It’s 1:30 a.m., less than twenty-four hours after the numbness in his limbs began, and Tarek Fatah is being wheeled into an operating room at St. Michael’s Hospital, in downtown Toronto. An anesthesiologist comes in. She looks Arabic, so he asks her what’s happening in Egypt, because President Hosni Mubarak has just stepped down. “I’m Iraqi,” she says. She tries several times to get an intravenous line into his arm. Blood is spurting out. She apologizes. “Coming from an Iraqi, bloodletting should be the least of your problems,” he says for a laugh. She looks offended. He continues: “Hey, for 1,000 years, you guys killed the clans of the Prophet, for crying out loud.” They’re both laughing when a doctor walks in wearing goggles and a headlamp. He’s part of the team that will remove the cancerous tumour discovered yesterday growing on Fatah’s upper spine, and he bends over and looks at his patient’s face. “What the Fatah have you done to yourself? ” This is what happens when doctors listen to talk radio.

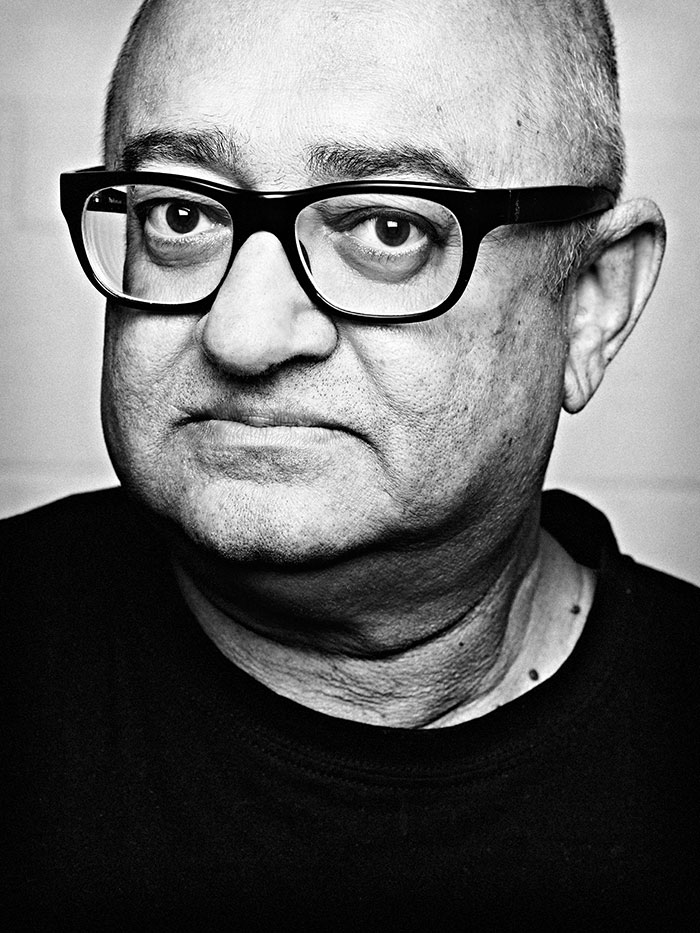

“What the Fatah? ” has become the calling card for the Pakistani-Canadian author and jihadi hunter. He coined the phrase on Toronto’s popular nightly radio program Friendly Fire, where, from August until he got sick in February, he was the irreverent sidekick to Ryan Doyle, the show’s conservative, American-born host. But even if you don’t tune in, Tarek Fatah is hard to avoid. Since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon ten years ago, the sixty-one-year-old has become the face of progressive Islam—safe Islam—in Canada. He regularly appears on TVO’s The Agenda with Steve Paikin and CBC Radio and TV, and in the pages of the National Post and other dailies to denounce the creep into Canada of Islamism, the belief, held by extremist leaders in the Middle East and their minority followers around the world, that Islam is not just a religious path but an expansionist political ideology. Maclean’s once named Fatah one of Canada’s fifty best known and most respected personalities, and his first book, 2008’s Chasing a Mirage: The Tragic Illusion of an Islamic State, has garnered international attention. Saturday Night Live alumnus Dennis Miller, who has a syndicated radio show, interviewed Fatah a couple of times. “You are a piece of work, Tarek,” he told his guest last November. “It’s good to talk to cats like Tarek, because every time I see footage of somebody burning an effigy or going crazy, I always think, okay, let me talk to the cool Muslims.”

