At montreal’s expo 67, 2.5 million people lined up—some for as long as seven hours—to see Miracles in Modern Medicine, a nineteen-minute documentary. Before entering the theatre, audience members passed through a dark antechamber, where they encountered such oddities as the “spare parts man” (a Frankensteinian assemblage of prosthetic limbs, glass eyes, and genitalia), as well as light boxes depicting human organs, each glinting like crown jewels. From there, visitors entered a spiral viewing gallery overlooking a hexagonal rotunda, where the film played every half hour on three wall-mounted screens. At the centre of the room, actors performed the onscreen action.

Miracles, which premiered fifty years ago, depicted medical procedures that had never before been widely seen: a six-year-old boy undergoing heart surgery, a woman with Parkinson’s disease having an electrode implanted in her brain, and a thalidomide child learning to use a pair of mechanical arms. More shocking still, it featured a birth scene that included full-frontal nudity. “On April 28, 1967, when the film opened, that sequence would have been the most taboo media image in Western society,” says Steven Palmer, a medical historian at the University of Windsor who, in 2014, rediscovered the film at Library and Archives Canada. At the Expo screenings, some 200 people fainted from shock each day—about 15,000 in total were treated at two St. John Ambulance posts on-site.

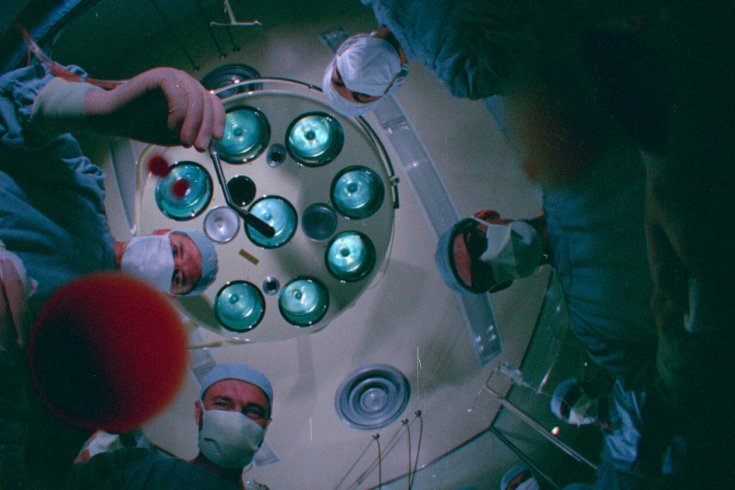

Miracles isn’t just sensational—it’s surreal, with vertiginous camera angles, sharp jump cuts, and loopy montages. Images of machines are superimposed over human bodies. An eerie Hieronymus Bosch painting that depicts medieval trepanation cuts to a sequence about brain surgery. One scene worthy of Stanley Kubrick depicts a heart operation from the vantage point of the organ: masked, scalpel-wielding surgeons lean ominously into the frame. The final shot features a disembodied arm spinning as it sinks into darkness. To comply with the pavilion’s educational mandate, organizers hired narrators to dispassionately explain the procedures in both official languages—the contrast between the audio and visuals only intensifies the uncanniness.

Before Expo, a work such as Miracles would have been considered obscene and relegated to the art-house fringes. At the fair, though, it was a hit. The film is also a missing link: its debut was the moment that the uncensored human body—vulnerable, messy, and abject—found its place in popular culture.

The conventions of medical filmmaking were prudish even by postwar standards. The Motion Picture Production Code, which governed Hollywood, prohibited not just birth sequences but also the use of the word “pregnant.” Even instructional films for would-be mothers typically began with a hospital trip and ended with a baby, skipping the details in between. There was a more candid body of documentaries intended for doctors, nurses, and midwives, but the American College of Surgeons forbade such movies from being shown publicly.

To see true-to-life medical scenes outside of a clinical setting, a viewer would need a membership to Cinema 16, an underground society in New York that screened experimental and explicit documentaries before closing in 1963. Because it was a private members’ club, Cinema 16 wasn’t subject to the censorship laws that governed other theatres, although its participants still took risks. In 1958, Stan Brakhage, whose early works were shown by the club, shot Window Water Baby Moving, which depicted the birth of his first child. When Brakhage sent the film to Kodak for processing, the company threatened to call the police.

It was in this censored world that Miracles was commissioned. As Palmer’s research reveals, the film came about through a strange alliance between the Canadian health care system and the international artistic avant-garde. Carleton Peirce, a prominent Quebec radiologist and the director of health and medical programming at Expo, envisioned a pavilion that would teach visitors about the breakthrough technologies being used in hospitals: nuclear-medicine procedures, kidney dialysis, and a new heart-lung machine. The Medical Care Act, which granted universal coverage to Canadians, was working its way through Parliament—it would pass in 1966—and Peirce was eager to showcase our health care system as part of an international forum.

