T he overlapping coffee rings staining the cover of The Bride and the Wolf told Norman Jewison that the screenplay had been making the rounds. Still, something in the material, written by playwright John Patrick Shanley, spoke to him. It was theatrical, snappy, and, like almost all of the director’s strongest work, situated within a specific ethnic and cultural milieu (Italian American, in this case).

He was also slightly desperate.

By 1985, Jewison was already an almost mythic veteran of the film industry. The Toronto native had been in the CBC’s just-completed Jarvis Street studios in 1952 when the first televised image was broadcast in Canada. He shot up the ranks of live television in Toronto and New York before making the leap to Hollywood. In 1968, his In the Heat of the Night beat out three epochal films—The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner—to win Best Picture. In the 1970s, while Hollywood was leaning in to gritty, auteur-driven fare like Mean Streets, Jewison made Jesus Christ Superstar, the first rock opera to be turned into a feature film. As the industry grew increasingly besotted with effects-driven franchises like Star Wars, in the late 1970s, Jewison reinvented himself as a mid-budget prestige filmmaker, the “actor’s director” to whom stars like Sylvester Stallone, Al Pacino, and Goldie Hawn would turn when they wanted to play against type.

Listen to an audio version of this story

For more audio from The Walrus, subscribe to AMI-audio podcasts on iTunes.

At certain moments of his career, Jewison seemed like the consummate Hollywood insider. Yet the director was keenly aware of the limits of his power. He could never initiate his own projects without green lights from studio heads, with whom he often clashed. In 1985, Jewison was heavily invested in remaking The Man Who Could Work Miracles, an H. G. Wells parable about an ordinary shopkeeper granted godlike powers, which he’d loved since seeing it at Toronto’s Beach Theatre in 1937. He’d worked intensively on developing a new script, and Richard Pryor signed on to star. Then came the rejection—first from Columbia Pictures, then from every other studio in town.

Jewison once believed that, after reaching some arbitrary threshold of success, he would be able to call his own shots. Yet here he was at sixty, still hustling, still facing rejection. Those rejections were “very destructive for me at times,” he confided in an unpublished archival interview. “When I become depressed and disillusioned and forsaken and nobody believes in you anymore . . . you take it personally.”

Such was Jewison’s headspace when Shanley’s coffee-stained script appeared at the director’s office. Executives hadn’t seen anything lucrative or prestigious in this talky, low-key romantic comedy. When Jewison read it, however, he saw something they didn’t: he saw Moonstruck.

Moonstruck, released in 1987, has been having a moment, with some calling it the movie of the quarantine. For Vulture, it was the “Morbid Spaghetti Rom-Com We All Need Right Now,” and The New York Times Magazine concurred: “Under lockdown,” editors wrote, the film became “a salve to many.” But Moonstruck’s troubled origin story appears to have been glossed over in these appreciations, culminating with Cher claiming, “We really, really got along. We just loved each other.” But that’s not quite what happened. In fact, Moonstruck’s success was a triumph over circumstance, which might make it even more of a pandemic touchstone than fans realize.

The conflict-ridden production was, in some ways, rooted in the plot itself. Moonstruck is the story of Loretta Castorini, a thirtysomething Italian American widow who agrees to marry Johnny Cammareri, an overgrown mama’s boy who appeals to her common sense. Then she meets his brother, Ronny, a wolfish, sensitive brute who appeals to her hotter regions. The script makes room for a colourful ensemble of supporting characters: Loretta’s mother, Rose; her philandering father, Cosmo; her dog-obsessed grandfather; and an old goat of a New York University professor who is continually having drinks thrown in his face at the local Italian eatery. But the film belongs to Loretta and her inner conflict between heart and mind.

The studio had plenty of ideas about who should star, including Liza Minnelli, Rosanna Arquette, Demi Moore, and Barbra Streisand. Jewison hadn’t seriously considered anyone but Cher for the role. She had a gritty, streetwise quality that Jewison associated with his no-nonsense protagonist.

Cher’s career had foundered in the late ’70s until a turn in Robert Altman’s Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, in 1982, earned her a Golden Globe nomination and revived her fortunes as an actor. Even in 1986, while Cher was getting choice roles in Hollywood films, questions lingered about her star power in the medium, partly because nobody knew what “star power” really was.