Those cats who don’t get interviewed by American celebrities use other words to describe Fatah: “egomaniac,” “pariah,” “fearmonger.” They say he feeds the ignorant a diet of bogus exaggerations and tenuous connections that fortify mainstream distrust of Muslims and conveniently perpetuate his status as a media maven. And then there are the outright haters who accuse him of apostasy. When he got sick, they rejoiced, calling it divine punishment. “T-Fat has cancer, and I’m loving it,” wrote a particularly malicious blogger. A Muslim Somali teenager even made an “open threat” to Fatah on Twitter while he was still in hospital, saying, “I know where you live and where your office is.” Toronto police officers who interviewed her found no evidence that a threat had been made. Outraged at the lack of charges, Fatah wrote in the National Post that it wasn’t the first time the Toronto Police Service had chosen to promote “an image of diversity and outreach” over protecting liberal Muslims against potential violence.

Even when faced with mortality, he doesn’t pull any punches, but nor does anyone else. The public debate among the country’s large and multifarious Muslim population over how to establish a normal, post 9/11 co-existence with secular, mainstream Canada—if it happens at all—is often sullied by fear and inaccuracy. With all the trash talk, it’s tough for outsiders to know who’s right. But maybe that’s beside the point, because away from the headlines something else is happening: a real conversation.

The first time I saw Fatah speak in public was at Ottawa’s Beth Shalom synagogue in January, a month before his hospitalization. Fans waiting outside the sanctuary carried copies of his award-winning second book, The Jew Is Not My Enemy, for him to sign. “He’s a voice of reason,” said congregant Shirley Geller. “We need more people like him.” Shortly before 7 p.m., Fatah appeared through a back door, dressed in his usual suit jacket and beige chinos, looking like a brown Henry Kissinger in dark, square-framed glasses. He delivered a rousing speech to the 200 or so attendees, mostly Jews, then answered questions for an hour, inserting comic relief like a pro between unsettling subjects—Palestine, for instance, a topic he touched on often. “If you are a Jew and you don’t support the Palestinian state, you don’t have a leg to stand on. That is your cross to bear,” he said, a smile creeping across his lips. “I don’t know—can Jews carry a cross? ” The talk ended with a standing ovation.

When we meet for coffee the next morning, he complains about his sore back, attributing the pain to a bulky sleep apnea machine he lugs around when travelling. That was before he knew about the cancer. He gets a coffee refill and is quickly distracted by his favourite subject: the politics of extremism, in this case as it refers both to Jews who deny the rights of Palestinians and to Muslims who want to destroy Israel. It’s ridiculous, he says; you have to warn people about the results of religious fanaticism. Because it comes from a Muslim source, his warning resonates with those already suspicious of the Muslim Other. But Fatah also wants to deliver that message to his own people. In a few weeks, he is scheduled to debate the merits of secular Islam with Sheharyar Shaikh, a conservative imam from Scarborough’s North American Muslim Foundation (NAMF) and its affiliated mosque—the result of an open challenge Fatah issued on The Agenda last November. Toward the end of our meeting, his iPhone chimes its Big Ben ring tone. After a clipped conversation, he hangs up. “That was the Ontario Provincial Police,” he says, dumbfounded. They’re warning him not to attend the debate because it might not be safe. He tries to shrug it off. “I can’t back out,” he says. “They would use that to say, ‘We scared him.’ They can’t get that from me.”

As my mother used to say, attitude doesn’t come from a hole in the ground. Tarek Subhan Fatah was born on November 20, 1949, which he likes to point out was twenty-four years to the day after Robert Kennedy’s birth. More importantly, it was two years after the partition of India and the birth of Pakistan, a complicated and bloody untangling of peoples and cultures. Raised in a liberal Sunni home where the family regularly read the Koran, Tarek (Arabic for “he who pounds on the door”) and his siblings initially enjoyed comfort in a sprawling Karachi mansion, thanks to a fortune inherited from Fatah’s Punjabi paternal grandfather, Ahmad, a French officer and later French consul and industrialist. Fatah’s father, Subhan, was a handsome, charming musician and actor. He could sing like Bing Crosby one minute and recite Urdu poetry the next, all while hosting Bollywood actors at the family estate. He could also drink and gamble to excess: by the time Fatah was eight, Subhan had squandered the inheritance and rendered the family penniless, a reversal of fortune from which Fatah’s mother, Jamila, never recovered.

