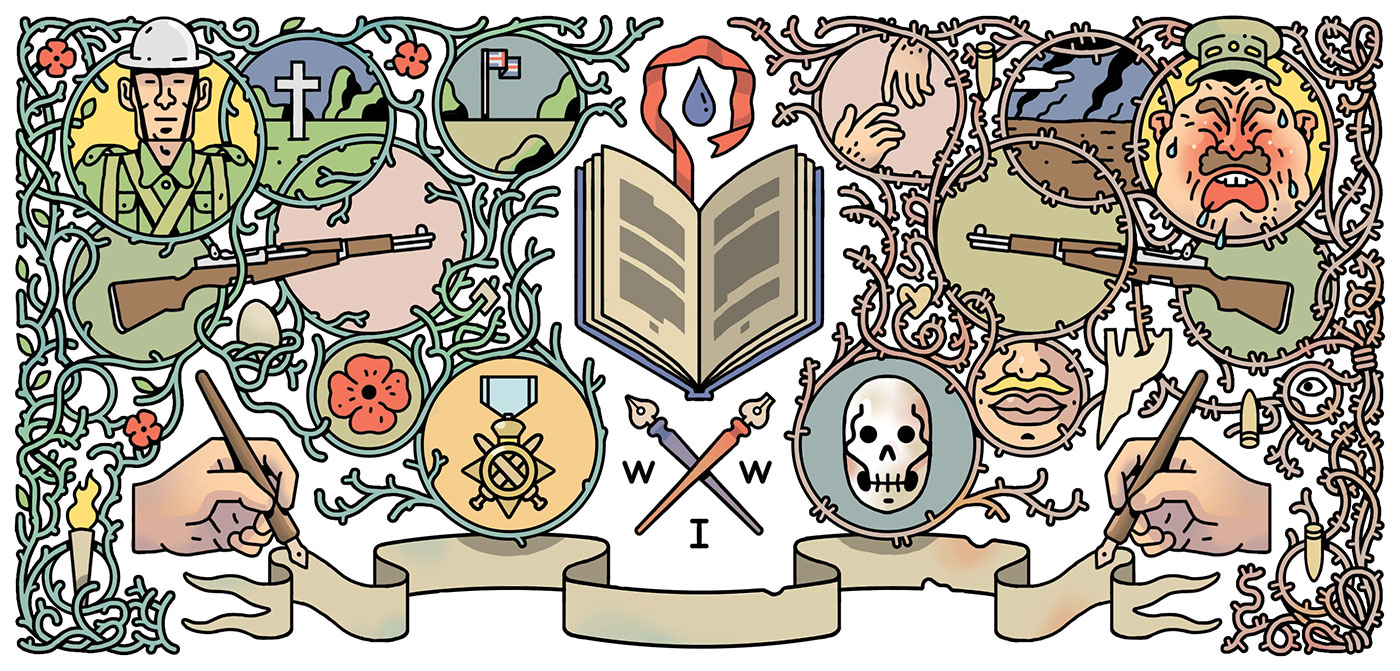

Under Discussion

Goodbye to All That (1929)

Robert Graves

The Wars (1977)

Timothy Findley

Regeneration (1991)

Pat Barker

Open Secrets (1994)

Alice Munro

World War One British Poets (1997)

Candace Ward, editor

Three Day Road (2005)

Joseph Boyden

It is the victors who write history. Winston Churchill knew that history would be kind to him, because he intended to write it: he released the first volume of his account of World War II in 1948, a mere three years after seeing the Allied war effort in Europe to a successful conclusion. With literature, though, it’s more complicated.

The world war before Churchill’s, the so-called Great War, broke out 100 years ago this summer. Even now, even here, it looms large. The Canadian War Museum in Ottawa lists close to 61,000 fatalities—nearly 1 percent of the young nation’s population. The slaughter of 16 million was unprecedented, with rapidly industrializing nations using so many just-invented weapons. Yet there was an intimacy to World War I: the enemies could often see one another, and they famously played soccer in a sliver of no man’s land one Christmas. This war was also muddier, both literally and morally, than the fight against the Nazis, making it an excellent subject for literature.

I was introduced to the epoch, as so many are, through All Quiet on the Western Front, the 1929 novel by German soldier Erich Maria Remarque; and Canadian brigade surgeon John McCrae’s 1915 poem, “In Flanders Fields.” But for all of the larks singing, torches passing, and red poppies blowing, neither work moved me. It took The Wars—Timothy Findley’s angry, sexy book—to ignite my obsession. The novel had much to recommend it to a boy of seventeen growing up in boring, suburban Oakville, Ontario. There was plenty of sex in the 1977 novel, much of it, in the pre-Internet age, of that hard-to-find gay kind. This mattered because I was struggling to figure out how to deal with a growing inward certainty that I was gay.

Findley puts the troubled, gentle son of a prominent Toronto family into the trenches, and I was intrigued that the protagonist shared a name with one of my ancestors, Robert Ross, another man who didn’t survive the war. News reports suggested that Findley had named his character after my ancestor, and I was curious to know why. In an attempt to make sense of the puzzle of the two Robert Rosses, I read everything I could about the period, and stumbled upon something we would now call a culture war. It questioned old notions of honour, valour, masculinity, and the very justice of what was happening in the trenches.

