Africa is a mess and it’s not going to get better any time soon. That’s the awful truth that’s so hard to face—or to state publicly—for those of us who have had a long, intimate relationship with the continent. Mine has lasted for almost forty-five years. But from the very start, my experiences in Africa began conflicting with my hopes, indicating trouble afoot, foretelling that our utopian dreams were going to lead to crushing disappointments. Of course, we should have known what the entire twentieth century taught: that all utopian dreams fail, not least those wrapped in progressive rhetoric. Still, the reality in so much of Africa has been infinitely more appalling than anything we might have feared.

The regret, disappointment, even the cynicism runs deep, but alongside the many wonderful, committed, and dedicated Africans I know from one end of Africa to the other,1 the struggle for a more just and equitable continent must continue. All too often it feels like a Sisyphean task.

Besides the fear of spreading hopelessness, there’s a genuine risk in publicly facing Africa’s mess. Reasonably enough, Westerners of goodwill want to know how to account for Africa’s apparently endless list of problems. But behind the question often lurks the unspoken implication that the answer has to do with race: are Africans really incapable of governing themselves?

Most people are aware of the African condition: corruption, conflict, famine, aids, wretched governance, grinding poverty. At the time of its independence in 1957, Ghana—the second sub-Saharan African country to free itself of colonial rule and the white hope (as it were) of the emerging continent—was in development terms on a par with South Korea, near the bottom of the scale. Today, the United Nations’ Human Development Index ranks South Korea twenty-eighth among 177 nations, Ghana 138th. For many, this is a vivid and fair symbol of the African record in the past half-century.

I ran into troubling omens from my first immersion in Africa as a graduate student in London in the early 1960s. When I was working on my doctorate at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, one of my friends was Gilchrist Olympio, from Togo, a tiny former French colony in West Africa. Gil failed to appear one day, and on the following day we read in the Times that his father, the first president of independent Togo, had been ousted in the first coup of post-colonial Africa. No one had foreseen the military threat to the new Africa, yet soon enough military governments became as commonplace as the heat.

In white-ruled Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where I was based for part of my doctoral work, a few of us used to unwind at a dance hall in one of the segregated African townships. After two years of teaching, researching, and regularly demonstrating against the government, I was arrested. Later, I learned that the racist security service knew every rocking Congo jive number I ever danced to and that African informers had been paid to keep an eye on us white liberal troublemakers. In Zambia, living by the Upper Zambezi River, the traditional elite of an anachronistic kingdom struck an alliance with South African apartheid leaders against the new nationalist government of Kenneth Kaunda—another shocking lesson to a nice ignorant boy from Toronto. In 1968, back in Canada, I hosted a zapu “freedom fighter” from Rhodesia, only to listen to him viciously badmouth the competing liberation movement, zanu, composed mainly of members of Rhodesia’s other major ethnic group. He could not have detested his white oppressors more. Much later still, I marvelled at another bitter irony—that I had gone to prison in old Rhodesia to help Robert Mugabe become president of Zimbabwe.

From the relative comfort of Toronto, I became deeply involved in a Canadian advocacy group supporting the right of the Igbo people of eastern Nigeria to secede. Soon after independence Nigeria was already in chaos, having undergone murderous coups and internecine conflict among its three main peoples, and now the majority were prepared to starve the entire Igbo “nation” to death rather than allow it to secede. I soon realized that the Igbo never had a chance, and that the leadership, with our blind support, was prepared to see its people starve to death for a wholly chimerical cause.

Ten years on, I was the director of the cuso volunteer program in Nigeria, where more than 200 Canadians served as low-paid teachers, nurses, physiotherapists, and the like. Then, as now, Nigeria’s reputation on the continent was unique, and overwhelmingly awful. Despite many marvellous Nigerians, collectively the country is belligerent, fractious, and always on the verge of erupting into violence. I feared that many of my young wards would return home as confirmed racists. The problem was convincingly explaining to them why Nigeria is the way it is.

Now the task is explaining why almost all of Africa is the way it is. Finding myself plunged into a study of the 1994 Rwandan genocide and its aftermath, the calamitous wars of the neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo, does not make the task any easier. Not much does. I was frequently in Addis Ababa early in this new century as two of the world’s poorest countries, Ethiopia and Eritrea, former allies led by promising new leaders, slaughtered each other’s young soldiers over an economic disagreement. Rural Ethiopia faced a desperate famine, and the government appealed to the world for relief; at the same time, the markets of Addis sold a gorgeous abundance of fresh fruits and vegetables, and in luxury hotels the sumptuous buffets never ran out. During most African famines, people starve because of a lack of money, not a lack of food. In December 2005, I spoke at a series of conferences and marches across Canada about the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda, the quasi-genocide in Darfur, and the instability still threatening the Great Lakes region of Africa. It seems as if the horror stories never stop.