For some industry executives, there were three bankable female movie stars: Jane Fonda, Sally Field, and Meryl Streep. “There is no clear evidence that Cher has pull,” a 1987 story in The New York Times Magazine noted, and “some evidence that she doesn’t.” Surveys conducted by the private firm Marketing Evaluations had found that Cher was well known but not well liked. Her “Q score,” a supposedly objective measure of brand appeal, was lower than the mean for actresses. “She’s never been as popular as she was when she was on television in 1974,” Steven Levitt, the company’s president, said of Cher. “My prediction, based on the data we have, is that people are not going to go out of their way to see a movie she’s in.” Had Jewison known about this research, it’s unlikely that he would have cared. In his mind, Cher was Loretta Castorini.

Jewison was less committed when it came to the part of Ronny Cammareri. It seemed that almost every A-list actor in Hollywood, from Tom Cruise to Bill Murray, was considered for the role of Loretta’s mercurial, one-handed love interest. Jewison scribbled “needs style” and “too young” next to Ray Liotta’s name after his audition—the actor was ten years older than Nicolas Cage, who eventually won the role. Ultimately, it was Cher who pushed for the unlikely choice of “Nicky.” Cage was just twenty-three years old (seventeen years younger than his co-star) and missing two front teeth, which the method actor had removed for his role in Birdy (1984). “He’s not all that great looking,” a Cosmopolitan writer claimed at the time. “Rather, it’s his pouty, hangdog eyes, a look of vulnerability that’s mindful of a lazy morning in bed . . . a brooding look that says, ‘Baby, I can be very dangerous.’”

“Nicolas did have a darker interpretation of Ronny than I did,” Jewison told a reporter in 1988, “but we both agreed that a poetic quality was central to the character. When Ronny is first introduced in the film, he’s in a basement slaving over hot ovens, and he almost has the quality of a young Lord Byron.”

By all accounts, Cage, who was almost entirely nocturnal, brought a punk edge to the ensemble. He patterned his character’s melodramatic gestures on German Expressionist cinema and cited Fritz Lang’s 1927 sci-fi classic Metropolis as a specific inspiration. Cage also owned two sharks, an exotic insect collection, and a jewel-encrusted tortoise. “I’ve always been fascinated by marine biology. I don’t know why. It’s sort of like my bible,” Cage told Playgirl. “I have a picture of a fish in my wallet that is just going to knock your socks off.”

Cage was not the only colourful member of the cast. Feodor Chaliapin Jr., who played Cher’s grandfather (he ad-libbed interactions with his five dogs throughout the film), had great difficulty hearing the other actors. Jewison recalls in the Moonstruck DVD that he got his cues by watching the lips of the actor with the lines ahead of his: when they stopped talking, he’d start. Before casting Chaliapin, Jewison phoned his old friend Sean Connery, who had worked with Chaliapin in The Name of the Rose. “Norman,” Connery told him, “he canna see, he canna hear, and he’ll steal every bloody scene in the film.”

For many viewers, however, Moonstruck’s real star was the screenplay. It was at once ethnically specific and universal—a cornball fairy tale that was also knowing and worldly and wise. Consider the crucial forty-five-second sequence filmed in the cloakroom of the Metropolitan Opera House. Ronny has convinced Loretta to accompany him to Puccini’s La Bohème, an occasion for her Pygmalion-like transformation into what one critic at the time described as an “elegantly tall woman” with “ebony hair corkscrewed into a cascade of curls, her lips the colour of sin on a Saturday night.” But Loretta—still engaged to Ronny’s brother Johnny, played by Danny Aiello—spies her father with his mistress. She confronts him.

Loretta: Pop? Pop, what are you doing here?

Cosmo: What’d you do to your hair?

Loretta: I had it done.

Cosmo: What are you doing here?

Loretta: What are you doing here?

Cosmo: Who’s that guy? You’re engaged!

Loretta: And you’re married!

Cosmo: You’re my daughter, I won’t have you act like a puttana.

Loretta: And you’re my father.

Cosmo: All right. I didn’t see you here.

Loretta: I don’t know if I saw you here or what.

The dialogue crackles with the rapid-fire, thrust-and-parry wordplay we associate with classic screwball comedies. The language also feels authentic to the characters. Trying to pry Loretta away from his brother, Ronny accosts her: “You waited for the right man the first time, why didn’t you wait for the right man again?” “He didn’t come!” she fires back. “I’m here!” “You’re late!” The presiding mood is simultaneously whacked-out and operatic—“rose-tinted black comedy,” in film critic Pauline Kael’s words, a “giddy homage to our desire for grand passion.”