Fatah went through grade school as a threadbare, myopic boy who taped razor blades to his desk and flicked them with his finger to aggravate the teacher. Twang, twang, twang. Despite the class clowning, he was actually a bright kid and eventually won a scholarship to study biochemisty at the University of Karachi. It was the ’60s, and university was about much more than books, so he lingered there for nearly a decade, taking classes part time while agitating for social justice through a popular Marxist student movement. A Shia classmate named Nargis Tapal saw him speak at a rally and was smitten. They were married four years later and now have two daughters, whom they wryly describe as “Su-shi,” for half Sunni, half Shia. “I was lucky I met her,” Fatah says. “I would go days without eating regular meals. She saved me.” Tapal’s account is a little different. “I would have been a lake: calm, quiet,” she says. “With him, I am the sea, with waves crashing this way and that. On the sea, there is always a roar. That’s my life with him: a constant roar.”

In 1970, while still taking the odd university course, Fatah landed a job at the upstart Sun in Karachi and, later, with Pakistan Television Corporation. He was taught, by some of the best reporters of the day, to speak the truth and be fearless of repercussions—not easy in Pakistan. “He never joined a bandwagon,” says long-time friend Najmul Hasan, a former correspondent with Pakistan Press International who now lives in Etobicoke. “He didn’t care if people didn’t like him.” And some of them didn’t, including high-ranking government officials and the police. “Had we stayed in Pakistan, we would have long ago buried him. In Pakistan, they don’t tolerate people like him, but this is Canada. He can speak his mind.”

By the time Fatah fled his increasingly militarized homeland in 1978, he’d lived through two wars, two coups, and two incarcerations for anti-government activities. “Life is so complicated in our countries,” Tapal says, and by that she means public and private life; for example, Fatah’s family scorned their marriage because she was Shia. “People like you who have not lived there, it’s hard for you to understand.” That’s also true of other countries, such as Iran and Afghanistan, from which an increasing number of new Canadians are arriving. Aside from the FLQ crisis, perhaps, big, dull Canada has always enjoyed relative peace and stability, and Fatah, like many local Muslims who fled persecution or repression, wants it to stay that way.

But if he knows what it’s like to live in fear, Fatah also knows what it’s like to nearly die of boredom. After working as an advertising executive in Saudi Arabia for ten years, he decided he couldn’t raise his daughters in an Islamic country, so he moved to Canada and settled in Ajax, a bedroom community forty kilometres east of Toronto. “What a sad place. It was almost like a prison,” he says, sighing repeatedly in front of the Coffee Time doughnut shop at Clover Ridge Plaza in “old Ajax,” south of Highway 401, where he and Tapal ran a Sketchley dry cleaners. A man exiting the doughnut shop calls out, “Tarek Fatah! I love your show!” Fatah smiles and waves. Radio celebrity is worlds away from his early experience here, surrounded by a United Nations of lonely new Canadians whose only interactions involved swearing at each other in multiple languages while learning to drive in winter.

Fortified with caffeine, we head to his old, grey brick house on Rotherglen Road in Westney Heights, a name he pronounces with a British accent, rolling his eyes. “Suburban dead areas like this take your human spirit and turn it into a property-owning unit. There is no sense of letting down your guard here. You have to fake your existence, from your orgasm to your house. You have to drink beer in the backyard, never the front. So many families I brought to Ajax—they’ve never forgiven me.” But he refused to get stuck. With his wife running the business, he took computer programming courses at George Brown College in Toronto and did some technical writing. Thrilled that he could be a socialist and not get arrested, he also joined the provincial New Democratic Party and ran as a candidate for Scarborough North in the 1995 election. He lost. He and Tapal sold the dry cleaners soon afterward, and he took a staff job with then NDP leader Bob Rae. Meanwhile, he started hosting CTS Television’s Muslim Chronicle, a forum for moderate leaders and scholars to debate issues around Islam.

Then in 2001, four hijacked planes crashed in the US, claiming nearly 3,000 lives, and everything changed for Canadian Muslims. Suddenly, a diverse, multilingual, and largely innocuous community was seen as monolithic and threatening. Racial profiling by police and immigration officials, secret detentions, and deportations drew comparisons to the treatment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War. In this context, a crop of leaders materialized to speak for Muslims, but they were sharply divided between conservative imams who defended Islam, and progressives such as Fatah, who founded the Muslim Canadian Congress (MCC) that December as a modern, secular alternative to the jihadi caricature circulating in the media.