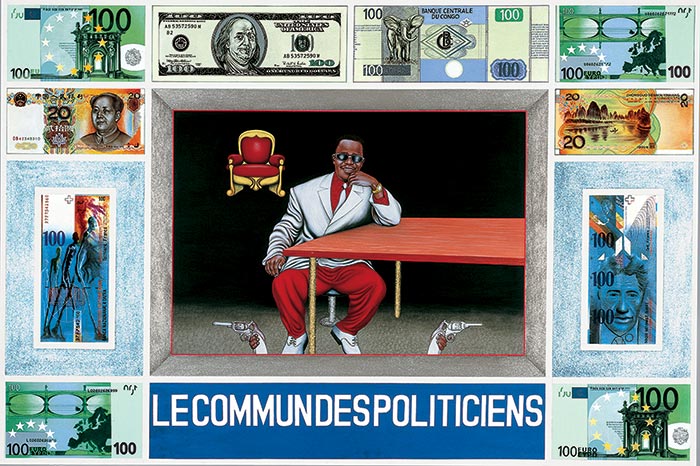

Writing in 2001, bbc correspondent George Alagiah noted that since independence there have been over eighty violent or unconstitutional changes of government, and in twenty countries such eruptions have been repeat occurrences. In A Passage to Africa, Alagiah concludes that it is in the nature of African politics that by the time any such statistics are published they are likely to be out of date. Indeed, over the years African leaders have become synonymous with monstrous tyranny—Mobutu, Idi Amin, Abacha, Bokassa, Sam Doe, Charles Taylor, Mugabe, Habre, Mengistu, Moi, Bashir. The list is very long. It is not possible to calculate the millions of people murdered by these men, or the amount of suffering they caused, or the amount of money they stole: Africans slaughtering Africans, Africans immiserating other Africans, Africans brutally exploiting other Africans. None of this is in dispute.

Nor is the corruption so widely associated with Africa an exaggeration. Police, civil servants, even teachers regularly demand bribes in order to make ends meet on their meagre salaries; the well-connected are just insatiably greedy. According to a much-quoted report prepared for the African Union, African elites steal $148 billion (all figures US) a year from their fellow citizens while national budgets often total less than $1 billion a year. African countries routinely dominate Transparency International’s Corruption Perception indices; predatory African leaders have clearly turned the skill of manipulating political systems to their own advantage into a fine art.

Africa is not a poor continent, and not all Africans are poor. Merrill Lynch’s World Wealth Report for 2006 calculates that there are 82,000 African millionaires—a mere bagatelle out of some billion people, but surely a surprising number nonetheless. Their total worth is $786 billion. But instead of providing moderate prosperity for all, many African nations are the most unequal places on earth. You see it immediately: the gated communities and guarded monster homes of expatriates and local elites right next to mile upon mile of squalid townships with their tiny hovels, filthy water, open sewers, piles of rubbish. Even the rich can’t escape the broken roads, the ubiquitous garbage, the gridlocked traffic, the suicidal drivers, the gangs of feckless young men, the beggars so thick on the ground that even liberals keep the windows closed in their air-conditioned suvs.

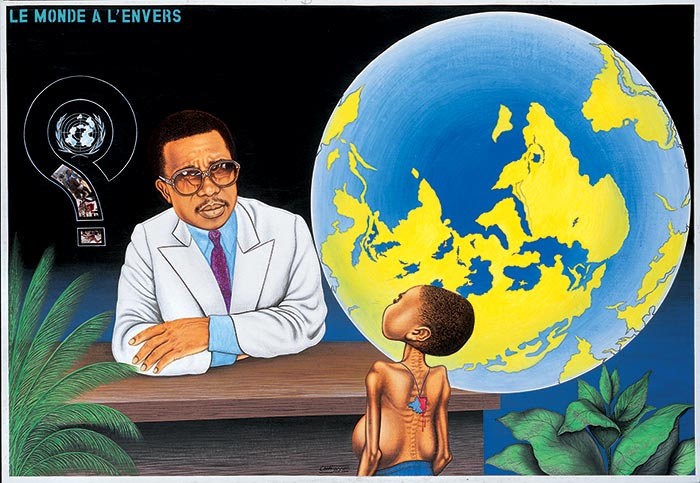

These are the external signs of the larger economic reality. Of the 177 countries on the undp’s Human Development Index, the bottom twenty-four are all African, as are thirty-six of the bottom forty. Most of these countries can’t be expected to improve their lot because they lack the basic institutions and capital needed to develop. Future generations will likely be more numerous, poorer, less educated, and more desperate. According to the Economic Commission for Africa’s flagship Economic Report on Africa 2005, African poverty “is chronic and rising. The share of the total population living below the $1 a day threshold is higher today than in the 1980s and 1990s—this despite significant improvements in the growth of African gdp in recent years. The implication: poverty has been unresponsive to economic growth. Underlying this trend is the fact that the majority of people have no jobs or secure sources of income.”

Forty thousand branches of international aid agencies now operate throughout Africa. Many make a significant contribution through small local projects. Yet as American travel writer Paul Theroux found when he returned to areas where he had worked as a Peace Corps volunteer in the 1960s, virtually everywhere today things are shabbier and less hopeful than they were four decades earlier. Who can resist sharing Theroux’s disillusion about foreign aid or his dour overall view of the continent forty years later?

