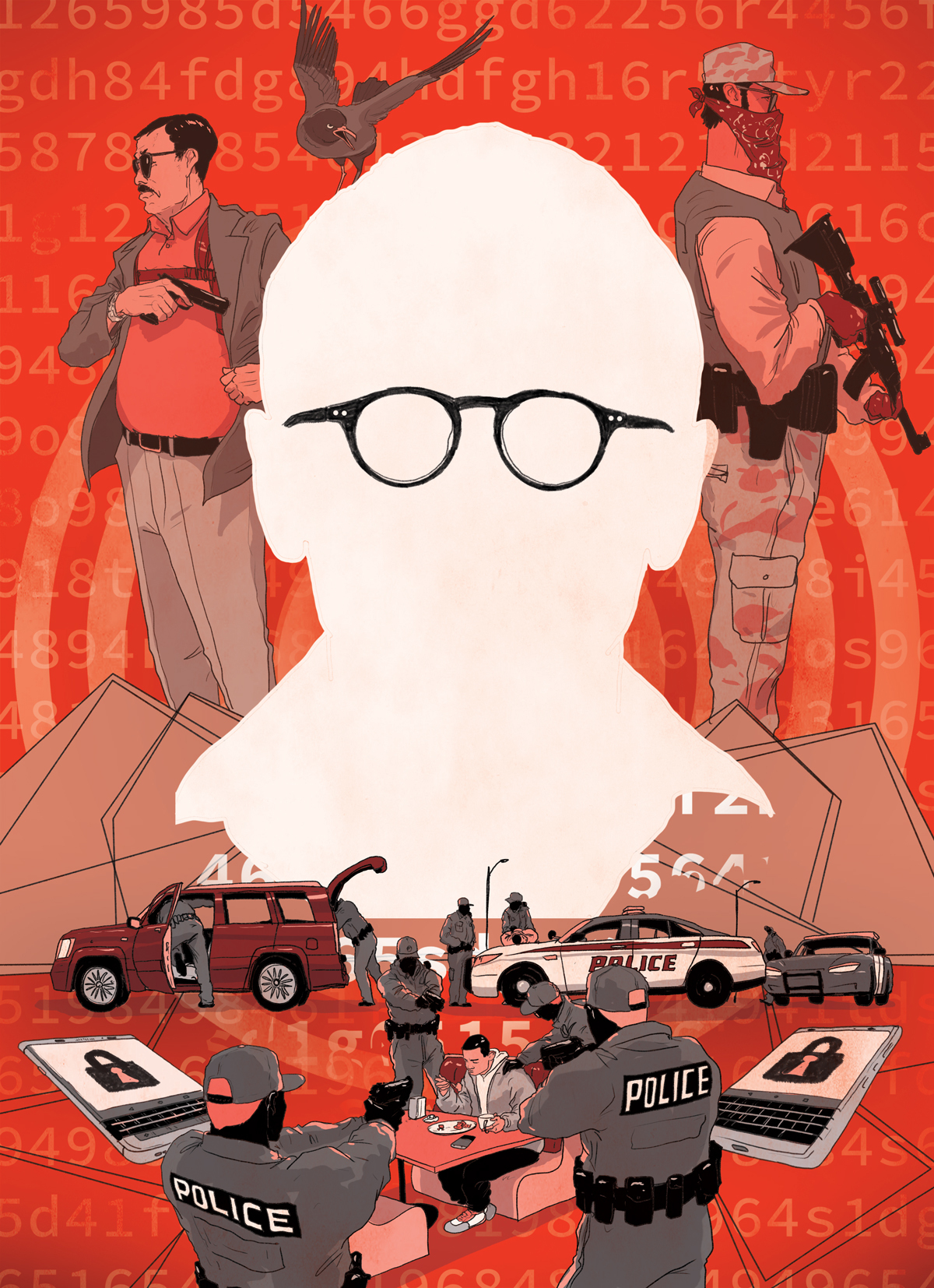

On March 7, 2018, Vincent Ramos was sitting alone at the Over Easy restaurant in Bellingham, Washington, just across the border from his home, in Richmond, British Columbia. He didn’t protest when a phalanx of cops marched in and arrested him. Speaking to the Bellingham Herald, the restaurant owner said Ramos “seemed like a mellow guy.”

