In an early scene in 1974’s Murder on the Orient Express, the characters sweep through the Istanbul station toward the storied sleeper. The platform at Toronto’s Union Station isn’t quite as vibrant this early May morning—there’s no sense of being in a teeming bazaar, no provisions being inspected by a chef at the dining car, not one goat—but there’s still an air of anticipation as we embark on the Canadian. The gleaming stainless steel cars and the signature domes hint at the adventure ahead. As an ad for the trip promises, we’re going to “glide through gentle prairie fields, rugged lake country and picturesque towns to the snowy peaks of the majestic Rockies.”

Not on the route through those majestic Rockies is Craigellachie, BC. One of Canada’s origin stories is the driving of the Last Spike there in 1885, symbolizing the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway transcontinental system. In his bestseller The National Dream, popular historian Pierre Berton described this endeavour as “the dawn of a new Canada.” The thing is, use of the tracks that run through Craigellachie was ceded to a luxury excursion operator, Rocky Mountaineer (“Truly Moving Train Journeys”), more than three decades ago. Since then, the Canadian has exclusively taken the arguably less dramatic—and less historic—Edmonton–Jasper route.

It’s hard not to see this as a metaphor.

Declining service is certainly a through line in the Canadian’s story. When it was launched by CP in 1955, it ran each way daily, as did its competitor, Canadian National Railway Company’s Super Continental. Today, Via Rail, the Crown corporation that was incorporated in 1977, is the boss, and there’s just the Canadian, which is down to two trips a week. When the train was introduced, the Toronto–Vancouver journey took three nights; now it’s four. Though the revised schedule offers more hours in the Rockies during daylight if you’re going east to west, the principal reason is that freight trains get priority on the tracks, so a lot of that extra time is spent sitting on sidings.

One aim behind Via’s takeover of the CP and CN passenger services, a money-losing business those companies were eager to get out of, was to stop duplication and reduce the federal subsidy needed to keep the trains running, which totalled $181.1 million in 1976. Of course, in Canada, long-distance trains as a form of intentional transport had been losing passengers since the mid-twentieth century as better roads meant it was easier to drive and flying became more affordable. So the aim wasn’t only to serve people wanting to get from, say, Kenora to Kamloops.

By the point CP introduced the name “The Canadian” in 1955, it was selling “Canada’s first and only stainless steel Scenic Dome streamliner.” (The glassed-in domes are still marvels, their upper-level seats always coveted for their panoramic views.) The tag and the stainless steel rolling stock were retained after the CN (Edmonton–Jasper) route was dropped in favour of the CP (Calgary–Banff) tracks when Via took over. At the time, Frank Roberts, the first Via president, declared, “This country was put together by a band of steel and, by God, it’s going to be held together by a band of steel.”

He was both romantic and right about how the railway was central to the creation of Canada: British Columbia held out for the promise of a rail link before signing on to Confederation in 1871; the role of the transcontinental trains in bringing millions of settlers to the west is well documented.

But today? Is there still a place in Canada for the Canadian?

It’s 2:30 in the morning and I’m doing email as the train sits on the tracks at Hornepayne, Ontario. It’s one of the few places through northern Ontario where there’s cell signal, for reasons that are obvious if you look at a map. It will be another seventeen hours before we get to Winnipeg, travelling through widely dispersed hamlets and villages, vestiges of gold strikes or the fur trade or the timber business. When it gets light, we’ll see melting ice on the lakes and snow patches on the ground—and the constant reminders of the engineering feat this part of the line represents: the hundreds of cuts blasted through the Shield to lay the tracks.

This trip is my eleventh on the Canadian. Here’s my best story: It’s the early ’80s and I’m on my way to Banff. At Chapleau, a scrappy northern Ontario town west of Sudbury, I get off for an overnight visit with friends. The next day we motor across their lake to . . . nowhere, just tracks cutting through the bush. As it approaches, the train slows, then stops. It’s a whistle stop, and the only person getting on is me.

Price was the reason for my first three cross-country back and forths—childhood visits to West Coast relatives. In 1955, when the Canadian was introduced, a return ticket from Toronto to Vancouver on Trans Canada Airways cost $289, while return in a tourist-class lower berth was more than $100 cheaper. (To put that in perspective, $100 in 1955 dollars equals more than $1,000 today.) The difference in price perhaps explains an otherwise opaque CP promo line from the time: “The Luxury of Economy.”