In the face of these disappointing developments, African leaders continue to bring shame on their countries. South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki and his barking-mad minister of health are undermining serious attempts to deal with one of the world’s greatest aids crises. Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe has systematically devastated his country. In Malawi, which ranks 165 of 177 on the Human Development Index, the newly elected “reform” president chose the huge legislative building for his official residence, bought a half-million-dollar Chrysler Maybach 62 (and, in so doing, kept up with the reckless king of impoverished, aids-ridden Swaziland), and was to have an official portrait painted at a cost of $800,000. Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni, a long-time favourite of the US and Britain and head of state for twenty years, changed the constitution so that he could run for a third time. He had his leading opponent charged with treason and rape. It is as if these men are deliberately seeking to humiliate their continent in the eyes of the world.

Failed or ruined non-states are commonplace. Angola, Liberia, Burundi, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, Central African Republic, southern Sudan, and the Republic of Congo are all emerging from ghastly fighting, all of it internally driven. The challenges each faces even to reach normal levels of African underdevelopment border on the intractable. Conflicts of varying degrees of destructiveness continue in western Sudan (Darfur), between Sudan and Chad, in northern Uganda with the Lord’s Resistance Army, in Somalia, throughout the vast Democratic Republic of the Congo (aided and abetted by Rwanda and Uganda). Nigeria is in a state of imminent implosion. The resumption of war between Ethiopia and Eritrea is a distinct possibility. Across southern Africa, the spread of hiv/aids threatens the very existence of Lesotho, Swaziland, Botswana, and Zambia; South Africa, whose well-being is key to Africa’s future, has more hiv/aids sufferers than anywhere else on earth save for India.

Perhaps the most depressing phenomenon is the situation of girls and women. Many African countries boast the most egalitarian protocols and regulations imaginable promoting the status of women. Rwanda’s parliament has a higher percentage of women members than any other country in the world. Africa has produced a significant number of powerhouse women as well as impressive feminist ngos. Yet the distance between this development and the reality facing the majority of African women seems unbridgeable. In many African countries, in fact, women have no rights at all—they are regarded by customary law as minors, their lives in the hands of their husbands. From legal status to education to manual labour to social obligations to family responsibilities to sexual victimization, life for many, perhaps most, African girls and women is truly Hobbesian.

This portrait, of course, is not the entire reality of Africa today. The continent is endlessly diverse, and all generalizations have exceptions. Hundreds of millions of Africans are just like the majority of people everywhere—hard-working, trying to cope, and full of the multiple complexities of our species. Nonetheless, it’s virtually impossible not to be stunned by the pages and pages of horrid news that constitute the reality of modern-day Africa in a way that’s not true of any other part of the world. In the forty-odd years since my first visit, the dream of a continent that would show the rest of us new possibilities for the human condition has turned into a grotesque nightmare.

How do we account for Africa’s plight and what should be done? The conventional wisdom is that the problem is African and the solution is for the rich, white Western world to save Africa from itself, its leaders, its appetites, and its apparent incapacity for civilization. We give, they take. We’re active and entrepreneurial, they’re passive and dependent. We help, they’re helpless.

There is in this neat equation more than a hint of centuries-old racist attitudes toward Africans, our era’s version of the white man’s burden. But there’s an alternative perspective on the “African problem,” one that is not nearly as self-congratulatory and dishonest. This interpretation says that rather than being the solution to Africa’s plight, Westerners are a very substantial part of the problem and have been for centuries. None of this condones or justifies African malfeasance. But it does help to explain it and to indicate different directions that need to be taken if Africa is to find its path to a better future.

The very notion of Africa as “the dark continent”—dark in skin colour, in obscurity, in primitivism—is a major distortion of historical reality. Over the millennia before colonialism, sub-Saharan Africa was home to a series of great civilizations. Mali, Bornu, Fulani, Dahomey, Ashanti, Songhay, Zimbabwe, Axum—all powerful empires that made their mark on the world. Here is Basil Davidson, the British historian who did much to rescue Africa’s remarkable history from oblivion and Western derision: “The great lords of the Western Sudan grew famous far outside Africa for their stores of gold, their lavish gifts, their dazzling regalia and ceremonial display. When the most powerful of the emperors of Mali passed through Cairo on pilgrimage to Mecca in the fourteenth century, he ruined the price of the Egyptian gold-based dinar for several years by his presents and payments of unminted gold to courtiers and merchants.” No one who has seen the underground churches of Lalibela in northern Ethiopia or the magnificent bronze and brass Ife sculptures of western Nigeria can doubt the extraordinary potential of African technology and creativity. For much of its history, Europe had little to surpass these achievements. We’ll never know the outcome had Africa been permitted to develop based on its own skills and resources, as Europe was, but it was allowed no such luxury.

History matters, and for Africa the slave trade and colonialism matter enormously in understanding its subsequent evolution. In many respects the continent has never recovered from either. Enlightenment Europe had guns and ships, and it unleashed them against Africa. The slave trade ended barely 150 years ago, three and a half centuries in which an estimated twenty million Africans—an astonishing proportion of the continent’s population—were uprooted from their lands. Perhaps twelve million finally arrived alive, and their labour enabled the development of both the United States and Europe, a relationship between Africa and the West that has remained largely unaltered. Arab slavers shipped millions more Africans out of eastern Africa. The continent was left reeling.