It’s not mentioned in the account of his arrest, but the first thing officers likely did after they cuffed Ramos was reach into his pocket and grab his BlackBerry. That device, and the network it connected to, was at the heart of a sprawling FBI indictment that accused Ramos of racketeering activity involving gambling, money laundering, and drug trafficking. But that doesn’t quite cover the scale of his operation.

Ramos was founder and CEO of Vancouver-based Phantom Secure, a company that offered what it called “military-grade encryption” to criminal enterprises across the globe, from small-time loan sharks right up to Mexican drug lords. Fundamentally, Phantom Secure was a hardware company. It sold modified BlackBerry handsets that had been customized to communicate only with other Phantom Secure devices. On top of that, it ran an email system that routed encrypted messages through Panama and Hong Kong. As a result, conversations were nearly impossible to intercept, and if law enforcement did snag a message, there was no way of decrypting it. The FBI says as many as 20,000 clients signed up for protection that ran upward of $2,000 (US) for a six-month subscription. It even came with a customer service line. As a last safety measure, the company installed a remote kill switch, allowing phones seized by law enforcement to be wiped from afar.

Investigators had been watching Phantom Secure for some time. Police in different countries had been finding repurposed phones in stash houses and on suspects. But, by the time the devices were seized, they had been wiped clean and rendered useless. Police needed one with its data still intact. The year before Ramos was apprehended, agents at the Blaine, Washington, border crossing—just a half-hour drive from the Over Easy restaurant—intercepted an SUV loaded with twenty-five kilograms of party drug MDMA. The driver was carrying a Phantom Secure phone. Agents had, by then, developed an ingenious tactic: they would slip such phones into a Faraday bag, a specialized pouch designed to block outside signals. With the device cut off from its network, Phantom Secure would be unable to activate the kill switch. In this way, investigators used the information collected to build their case against the company. With each Phantom Secure customer they nabbed—drug dealers, mobsters—police got closer to Ramos. Eventually, they went after Phantom Secure itself.

By June, Ramos had turned state’s witness. As part of his plea deal, he handed over the login credentials for his servers, domains, and accounts, which gave police access to his entire operation. The technology was only one layer of protection, however. Ramos didn’t even know the identities of many of his clients. Police worked feverishly to untangle the complicated network of pseudonyms and code names gleaned from Ramos’s emails and messages. As word spread that Phantom Secure had been compromised, his co-conspirators began to disappear into the wind.

By then, investigators had already managed to disrupt the trafficking routes and communications structures of a litany of criminal gangs. It was a big score, though hardly the biggest. Drug busts happen all the time, and whenever the FBI knocks down a platform for a cocaine-smuggling operation, two more pop up. But investigators also came upon something unexpected, something that would shake the world’s largest intelligence-sharing partnership to its core. In Ramos’s emails, the FBI found a classified memo prepared by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The file had intelligence on Ramos himself, information that would have been invaluable in his attempts to elude investigators—information Ramos should never have possessed.

The list of individuals, worldwide, with access to such a memo wasn’t long. The discovery set off a mole hunt inside the upper echelons of Canadian national security that would lead to the Ottawa condo of one of the country’s most senior intelligence officials. In September 2019, the RCMP arrested one of their own: Cameron Ortis.

Situated in RCMP headquarters, the National Intelligence Coordination Centre is the analytic branch of the Mounties. Launched in 2013, the NICC helps keep tabs on the dark web and hackers both at home and abroad. It tracks international organized crime groups and biker gangs. It also monitors ideologically motivated actors, from terrorist groups to peaceful protest movements that could sabotage critical infrastructure. All this information is collected by RCMP officers in the field and blended with research provided by other intelligence arms of the Canadian government—agents at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), say, or at the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada. From that mass of data, NICC analysts and researchers produce reports that help set RCMP priorities, steer investigations, and inform on-the-ground policing.

At the time of his arrest, Cameron Ortis had been running the NICC for three years. There was a lot to keep him busy. During his tenure as director general, Islamic State militants had proven themselves adept at using social media to recruit and radicalize disaffected youth. Online black markets, like Silk Road, grew to popularity by offering everything from rocket launchers to heroin. Predators had moved away from the global internet and had begun sharing and selling child pornography on private servers.

