by the federal government to help the nation fight (what else?) villains with superpowers. For many of us growing up at that time, this was confirmation of our country’s legitimacy. “It was surreal seeing the names of places I’d actually travelled to making their way into my favorite comics world—Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Halifax,” says comic-book writer and art professor Jim Zubkavich. “It just made the whole thing feel that much more real, to me, in a way that fictional cities like Gotham or Metropolis didn’t.”

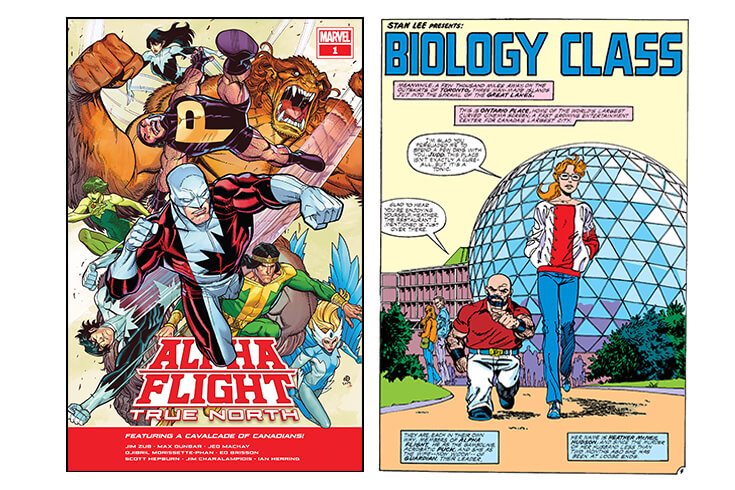

For a brief moment this fall, Alpha Flight is back. In celebration of the company’s eightieth anniversary, Marvel is publishing a one-shot, a single issue piggybacking on the Toronto Raptors’ NBA championship victory and the attention it’s drawn to this country. It is called “Alpha Flight: True North,” and Zubkavich is one of its writers. “Writing comics for Marvel now, as an adult, is a surreal experience,” he says. “I’m tapping into that same excitement I had when I was a kid, but also trying to do something new and . . . not make it purely an exercise in nostalgia.”

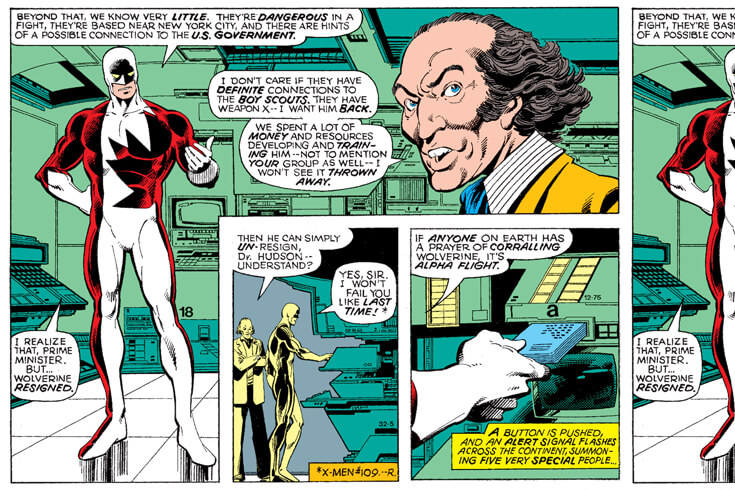

Alpha Flight’s journey to semi-stardom started in 1979, with issue 120 of The Uncanny X-Men. Title: “Chaos in Canada.” It opened with no less than Pierre Elliott Trudeau, the impatient prime minister demanding to know, in the first spread, what the military was doing to regain its costly investment in Wolverine, a special agent who had gone AWOL to join the X-Men. (The character was already a star of that series.) Details about Wolverine’s past were left intentionally cryptic; one of the only things we knew about him was that he was Canadian.

As a kid, unaware of the stability of our parliamentary system or the quality of our public health care, this was what made me proud to be Canadian. I wouldn’t learn until decades later that Alpha Flight’s Canadianness was a fluke, the outcome—to add insult to injury—of office politics gone wrong.

In the late 1970s, X-Men found itself enjoying a renaissance. Revived from cancellation in 1975, the comic had become Marvel’s most popular title under the guidance of writer Chris Claremont and artist John Byrne. The pair developed many stories together, and during their tenure, they collaborated on sagas—“Dark Phoenix,” “Days of Future Past”—so enduring that they’ve been adapted into movies and television shows several times over.