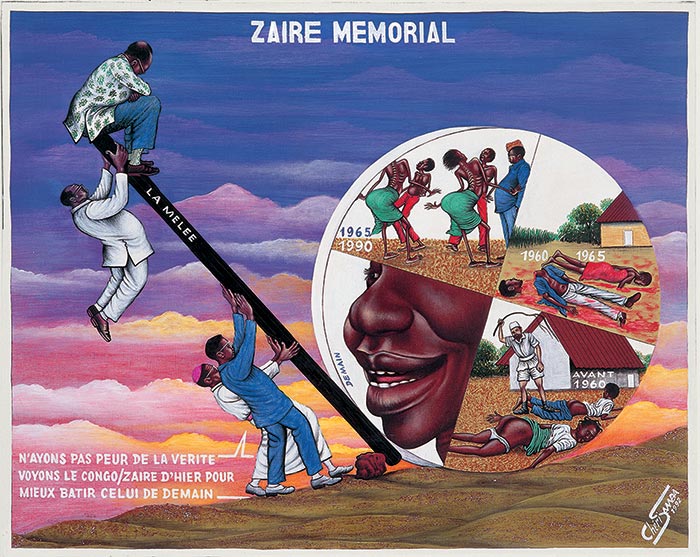

Hard on the heels of the slave trade came full-blown Western colonialism, institutionalized with the “scramble for Africa” at the Congress of Berlin in 1884-85. Undeterred by ignorance and driven by greed and racism, Europe’s leaders blithely partitioned almost the entire continent among themselves. To this day, probably every single border in Africa arbitrarily divides at least one ethnic or cultural group. South Africa has been free from white rule for only a dozen years, and until their very last moments of power, the white minority kept nearly 40 percent of the continent destabilized. From Angola, Zambia, and Tanzania south, no normal governance was possible while apartheid wielded its formidable power. The rest of the continent has been independent for a mere forty to forty-five years, and every country endured colonialism for many decades longer than it’s been independent.

The paternalistic fashion of the moment is to rhapsodize about the good old colonial days. What Africa needs, we are told, is a form of benign colonialism or liberal imperialism. British scholar Niall Ferguson, for example, has gained prominence arguing that imperialism was the greatest thing that could have happened to Africa (and Asia). Nothing could be further from the truth. Colonialism by definition and in practice was based on dictatorship, violence, coercion, oppression, forced taxation, and daily racial humiliation. Not a single colonial power—France, Germany, Britain, Portugal, Belgium, Italy—is innocent. Look at King Leopold’s Congo: half of its twenty million people dead. In the name of bringing civilization to Africa, Belgium introduced the practice of amputating arms as punishment, an abomination replicated a century later by Africans in Sierra Leone’s civil war. The list of atrocities perpetrated by Europeans is long and bloody—Belgian-like tactics emulated in the surrounding French and Portuguese colonies, Germany’s genocide against the Herero people of South West Africa (now Namibia), the blatant theft of land by Afrikaners and Cecil Rhodes’s British-backed gang of marauders across southern Africa, the wars of the British in the Gold Coast, the cruelty of the Portuguese in Angola and Mozambique, the indiscriminate slaughter of Ethiopians by Italy. In today’s terms, every single European power in Africa was guilty of multiple crimes against humanity.

Africa’s partition by European powers was implemented with a fine disdain for existing realities. Families, clans, ethnic groups, and nations were all divided from each other in a purely arbitrary manner. Those unrelated to each other suddenly found themselves locked together under new and alien governments. For many Africans, identifying with these new artificial colonial constructs made little sense; rather than adopting Nigerian or Rwandan or Kenyan nationality, they found it more natural to reaffirm their identities as Yoruba or Hutu or Luo. Paradoxically, then, the imposition by Europe of new nations in Africa served instead to reinforce ties of ethnicity or clan.

In most colonies, with only a tiny number of whites actually on hand, indirect rule prevailed. The European occupier, frequently in collaboration with Christian missionaries, privileged a particular group to help administer the new territory, invariably causing the hapless majority to deeply resent the chosen minority. Together with the meaningless boundaries, such divide-and-rule strategies undermined loyalty to the new nation. Instead, as the end of colonial rule and the emergence of independent African governments drew nearer, the state came to be seen as an ethnic preserve rather than a national entity. Control of the state became the means to reward the rulers’ ethnic followers and to exploit, oppress, or ignore all others.

This phenomenon is still prevalent. Political parties and liberation movements became—and often remain—the instruments of specific ethnic groups. This made untenable the notion of a loyal opposition that could form a new government after winning a free election. It would be tantamount to turning the state over to an illegitimate, antagonistic, and hitherto excluded ethnic group. For the loser, surrendering control of the instruments of the state meant losing everything under a new ethnicity-based government. The role of government came to be seen not as developing the entire nation but as maintaining the loyalty of the rulers’ followers and clients. Political dictatorship became the form of government most appealing to ruling groups. Conversely, violent coups to usurp those dictatorships, often led by factions within the military, seemed the logical means for marginalized groups to dislodge them. Voluntarily surrendering power was unthinkable, sometimes literally suicidal. A substantial chunk of post-independence African history, from the Biafran War to the genocide in Rwanda, can be accounted for in this way.

