He says, slowly, that there is an island in Grand Lake called Glover Island. And Glover is the largest island on the island of Newfoundland. And on Glover there is a pond. And on that pond there is a smaller island. I want, he says, to paddle up Grand Lake and portage over Glover Island. Get to that pond and cross to the island and spend a night. He says there’s only one other island in the world with a lake holding an island, and a pond on that island with an island in that pond, and that place is Sumatra. And if you took a globe and put a finger on Newfoundland and another finger on Sumatra you’d see they’re pretty much on opposite sides of the earth.

Winter’s excerpt is one of my favourite pieces of fiction about Newfoundland. I love the incantatory rhythm and the sense of the island’s isolation and its intricate and absurd relationship with the rest of the world. There’s the poetic complexity of islands within islands, the bracing sense of authority in the voice. Also, the gleeful audacity: there isn’t a scrap of truth in the whole paragraph. But it did make me wonder if there is an island on the other side of the world where someone might be writing something equally as wonderful and might that place be weirdly exotic, as Newfoundland is, and hard to get to and not too tarted up yet. But this place, exactly on the opposite side of the world, were you to put your fingers on the globe, might be warm instead of cold and have beautiful beaches and glorious surf and vineyards and might I go there, I wondered, and investigate and possibly get a tan in the middle of March and see strange animals and smell the mildly intoxicating perfume of the eucalyptus forests, the fuggy fumes released by a hot sun.

I am lying alongside my friend, the Newfoundland filmmaker Barbara Doran, on a beach in Swansea, Tasmania, for three hours, and it is hot. There’s not a scrap of garbage or a building or a living creature, man or beast, for three hours, though there are some deep and menacing claw marks in the sand. Barbara is reading Nicholas Shakespeare’s In Tasmania and the page she’s reading is set on the very beach upon which we are sitting. Shakespeare lives in the neighbourhood.

After a time, Barbara reads aloud to me the infamous story of Alexander Pearce and the escape from the Tasmanian prison of Sarah Island. In 1822, eight convicts escaped together, first stealing a boat to get off the island and then hacking their way through the forest toward Hobart. Gradually, they ran out of food and began to murder and eat each other until there were only two convicts left, Pearce and Greenhill. The two convicts watched each other over a bonfire all night long, waiting for the other to fall asleep so he could be murdered and eaten.

The last survivor was Alexander Pearce, “a pockmarked Irish shoe-thief.” Pearce returned to captivity, exhausted and half-starved, and gave a full account of the escape. At first, authorities thought he was making the story up to cover for the convicts thought to be still at large. But after a second escape attempt, from which Pearce returned voluntarily, authorities found a piece of human flesh in his pocket. Pearce admitted that he had developed a taste for it. One of his fellow convicts had advised him that the upper part of the arm was the best-tasting flesh.

I look out over the starkly beautiful beach, after the story of Pearce and Greenhill, and it strikes me: we are at the very end of the earth.

Despite all the differences between Newfoundland and Tasmania, there are also compelling similarities. The most tragic similarity is that both of the islands’ aboriginal populations were decimated as a result of European settlement. We are also both islands off the coast of a continent; we are both ridiculed by our respective mother countries. Newfoundlanders are lazy and stupid and Tasmanians are inbred, the story goes. The joke is that the Tasmanians are so inbred that they’re born with two heads. In the Salamanca Place market, in Hobart, they sell T-shirts with two necks, just as you can find miniature models of Newfie outhouses with two floors in some joke shops around St. John’s.

Most importantly, both islands have gone through a burst of astonishing literary production in the last twenty years that has caught the attention of the world. Just as Newfoundland author Wayne Johnston put the province on the literary map with his novel The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, so Richard Flanagan made the world aware of the rich cultural heritage of Tasmania with his novel Gould’s Book of Fish.

