One of my earliest memories of growing up in Toronto was my parents telling me, “Lock the door after we leave.” As the eldest of three, this instruction became for me and other urban kids of my generation a mantra for personal safety. Locked doors gave our parents peace of mind when they left us alone. When we lock doors, we feel safer. That is what locks are for.

But locks can make things worse. Locked doors can prevent us from seeing what’s on the other side. How do we know it’s dangerous? What if we’re mistaken? And locks sometimes keep out the hope of being heard at all, of getting a message home, of seeing one’s children, of life getting better. Locks can cause people to succumb to resignation over dreams, to rage over co-operation, to death over life. And locking doors is essentially what prison is all about.

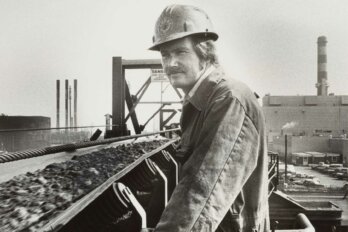

My career in Canada’s federal prison system began in February 1980. I was twenty-four years old and had signed a nine-month contract to work at the Joyceville medium-security prison in Kingston, Ontario, replacing an employee in the gymnasium area. I saw the job as a temporary measure until I could find a teaching job in Toronto, which was my home. As is often the case, however, my plans did not work out the way I expected. I ended up staying with the Canadian federal prison service. Over the next three decades, I worked inside seven different federal prisons in Ontario, at all three levels of security, including both of the maximum-security prisons in the Kingston area, Millhaven and the now defunct Kingston Penitentiary. One reason I moved around so much was that I rose through a series of promotions; the other reason was curiosity.

The vast majority of this thirty-year career was spent working right on the front lines, in the cellblocks and other areas where staff and prisoners interacted every day. I was down inside among prisoners and staff in every facet of prison operations. I locked and unlocked cells, completed prisoner counts, and took prisoners to the hole (solitary confinement) against their will. I took four or five prisoners outside the prison on work details by myself, conducted strip searches, and put out fires on the ranges (hallways of cells) following a murder. At Christmas, I allowed some prisoners phone calls home and declined to release others. I played hockey with the prisoners in a maximum-security prison yard and sat in a tower with a rifle overlooking the same yard. I consoled prisoners when their mothers died. I had a prisoner grab me by the throat, and I had my life threatened more times than I can remember. I had coffee poured for me—and urine thrown at me. I saw a lot of blood.

I met prisoners in maximum security when they carried a shiv (homemade knife) for protection and again in minimum security when they were close to release. Later still, on the outside, I met these same men in grocery stores, and they introduced me to their wives and children. I have interviewed literally hundreds of prisoners in every conceivable scenario, read hundreds of prisoner files, and written hundreds of reports for prisoners to be released, paroled, and sent up to higher security or down to lower security. My reports allowed prisoners to spend time with their families in the community—and I took those men home for the day.

But the strain of working in this type of environment for many years took a heavy toll on my personal life. For thirty years I suffered bouts of personal angst and uncertainty regarding the true nature of prison and its purpose. Many times I considered resigning from the prison service. I experienced innumerable sleepless nights and moments of despondency and resignation, leading to stress leave, alcohol abuse, and divorce.

Stephen Harper’s Conservative government’s tough-on-crime agenda helped to prompt my retirement in 2009. When I saw the changes being advanced to make our prison environment more closely resemble the US model—changes I considered unconscionable—I knew I would be unable to participate. I was aghast at how readily the leadership of the CSC embraced these draconian measures, seemingly without any hint of moral conflict.

If the true goal of prison is to reduce the likelihood of prisoners committing further crimes when released, then it follows that another goal of prison should be to maximize the likelihood of positive change, individually and collectively. What I’ve learned in my thirty years “down inside” is that humane treatment is the most effective way of managing a prison safely and creating conditions to rehabilitate prisoners. The more humane the environment, the safer for all concerned, prisoners and staff alike.

We must begin by unlocking doors and discovering who and what we are really dealing with.

Prison isn’t quite what you see in the movies, full of men with bulging biceps covered in tattoos. Prison is more like a volatile version of greater society. You can find every kind of person imaginable incarcerated. There are men who spend their days lifting heavy weights, while others paint with watercolours. Some prisoners play bridge while others share dirty syringes, the modern equivalent of drinking moonshine or sniffing rags soaked in paint thinner. Most days in prison are fairly quiet, and everything seems to roll along without much bother.