Much of the tumult that has engulfed Africa over the past half-century results from policies imposed by European powers during the colonial era. All metropolitan governments criminally neglected the welfare of their colonies. Colonies had one purpose only—to serve the interests of the metropole. Only when the spectre of independence finally loomed after World War II was some small thought given to local interests. Even then, until the very last moment, the Belgians in the Congo, the British in Kenya, the French in Guinea, and the Portuguese in Mozambique demonstrated all that was most malignant about colonialism.

Historian Walter Rodney caught the spirit with his powerful indictment of the colonial system, neatly summarized in the title of his 1972 book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. In country after country, independence was ushered in under ethnic leaders pretending to be nationalists, in countries with minimal infrastructure or human capacity, with a heritage of violence and authoritarianism, and through structures that drained Africa’s wealth and resources to the rich world.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the struggle to end colonial rule spread inexorably through the Third World. In the imperial homelands, the anti-colonial movement was one of the great causes of the mid-twentieth century. Progressive internationalists were convinced that independence would open a dramatic new chapter in the history of human emancipation. Africa, especially, embodied the boundless dream of a continent that would show the world how to live without racism, violence, oppression, exploitation, and inequality. But almost everywhere, what in fact followed the raising of national flags was the continued underdevelopment of Africa. An implicit bargain was struck between the new African ruling elites and their old oppressors in Western governments, plus the corporate world, plus the new international financial institutions, to perpetuate old patterns under new circumstances.

Instead of building nations that repudiated the policies and behaviour of the colonial era, the reign of the “Big Men” spread across Africa, bringing with it terrible brutality, bottomless venality, and an almost sadistic callousness. All the while, Africa’s resources continued to pour out of the continent into the coffers of the rich world. The difference now was that the new African elites—whether Jomo Kenyatta and his Kikuyu cronies in Kenya, Mobutu Sese Seko in Zaire, or the new rulers in every one of the former French African colonies save for maverick Guinea—split the plunder with their former Western overlords.

The betrayal by the new elites is not the entire story of the continent’s continuing crises. For centuries Africa’s history and development had been profoundly influenced by outsiders, both Europeans and Arabs, and external influence by no means disappeared with independence. And just as most of the pre-independence impact was exploitative, so has it remained. Yet the conventional wisdom remains the opposite: Africa is the problem, the West is the solution. The Blair commission on Africa, the 2005 Gleneagles summit and the Geldof/Bono singalongs are all manifestations of the West fulfilling its sacred moral obligation to save Africa from itself.

The reality is demonstrably different. The fact is the West is deeply complicit in the crises bedevilling Africa, and we’re up to our necks in all manner of retrograde practices, virtual co-conspirators with monstrous African Big Men in underdeveloping the continent and betraying its people. In almost every case of egregious African governance, Western powers have played a central role. Hardly a single rogue government would have attained power and remained in office without the active support of one or another Western government, primarily the United States and France, with the United Kingdom and Belgium in the game as well. And few of the conflicts that have ravaged the continent would have lasted long without the active intervention of mainly Western governments or, in certain cases, the ussr, including the promiscuous provision of weapons to any and all parties.

Both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher had soft spots for the apartheid rulers of South Africa, who were, after all, passionate fellow anti-Communists; it was Bob Woodward who exposed the close personal working relations between Bill Casey, Reagan’s cia director, and key South African government officials, including its intelligence service. In Angola and Mozambique, the US came in behind Portugal and South Africa to train and arm rebel groups against African governments. To the satisfaction of Belgian mine owners and the US, Belgium conspired with Congo secessionists to murder Patrice Lumumba, the Congo’s first and only democratically elected president. France propped up an array of tinpot tyrants in nearly all its former sub-Saharan colonies, most notoriously the sadistic “Emperor” Jean Bédel Bokassa in the Central African Republic. Virtually all researchers agree that the Catholic Church and the Belgian, French, and US governments bore some of the responsibility for the Rwandan genocide.

Oil companies grow fat from the Gulf of Guinea, increasingly a source of American oil supplies, while the citizens of half a dozen countries go without lights, clean water, good health, and jobs. The US colludes with the government of Sudan in the “war on terrorism,” while accusing that same government of orchestrating a genocide in Darfur. Africa’s most deadly and intractable crisis, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, has its roots in America’s thirty-year unconditional support for Mobutu in Zaire (which is now the drc).

But Western governments, international financial institutions, and transnational corporations do far more harm than merely bolstering and arming tyrannical regimes. Western commercial and financial activities in Africa, as a wealth of research by Human Rights Watch, among others, confirms, are overwhelmingly exploitative and destructive. Research carried out by the well-respected Washington-based ngo Africa Action comes to this startling conclusion: “[Africa] subsidizes the wealthy economies of the world through a net transfer of wealth in the form of payments for illegitimate debts. More money flows out of Africa each year in the form of debt service payments, than goes into Africa in the form of aid.”