While the fear and frenzy of 9/11 provided the impetus for a radical split, Islam is uniquely designed to allow for this. Unlike Judaism and Christianity, two older, related religions, Islam has no intermediary between the self and God, and therefore no universally accepted religious hierarchy. An imam is someone who can lead prayers, but you don’t need an imam, or even a mosque, to pray. This democratic structure is ideally suited for discourse—or a dogfight. And it seems the Prophet Muhammad feared for the latter. Days before he died, he reportedly took a walk through a cemetery on the outskirts of Medina to pray for the dead. “Happy are you,” he told them, “for you are much better off than men here. Dissensions have come like waves of darkness, one after another, the last being worse than the first.”

On the night of the Scarborough debate between Fatah and Imam Shaikh, a cop stops me as I turn into the parking lot of the warehouse-like Islamic community centre, and I think, wow, they’re actually checking vehicles for suspicious people, but no, they’re just directing traffic. The smell of blood has drawn such a crowd that the lot is full. The officer suggests I park at the strip mall next door. At the mosque’s side entrance, women in hijabs direct me to the right while the men go left, but once we’re inside the main hall’s vast interior NAMF executive director Farooq Khan announces that traditional gender segregation doesn’t apply tonight; men and women can sit where they like. Some mix. Most don’t.

A table and three chairs have been arranged on a riser at the front of the room, flanked by two large multimedia screens. Standing with a few colleagues at stage right is Imam Shaikh, a bearded, thirty-seven-year-old University of Toronto graduate student in sociology and political science, who’s dressed like a banker in a black suit. He is polite and devout, a perfect foil for Fatah, but the two share a similar intensity. All voices are welcome in the house of Islam, Shaikh told me weeks later, but it sounded like lip service. He sees no need for reform; quite the opposite. Muslims should have the option to send their children to Islamic schools, he says, and to return to the ancient texts for guidance on what he calls the non-negotiable aspects of Sunni Islam, such as submission, heterosexuality, and sharia law. Without prompting, he tells me that two members of the Toronto 18 homegrown terror cell had frequented his mosque, including Steven Chand, who was found guilty of participating in a terrorist cell and counselling the commission of fraud for a terrorist group. “I knew the guy. He was a fruitcake,” Shaikh says, “a convert who came from a very delinquent family situation.”

Tonight’s crowd has swelled to about 600. They are mostly Muslim, young and old, brown and white. Women concealed under layers of folded fabric catch my eye and smile warmly; teenage girls in two-tone hipster hijabs and tunics covering their denim-sheathed hips mind their younger siblings or thumb their cellphones. Friends greet each other in Arabic, French, and English, settle in their seats, and check their watches. The room simmers with anticipation.

Shortly after six, Farooq Khan steps to the microphone: he has good news and bad. The crowd moans. The bad news is that Tarek Fatah is a no-show. There are gasps, and a few shouts of “Allahu Akbar!” (God Is Great). The good news is that Imam Shaikh will still deliver his talk. “My heart goes out to each and every one of you, regardless of what you believe,” Khan says. Some grab their coats and leave in disgust, but most remain seated. “You will see tonight,” he adds, with barely concealed sanctimony, “that there is a new brand of leadership that is not afraid, that is confident, that is honest.”

I, for one, am not surprised at this turn of events. Fatah and I spent most of the day together, first in Ajax and then at the skylit townhouse he and Tapal bought in 2002 in Cabbagetown, a gentrified and enviable Toronto enclave just east of downtown. I watched him grow increasingly distracted as the hours passed, his iPhone fixed to his left palm for calls, text messages, emails. By the time we parted, around 3 p.m., it seemed clear he would not debate Shaikh. He had his reasons. The provincial and city police had warned him that they could not protect him. Also, Karen Mock, the mutually agreed upon moderator, had bowed out of the debate two days prior, leading the organizers to appoint an interfaith minister and friend of the mosque in her place. “That was my only stipulation for this debate, that we agree on the moderator,” Fatah told me. He trusted Mock, an educational psychologist and former director of the League for Human Rights at B’nai Brith Canada, as an unbiased public figure. When facing a large and potentially hostile crowd, he said, you need an astute and neutral moderator; otherwise, the discussion can spin out of control.

All reasonable grounds to cancel, I thought. But he didn’t. Instead, over the phone late that afternoon, he confirmed with a mosque volunteer that he was still coming. And he did drive there, with MCC friends Sohail Raza and Salma Siddiqui, but apparently he never got out of the car. Raza and Siddiqui went inside to confront the organizers about the moderator issue. An argument ensued, and security bounced them out. Raza then distributed a press release in the parking lot entitled “An Inquisition Disguised as a Debate Fools No One.” He handed me one as I arrived, shouting, “They are all Taliban, and you can tell them I said so!” (Raza now denies saying this.) The whole charade seemed designed to justify a press release that had already been written.