When I meet with Pete Hay, a Tasmanian poet and the author of Vandiemonian Essays, he talks to me about the importance of Richard Flanagan’s work. “There has been a great deal of repression when it comes to stories and histories here, faked genealogies and changed names to hide convict pasts,” he tells me. “Even the name of the island was changed from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania. But for some reason, Flanagan’s family had no embargo on those stories. Richard Flanagan’s novels, Death of a River Guide and Gould’s Book of Fish, breathed a new openness into the past and people began to search for the truth and feel proud of their stories.”

I have noticed that, after only a few days in Hobart, when I ask for directions in the street, helpful strangers casually volunteer their convict ancestry.

“You have to go to Port Arthur to really understand the convict past and I hope you get a grey, rainy day, because that’s the best way to see it,” Hay says.

Barbara and I drive to Port Arthur, an hour and a half outside Hobart. The road is so windy and narrow it causes my stomach to lurch, and there’s the optical illusion (I hope it’s an optical illusion) when Barbara is driving that at any moment she’s going to cream my side of the car up against the hulking cliffs. We’re driving on the left-hand side of the road. Neither of us, it turns out, really knows our right from our left.

There’s roadkill every mile, wallabies with their stiffened legs sticking up, as if clawing the sky for breath, and other fat furry things with teeth, bigger than dogs, half-flattened and unidentifiable. I figure Barbara and I have about as much chance of making it out of Port Arthur alive as some of the convicts from the 1800s.

Then I find myself standing in a punishment cell. I pull the heavy door closed behind me. The walls are thick sandstone bricks. The air is damp and smells faintly fishy. The darkness isn’t the kind to which the eyes gradually adjust. The blackness is absolute, a form of live burial.

Port Arthur’s Separate Prison, completed in 1852, is modelled on the work of the philosopher and prison reformer Jeremy Bentham. Bentham believed that sensory deprivation, coupled with a rigorous moral and spiritual education, could shape the minds of even the most dangerous, unrepentant criminals. Or as he put it, the prison could function as “a machine for grinding rogues honest.”

Port Arthur is physically isolated in relation to the rest of Tasmania, and in the 1830s, when the convict settlement was established, there were no road links. The settlement was not only self-sufficient but became a major exporter, producing shoes, furniture, barrels, and ships, with its ready population of what was essentially slave labour. Most of the prisoners transported to Tasmania in the 1800s were petty thieves. They had probably stolen a loaf of bread or a few potatoes, but they were repeat offenders. At Port Arthur, compliant prisoners were offered an education and the chance to develop a trade. The more dangerous criminals wore leg irons and were sentenced to hard labour. They worked in felling gangs in Huon Pine forests, gathering lumber for the burgeoning shipbuilding industry.

The hard labour quickly destroyed the men’s bodies and sometimes killed them. The leg irons—I lifted one and it took both hands—dug into the men’s flesh and the resulting open sores became infected in the tropical climate. There was scurvy and rampant respiratory disease. Only the prisoners who refused to submit to the slavery that Port Arthur imposed were sentenced with solitary confinement. They were fed bread and water, and were led to the nearby chapel in calico hoods with slits cut for their eyes. The hoods assured they could see nothing but whatever lay straight ahead.

The chapel is a humble stone building fitted inside with separate wooden cubicles for each convict. The stand-up cubicles, each about the size of a coffin, were constructed so that the prisoner could look only at the lecturing parson in front of him. I stand for a moment inside the cubicle and close the wooden door between my cubicle and the next. There’s a tourist standing in the pulpit taking pictures. The flash bounces in my eyes, temporarily causing a blind spot. Someone has moved into the cubicle next to mine, blocking my exit. I give a little tap, just to let them know I want to get out. Nothing happens.

“Okay, let me out,” I say.

“No,” says the woman on the other side. It takes me a beat to realize it’s Barbara.

Then she says, “Just kidding.”

We take a tour boat around the harbour and circle the Isle of the Dead. The tour guide directs our attention to Point Puer, where child convicts were incarcerated. The guide shows us the bathing spot on the shore where these children were forced to jump into the icy Antarctic waters each day, summer and winter, for a constitutional bath.