The NICC wasn’t just producing intelligence reports for the RCMP—it was also distributing them to its partners around the world. After the Second World War, Allied nations banded together to share information in hopes of preserving a fragile world order. Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand became the Five Eyes. The partnership started out as a military pact but expanded to tackle cybercrime and terrorism.

Information that circulates around the Five Eyes is the sort marked “top secret”—it can be seen only by officials with the proper clearance. Getting that clearance is no small feat. Security officials will scour a candidate’s social media accounts, interview friends and family, and dig into tax returns and bank records. Areas of concern include money troubles or addiction issues—anything that could cause someone to be blackmailed or lead to their loyalty being compromised. The last time Canada reported statistics for security classification—1998—around 2,000 people a year were being granted top secret clearance.

Technology, Ortis felt, was giving criminals a door to a universe far removed from the prying eyes of law enforcement, and police needed to adapt.

After joining the RCMP in 2007, Ortis passed his security vetting and was hired as a strategic analyst—“a sort of jack of all trades,” as one of his former colleagues told me. Ortis was a rarity in the organization. He wasn’t, like his bosses, a cop. He was, first and foremost, an academic, having recently completed a PhD at the University of British Columbia, where he studied the intersection of technology and crime. Ortis wrote dense, thoughtful papers on how governments, primarily in the Asia-Pacific region, were failing to take seriously the threat posed by internet-literate criminal organizations. Drug cartels, anarchists, hackers, doomsday cults—all were using the World Wide Web, barely a decade old at that point, to organize and carry out nefarious deeds. Technology, Ortis felt, was giving criminals a door to a universe far removed from the prying eyes of law enforcement, and police needed to adapt.

But the digital world of the early 2000s was patrolled largely by troops and spies. The National Security Agency, in America, and our own top secret electronic-surveillance outfit, the Communication Security Establishment (CSE), were both branches of the military. CSIS, which investigates threats to Canada’s safety, focused on the internet only insofar as it was being used by terror groups and radical elements, whose ranks it sometimes tried to infiltrate. The RCMP, however, had long been frozen out of the national security game thanks to a string of screw-ups and ethically dubious activities in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Government investigations found that, during the 1970 October Crisis, the agency had, in the name of collecting intelligence, done everything from stealing documents to attempting to plant dynamite on suspected radicals. The reports led Ottawa, in 1984, to cleave off the RCMP’s national security work into a new body: CSIS.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks reinvigorated the Mounties’ zest for national security work. While CSE could intercept communications and CSIS could recruit informants and moles, they needed the RCMP to make arrests and obtain search warrants. But years out in the cold had left the force with an acute skills shortage. That became apparent pretty quickly. Just months after 9/11, the RCMP started up an investigation into roughly half a dozen Canadian citizens over their supposed ties to al-Qaeda—among them was an engineer named Maher Arar. The unfounded conclusions linking Arar to foreign terrorism were eventually shared with the FBI, which led to his arrest, rendition to Syria, and torture. In 2006, a scathing review found no evidence that Arar was involved with overseas terror groups and concluded that the RCMP “lacked the expertise to conduct national security investigations.”

Part of the RCMP’s problem was its personnel. Mounties were trained to be cops, not intelligence analysts. They may have been given some basic grounding in counterterrorism strategies but not much more. To address its shortcomings, the RCMP began scouting for non-officers skilled in digital forensics who could comb through web forums, Usenet groups, and chat rooms to, as per a 2004 job posting, “identify criminal trends and patterns.”

Ortis, who joined the RCMP the year after the Arar inquiry released its findings, seemed a perfect fit. As an academic, he believed it was a mistake to hand the cyber domain over entirely to soldiers and spies. Criminals and organized crime networks, after all, were the earliest and most eager adopters of new technology—and that, he argued, made the internet police business. And it was a business he seemed remarkably good at. He struck many of those around him as “super competent.” Overconfident, maybe, but as one former colleague frames it, Ortis was “no more arrogant than any other mediocre white dude in the public service.” Working within any government system has its fair share of challenges and headaches, but coworkers say handling internal processes was part of Ortis’s skill set. Less than a decade after joining the force, he became director general and, as has been widely reported, had a close relationship with then RCMP commissioner Bob Paulson. It was an undeniably quick rise, especially for a civilian in a system of skeptical cops.