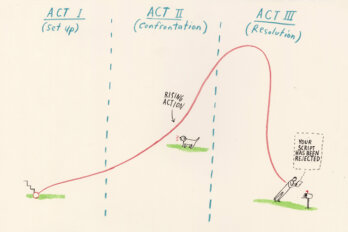

Where the typical three-act Hollywood screenplay scaffolds scenes according to a carefully controlled schema of narrative beats, Moonstruck luxuriated in long, character-building scenes that seemed superfluous from a plot perspective. Take the five-minute restaurant scene in which Loretta’s mother, Rose, played by Olympia Dukakis (who died in May), spontaneously has dinner with John Mahoney’s skirt-chasing professor. Mahoney confesses feeling like a “washed-up old gasbag” while Dukakis offers her theory that men pursue women “because they’re afraid of death.” In an unpublished interview he gave after the film’s release, the late screenwriter William Goldman said, “It’s a glorious scene with two superb actors, but you could cut the whole scene, and nobody would say, ‘What about the restaurant scene?’” For Goldman, Moonstruck was the rare example of a successful screenplay that flaunted the rules of narrative efficiency.

“If it hadn’t worked,” he added, “it would have been so awful, you would have been writhing in your seat, saying, ‘What is this shit?’ But the fact is, it does work, and that’s very audacious—a wonderful piece of work.”

At the time, that success was hard to anticipate. Nothing on set came easy. It started with a frantic schedule that had been compressed to accommodate Cher. After two and a half weeks in New York, Moonstruck moved north—to a converted IBM factory in Scarborough. Further locations included Markham Theatre, Toronto’s Keg Mansion, and Little Trinity Church Park. Then, in a case of life mirroring art, the cast of Moonstruck ended up replicating much of the love-hate dynamic between their characters. “We are all together in a very intense, close relationship,” Jewison said. The sexual frisson between Cage’s and Cher’s characters stemmed at least partly from an ambivalence in their off-screen relationship. “I don’t know if Nicky will ever be a huge mainstream actor,” Cher told Newsweek in 1987. “He takes unbelievable chances, and personally, I think he’s crazy—sometimes he’s a blast on set, other days I’d get real peeved at him.” If anything, Cage was even less effusive about working with the singer he’d loved as a ten-year-old. “I do think she needs a good director,” Cage said of Cher in the same issue of Newsweek. “Otherwise, she’s in trouble.”

Cher sometimes resisted direction, insisting that she knew the character best. “There were certain things that Norman had a lot of trouble getting from her,” recalled co-star Julie Bovasso in an unpublished interview she recorded alongside Dukakis. Cher could be stubborn. One day, after an early-morning call and a number of lacklustre takes, Jewison kept the cast and crew working until past noon. “It was about 1:30,” Jewison told a reporter in 1987, “and I told her something authoritative like, ‘We’ll break when we get it right.’ And Cher turned to everyone else and said, loud, so that they all heard, ‘Did I just hear that? You’re not going to let us have lunch?’” She threatened to report him to the actors guild.

Dukakis felt that Cher’s difficulty had to be understood within the context of her long career. Cher had been toughened by a decades-long stint in show business that had begun with singing backup vocals for Phil Spector on “Be My Baby” and serving as Sonny Bono’s housekeeper at the age of sixteen. “I think she’s been through so much, and she’s been very aware of people controlling her, so that she’s really on guard,” Dukakis said. “I think that’s what working in this business taught her.” Dukakis thought that those close to Cher had told her not to do the film at all.

Moonstruck didn’t feel like a triumph to those who were acting in it. “We were all stupid and didn’t understand what Norman Jewison was really doing,” remembered Dukakis in a 2015 interview. “One day, we were sitting around talking,” she said, “and somebody asked Cher what she thought was going to happen, and she gave the thumbs-down. Nobody really expected too much out of it.”

According to multiple accounts, pent-up tension among the cast finally erupted when filming the climactic scene, in which each character congregates around the Castorini kitchen table for a final reckoning. Everything is wrapped up in the span of a few minutes: Rose confronts Cosmo over his infidelity, Johnny arrives back from Italy, and Loretta confesses her love for Ronny. It was a complicated sequence, and flubbed cues resulted in many failed takes. Actors started telling one another off; at one point, Danny Aiello, Loretta’s fiancé, clutched his testicles and bellowed at Cage, “You gotta give it to me from here!”