Today, Via’s slogan is the bland “Love the Way,” and a lower berth Toronto-to-Vancouver one way costs about $1,500 before tax in high season, which is six months of the year. Relative luxury compared to coach, but certainly no economy.

Coach, which is about $500 one way in high season, means trying to sleep sitting up. There’s greater legroom than on a typical commercial flight, and the seats recline more, but for all but the most resilient, a multi-day trip is rather like being trapped on an endless red-eye. These days it’s also substantially more expensive than flying, which you can do for around $400, return.

I did a coach trip once. After the first brutal night, during which it seemed as if some passengers were playing basketball in the aisle, my then husband and I stumbled off the train in Sioux Lookout and hit the nearby liquor store for some wine to anaesthetize ourselves that evening. Screw-top options were rare at the time, and what we picked was a bottle of still rosé—barely drinkable, even under the circumstances. On this trip I watch a couple of people from coach sprint not to the liquor store but a nearby grocery—if you’re in economy, you’re not welcome in the dining car.

That’s a clue to the rigid class structure on the Canadian. Coach is a land-based version of steerage: in this section of the train, aside from one or two sixty-two-seat cars, there’s a combination modest cafe and dome car; that’s about it. Then, there are the “Sleeper Plus” options: in ascending order, upper and lower berths, cabins for one or two, and bigger configurations like “drawing rooms.” I can remember, on those long-ago family trips, peeking through open doors at these spaces, which seemed the epitome of opulence compared to our berths. There’s a shower on each Sleeper Plus car, and all these options include meals (prime rib, lake trout . . . ). By contrast, economy choices are described, ominously, as “wholesome and comforting,” code for packets of nuts and microwaved cheeseburgers. Fellow passengers can be even more alarming than the food: a few weeks after my trip, a young relative was travelling economy and there was a stabbing on her car. And as if to underscore their charmless utility, the showerless coach cars are just numbered, while the sleeping cars are named after historic figures like explorers or administrators of the early colonies: Laird Manor, Burton Manor, Chateau Varennes. (I can’t help but imagine that Via is bracing for the day when some of the people for whom the cars are named are called out, à la John A. Macdonald.)

The Lamborghini of accommodation is Prestige: cabins for two that are 50 percent larger than the standard ones, with a mini fridge, an ensuite that includes a shower, and seating that turns into a double bed. Oh, and concierge service. The price would be a start on the down payment for that Lamborghini: $13,500 for two in high season, one way. Bookings for 2024 are already strong.

While the Prestige passengers must eat their meals with the other Sleeper Plus travellers, they have access to a special car at the end of the train, the Glacier Park, that the rest of us can visit only after 4 p.m. Or in the case of the coach passengers, never.

I’m grateful not to be riding in coach but in a two-person cabin—on the Carleton Manor—that Via has comped me; the early-May rack rate for it is close to $5,000. The company has also supplied me with a minder, a senior staff member, personable and knowledgeable about the train service, who is accompanying me on the trip west. I assume she’s there to buff my experience, though I’ve tried to make it clear that I’m not writing a travel piece.

The apparent misunderstanding likely stems from the fact that catering to the high-end tourist trade is part of the Canadian’s purpose. Via notes in its 2021 annual report that the trans-continental train provides “intercity service connecting communities while supporting Canada’s tourism industry,” but the spartan coach conditions are a clue as to which of those two is the priority. Though in fact tourism has been an objective of train travel almost since the Last Spike ceremony—as early as the late 1880s, CP was promoting its service as “The New Highway to the Orient.” A few years later it was exhorting well-heeled Canadians to forgo Europe and experience the train trip: “All our citizens need an idea of the beauty and grandeur of our own Country.”