Maybe more skepticism was warranted. Investigative documents from Ramos’s trial, and sources in the Canadian security world, point to Ortis as the origin of the sensitive documents that wound up in Ramos’s email. It’s still unclear just what else Ortis is alleged to have stolen and sold, but as director general, he would have had access to the most sensitive details on investigations by all Five Eyes countries. “He had a lot of leeway,” a former coworker says. His access would have been invaluable to foreign governments, such as Russia’s and China’s, which have engaged in long-running cat-and-mouse games of espionage with the Five Eyes—Moscow frequently looking for kompromat on Western politicians, Beijing often looking to steal commercially valuable information from private industry. It would have been worth plenty to foreign terror groups that regularly find themselves infiltrated by undercover operatives. And it would have been incredibly useful to international criminal outfits, whose phone calls and emails are often intercepted, to know which channels were safe. Whatever Ortis allegedly took was enough, according to the Canadian Press, to have CSE call the breach “severe.”

The charges against Ortis hint at his alleged crimes. Court documents claim that, in the winter and spring of 2015, he communicated “special operational information” to “V. R.”—believed to be Ramos. But it is also alleged that he communicated “special operational information” to “S. H.,” “M. A.,” and “F. M.” According to Global News, one of those sets of initials likely belongs to Farzam Mehdizadeh, a currency trader who, the RCMP believes, was connected to a multibillion-dollar money laundering organization that secured cash for Hezbollah, Mexican drug cartels, and many groups in between. Investigators believe Ortis contacted one of Mehdizadeh’s business associates, Salim Henareh (likely “S. H.”), offering information on the RCMP investigation in exchange for cash. All told, Ortis is facing ten charges under the Security of Information Act and the Criminal Code, which allege he stole classified information, attempted to cover his tracks, and communicated the information to a foreign entity or terrorist group. Taken together, these crimes could carry a lifetime prison sentence.

Investigators appear to have executed their first search warrant related to the leaks in the summer of 2018, soon after Vincent Ramos began cooperating. Over nearly two years, the courts authorized more than two dozen warrants, searches, and tracking devices in British Columbia and Ontario. They called it “Project Ace.”

Maybe this whole saga could have been avoided had the RCMP only familiarized itself with Ortis’s academic work. Reading his PhD thesis, it’s hard not to see foreshadowing of what he would, eventually, be accused of doing. He notes, for example, that in the late 1990s, the Pentagon faced down an extensive effort to steal sensitive military information from its servers. The hack, dubbed “Moonlight Maze,” exposed that not even the world’s most hardened cyberdefences could protect against dedicated individuals. Indeed, in his field research, Ortis writes that “government officials from two other countries acknowledged similar cases of serious breaches against military or highly sensitive research sites—some originating internally via a ‘trusted insider.’” More than a decade after writing that paper, Ortis would be charged with being the very “trusted insider” he warned about.

We know now, of course, that there were signs—disturbing behaviour by Ortis repeatedly flagged to RCMP higher-ups. After his arrest, three former colleagues filed a lawsuit accusing Ortis of reigning over a dysfunctional and toxic workplace, even telling one of them their work was “horrible” and “garbage.” The allegations, which have not been proven in court, claim that Ortis “systematically targeted them and attacked their careers as part of a larger plan to misappropriate their work and use it for personal gain.” Dayna Young, one of the analysts suing the RCMP, alleges that some of the intelligence Ortis tried to sell was, in fact, hers. The employees say they went to the RCMP with their concerns multiple times, but nothing came of it.

In February, Global News reported that an RCMP superintendent named Marie-Claude Arsenault had joined the lawsuit, claiming that, when she worked under him in 2016 and 2017, Ortis’s “bizarre and alarming behaviour” caused her to suspect he was trying to “deliberately sabotage” RCMP intelligence. She claimed to have repeatedly warned her superiors and was eventually transferred out of the NICC, which Ortis headed.

It’s still an incomplete picture. Ortis stood at the top of his field, not struggling on the middle rungs. Why risk it all? In his book The Anatomy of a Spy: A History of Espionage and Betrayal, Michael Smith describes four main motivators for going rogue: lust, money, ideology, and revenge. Ortis fits awkwardly into those categories.