On a ship heading across the Atlantic toward the war, Findley’s Ross shares quarters with another young soldier, who is reading the works of G. A. Henty, the prolific Victorian novelist who wrote about how young men ought to behave under fire; manuals about how to be a man, with such titles as With Wolfe in Canada: Or the Winning of a Continent and By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War. Henty’s young men risk much, and they also respect the commands of their leaders.

Many of the books that came out of World War I, including Findley’s, radically departed from Henty’s hurrah-for-the-Empire world view. So did the real Robert Ross. Though he was the grandson of Robert Baldwin, the moderate Upper Canadian politician, he lived in England’s capital for most of his life, and was a friend and mentor to many of the literary soldiers who became known as the war poets. They, too, were as anti-Henty as possible, and openly challenged the meaning of the war.

To find out about my Robert Ross, I made research trips to London and his alma mater, Cambridge. I reviewed family papers and visited with a relative who had ended up in the Black Forest of Germany, and I learned that the real Ross was gay. Finally, I had a ghost in my corner.

He had lodged with Oscar Wilde while cramming for his university entry exams, and the two men reportedly became lovers. The scandalous affair died on the vine, but the friendship survived.

Ross came into his own after Wilde died, finding love for a time with a young actor and helping to run a gallery in Chelsea. Under his tenure, it exhibited work by such artists as Auguste Rodin, Aubrey Beardsley, and John Singer Sargent; and a daily asked him to write a column on visual art. All the while, as Wilde’s literary executor, he worked hard to resuscitate his disgraced friend’s reputation.

By 1913, it looked as if he had pulled off a coup: Wilde was starting to be read again, even in England, and Ross’s own social stock soared. One of his great friends was Margot Asquith, the prime minister’s wife, and he could call the likes of Henry James, H. G. Wells, and Thomas Hardy chums. That year, he met Siegfried Sassoon, a well-to-do aspiring poet more than twenty years his junior. In 1915, the younger man dutifully went to war and won the Military Cross; he took to spending his leaves at Ross’s rooms in Soho. Where Sassoon’s early poetry about the war is elegant and elegiac, his later work becomes more satiric, some of which is down to Ross’s influence.

Ross hated the war. A nephew of his, as well as Wilde’s first-born son, died early on. He became increasingly incensed at the conduct of military leaders who used obfuscating jargon to summarize the heartbreaking human losses, recognizing in them the same sorts of muscular Christians who had taken down Wilde. He ranted to Sassoon about the “screaming scarlet majors” running the war effort, and the acidic, anti-authoritarian phrase made its way into one of Sassoon’s best-known war poems “Base Details.” (Sassoon wisely cut “screaming.”)

Perhaps inspired by Ross or his pacifist friends (among them Bloomsbury groupies Lady Ottoline Morrell and Bertrand Russell), Sassoon decided to send his superiors a fierce anti-war statement in 1917, refusing orders to return to the front. He sent a copy to Ross, who was horrified at the court martial that probably awaited Sassoon, and immediately mobilized a mutual friend, Robert Graves, to ask that the authorities treat the statement as a symptom of a mental breakdown. Pat Barker’s 1991 novel, Regeneration, tracks the course of Sassoon’s therapy at a mental hospital in Edinburgh.

Meanwhile, Ross faced troubles of his own. Not everyone was happy with his social rise. Lord Alfred Douglas, for whom Wilde had risked and lost so much, was now married and embarrassed about his famous affair with Wilde. He joined forces with a tabloid journalist and poet named T. W. H. Crosland to take Ross down. They published withering attacks on him, questioned his patriotism, and kept reminding readers of something most preferred to ignore: that Ross was unapologetically gay. He promptly resigned as the Board of Inland Revenue’s assessor of pictures, to avoid bringing disrepute to his office.

Crosland’s wartime verse was bargain basement Kipling: “Lo, the stark heavens are stirred: / He cometh, plumed and spurred, / To say the undaunted word, / England!” Sixteen stanzas end with said undaunted word. At the time, such ultra-patriotic verse was hugely popular. The English poet laureate Robert Bridges’ paean to one of the supervisors of the war effort, Lord Kitchener (“Unflinching hero, watchful to foresee…”) is the literary antithesis to Sassoon’s poetic critique of the scarlet majors.

Midway through the war, a renegade Member of Parliament named Noel Pemberton Billing announced that he knew of a long list of traitors held by the Germans, and he implied that Ross was high up on it. The accusations were wild: the female traitors, including the prime minister’s wife, were said to be distinguished by their engorged, enormous clitorises. An actress sued Billing, and Douglas testified on the MP’s behalf, using the immunity of the witness box to attack Ross—and the cult of their shared lover, Wilde.

Despite the outrageousness of Billing’s assertions, he was exonerated in a wave of patriotic hysteria. Ross found the campaign against him deeply upsetting, and his health, never good, took a turn for the worse. Toward the end of the war, at age forty-nine, he died of heart trouble. About his mentor, Sassoon later said, “It seems reasonable to claim that this was the only occasion on which his heart failed him.”