Jewison cleared the set to speak only with the actors. He vented his frank exasperation: normally, when he asks actors to try the scene a certain way, they listen. But this pigheaded group had stopped taking direction. He urged them to pull it together and get the film across the finish line, but they launched right into another volley of failed takes. Cage became so consumed with rage, Jewison told a reporter in 2011, that he hurled a chair at another actor.

Finally, Feodor Chaliapin Jr. rose to be heard. “Calma, calma, calma,” he implored. He explained that they were working in the tradition of Feydeau farce, “and in a Feydeau farce, we pull everything together in the last scene.” Chaliapin’s castmates may have been baffled by his reference to nineteenth-century French playwright Georges Feydeau, but the elderly actor’s intervention somehow deescalated the situation.

“We did it again,” Jewison remembers, “and everything fell into place.”

Moonstruck was about the deranging quality of romantic love and one family’s ultimate capacity to contain that wild energy. Feminist critics like Marcia Pally decried what they perceived as the film’s conservative sexual politics: a traditional (puritanical, for some) attitude toward sex also prevailed behind the scenes. In interviews, Cher often displayed an old-fashioned attitude toward romance. “I am monogamous,” she said at the time. “I have relationships, not lovers.” Cher even insisted on wearing a bodysuit during the film’s (decorous) sex scene. Still, much of the film’s manic force comes from submission to the whims of unbridled, irrepressible passion. Jewison revels in Cage’s soaring monologue on the street outside his apartment: “We are not here to make things perfect,” he yells at Loretta. “We are here to ruin ourselves and break our hearts and love the wrong people and die! . . . Now get in my bed!”

Some directors (Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson) never let you forget that you are in the presence of an auteur. Jewison was certainly capable of flashy directorial moves that drew attention to his own creative prowess: the sweeping, magisterial shots of Jesus wailing atop an Israeli cliffside in Jesus Christ Superstar, for instance. The Thomas Crown Affair was so full of directorial flourishes that one critic described the film as “essentially the story of a director directing.” In Moonstruck, by contrast, Jewison largely avoids drawing the viewer’s attention to the hands behind the camera. Here, the maestro devotes his own immense gifts to showcasing the talents of others.

Norman Jewison’s own desires infuse Moonstruck, a film that embraces the mess and entanglements of love, sex, death, wine, music, and food.

This was borne out during the 1988 Academy Awards, when Moonstruck was up for six Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. From his lower-bowl seat in the Shrine Auditorium, Jewison saw Dukakis win Best Supporting Actress. He saw John Patrick Shanley collect his original screenwriting Oscar. (Shanley thanked “everybody who ever punched or kissed me” and “the multimedia princess Cher.”) He saw Cher, dressed in a sheer Bob Mackie negligee bodice, trip on her way up the stairs (blurting “Shit!”) after winning Best Actress. Cher thanked “my hairdresser” and “the lady who taught me how to speak in this Brooklyn accent,” but not Jewison. He saw Robin Williams present the award for Best Director—he’d removed his glasses, just in case, only to hear the rousing ovation Bernardo Bertolucci received for his achievement in The Last Emperor.

The Best Director loss was no doubt lacerating. But, for Jewison, after so many years struggling to balance commercial and artistic imperatives, Moonstruck was an immense personal validation. The wins for Cher and Dukakis further solidified Jewison’s reputation as the preeminent actor’s director; just as importantly, the film was a box-office smash, taking in over $80 million against a budget of $15 million. Moonstruck had stunned the industry to become one of the highest-earning films of the year, outgrossing blockbuster fare like Lethal Weapon and The Untouchables.

Jewison’s presence, especially his cinematic deep yearning, was everywhere in Moonstruck. He wanted to do everything. He directed twenty-four feature films and not one sequel. He frustrated critics who couldn’t find a through line connecting his pictures. The director’s own boundless desires infuse every frame of Moonstruck, a film that embraces the mess and entanglements of love, sex, death, wine, music, and food. It was Jewison’s most sensuous film: eggs and Italian peppers sizzling in the frying pan, strains of Puccini swelling over the soundtrack, the fizz of a sugar cube dropped into a flute of champagne. It was Cher in a black coat against the Manhattan skyline, kicking a tin can down the middle of the street in high heels, a dreamy look on her face. Moonstruck was drunk with life.

Adapted from Norman Jewison: A Director’s Life. Copyright © Ira Wells, 2021. Reprinted by permission of Sutherland House Books.