But prison is a place where violence is often the first recourse to solve a problem, and as I would learn quickly, the level and degree of violence are frightening. During my time, acts of savagery and cruelty occurred that I would not have thought possible. Who would believe that a man would gouge another man’s eyes out with a pencil for looking at his girlfriend in the visiting room? Or swing a metal weight-lifting bar at another prisoner and take the top of his head off? Another prisoner lost all his teeth to an iron bar for talking on the phone too long; still another had the soles of his feet slashed for walking on a freshly waxed floor. A man on my caseload was stabbed to death while lying on a bench lifting weights on a Sunday morning, possibly in a case of mistaken identity.

It is difficult to understand what would motivate a man sitting in a filthy prison cell to draw with a dirty syringe the infected blood of his male lover and inject it into his own arm as a show of love and commitment, or to strip and cover himself in his own feces before crawling under his bed and refusing to come out. The CSC acknowledges that a large percentage of those incarcerated suffer from one or more diagnosable mental illnesses. This alone makes the environment within a prison difficult to manage; addiction, poor impulse control, mistreatment at the hands of staff, gross negligence, and confinement in a dangerous environment make conditions even worse.

What is less well known is the vast majority of those who are incarcerated for victimizing others have themselves been victims. Having read many prisoner files and conducted many interviews, I say this with certainty. Most of the prisoner files I read contained histories of physical, emotional, and, often, childhood sexual abuse. Their life stories typically follow a similar path through the quagmire of social services, foster homes, training schools, and young offender facilities. These very damaged human beings have usually suffered unspeakable horrors that began in the earliest years of their existence and left them unable to feel or care about the values on which most of us predicate our lives.

The corrections system employs many fine people, and they deserve great credit for doing their best every day under often impossible circumstances. These gifted staff members include uniformed guards, shop instructors, chaplains, parole officers, nurses, rehabilitation program staff, managers, and school teachers. They are the unsung heroes of Canada’s prison service; their presence makes our prisons safer and more humane. Regrettably, they make up a small percentage of a prison’s total workforce.

In my opinion, too few prison employees care about the prisoners under their care, other than to make sure they are alive and behaving. Any interest in a prisoner’s well-being and their chances for becoming a law-abiding citizen is almost non-existent. Some prison employees seem to regard the prisoners as less than human and feel it is acceptable to mistreat them in myriad ways, ways they would not even consider outside of prison and that they would be ashamed to have their family and friends see. Some employees engage in acts that would be a crime outside the prison walls. Many more of these acts are simply crimes of the conscience: racism, verbal and emotional abuse and intimidation.

I believe a culture of collective indifference toward both the prisoners and CSC’s stated higher goals has crept in and become as cemented in place as the stones in the walls of Collins Bay penitentiary. This culture is, in my opinion, largely responsible for most of the problems that occur within our prisons.

Sadly, the organization itself unofficially almost sanctions the mistreatment of prisoners. Many of the people at the top will not risk poor relations with staff or their unions in order to ensure every prisoner’s rights are respected. The “blue wall” is perhaps the most disturbing element in this living drama. The term is commonly applied to policing, but it is very much part of the Correctional Service culture. The blue wall is an overdeveloped sense of solidarity, a level of cohesiveness that transcends one’s personal values. The unspoken rule is “never rat on a fellow officer, no matter what.” This unofficial oath of secrecy can be found from the tiniest corner of any prison shop to the highest halls of power in Ottawa, and everywhere in between. And it prevents Canada’s penal system from exercising complete control over its prisons.

Justice Louise Arbour encountered the blue wall when she led an inquiry in 1996 into practices at the Prison for Women in Kingston. “The deplorable defensive culture that manifested itself during this inquiry has old, established roots within the Correctional Service, and there is nothing to suggest that it emerged at the initiative of the present Commissioner or his senior staff. They are, it would seem, simply entrenched in it,” Arbour wrote.