To curate the Man and His Health pavilion, Peirce recommended Michel Jutras, a medical-school graduate then in his mid-twenties. Jutras was from a prominent Montreal family: his father, Albert, was a distinguished radiologist and arts patron; his brother, Claude, was then one of French Canada’s most beloved filmmakers (although his status has declined posthumously, following accusations of multiple sexual assaults on minors). Jutras envisioned a medical documentary, one that reflected a steely sense of scientific detachment. “I was a young doctor,” he says. “Very few things were taboo to my eyes.”

Organizers hired Peter Harnden, a celebrity American architect who specialized in world fairs, to design the pavilion interiors. They also selected Robert Cordier, a Belgium-born theatre creator who’d collaborated with Salvador Dalí and Allen Ginsberg, to direct the film. Cordier recruited cinematographer John Palmer (no relation to Steven Palmer), one of the cool kids of Andy Warhol’s Factory and a member of the hipster-cinephile community that had grown out of Cinema 16.

In 1966, Jutras took Cordier and John Palmer on a grand tour of Montreal hospitals to shoot their documentary. They brought lighting and camera equipment, which nurses around them scrambled to sterilize. Neither man had a medical background, but they weren’t squeamish about filming surgery. “As a boy, I worked in a slaughterhouse,” Cordier says. “So I was used to seeing bodies cut up.”

During production, Cordier, with his European theatre pedigree, had not considered how sensational the final product would be to mainstream Canadian audiences. “I just hoped that people wouldn’t get up and leave because it was boring,” he says.

Many viewers who were carried from the Miracles screenings on stretchers nevertheless returned for a second go. “There was a sense that you should be able to handle these images because these are the images of modernity,” says Kirsten Ostherr, a Rice University media studies professor. “The film wasn’t just about breaching morals, but also about demonstrating our newfound sophistication.”

After Miracles, graphic depictions of bodies began appearing on TV, first in hospital footage from the Vietnam War, and then in increasingly explicit programs such as M*A*S*H, St. Elsewhere, and ER. It’s unsurprising that Miracles, the first widely viewed film in this canon, was screened in a scientific—or quasi-scientific—setting. Expo gave a scandalous project an air of respectability. Today, cultural programmers who’ve never heard of Miracles still seek to replicate its winning formula: extreme subject matter, which appeals to our morbid curiosity; experimental aesthetics, which flatter our desire for novelty; and scientific high-mindedness, which reassures us that the undertaking is something more than a cheap thrill.

Take, for instance, procedural shows such as House M.D. and CSI, which use computer graphics to dramatize the bodily effects when characters are shot or infected with a disease. “Those images make the storylines seem scientific,” says Ostherr, “but they’re also very sensationalized. Those two functions are fused.” Ostherr also notes that, when hospitals started live-tweeting surgeries in recent years, some centres invariably focused on the most intense subject matter. “The hospitals would claim, vocally, that these initiatives were intended to educate the public,” she says, “but they’d pick a rare procedure like an awake craniotomy, as if that were a common experience that people undergo.”

Even when projects are openly voyeuristic—the Body Worlds touring exhibition, with its flensed human cadavers, or the Medical Realities app, which beams surgeries into virtual-reality headsets—they still have a humanistic impulse: to give us fleeting access to unknown parts of ourselves. We live in our bodies but rarely see much of them. It is mainly through the arts that we can glimpse the messy lives we live underneath our skins.

At Expo, it wasn’t just the visceral imagery, though, that made Miracles compelling. The film took a symbolic stance against medical paternalism. “It was a movement away from the notion that only doctors can witness certain kinds of things,” Ostherr says.

By taking imagery that had been the purview of the MD class and placing it in the public domain, the producers of Miracles imagined a democratized medical culture. Like Expo, the film was aspirational. It relegated primness and bashfulness to the past. The future was for inquisitive types who could handle blood, guts, and nudity.

For many Miracles attendees, no scene was as fascinating as the delivery-room sequence. Steven Palmer describes it as “the iconic experience of Expo.” The fleshy, uncomfortable scene captured an experience that was—or would be—pivotal in many viewers’ lives, but that few had ever witnessed on screen. Rather than patronizing the public, it validated their interest and gave them permission to be curious about themselves. For Palmer, the natal metaphor is especially apt: Miracles heralded the moment when a new cultural sensibility came, gasping, into the world.