It was during this fertile period that the X-Men had a two-issue adventure in Canada: a battle with Alpha Flight at the Calgary Stampede. “Alpha Flight caused a bit of a stir among the readership when they debuted in those two issues of X-Men,” says Tom Brevoort, executive editor of Marvel Comics. “They were a bunch of cool new characters, all of whom gave off the [impression] of having more complicated backstories, and so readers were interested in seeing them again and learning more. So, for the next few years, they turned up here and there—an Incredible Hulk annual, issues of Machine Man, additional appearances in X-Men, etc. And that interest never waned.”

By 1980, the relationship between Claremont and Byrne had soured. It was, their colleagues remember, the usual kind of thing. “Chris was still having tremendous success on the X-Men with other artists,” recalls Jim Shooter, editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics from 1978 to 1987, “and I think John was a little jealous.” Claremont continued working on X-Men for a run that would last seventeen years, and Byrne began writing his own material separately. Byrne, Shooter says, “wanted to come up with a team book to be kind of like the X-Men but not, and he had Alpha Flight, which was largely his creation . . . I liked it. John was real enthusiastic about it. He’s a great talent—a tremendous artist and a very good writer. I thought he could do a good job at it.”

Byrne, who has a habit of declining media requests (including mine for this story), has repeatedly denied that he was interested in Alpha Flight. “When Marvel asked for an Alpha series, I resisted for a long time,” reads a statement on his website. “I just didn’t see much that could be done with them. They had no real depth, and I resisted suggestions that they get their own book for a couple of years. Then, finally, realizing Marvel would probably get someone else to do it if I didn’t, I relented and agreed.” The series would run for over ten years, its first twenty-eight issues written and drawn by Byrne.

But, in its creators’ minds, this new superhero team was never an appeal to Marvel’s Canadian fans: if Wolverine happened to have been AWOL from the Brazilian army or the Australian army, that’s where Alpha Flight would have been from. Byrne, quite blunt about this in an interview he gave when the series launched, in 1983, said that “if it were going to be a smash hit only in Canada, it wouldn’t be worth it. I think the group’s real popularity lies not with Canadian fans but with American fans, possibly because they are, I don’t know, slightly exotic, being Canadian. That’s foreign, and therefore out of the ordinary to the American fan.”

It was, in truth, just happenstance. In their first appearance, before anyone had a sense that the team would go on to anchor a separate series, the Alpha Flight characters were given just enough backstory—seen briefly in their secret identities, based in real places like Yellowknife or McGill University—to make readers want more. So, eventually, that’s what we got.

On page one of the first issue of Alpha Flight, the superhero team has been defunded and disbanded by Trudeau. Team leader James Hudson—eventually dubbed Guardian after running through a series of placeholder names that included (with various degrees of seriousness) Weapon Alpha, Vindicator, Captain North of the 49th Parallel, and Major Maple Leaf—stands in the empty shell of his Parliament Hill workplace, wondering what he’s going to do next. Soon afterward, the unemployed Hudson goes to New York for a job (moving to the States because of limited career prospects is as Canadian as it gets), and other members of the team go their separate ways for a full year’s worth of instalments.

Also part of Alpha Flight: Jean-Marie Beaubier (Aurora), who suffers from a split personality partially due to abuse she suffered at the hands of Catholic nuns. Her twin brother, Jean-Paul (Northstar), is gay, which was new terrain for 1980s-era comics. He also used his powers to become an Olympic skier—oh, and he’s a former member of a violent Quebec separatist group that bears a more-than-passing resemblance to the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). And then there are Sasquatch (a scientist from Vancouver when he isn’t in his superhero persona), Shaman (a healer from the Sarcee nation, which was later changed to Tsuut’ina to reflect the actual First Nation’s preferred name), and Snowbird (an Inuk deity who can “assume any shape at will” but primarily exists in the form of a Caucasian woman), who loses her powers outside of Canada’s borders. (More on her shortly.)

Unlike most team-based comic books, in which the characters work together, Alpha Flight is written as an ensemble, a collection of short stories with no main protagonist. (This was probably not intended as commentary on the Canadian psyche.) Perhaps because he cared so little about the characters, Byrne took huge conceptual swings with the series, telling stories that never would have been allowed with more canonical Marvel characters like the Avengers or the Fantastic Four (both of which he also wrote and drew over the course of his career). Issue six features multiple pages with no art at all, a battle in a snowstorm told only through sound-effect bubbles and dialogue. A chunk of issue eleven, meanwhile, has no dialogue. “In trying to distinguish Alpha Flight from all of the other team books that were then being published,” says Brevoort, “John looked for some narrative ground he could stand on that was a bit different . . . But John, at this point, was a powerhouse creator, and his presence alone gave the series good odds of performing well. So doing something a little bit different with the book wasn’t quite so much of a risk as it might otherwise have been.”