Imagine that you’re a new correctional officer, a guard, who has been working at a local prison for three months. You’ve met many of the staff and are beginning to feel like part of the group. Sometimes you go for a beer with your colleagues after work. Perhaps you’re finding working in a prison much more challenging than you originally imagined. One evening, while working in the solitary-confinement unit, you witness an argument between an irate prisoner and a fellow officer. The prisoner is verbally abusive, and the officer, your colleague, is showing increasing signs of frustration. Finally, the officer orders the prisoner back into his cell. As the prisoner turns around to enter the cell, the officer places his hands on the prisoner’s back and shoves him from behind. The prisoner, unprepared for the push, stumbles forward into his cell, banging his forehead on the steel door frame. The officer who pushed him did not intend for the man to hit his head; in fact, he may have regretted giving in to his frustration at the moment it happened. But now the cell door is closed and locked, and the prisoner is screaming at the top of his lungs that a staff member has assaulted him. He demands to see the nurse, the unit manager, the warden, his lawyer, and so on.

Having regained some composure, the officer responds, “I didn’t push you. You tried to punch me, and you slipped!” With that, he returns to the office.

At some point in the shift, the correctional manager, the most senior person on duty and in charge of the institution for the evening, stops by on his regular rounds. When he hears the yelling, he walks down the range to speak with the irate prisoner. Then he comes to the office where you are sitting with your two colleagues, and he asks about the prisoner’s allegation. The officer involved insists the prisoner took a swing at him and slipped, hitting his head on the door frame, and the other officer present supports his version. The correctional manager reminds everyone to submit a written situation report before they leave work. You now find yourself alone in the office with two of your more experienced colleagues. What would you do?

Chances are, at the end of the shift three or four separate reports will be submitted, all giving exactly the same version of events: the prisoner slipped and hurt his head while trying to assault an officer. This version will find its way into many places and many hands, including the prisoner’s parole officer. The prisoner could be in for a whole different kind of trouble—higher security, a longer sentence, or worse, and the officer responsible for his injury will escape any consequences for an act that, outside prison, could well be a criminal assault.

I don’t doubt that many employees who adhered to the code found it tested their conscience at times. Over time, I saw many employees start out eager to make a difference, only to later fall in with the staff who had decided the prisoners under their charge were unworthy of their time and energy. They became indifferent to—even annoyed with—the prisoners’ myriad needs. They started to ignore written requests and complaints. They might review unfairly or incompletely a prisoner’s eligibility for employment, educational programs, parole, or alternatives to solitary confinement. In its most severe form, verbal abuse and excessive force became routine. The prisoners could have, in turn, responded with anti-social behaviour that only validated the belief they were incapable of change and undeserving of better treatment. Sometimes this thinking gave rise to the conviction that harsher treatment would solve the problem, even if this meant bending or violating the rules governing the treatment of prisoners. Sadly, direct supervisors and some senior managers did not always discourage this response, even though it was clearly illogical and illegal.

I once encountered a young and relatively inexperienced parole officer, recently and temporarily promoted from uniformed officer, who recommended a particular prisoner on his caseload receive an order of detention from the National Parole Board (known as the Parole Board of Canada as of February 28, 2013). As a rule, only a very small segment of the prisoner population, the extreme high-risk offenders, receives these orders, which mean they will remain incarcerated until the expiry of their full sentences. Referrals for detention are considered extraordinary action, justified only in cases of extreme violence, and/or exceptional circumstances, such as compelling evidence that the prisoner is planning to commit, or likely to commit, an act causing death or serious harm upon release. This particular case did not meet the legal criteria for a detention referral; it was not even close. Not only was there no compelling reason to assume the prisoner would commit an act causing death or serious harm upon release, but also there was no evidence that this prisoner had been involved in significant violence at any time in his history.

I was acting warden at the time, and I declined to support the parole officer’s recommendation. At first I put it down to a mistake: a new parole officer had misinterpreted the admittedly complicated legal parameters that govern detention referrals, and, somewhat inexplicably to my mind, the unit manager, the coordinator of case management, and the parole officer’s own unit review board all failed to reject the recommendation before it came before me at the detention review board.