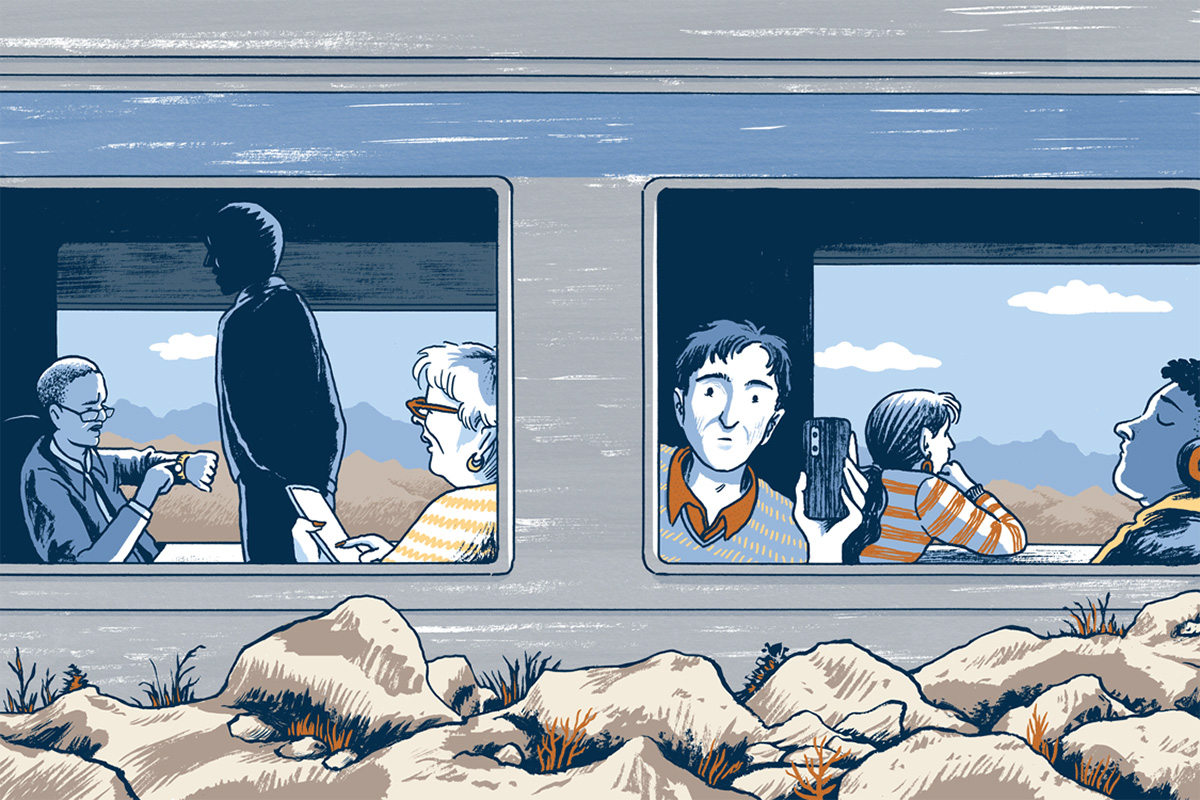

Couldn’t citizens still do with a hit of beauty and grandeur? Likely, but just as a century ago only a slender minority could choose between cruising Canada and a Grand Tour of Europe, today, outside of the economy passengers, many of those travelling are retiree couples who are experiencing what’s been described as “one of the world’s greatest train journeys.” In Sleeper Plus, under-thirties were so rare on my trip that I cornered a few, wondering what had attracted them. One high-spirited fellow described himself as a “sixty-year-old soul in a twenty-year-old’s body.” Two young guys from France were in Canada on work visas. Their reason for taking the trip was basically the same as everyone else’s: to see the country, particularly the mountains. When I checked in several days later, they were having a fine time. But were they surprised at being in such a minority? Non—the price had been a clue as to whom they were going to meet.

What they didn’t say was that, collectively, the Sleeper Plus passengers on this trip were a pretty homogeneous lot. The diversity was at the front of the train—the coach passengers trended younger and less affluent, and were more likely to be people of colour. One reason: the Canadian is the only transport option between many communities for the carless, now that much bus service in rural areas is spotty at best. For a quarter of the coach cohort, who can make up about 35 percent of all passengers, the train is as much the way of getting from one place to another as it was 100 years ago. Expensive, though. One example: the five- to six-hour return trip between Sioux Lookout and Winnipeg involves about $150 and patience, given the twice-a-week schedule.

Meanwhile, in the high season, tourists from the US, Britain, and elsewhere represent a significant proportion of all riders. Essentially, Canadians are underwriting their holidays. Pre-COVID, the per-passenger subsidy for the Canadian was around $650, ballooning to over $1,000 in 2022. That works out to more than $50 million—the 2022 ridership was 51,500, or about the same as the population of North Bay, Ontario. No one seems to have tallied the number of passengers who rode the Canadian in its inaugural year, but the total number of rail passengers in 1955 was 27.2 million, while by 2022 that figure had dropped to 3.3 million. In the same year, ten times as many people flew domestically.