Shooter thought the whiteout sequence was clever and happily paid Byrne’s full rate for the blank pages, though he remembers the risk-taking as more a case of absentee editing. “I was the editor-in-chief,” he tells me. “I had fourteen editors working for me, so I wasn’t hands-on with every book. I couldn’t be. And John Byrne managed to seek out editors who would edit the least, in particular Denny O’Neil. Denny is a Hall of Fame–great writer. But, when he was at Marvel, he wasn’t even looking—he would sit there and do his freelance work all day. So John gravitated toward him because he then could do whatever he wanted. He didn’t even ask. Any crazy thing he could think of, he did it. And Denny never said no.”

From the outset, Byrne took advantage of Canada’s visual diversity and beauty, setting scenes in places like Banff or the Ontario Place theme park in Toronto. But he also took great liberties, referring to nonexistent attractions, like “Southbrook Mall” in Winnipeg, or—far more seriously—fabricating Indigenous deities.

These, unsurprisingly, were enough to prompt immediate complaints. A dismissive, unsigned response to them appeared in the letters page of issue four: “Some of our Canadian readers seem to have picked up Alpha Flight #1 in the mistaken impression that it was a copy of the National Geographic. Sorry people, but the intent of Alpha Flight is not to serve as a socio-economic/geography lesson on Canada. The Canada of Alpha Flight will be as accurate as, say, the United States of the Fantastic Four. Good enough?”

As the series progressed, representation of Canada was taken more seriously. The cover of issue fourteen, “What Lurks in Lake Ontario,” might have been an attempt to make up for the conclusion of the previous issue, in which Toronto is said to be located “along the shore of the mighty St. Lawrence.” Before a fight at the West Edmonton Mall in issue twenty-six, one of the characters offers up the trivia tidbit (then still true) that it’s the world’s largest shopping centre. (It has since been eclipsed by malls in China, Thailand, and the Philippines.) The series’ careless, stereotypical depiction of Indigenous characters, however, went largely unremedied.

For a lot of fans—like Adrianna Gober, an American who cohosts The Flight Stuff, a podcast about Alpha Flight—the series was most notable for introducing Marvel’s first gay hero. “My entry point into Alpha Flight was Northstar, who I knew from X-Men,” says Gober. “I wanted to learn more about the first openly gay superhero in mainstream comics, which prompted me to learn more about the history of Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Northstar’s checkered past as a former member of the FLQ was also enlightening . . . I had no idea about the Quebec sovereignty movement, or Canada’s broader sociopolitical history, until I started reading Alpha Flight.”

While Gober believes that the coded language in those issues would have been clear to any closeted youth, Northstar didn’t officially come out until issue 106 (1992). In 2019, no one would win a GLAAD award for creating an LGBTQ character who is also a terrorist and an Olympic-level cheater. But, in 1983, it counted as mainstream representation. The depiction of Aurora’s mental illness, likewise, was straight out of the 1950s—but, as a kid whose mother was in and out of mental hospitals, I was deeply attached to characters who had problems familiar to me.

Between the weirdness, the Canadiana, the X-Men associations, and Byrne’s popularity, the first issue of Alpha Flight did extremely well. Sales soon leveled off at about 300,000 monthly—still good, up there with The Amazing Spider-Man or The Avengers. But, Shooter says, this was far shy of X-Men’s 500,000 to 750,000, and after issue twenty-eight, Byrne left to write and draw The Incredible Hulk. Soon after that, he switched to DC to revamp Superman. After Byrne’s departure, sales drifted downward. “I remember handing John Byrne a royalty cheque for $30,000 (US) for that first issue,” remembers Shooter. “That’s good. But it fell. And I think John was disappointed that it did not sell like the X-Men.”

I didn’t start out knowing that Alpha Flight, which meant so much to me as a Canadian kid, meant something very different—maybe, in a way, something less—to its creator. But that, I’ve come to believe, is just fine. I know how it felt when I saw Northstar running down Queen Street (past the Silver Snail comic shop!) or Heather and Puck eating lunch at Ontario Place. It meant that Canada didn’t need sitcoms, or big-budget movies, or rock and roll. We didn’t need celebrities. We had superheroes.