Lust is a powerful motivator. The East German Stasi was said to be particularly adept at the honeypot—using romantic entanglements to encourage secret holders to betray their countries. Over the course of the Cold War, some forty women were prosecuted for slipping state secrets to their lovers, who turned out to be spies working for the Soviets. Those who knew Ortis, several of whom spoke to the National Post, suggest that, for all or most of his time at the RCMP, he was a workaholic bachelor. With its long hours, his career seems to have left little time for dalliances with, say, Russian diplomats.

Ideologically driven espionage tends to line up with a cause. Daniel Ellsberg, the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers, stole government documents in the hope that they would end the Vietnam War. Ortis, on the other hand, didn’t seem to have any discernible politics. “I can tell you what I told the RCMP: if he was extreme in his beliefs in any way, I certainly would remember, and I don’t remember any such thing,” says Tom Ngi, a fellow student who wrote code that helped Ortis analyze data for his thesis.

Espionage also pays well. CIA case officer Aldrich Ames made some $2 million (US) by selling secrets to Moscow in the 1980s. He began betraying his country because he was drowning in debt but ended up getting caught by amassing an unexplained wealth. If Ortis was desperate for money, there are few indications of it. His salary, as a senior intelligence official, would have likely been in the six figures. According to reporting, he dressed smartly and liked dining out, but he also rented sensible accommodations in Ottawa’s Byward Market. And his career prospects were hardly stunted. As Ngi noted, he could have made orders of magnitude more money in the private sector.

Then there’s revenge, often stemming from professional or personal dissatisfaction. FBI special agent Robert Hanssen spied for the Soviets for more than a decade, compromising the identity of countless American agents in the USSR, until the fall of the Berlin Wall. While his betrayal paid well, Hanssen would later confess he felt “rage” at having been passed over for promotion at the bureau. It’s hard to imagine that Ortis—one of the golden boys of the RCMP—would have been frustrated with his employer. His ascension through the ranks was remarkable.

In the end, it may not make sense to psychoanalyze his actions. Ortis was brilliant, wasn’t shy about it, and appears to have been caught selling secrets to the very type of criminal organization he was tasked with investigating. Maybe there’s no great explanation of why beyond the fact that he simply did. Maybe the sport was in the game, regardless of what side he was playing for.

Ortis’s alleged crimes, however, do point to a fundamental problem with the RCMP: how it investigates its own. Any department that handles top secret material is required to do regular checks of staff with security clearance. CSIS, for example, conducts polygraph tests at five-year intervals. One former intelligence official told me, flatly, that the RCMP’s internal processes are “not as good as they should be.” Indeed, an audit of the agency’s personnel security-screening process, published in 2016, found it “not sufficiently rigorous.” And, while it has a Truth Verification Section—a unit dedicated to particularly difficult interrogations of suspects and witnesses—the RCMP seems to have generally been negligent about vetting its own staff.

Employee reviews, however, are only one way of probing for weaknesses. Robust security protocols also demand regular auditing of classified information. When Ortis’s residence was raided, investigators found dozens of encrypted computers, according to the CBC. While it’s not known yet what these computers held, taking any sensitive documents home is enough to raise eyebrows. According to a former intelligence official, it’s generally uncommon to leave the office with files marked secret. To walk off with anything top secret is strictly forbidden. Such files are typically accessed only in a SCIF—short for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility. It’s a room where cellphones, laptops, or any other devices are prohibited and where walls are usually reinforced to prevent electronic eavesdropping. To prevent breaches and theft, security agencies are also supposed to keep precise records of who handled what classified assets when. These safeguards are standard for all Five Eyes and most NATO countries, given that a large portion of top-secret material is a blend of intelligence from various international agencies. If one agency is lax, it could expose the secrets of allies.

Which is why the Ortis affair is such a calamity for Ottawa and the spy bosses on Ogilvie Road, where CSIS and the CSE are headquartered. The fact that the breach first happened some four years before Ortis was arrested is especially embarrassing. (Compare it with other leakers from the digital era, such as former US Army private Chelsea Manning or ex-Air Force intelligence officer Reality Winner: each exfiltrated sensitive information with ease, yes, but each was promptly identified.) If a partner in the alliance can’t be trusted, it may weaken the vital openness of the Five Eyes partnership. Such moves could inspire countries to withhold material.