Nonetheless, Fatah’s absence turns out pretty well for Shaikh, who ultimately claims the high ground as well as the podium. He begins with a tedious, line-by-line rebuke of Fatah’s books, and then a speech on how secular views of female immodesty and homosexuality contradict the wishes of Allah. It might have ended there as a lacklustre sermon, but instead the evening evolves into something extraordinary. For an hour and a half, men and women stand before microphones, some with open Korans, asking Shaikh for evidence of this and that. Sharia law comes up repeatedly. People want to know how the principles of Islamic law would be implemented, who would adjudicate, and how non-Muslims would be treated. One man cautions against literal translations of the Koran, since some passages explain how to hit your wife. Even after the event concludes, a dozen men surround Shaikh to continue the conversation. I am amazed. You’d never see this kind of theological scrutiny in the Catholic churches I prayed in as a kid. And it makes me wonder how much meaningful dialogue I’m missing, thanks to media-perpetuated grudge matches between so-called liberal and conservative Muslim leaders.

Some, such as Shaikh, say the 9/11 attacks triggered an insidious Islamophobia that continues to stereotype a people and demonize a religion. Others, such as Fatah, say they accentuated an existing anti-Western, anti-Israeli sentiment, eventually making it fashionable to disguise terrorism as righteous revolution. But many outside the political sphere suggest that the events shook Canadian Muslims from privileged apathy and prompted a long overdue re-engagement with God.

Facing public scrutiny and forced to profess their allegiance to nation or faith, progressives and conservatives, Muslim nine-to-fivers and homemakers started asking each other questions: Can you be devout without seeming subversive? Can you oppose American interventionism in the Middle East and still be a proud Canadian? What do you believe, and what would you do to protect it? Does wearing a hijab make you a good Muslim? Does opposing sharia law make you a bad one? None of these questions is easily answered, but education and exploration have always been integral to Islam, as Toronto Star editor emeritus Haroon Siddiqui explains in his book Being Muslim. It’s incumbent on those who submit to make informed religious choices. Perhaps Allah wanted it that way. When the Prophet was meditating in a cave near Mecca around the year AD 610 and was summoned by the angel Gabriel to be Allah’s final messenger, the revelation began with one word: “read.”

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the exploration of faith and politics occurred in private—in mosques and hookah coffee shops. Later, the discussion emerged slowly from the closet. Mosques like NAMF and universities organized forums and debates. Toronto began hosting Reviving the Islamic Spirit, an annual conference that draws thousands of Muslims for three days of speeches, workshops, and prayer. While such formal events reaffirm faith and inspire critical thinking, the more important conversations are still unfolding in the community, says Imam Zijad Delic, the Bosnian-born executive director of Ottawa’s modest downtown mosque and Islam Care Centre. He says young people especially are sharing ideas in cafeterias, at family and cultural events, and at Muslim youth camps, trying to improve their communities, strengthen their faith, and integrate into society.

Opinions differ on how to accomplish these goals. Fatah would insist that strengthening Islam in Canada means first purging the ranks of regressive views and then embracing a secular state built on human rights. Others say, ostracize the cranks and focus on the real barriers to progress, such as gender inequality. Sheema Khan, a patent agent whose insightful columns on Islam for the Globe and Mail were compiled in 2009’s Of Hockey and Hijab, says many Muslim women look to their leaders for support and guidance, but they rarely get it. “When Muslim women are beaten and oppressed, these are actions committed in our community,” she says. “The attitudes overseas, that women are not equal to men, people want to maintain them here. That’s not acceptable.” Zijad Delic says most Muslims must overcome a political immaturity that has them ceaselessly blaming others instead of taking responsibility for their own problems—and solutions. “Don’t expect God almighty to make life better for you unless you stand up and make your own changes, until you do the work,” he said during crowded Friday prayers in February. “Home isn’t over there anymore.”

That’s the biggest barrier to community development, Delic adds: most Canadian Muslims only arrived after 1981, and they are divided by history, language, race, class, and sect. A 2007 Environics poll found that 91 percent of Canadian Muslims were foreign born, from more than thirty countries, the top ones being Morocco, Iran, Pakistan, Algeria, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Somalia. Two-thirds are Sunni, with the rest being Shia, or defining themselves as “other” or “no sect.” Partly because of these divisions, Muslim Canadian societies have not evolved, says University of Toronto law professor Mohammad Fadel. They still act like embattled minorities, trying to preserve their idealized culture and religion when they ought to address such urgent contemporary issues as poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, family violence, and youth crime. It’s leaders and mosque establishments, Fadel says, who have remained stagnant as Canada’s Muslim demographic swells in number and complexity. According to one study, the Muslim community will nearly triple by 2030, comprising 6.6 percent of the Canadian population.