Strange business, this convict tourism, I realize—how to take hold of such a grisly past? How to make it palatable to tourists? Upon paying an admission fee for the museum, each tourist is given a playing card that matches up, at the end of the tour, with a real convict. I am given the king of hearts and when I open the wooden slot that shows my convict’s name and particulars I find my own name—Moore. My convict is a William Moore, who was trained, during his incarceration in Port Arthur, as a blacksmith. He was transported from Ireland for stealing a plug of tobacco. It is an eerie coincidence; what are the chances?

Later, at the airport in Launceston, I run into a man who recounts his own convict ancestry with a robust conviviality. When I tell him I am from Newfoundland, he is delighted.

“Your ancestors must be convicts too,” he says. When I say I don’t think so, he looks disgruntled.

“Well,” he says, “I guess your ancestors might have been fishing admirals. There were a very few of those as well.” And he gives his newspaper a little snap and turns away from me.

But the truth is convicts were not transported to Newfoundland. As historian Gerry Bannister explains in The Rule of The Admirals: Laws, Custom and Naval Government in Newfoundland, 1699–1832, there was a pivotal case concerning a group of over one hundred Irish convicts who had arrived in Bay Bulls and Petty Harbour in July 1789. They were starving and sick from the transatlantic voyage and they made their way into St. John’s with plans to burn the city to the ground. The authorities insisted they be sent back to Ireland, and Ireland refused to take them. But the Newfoundland authorities eventually won out, citing a law that stated that Newfoundland was not a British settlement; in fact, settlement in Newfoundland was illegal. Another law clearly stated convicts had to be transported to British settlements.

I had tried to get in touch with Richard Flanagan before I arrived in Tasmania but he was in the throes of completing a new novel and not available for an interview. When I do finally run into him it’s at a private party to which Pete Hay has invited Barbara and me. Hay says Flanagan will be performing. I have an idea what Flanagan looks like because I’ve seen the portrait of him by the Tasmanian painter Geoff Dyer. Dyer had won the Archibald prize, an Australian award for portraiture, a few years before. He’d painted Flanagan with his eyes too close together, as though he were turning into a fish. The fish eyes are a reference to Flanagan’s Gould’s Book of Fish. It turns out Flanagan’s eyes are actually as blue as the flame of a blowtorch and he’s rugged looking, fit, energetic, and very welcoming.

It’s election night in Tasmania and Flanagan is performing stand-up comedy, political satire about the election results as they pour in from around the island. Most of the writers I’ve been talking to are members of the Green Party, which got its start in Tasmania in 1972 when the government was planning to flood Lake Pedder for a hydroelectric project. The gist of the comedy is very local. I’m in the back of the bar and I can’t really see over the crowd—they’re roaring with laughter—and though I’m missing the show, I get to talk to the Tasmanian writer David Owen about sharks. It’s noisy and we have to shout in each other’s ears.

“Sharks are misunderstood!” he yells.

“What’s to misunderstand!? ” I yell back. I’ve already asked, in Melbourne, about the theory that you can just give a shark a good punch in the nose and then make your getaway. I was told to imagine the speed with which they come through the water, and their considerable size.

I think David Owen’s comment about people misunderstanding sharks (those intrepid, cold-blooded, malevolent monsters of the sea, as I have come to think of them) is meant to quell my fears of swimming. But I’m way past my fear of sharks. Snakes are the real danger, I’ve come to realize. Three separate kinds, all poisonous.