True, it’s not just the Canadian that’s a losing proposition: only 3 percent of Via passenger trips are long distance; almost all the rest are intercity in the Quebec City–Windsor corridor. This service is also underwritten—2022’s total operating loss topped $350 million—but at a substantially lower level: in 2022, the per-passenger subsidy in the corridor was a little under $70, a figure that has likely dropped closer to the pre-pandemic $30 by now. It’s this intercity service that is more comparable to the European model than the transcontinental trains. The reason, of course, is geography. It takes far less time to travel from Paris to Brussels than it does to get from Montreal to Kingston; Amsterdam to Berlin isn’t much longer than Windsor to Toronto. Plus, when it comes to subsidies, it’s only fair to note that many more government dollars go to roads. For example, a couple of years ago, Ontario allocated roughly $3 billion for road and bridge construction and maintenance.

Among Via’s promotional photos there are several that feature a couple of white seniors being served by a broadly smiling Black employee. It’s a tone-deaf image that evokes the shameful decades-long exploitation of Black sleeping car porters. What were the Via PR people thinking? I wonder whether any of them happened to see The Porter, the award-winning 2022 series portraying porters’ harsh working conditions in the 1920s. What about my fellow citizens on the train? Nope. (A Via manager I ask has seen a few episodes and assures me that the Black porters of the past “took great pride in their work.”) How about The Sleeping Car Porter? The rigorously researched novel, the story of a queer Black porter working a punishing Montreal-to-Vancouver shift, was the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize winner. Suzette Mayr’s compelling story is also a history lesson that . . . no one I poll has heard of. The people in Prestige, a group of American college alumnae, have been given a Canadian book by the tour operator. It’s not The Sleeping Car Porter, though, but an Alice Munro collection. I ask a woman carrying the book how she’s enjoying it. Not much, she confesses, adding that she supposes there aren’t that many Canadian writers.

There are other narratives that are elided. The colonist cars, for one. The transcontinental trains were the conduit for the settlers lured to the “empty” prairies (“Special farms on virgin soil”). The purpose-built cars that carried millions west to usurp the lands of First Nations offered bare-bones transport—the seats were unpadded and riders had to supply their own bedding and cook their meals in the tiny galley at the end of the car. There are two extant CP colonist cars in the country; I tour one of them in the railway museum in Squamish, visualizing my maternal great-grandparents, grandmother, and her siblings riding in it as they emigrated from Ontario to infant Alberta in the early-twentieth century. They were welcome there. One CN advertisement promised “the right land for the right man”; a CP promotion made it clear that the right man was a white British citizen.

Two days before I left, Gordon Lightfoot died, which reminded me of another history lesson. In 1967, the CBC had commissioned Lightfoot to write a song to commemorate Canada’s centennial. The result was “The Canadian Railroad Trilogy,” a haunting six-and-a-half-minute ballad about the building of the CPR. The last line—“And many are the dead men too silent to be real”—alludes to the staggering mortality rate for the men who worked on the railroad, particularly among the estimated 17,000 Chinese navvies, who were assigned the most dangerous work, like handling explosives. Lightfoot’s Globe and Mail obit noted how Pierre Berton sometimes joked that “Trilogy” told the story of the railway’s birth as well as his own book The Last Spike. No one I ask knows the song.

Is it unreasonable to think Via should be offering a bit of history on the Canadian—The Canadian!—along with the wine tastings, trivia contests, and inevitable bingo? As the flagship of the corporation, for me, at least, the train represents an almost mythical connection to the country’s formation, a mobile historic site that’s tangible evidence of the inconceivably challenging 4,500-kilometre project that was completed in just four years. (In Toronto, there’s a nineteen-kilometre transit line now in its thirteenth year of construction.)

Between 1954 and 1986, the Park cars had murals of . . . parks—Algonquin, Banff, Riding Mountain—painted by prominent artists of the day, including three Group of Seven members. Today, the most historic reminders on the train are items like old dining-car cutlery and a conductor’s hat that are displayed in modest glass-fronted cabinets in the dome cars.