The battle over what World War I meant, and who would write its meaning, continued long after Ross died and the war had ended. The culture war eventually saw the anti-authoritarians defeat those working the Henty vein, giving rise to the now-familiar narrative of an idyllic, ordered society—Downton Abbey—ruined in five foul years. This was the vision promulgated in the poetry of Ross’s young proteges—the so-called war poets, Sassoon and his friends Wilfred Owen and Graves. Along with his free-thinking classical poems, in 1929 Graves wrote a trench memoir, Goodbye to All That, which shows a gallant, God-loving world destroyed by the war. Owen concludes his most famous poem by attacking what he calls “the old lie: Dulce et decorum est / Pro patria mori”—that is, roughly, how sweet and glorious it is to die for one’s country. (He himself died a week before the armistice.)

Writing after the anti-war movement of the 1960s, Findley takes the war poets’ antipathy toward authority further when his Robert Ross is raped in a French bathhouse by senior officers from his own side. This portrait of the Great War remains the canonical one, of a war run by leaders who did not care how many young men died, while civilians blithely went about their daily chores, unconcerned, choosing to know but little of the horrors of the trenches.

“You know, their view—what was in the war poets’ books—that wasn’t the conventional take on the war for the first decade after it,” says historian Margaret MacMillan from her office at St. Antony’s College, Oxford. “It just took hold later.” The author of Paris 1919 cautions me against over-reliance on her take, since her academic expertise is in how diplomats, not artists, address the aftermath of a war. However, she remains adamant that the view seen in this poetry and, for that matter, in Findley, is a partial one.

“Most of these writers went to the same schools,” she observes. “There are all manner of other experiences of this war, ones that also matter and are increasingly coming to the fore.”

We find different kinds of characters, and different perspectives, in more recent World War I literature. Where Findley has his Ross’s father arrange to say goodbye to his son next to his private railcar in Montreal, Joseph Boyden has us look at trains from the outside in his first novel, Three Day Road. It tracks two young Oji-Cree men, Elijah Weesageechak and Xavier Bird, trying to come through the slaughter at the front. When Xavier’s aunt leaves the wilds to meet him at a station in northern Ontario, she is fascinated and repulsed by this “iron toboggan…one bright eye shining in the sunlight and the iron nose that sniffs the track.” These machines, and the whole social superstructure that led to the war, are sinister; not one part seems natural to these men.

In their pre-war lives, they suffer through residential schools, famine, and bushfires. Their hunts prepare them well for the battlefield. Only those lucky members of the elite—like Ross and his chums and yes, even Henty—could afford to indulge in nostalgia for a bygone era.

The characters in the Alice Munro story “Carried Away,” published in her 1994 collection, Open Secrets, are also having a lousy time before the war, and its arrival adds excitement—as well as risk and fear—to their lives. In the story, an Ontario boy is provoked by the extraordinary times to write love letters to his small hometown’s librarian, a woman he has never met. He is the son of the gardener for the richest family in town. His letters barely mention the war, and they take a tone as far from Siegfried Sassoon as can be imagined: flat (not grand), matter of fact (not shocked), sometimes even jocular.

It is the beleaguered librarian’s response to the times that I find most interesting: “She felt what everyone else did—a constant fear and misgiving and at the same time this addictive excitement. You could look up from your life of the moment and feel the world crackling beyond the walls.”

For thirty years, I thought Findley had named his protagonist for my great-great-uncle, and the more I learned about the real Robbie Ross the stronger the connection to the fictional protagonist seemed to grow; but when I reached out to the novelist’s surviving partner, William Whitehead, he burst that bubble. The naming, he said, was a coincidence, Wikipedia entries and news reports notwithstanding. “The man is based on an uncle of Tiff’s [Findley’s] and Tiff’s imagination. He wanted a Scottish name for him, hence Ross, and Robert went well with it.”

Yet the coincidence persists as a meaningful one for me. Throughout his life, the real Robert Ross showed a certain moral courage. He never hid who he was. He often spoke inconvenient truths, and he refused to toe the line. On the battlefield, this sort of courage won’t do. Valour often involves the exercise of some discretion—and discipline. If every soldier follows his or her conscience, chaos results.

In the first wave of literature coming out of the war, those with moral courage and a certain delicacy of spirit—in short, artists—are placed under the command of others who require that they violate something important in themselves. Findley’s Ross, after his rape, shoots a superior officer who orders him not to save some frightened horses, and he dies of burns sustained in his efforts to rescue them.

Newer narratives upend some of those old views, just as the war poets upended Henty’s beliefs. In Munro and Boyden, authority figures are seldom monsters. Their soldiers find monsters within as well as without, in the ranks and among the officer class, and their war does not mark the end of something beautiful—a fall from grace, a paradise lost. It’s just an extreme example of how tough and precarious life can be. But the central question in the best World War I literature remains a live one, no matter when it was written: if you are unsure of the justice of your side’s cause, is it still glorious to die for your country?

This appeared in the July/August 2014 issue.