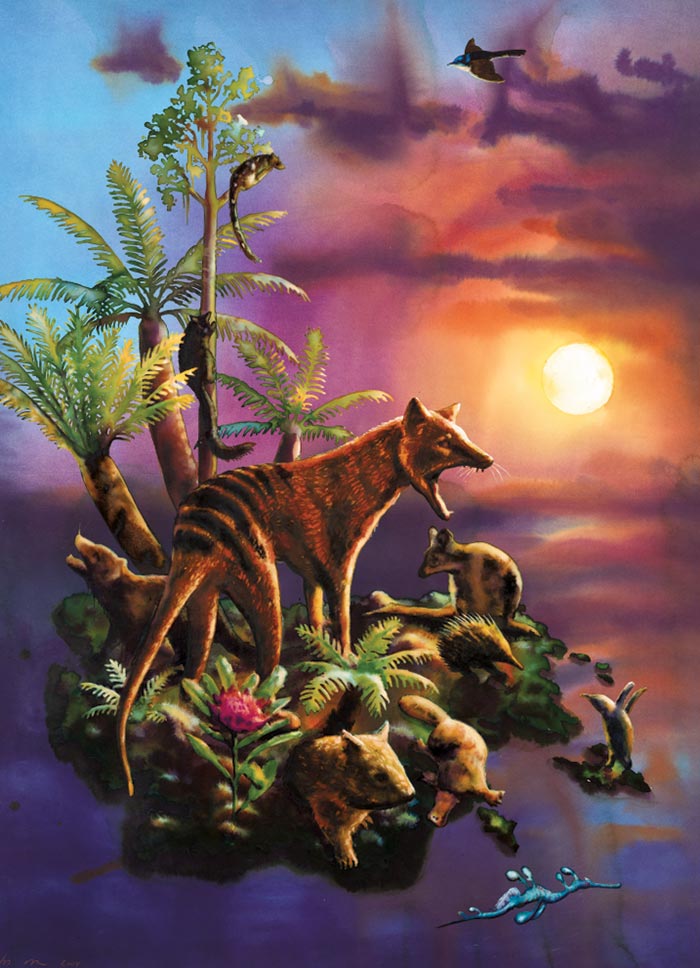

Tasmania is known for its wildlife. As Nicholas Shakespeare says in his memoir, there are areas of rainforest that no human has set foot in for hundreds of years. The famous Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, was a marsupial with a striped back, the jaw of a tiger, a stiff tail like a kangaroo, about the size of a big wolf. There was a bounty put on the tiger’s head in the 1830s, and, although the bounty was rescinded in 1909, the last known Tasmanian tiger died in the Hobart Zoo in 1936. Although there has been no hard evidence that the tigers are still alive, no scat found in at least thirty years, there have been repeated sightings. The tiger has gained a mythic status in Tasmania. It has come to represent the spirit of Tasmania for many people: the exotic, the wild, the untouched frontier.

The Hunter by Julia Leigh is a slim, elegant, and quietly moving novel about a man trying to find the tiger. The novel is being adapted for the screen. I ask Pete Hay what he thinks of it. He draws himself up slightly before he answers.

“What do you think of The Shipping News? ” he asks.

The Shipping News is a controversial novel in Newfoundland. Annie Proulx got it wrong, is the general consensus; she mined the Dictionary of Newfoundland English and stuffed the novel with Newfoundlandisms that somehow don’t come off sounding quite right.

She’s got us all wrong, and not on purpose, as Michael Winter does in his beautiful paragraph. Hay tells me that Leigh’s book also gets things wrong, such as the names of various eucalyptus trees. Leigh is not from Tasmania and Proulx is not from Newfoundland. These writers are guilty of the sort of mistakes that only a local could care about or even notice. And in the context of fiction, is there even such a thing as getting something wrong? The authors’ intent was surely to create a work of art, and both of these works are masterful. So why does it matter?

It matters because we expect literary fiction to be universal and particular at the same time, and accurate in its particularities. Tasmanian and Newfoundland literatures have captured the international imagination, to the extent that they have, partly because they are charting uncharted territory—the specific details of place, voice, cadence, and wit that come from living on islands at the periphery, at the ends of the earth. London, Paris, Rome—these are places that have existed as solid landscapes in our imaginations for centuries. But the imaginary landscapes of Tasmania and Newfoundland are still relatively wild.