Southern African academic and researcher Patrick Bond looked at other variables: “Although remittances from the Diaspora now fund development and even a limited amount of capital accumulation, capital flight is far greater. At more than $10 billion each year since the early 1970s, collectively the citizens of Nigeria, the Ivory Coast, the drc, Angola and Zambia have been especially vulnerable to the overseas drain of their national wealth.” Based on the evidence at hand and contrary to popular belief, it is likely that since the West and Africa first began their multiple interactions, more wealth has drained out of Africa to the West than has been infused into Africa by all Western sources.

In truth, not a single African country has the sovereign right to introduce policies that would significantly direct or alter its own destiny. Governments must either implement the demonstrably failed policies of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank or forfeit aid, loans, debt relief, and general international acceptance. This is the new imperialism, or neo-colonialism, in practice. As noted by prominent American economist Jeffrey Sachs, “The imf routinely works with the finance ministers of impoverished countries to set budget ceilings on health, education, water, sanitation, agricultural infrastructure and other basic needs, in the full knowledge that the consequence is mass suffering and death.” As a Zambian pediatrician told me, for him imf will always stand for Infant Mortality Fund.

Joseph Stiglitz, former senior vice-president of the World Bank and author of Globalization and Its Discontents, calls it market fundamentalism. He means the extreme version of free-market nostrums that the imf and World Bank, backed by Western governments, have unilaterally imposed on Africa over the past twenty-five years. These policies have overwhelmingly failed to grow African economies, but they have succeeded magnificently in increasing poverty and the gap between rich and poor, both between Africa and the West as well as within African countries. Failures when known as Structural Adjustment Policies, these same prescriptions were cynically renamed poverty-reduction strategies with the same destructive consequences.

Forcing Africans to pay for schooling and health care meant that fewer went to school or attended health clinics, an outcome that apparently came as a shock to the experts at the imf and World Bank. Imposing tight ceilings on health and school staff, slashing funds to schools, health clinics, and hospitals, and failing to maintain or expand health infrastructures, have inevitably led to deteriorating health and school systems across the continent. All these deliberately severe austerity programs were imposed at exactly the same moment the aids pandemic was surging out of control. According to the ngo Essential Action, when the World Bank demanded that Kenya begin charging $2.15 for services at clinics for sexually transmitted diseases, attendance fell by as much as 60 percent.

At the same time, Western financiers offered generous loans to African leaders, including the most monstrous among them. Then interest rates rose usuriously, and the debt crisis became yet another component of the African reality. This crisis led to an enormous outflow of scarce capital from Africa to the West, a direct reverse transfer from the poorest of the poor to Western governments and their financial surrogates at the World Bank. According to the UN Conference on Trade and Development, between 1970 and 2002 sub-Saharan Africa received $294 billion in loans, paid out $268 billion in debt service, and yet still owed $210 billion. Even while the G8 industrialized nations were promising debt relief in 2005, African countries had to surrender $23.4 billion in interest and principal payments. The consequence for individual African countries is breathtaking. In 2003, Senegal and Malawi spent about one-third of government revenues on debt-servicing. Angola and Zambia spent more on debt-servicing than they did on health care and education combined.

In a sane world, where commerce yields to justice, much of Africa’s debt to Western institutions and governments would be considered odious and cancelled. Yet not even in the case of Rwanda, where a $1-billion debt was incurred by a government largely responsible for the 1994 genocide, or of South Africa, which inherited a debt of $22 billion from its apartheid predecessor, or in some sixteen other states left unbearable debts by their Western-backed dictators, is there discussion of unconditionally cancelling these debilitating debts. Contrast this with the Bush administration’s successful call for the full cancellation of Iraq’s debt incurred under Saddam Hussein.

The imf and World Bank’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and its successor, the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (g8), have delivered debt relief. However, it amounts to far less than the 100-percent debt cancellation the world was deliberately led to expect. Furthermore, in order to become or remain eligible for debt relief, all countries must comply with the same free-market policies that have already damaged Africa so brutally.

Even when it seems the West is actually investing in Africa, the reality is almost exactly the opposite. With few exceptions, Africa’s fabulous natural riches—from Nigeria to Angola to Chad to eastern Congo to southern Sudan—have become a “resource curse.” Of Africa’s less than 3-percent share of the world’s foreign direct investment, almost all goes to extractive industries—oil, minerals (gold, diamond, coltan, platinum), and timber. Two-thirds of American capital entering Africa goes into mining and petroleum. But to label this “investment” badly distorts the concept. Although there are exceptions, in the majority of cases foreign companies pay little or no taxes, increase corruption by bribing their way to their objectives, build no lasting infrastructures, pay starvation wages, destabilize communities, become involved in local conflicts, then disappear, leaving behind an environmental and social disaster. Last year, the Guardian undertook a major investigation of resource-plundering and corruption in three African countries—Angola, Liberia, and Equatorial Guinea; their harsh conclusions led them to label the situation “The new scramble for Africa.”

