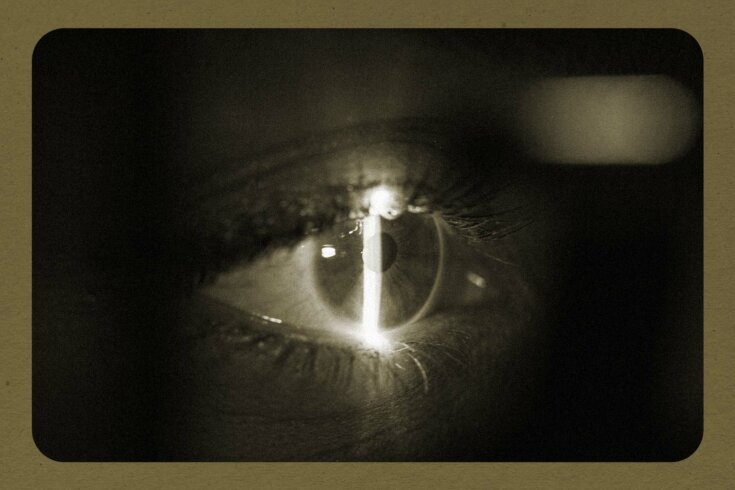

Three distinct personalities, all female, walk into a bar together in Do You Remember Being Born? and emerge with fat paycheques, a collaborative long poem slyly titled “Self-portrait,” and a lot of nagging doubt. Actually, the proverbial bar in Sean Michaels’s dizzying new novel is not a bar but the Mind Studio, an entry-by-key-card-and-retina-scan-only room on an unnamed tech giant’s San Francisco campus. And one of the three personalities, a “2.5-trillion-parameter neural network” named Charlotte, is better described as feminine than female. But the doubt, tucked under a lot of surface-level optimism, is real, instilled in characters and readers alike by the author.

Small wonder Michaels is among the “digital-savvy slate of authors”—indeed, the only one mentioned by name in a Publishers Weekly press release—set to take part in a late-September publishing-industry webinar about AI’s expected impact. Before writing Do You Remember, the Montreal author and critic co-designed Moorebot, a piece of poetry-generation software animated by a literary corpus that includes the collected works of the celebrated American poet Marianne Moore (1887–1972) and an entire anthology of twenty-first-century Canadian poetry. Moorebot, in conjunction with OpenAI’s GPT-3 language model, is an essential co-author in Michaels’s collaborative novel about human–AI poetry collaboration: all the poetry contributed by Charlotte and some of the prose (indicated on the page by grey shading) were generated with its help.

There is far less of the prose than of the poetry, but its effect is more unsettling. When Michaels inserts the shaded words “A swath of solid white—a moonbeam frozen in place, like a streak of static,” he clearly likes the choice and rhythm of the words. What is less clear is whether he intended one insistent effect: it is a lovely image, yes, but was the desire to display it the primary reason why Michaels’s story, which had unfolded in daylight hours, now has an evening scene? Are readers being nudged to look behind the curtain of artistic creativity and to question their own assumptions about what really distinguishes humans from machines?

That’s merely one of numerous subtle chords plucked throughout the novel. Michaels’s main protagonist, seventy-five-year-old poet Marian Ffarmer, is not based on Moore—she is Moore, although the real-life poet never existed in Ffarmer’s world. She wears Moore’s signature tricorn hat and black cape without any reference to a predecessor, and she utters Moore verses as if they were her own. Both poets receive a call from one of their era’s economic titans. In 1955, Moore was asked to suggest inspirational names for a new Ford car and came up with such gems as Utopian Turtletop for the model eventually christened the Edsel, one of the great failures in auto history. The contemporary tech company wants Ffarmer to show the world, via fruitful collaboration, what their Charlotte is capable of.

Ffarmer, far from affluent, doesn’t hesitate to accept the proffered $80,000 commission. She understands—and shares to an uncertain degree—the fears AI has inspired among writers and other creators. As Ffarmer caustically comments, the company wants her collaborative poem as “a memorial for a bygone age, back when only people wrote poems, before my kind had gone the way of lamplighters and travel agents, icemen, video store clerks.” But she desperately wants the money, to give it to her only child, the son she feels she often neglected for her artistic calling. Childbirth, children, and childlessness are as central to the novel as its title signals. Moore was unmarried and childless; so, too (of course), is Charlotte, and she asks Ffarmer, “Do you remember being born?” because she herself is the only one who can answer, “Yes.”

At first, the poet is impressed with Charlotte’s vast “left field”—the store of imagery, ideas, metres, and rhythms provided by the millions of English-language poems fed to her—from which she can instantly craft continuations of Ffarmer’s lines. Then she’s dismissive, as she judges Charlotte’s offerings to be attractive but meaningless word associations. Then she is silenced, upon learning that when her poems were programmed into Charlotte, they came with the instruction, the network says, “to let them have a much more important impact on me than the average”—just one aspect of the tech firm stacking the deck for a successful outcome. The implications shock Ffarmer. Consider the audience, she muses, the pattern-seeking human species and its capacity to take meaning from anything, however hollow. Did she initially warm to Charlotte’s empty contributions because she was seduced by her own voice, she wonders, and was that a career-long tendency she had never noticed? “I wondered how much of what I had published in my life was a deception.”

But despite the company’s various manipulations and Ffarmer’s drive to cooperate, their grand collaboration begins to flail. Enter the third voice: a young, truculent, starving-in-a-garret poet Ffarmer meets by happy accident. For the older poet, Morel Ferarri is the force of nature Ffarmer hopes can soothe her doubts and bind her to her AI mirror. For all Do You Remember Being Born? ’s sweeping consideration of the implications of AI’s arrival on the creative scene, this stunningly compelling novel turns on a far more random arrival: in human affairs, contingency still rules.