Indian prime minister Narendra Modi is a hugger. The political strongman has been wrapping his arms around world leaders since coming to power four years ago. The displays are brazen and, for some Indians, embarrassing. But when Justin Trudeau first stepped off the plane on his trip to India last week, Modi was nowhere to be seen, and instead, the Canadian prime minister found himself being greeted soberly on the tarmac by a junior-level agriculture minister.

“Snub” was the word that immediately appeared in the press. Indian officials say Modi’s no-show was diplomatic protocol, yet he did greet, on their arrival in India, then US president Barack Obama, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, and Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It wasn’t hard to attribute Modi’s possible rebuff to the perception that the Canadian government was indulging Sikh separatists within its borders. Indian politicians criticized last year’s motion in the Ontario legislature to call the 1984 anti-Sikh riots in India a “genocide.” The motion was brought by a Liberal Party member, and one senior Indian official was quoted in the Hindustan Times saying that if Trudeau and his team “can’t manage their own party…they have to own the responsibility.” Less than a month after the motion passed, Trudeau appeared in Toronto, donning an orange head covering at an event that reportedly featured not only flags of Khalistan, the dreamt-of independent Sikh homeland, but posters of Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the revolutionary who Sikhs consider a martyr and the Indian government calls a terrorist.

Trudeau’s outreach to Sikhs—Canada being home to their largest diaspora—is an expected part of the Liberals’ all-inclusive, fair-weather posturing, but in India, this comes with a cost. Sectarian sentiments are not something you want to underestimate in a nation as divided along religious lines as India is under ultra-right Modi—especially if you’re someone whose global brand relies on the premise that you’re the leader of a progressive, multicultural country, a woke politician who “gets it.”

I lived and worked in India for almost a decade, until the end of 2016, and consider the country one of my homes. From Mumbai, I watched Trudeaumania 2.0 spread and saw young Indians—along with everyone else on the planet—swoon. That bhangra video from the India Canada Association of Montreal, filmed before Trudeau became PM, caused all my female Punjabi friends to sign up with Team Justin. He was hip, he was feminist, and he wasn’t like Modi. In January 2016, I wrote a satirical open letter to Canada for GQ India, beseeching my homeland to stop making the rest of the world look bad. Months later, there seemed to be a shift in the English-speaking world order. The sun was going to set on Britain, thanks to Brexit, and Donald Trump had just begun to show how absurd his presidency was to become. Meanwhile, Canada was considered cool. What the hell happened? Substantially, not that much. But, visually, mostly Justin Trudeau. Canada finally having its moment was all too good to be true, and I waited for the day this social-media fever would break.

Trudeau’s disastrous visit may be that moment, at least in India. Trudeau, who boasted in 2016 he had more Sikhs in his cabinet than Modi did, miscalculated the extent to which India’s political class loathes the idea of Khalistan—Stephen Harper, for the most part, avoided appearing separatist-friendly to his Indian counterparts—but Team Trudeau’s diplomatic dereliction involved far more than throwaway sound bites.

For example: inviting Jaspal Atwal, a former member of an illegal Sikh separatist group, who was convicted of the attempted murder of an Indian politician in British Columbia in 1986, to an event at the High Commission of Canada in India, in New Delhi. The invitation was rescinded, but Atwal had already managed to pose for a photo with Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, among other members of Canada’s retinue, at a different event in Mumbai. As Trudeau’s fawning youth base might have hashtagged, #YouHadOneJob. One journalist described Trudeau’s visit as “a total disaster,” and she was the one being nice.

Most frustratingly, there seems to have been no pressing reason for the state visit, which led to accusations that the whole thing was a Liberal exercise in Punjabi vote banking back home. The most urgent trade issue between the two countries is India’s new tariff structure on Canadian pulses. It’s a clear disadvantage for our pulse farmers but hardly requires high-level diplomacy. Instead, we got cringe-inducing images of the Trudeaus traipsing around the subcontinent on a multi-state, technicolour-dreamcoat tour. The internet being the internet, Trudeau’s costume changes got more play than his fence-mending with Punjab chief minister Amarinder Singh, a vocal opponent of Sikh extremism, diaspora separatism, and Canada’s attitude to both.

Trudeau lorded it up like pre-independence wedding royalty by swanning around with Bollywood stars and feigning prayer-handed piety at temples. The level of scrutiny paid to his sherwanis over his statecraft proves that matters of his celebrity still eclipse matters of government. Maybe he feels it, too, and is trying to draw out what was, not so long ago, a winning, viral formula. Justin even reprised some bhangra steps at one of his trips’ last events. As everyone but him could have predicted, social media piled on all the more.

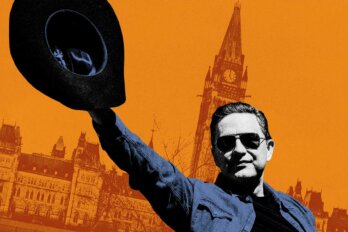

If Trudeau’s not careful, this trip could be remembered as the first step of a steep decline, one rushing towards him at fibre optic speed. India has the world’s largest youth population, hence a huge number of observers who will either love or hate him depending on the way he speaks to them on their screens. While bad Indian press won’t, in itself, have a substantial effect on Trudeau’s brand, what hurt was how the rest of the world watched him become a laughingstock—and joined in. It proved how easily the Instagrammable global connectivity Trudeau has embraced can be used against him.

Trudeau did eventually get a hug from Modi, on Modi’s terms and at the time of Modi’s choosing. But in terms of Trudeau’s incredible streak of governing by social-media cred, there would be no Twitter redemption. I used to joke to my Indian friends that among the set of emojis in various skin tones, the smiling white face in the turban was secretly made for Justin Trudeau. They would shake their heads. “Don’t be an idiot, Dave. No one even likes that one.” Turns out that flat-grinned emoji may be far more like Trudeau than I’d imagined.