The bribes paid by Western companies to loot Africa’s natural resources are useful reminders of what should be self-evident: it would be quite impossible for Africans to steal the quantities involved without outside help. In fact, such bribes are just one component in what Patrick Smith, editor of London’s Africa Confidential magazine, calls “a system run by an international network of criminals: from the corrupt bankers in London and Geneva who launder the money; the lawyers and accountants in London and Paris who set up the front companies and trusts to collect the bribes or ‘commissions’; the contract-hungry Western company directors who offer the bribes and pocket some for themselves.” As Michela Wrong illustrates in her book In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz, the scale of theft carried out by Mobutu suggests his foreign financial backers must have been aware that much of the aid and loan monies intended for Zaire were actually destined for this African kleptocrat’s Swiss bank accounts. The most conservative estimates state that Mobutu had a $50-million nest egg when he ended his twenty-two-year reign. During the same period, Zaire’s debt grew to an astonishing $13 billion.

Natural resources and cash are by no means the only items being drained out of Africa. As it did during the slave trade, the continent is once again giving the West its most precious resource—its best, brightest, healthiest, and most productive people. In effect, African countries are using their meagre resources—often from foreign aid ostensibly aimed at “capacity building”—to train professionals who end up in Europe or North America. Thus, a good chunk of our foreign aid to Africa actually benefits us, not them.

This includes university graduates and professionals in all fields, but is most extreme in the health sector. No African country can afford to lose a single health-care professional. The US has 937 nurses per 100,000 people, Uganda has 61. Canada has 214 physicians per 100,000 people, Ghana, one of the continent’s more stable countries, has 15. Collectively, African countries already fall far short of the who minimum standard of 250 health-care workers per 100,000 people, while the brain drain continues to suck doctors and nurses out of Africa and into the developed world.

At every step, Africa find itself the victim of double standards. The continent is routinely forced to play by the rules of free trade though the West ignores these rules at will. According to ngo Christian Aid, sub-Saharan Africa is $272 billion worse off thanks to the free-trade policies forced on it as a condition of receiving Western money. At the same time, the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (oecd) spend $1 billion a day in agriculture subsidies (mainly to large agribusinesses), allowing them to flood Africa with commodities at lower prices than African producers can match. This protects their own farmers and makes it virtually impossible for African products to gain a foothold in Western markets. Bizarrely enough, it’s now cheaper for a Ghanaian to buy an imported European-raised chicken than a locally raised one. According to CorpWatch, in 1992 domestic poultry farmers supplied 95 percent of the Ghanaian market; by 2001, their market share had dwindled to 11 percent. The pattern has been the same elsewhere; poor African countries lose substantial and sustainable local industries as they are forced to open their markets to cheap imports.

As for the overseas development assistance (oda) that all Western governments include in their budgets, there’s a dirty little secret about all those billions. It’s not just that most countries could easily be far more generous; the real story of oda is how much less has been delivered than almost everyone believes. Many bemoan the billions of aid dollars that have flooded into Africa over the past forty-odd years with precious little to show for it. Now recent research by the British ngo ActionAid, among others, has demonstrated the pathetic reality behind the official numbers. It’s often difficult to determine what constitutes oda in any country’s budget; debt relief, for example, is often lumped in as a form of aid, and some countries still commonly receive aid money for geopolitical rather than developmental purposes, badly distorting the data. Much aid, in fact, directly benefits the donor country, as it is tied to the purchase of goods and services from the donor. This makes little sense in terms of costs or efficiency: food purchased through tied aid, for example, is 40 percent more expensive than what could be acquired through open market transactions. As a result, sub-Saharan Africa effectively loses between $1.6 and $2.3 billion of the annual aid it receives. Though the US and Italy are the worst offenders, Canada is not much better. By most estimates, more than half of all Canadian aid is tied to the purchase of Canadian goods and services.

Tied aid is but a manifestation of a larger category known as “phantom aid.” As described by ActionAid, in addition to tied aid, phantom aid involves a “failure to target aid at the poorest countries, runaway spending on overpriced technical assistance from international consultants, tying aid to purchases from donor countries’ own firms, cumbersome and ill-coordinated planning, implementation, monitoring and reporting requirements, excessive administrative costs, late and partial disbursements, double counting of debt relief, and aid spending on immigration services.” All of these factors deflate the value of actual aid being delivered. Of the $79 billion reported as aid granted by the oecd in 2004, ActionAid insists that only $42 billion was actual aid. In real aid terms, the US spends 0.06 percent of its Gross National Income, less than one-tenth of the UN’s 0.7-percent target. With the exceptions of five small northern European states, the prospect of the developed world ever reaching a real 0.7 percent of gnp in oda is a cruel hoax. Not a single one of the large European countries is even close.

Between meagre aid, phantom aid, tied aid, and aid pilfered by recipient governments, it’s far from evident how much of an impact aid actually makes on Africa. While there’s little question of the benefits aid confers upon the private sector in donor countries, for Africans the consequences of the aid scam, together with other facets of the great collusion between Western and African elites, could hardly be clearer. Africa faces a permanent tsunami, almost entirely ignored by the rest of the world. Every week an estimated 130,000 Africans die of causes that, in most cases, are easily preventable. Four major killers of children are diarrhea, malaria, pneumonia, and measles; for all of these, cheap, safe, available interventions already exist.