On day three, we roll into Edmonton at about 9 p.m.; on the outskirts, we’ve seen plumes of smoke that seem awfully close to the tracks. Theoretically, it’s a three-hour stop; however, we’re still sitting there in the morning. Bordered by a chain-link fence topped by barbed wire, the platform has all the charm of a maximum-security institution. Unlike the Winnipeg and Toronto grand beaux arts facilities and Vancouver’s striking neoclassical station, all located in their respective downtowns, this dumpy little one-storey building is about five kilometres from the city centre. But there’s cell service here and so we know that Edson, on the route about three hours farther west, has been evacuated due to a wildfire.

On the other side of the fire are the Rockies, the most anticipated part of the trip. With good reason. Travellers’ impressions of the mountains haven’t changed much since Victorian times. As one wrote in 1887, “[P]eak towers above peak on both sides of the line, carved and moulded by the hand of nature in every possible form of crag and precipice. . . . Words seem too feeble to express or describe the grandeur and solemnity of such scenery.” A contemporary travel writer describes the experience of “speeding through an avenue of fir trees straight for the Rocky Mountains, their eastern flank lit pink by the morning sun,” as “the defining moment of this ride on the Canadian and a sight I will never forget.” Like the Victorian traveller, I’ve found it close to impossible to articulate the sense of awe I’ve felt when I’ve spent time in the Rockies. Not a problem this time.

People’s patience begins to erode after brunch, which normally would have been served after a three-hour stop in Jasper. There are rumours: it’s 60:40 that the train will proceed. The train’s going to turn around, and there’s the option of returning to Toronto. Those of us who are Vancouver-bound are going to be flown there.

This last turns out to be correct. Finally, around 6 p.m., we’re bused to the airport, where Via has impressively conjured plane seats on such short notice. No mountains for us, and no do-overs either. We are no longer on a land cruise; we paid to get to Vancouver, and that’s where we’re going to be delivered. (Still, I imagine the economy passengers being given a piece of cardboard and a Sharpie to make their hitchhiking signs.)

Lucky passengers and staff are booked on an earlier flight. Other employees—the bartender, the guy who made up my bed—manage herding the rest of us onto a later plane and then, in Vancouver, sorting out which hotels we’re billeted at. It doesn’t go smoothly—everyone is deeply disappointed, hungry, tired, and increasingly cranky as the clock ticks toward midnight. I see one of the staffers weeping quietly behind a pillar.

The question of what to do about the perennially money-losing transcontinental service is hardly a new one. In 1959, four years after the Canadian made its inaugural run, the MacPherson Royal Commission on Transportation was struck “to inquire into and report upon the problems relating to railway transportation in Canada.” It was the fourth such inquiry on the issue since the beginning of the century and wouldn’t be the last. The Hyndman commission (officially the Royal Commission on National Passenger Transportation) sat between 1989 and 1992. It had a broader mission: “to establish guideposts for the passenger transportation system that Canadian travellers will use well into the next century and to develop sensible recommendations for the system’s future.”

The MacPherson report was blunt: “[S]ufficient evidence was brought before us to make it abundantly clear that the competition for passenger business from airlines, bus lines and private passenger cars has rendered the railway passenger business as a whole unprofitable.” The more nuanced Hyndman report spent some time considering the “nationalist myth” of train service, noting, “at the real heart of that myth are the transcontinental trains. . . . The attachment to trains is really an attachment to passenger services and in particular to the grand tradition of the Canadian transcontinentals.” The commissioners are apparently unmoved by sentimentality. Their recommendation 4.3 is unequivocal: “[E]ach traveller pay the full cost of his or her travel, and travellers, in total, pay the full cost of the passenger transportation system.”

Clearly, that hasn’t happened. What will be the conclusion of the next commission of inquiry on the matter? Is the fate of the Canadian to become the equivalent of the train that still bears the Orient Express name, a privately run luxury service that links Istanbul and Paris once or twice a year? Imagining themselves sitting next to Hercule Poirot costs passengers upward of $25,000. The last year the historic Orient Express served Istanbul was 1977.

January 17, 1990, was the end of another era: the final day the Canadian travelled the CP route through the Rockies, the one that passes through Craigellachie. The crew had planned to place a wreath on the spot where the Last Spike was driven, but their request to stop there was denied.