Canada has had a few of these embarrassing high-profile episodes. But so have its allies. Most notably, in 2013, National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked thousands of top-secret documents about the US government’s surveillance methods. In 2017, Wikileaks released details of the CIA’s Vault 7, a database of powerful hacking tools. One of the most effective strategies after a leak, according to a former intelligence official, is the rather cynical practice of saying “maybe you tomorrow.” That is, you remind other agencies that they, too, have had leaks. And they will likely have more. It was Canada today, but it may be you tomorrow.

That strategy only goes so far if Canada can’t prove that it’s taken significant steps to address security deficiencies. RCMP commissioner Brenda Lucki has insisted that “mitigation strategies are being put in place”—presumably to avoid another Ortis. What those strategies are, however, Lucki hasn’t said.

Cameron Ortis’s story tells us a lot about insider threats at the government agencies designed to protect us. But, if the charges against him are true, his story also tells us an enormous amount about the value of in-depth, investigative policing.

In February, CSIS director David Vigneault gave a virtual address to the Centre for International Governance Innovation, warning that “any individual with inside knowledge of—or access to—an organization’s systems can be targeted by hostile intelligence services.” He told the audience that the “significantly more complex environment” necessitated more powers for CSIS “to use modern tools.” It’s a variation of what the RCMP has also long lobbied for. In 2016, then commissioner Bob Paulson warned that “the single most important issue we have” was the threat of “going dark”—referring to the ability of criminals to hide behind strong encryption standards. Indeed, Canada is joining a chorus of national security agencies in other Five Eyes countries that have pushed for ever-broader powers to outlaw or weaken these encryption standards in order to better hunt down criminals everywhere.

One threat of particular concern is something called Pretty Good Privacy, or PGP. Over the years, PGP has become the bedrock of modern encryption—it was the foundation of Phantom Secure—and has influenced the technology used to scramble data in WhatsApp, Signal, iMessage, Wire, and a host of other popular messaging clients. The concept is rather simple: PGP gives anyone, through a series of equations, the ability to generate a string of letters and numbers—a key. That key, a version of which is uploaded publicly, is used to encrypt any message or file the user wants. A whistleblower, say, may want to contact a journalist securely. To do so, they may use the journalist’s public key. The journalist, in turn, can read the message only once they unlock it with their private key.

While we know that security services in Canada and abroad have figured out all manner of hacks to beat commercial encryption, PGP remains more or less secure. In his thesis, Ortis predicted what would happen when criminals have privacy defences that outpace the investigative methods available to police. “Faced with a quickly evolving predator,” Ortis wrote, governments will try to turn the tables with “more police and more laws and, possibly even framing the problem as a threat to ‘national security.’”

Some governments have tried exactly that. Singapore has long given its police agencies the power to force citizens to decrypt their communications. In 2018, Australia passed a bill requiring technology companies to decrypt any messages sent on their platforms. While the full impact of that law hasn’t yet been felt, the Guardian has reported that Australian police may use their new powers to snoop on McDonald’s free Wi-Fi or on citizens’ online-shopping habits.

As governments spend more time worrying about how to crack encrypted communications, the most effective way for them to combat digital criminals—even in their own ranks—continues to be low tech.

But, as Philip Zimmermann—who invented PGP—told me recently, fighting against encryption and against the evolution of technology is like trying to force Henry Ford to limit the size of his cars’ engines in order to stop Bonnie and Clyde. It’s “a fool’s errand.” And Ortis’s own arrest shows why. During the years the RCMP spent trying to convince the public it needed expansive new legislative powers to do its job, its top brass was allegedly spiriting away its secrets to a criminal encryption company.

Ortis wasn’t fatalistic about the threat that cybercriminals pose in a world with strong encryption. Far from it. He argued that police agencies too often treat the internet as “a kind of black-box.” As governments spend more time worrying about how to crack encrypted communications, the most effective way for them to combat digital criminals—even in their own ranks—continues to be low tech. Tactics used in effective online investigations aren’t all that different from how cops bust drug rings or organized crime groups in real life. It was, after all, a Faraday pouch—a bag lined with aluminum—and the capture of a cyber kingpin that ultimately led to Ortis himself. Good police work, not draconian laws, dismantles criminal enterprises. Ortis was right. So right that he may go to jail for it.