To meet their bottomless pit of urgent needs, African governments have available resources so grossly inadequate that it’s almost laughable. Many Westerners travel to Africa with more health paraphernalia than can be found in typical African clinics. When I visited a clinic in Rwanda responsible for the care of thousands of local widows who had been raped and infected with aids during the genocide, there were fewer drugs in its fridge than I had in my hotel room. In Canada, we spend annually approximately $3,000 per capita on public and private health care; Malawi spends $13, Rwanda $7, Ethiopia $5. In Canada, annual drug spending per capita is $681; in Africa it’s two bucks.

Things change. Until 1945, Europe had been a hopeless war zone for millennia. South Korea has changed beyond recognition in the past half-century. China and India are changing. And Africa will change too, though it’s always been Africa’s bad luck that it has no Africa of its own to exploit. What will expedite that change in the right directions?

A facile mantra is now widely recited by politicians both Western and African: African solutions for African problems. At best, that’s only a half-truth. Certainly Africa’s political, business, and professional elites must change. We have a new African Union—the continent’s equivalent of the European Union—which already outshines the shoddy record of its predecessor, the Organization of African Unity, scornfully known as the African Dictators’ Club. But as the disappointing experience of the AU forces in Darfur revealed, it is so dependent on the West for resources and is so divided by all the troublesome African fault lines—French versus English speakers, north versus south, Christian versus Muslim, South Africa versus Nigeria, terribly poor versus very poor—that it will take years before it plays a truly significant continental role. In reaction to Western demands, African governments initiated the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (nepad), described grandly as “a vision and strategic framework for Africa’s renewal.” But since nepad from the first has rested on discredited neoliberal assumptions about growth and development, it is a frail reed on which to rest the continent’s hopes. It’s destined to play a modest role, at best, for the foreseeable future.

The best hope for Africa lies with two developments. First is the increased number of countries that are experiencing political democracy, however tenuously. Second is the emergence of local civil society groups determined to entrench the idea that governments must rule on behalf of all their citizens, not merely cronies and kin. Everywhere, local ngos fighting for social justice, democracy, clean government, gender equity, children’s rights, the environment, the rule of law, and human rights are well placed to have an impact. Many women’s groups and aids support groups play an especially inspiring and often courageous role. Heaven knows it’s a slow, frustrating, dangerous crusade, but you don’t reverse centuries of entrenched patterns and monstrous deeds overnight. If you’re looking for places where funds are well spent, here’s a pretty good bet.

But whatever steps Africa takes, unless the West radically changes its role few positive results can be expected. What we should do is obvious enough: the evidence from success stories beyond Africa tells us that rejecting the dogmas and programs that the World Bank and imf unilaterally impose on poor countries is a sine qua non of successful development and poverty reduction.

If the West were truly serious about helping Africa, it would not use the World Trade Organization as a tool of the richest against the poorest. It would not dump its surplus food and clothing on African countries. It would not force down the price of African commodities sold on the world market. It would not insist on growth without redistribution. It would not tolerate tax havens and the massive tax evasion they facilitate. It would not strip Africa of its non-renewable resources without paying a fair price. It would not continue to drain away Africa’s best brains. It would not charge prohibitive prices for medicines. In a word, it would end the hundred and one ways in which the West quietly ensures that more wealth pours out of Africa each day than the West transfers to Africa.

But that’s the catch. It’s the assumption that we want to help that needs to be questioned. I’ve no doubt ordinary Westerners sympathetic to Africa’s plight take for granted that our policies are meant to help; after all, that’s what they’re invariably told. In the face of palpable reality, rich countries largely continue to insist that their interest in Africa is based on compassion, philanthropy, and generosity. Let the word go forth: the white man’s (and woman’s) burden lives again. Occasionally, our missionary duty becomes so taxing, so exhausting, so damn boring, that we westerners suffer from bouts of “compassion fatigue.” We feel sorry not for those in need but for ourselves. But we pull ourselves together and re-embark on our “civilizing mission”—saving Africa from its leaders, its incapacity, its self-destructive tendencies.

But all this nobility serves to conceal the real obligation of the rich world—to pay back the incalculable debt we owe Africa. We need to help Africa not out of our selflessness and compassion but as restitution, compensation, as an act of justice for the generations of crises, conflicts, atrocities, exploitation, and underdevelopment for which we bear so much responsibility. Many speak without irony of the desire to “give something back,” not realizing the cruel reality of the phrase. In fact, that’s exactly what the rich world should do. We should give back what we’ve plundered and looted. Until we face up honestly to the West’s relationship with Africa, until we acknowledge our culpability and complicity in the African mess, until then we’ll continue—in our caring and compassionate way—to impose policies that actually make the mess even worse.

1 My own direct experiences have overwhelmingly been with Africans from what is usually called sub-Saharan Africa. Arab North Africa seems, in many ways, a separate continent.