It seems clear that Muslim Canadians need leaders committed to progress, now more than ever. While Fatah professes a fierce dedication to Islam, whether he will be able to mobilize the mainstream Muslim community remains to be seen, says Mubin Shaikh, who found himself in the public eye a few years back as a paid RCMP informant in the Toronto 18 case. He’s writing a book about Muslim extremism, and he says that Fatah is justified in warning Canadians about Islamist trends, but that constant warnings without remedies just fuel people’s fears. He adds that Fatah is a maverick who cuts off people and organizations if he suspects a hint of impropriety. Because of Canada’s small, interconnected roster of Muslim aid agencies, cultural groups, religious leaders, filmmakers, writers, and activists, anyone can end up on Fatah’s blacklist—and many do, including a number of the subjects interviewed for this story. That doesn’t advance Muslim causes, Shaikh says. For that, you need an open exchange of ideas, even with your enemies. But Fatah seems more interested in playing truth teller to the mainstream, and with thousands of followers on Twitter and Facebook and access to the country’s most influential media, that role is secure—for now, at least.

Fatah and I have our final face-to-face at St. John’s Rehab Hospital in Toronto, where he is learning to walk again. I need to pin him down on a couple of points, and the timing is dreadful. After surgery and weeks of chemotherapy, radiation, and recovery, he is thirty-five pounds lighter, suffering from nerve damage in his legs, worried about money, and beholden to nurses he accuses of tyranny. He wears helplessness like a full-body rash—insufferably. He asks me to please help him deal with a spill near his laptop, and to open a window to disperse the acrid smell of industrial cleansers.

After a pause in our conversation about his idea for a new book, tentatively titled Some of My Best Friends Are Muslims, I ask him about several of his assertions, for example that Toronto’s Noor Cultural Centre endorses radicals. Noor may not be a poor man’s mosque, as he points out, but it is still a respected organization that hosts film screenings and guest lectures on a wide range of topics, including controversial ones such as Islamophobia and sharia law. “All the people there are Hamas and Hezbollah supporters,” he says dismissively. “It’s fundamentally right-wing, upper-class, bullshitting, fluent English-speaking people to fool white reporters like you.” He is instantly annoyed. “I’m fighting a strong evil force that is out to destroy Western civilization.” Some people think he exaggerates that threat, I say. “I’m not in the PR business,” he shoots back. “Do you think the canary worries about what the miner thinks of him? ” He takes my notepad, scribbles down names of people in Barack Obama’s administration who have been accused of Islamist leanings, and is abruptly transferred to a wheelchair for a physio appointment. In those awkward final moments, he smiles and says, “Why don’t you come back later? ” Then he disappears down the hallway, leaving me with wilting flowers, piles of books, and doubts.

Sometimes I think Tarek Fatah is fighting a complex and thankless battle. At other times, he appears to be Don Quixote, stabbing at enemies that aren’t really there. Maybe he’s just a performer, like his dad. In any case, few could deny his pivotal role in shaping the past decade of Muslim politics in Canada. His frequent and vehement opposition to sharia law, for example, likely helped to convince Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty to eradicate religious tribunals in 2006. Though some say the debate was so steeped in rhetoric that it prevented reasonable discussion, others still call him a hero for it. And even though he skipped the debate with Shaikh, Fatah was the reason all those people showed up. Maybe they came for the spectacle, or just to see, up close, the face of an enemy. Maybe they wanted to learn something. Regardless, they brought their kids and shared opinions for hours. Every community needs a provocateur.

Fatah says he’s fighting a war for truth, but he’s been fighting all his life, against apathy, elitism, dogma, suburbia, obscurity, poverty, mediocrity, and now lymphoma. Which begs the question, when this war against Islamism is over, what the Fatah will he do? I asked him once if he had any heroes. He smiled, pleased with the question, and told me about Khair Bux Marri, with whom he once shared a jail cell. Marri is an octogenarian freedom fighter from Balochistan, a region of Pakistan that has fought for independence, and suffered brutal oppression, for decades. “In my heart, I am Baloch,” Fatah said. So the question about his future is moot. There is always another battle.