Had our quality-control system broken down? No. The answer turned out to be much more mundane, and much more frightening. This prisoner didn’t meet the detention criteria, but he met and exceeded the pain-in-the-ass criteria; the parole officer had decided he should stay in prison. His unit manager was not trained in risk assessment and was a like-minded former guard and a friend, the two having worked together in uniform earlier in their careers. The coordinator of case management told me she was just “keeping the chair warm” and didn’t want to “rock the boat.”

All of these people were prepared to look the other way while a prisoner potentially had years added to his time behind bars, and it would have been a mistake — a mistake permitted because one employee saw an opportunity to abuse his power and others were unwilling to speak up.

The blue wall endures because prison employees form a tight bond forged by the considerable challenges of their unique work environment. Uniformed staff often see themselves as set apart from the other employee groups, literally as well as figuratively. Only another officer can appreciate the anger and frustration one feels when a prisoner throws urine in your face or spits on you or bites you. It can be difficult to take the high road, and when management appears indifferent to the challenges you face, it can understandably seem that only other officers share your feelings.

One of prison staff’s chief complaints was the misperception that the higher-ups routinely and unfailingly gave in to the prisoners. This view was widely held during my time and prevails today, from what I hear. Many employees (and Canadian citizens, for that matter) see prisoners as having too many rights. This is a very tough nut to crack. Logical arguments predicated on an understanding of the Charter do not suffice in this arena.

Most Canadians are familiar with the former federal government’s position that a tough-on-crime approach is the most likely to reduce crime and deal with those who engage in anti-social acts. Many people argue that if prison is tougher people will stop committing crimes to avoid going back.

My experience convinces me otherwise; this argument is extremely flawed and represents an overly simplistic view of the causes of crime. We need look no further than our neighbours to the south. The United States prison system is firmly rooted in a philosophy of longer sentences, secure custody, and harsh treatment, and this approach has been utterly ineffective. In fact, ample evidence suggests it has had the opposite effect. As Henry David Thoreau once wrote, “There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who strikes at the root.”

In my experience, if the staff is humane and reasonable, prisoners are better behaved, and the prisons are generally orderly and stable. Those prisons with the fewest locked doors are also the prisons that experience the fewest problems. Safer environments are the direct result of staff and prisoners interacting face to face regularly. The more often prisoners are exposed to the habits and behaviours of socially adapted people, the more they learn to adopt the same types of behaviour. They see and accept that such interactions are positive and life-affirming. For many prisoners, this is their introduction to a world that is not always negative and dangerous, a world where they may, for the first time in their lives, begin to trust others.

Some of the many victims of crime, their lives permanently changed by terrible events, may not feel sympathetic to my argument for the necessity of humane treatment. The parents of the young girls Paul Bernardo murdered, or the survivors of his numerous sexual assaults, may misconstrue my words as evidence of a casual and sympathetic bias toward the convicted. Nothing could be further from the truth. One of the most difficult periods of my career was the six months I spent as the victim services coordinator at a minimum-security prison, responsible for advising victims of events in prisoners’ cases. This assignment put me in direct contact with many victims of crime who, I know, relive every day the fear, pain, anger, and humiliation they felt when a crime was committed against them. Listening to another person describe a terrifying and life-altering event left me so emotionally drained that I was often numb for many hours afterward. Some of my conversations with victims caused me to doubt and question, for the first time, many things I thought I believed in, like redemption and second chances.

Although I experienced troubling moments of disillusionment in my career, I remain convinced any government policy that doesn’t make rehabilitation the central focus of its prison system is doomed to fail.

In every prison I worked in, I always tried to make myself available to prisoners who had problems they could not get resolved at lower levels, including prisoners from cellblocks where I did not hold jurisdiction. When I’d ask why they brought their problem to me instead of their unit manager, they’d say, “No one else will help me. A couple of guys said I should ask you. They said you’ll tell me straight.” I knew this unresponsiveness was probably true, and it caused me untold frustration. I’ve lost track of how many times I was able, with one phone call, to solve a problem for a prisoner who’d been banging his head against a wall for weeks or months—a symptom of the inertia that pervaded much of the prison system.

I actually enjoyed visits from the prisoners, and I knew it meant a lot to the officers who worked face to face with them and often bore the brunt of the extreme frustration caused by bureaucratic bungling and, in too many cases, the sheer laziness of prison staff. Over the thirty years I worked in prisons, a great many men sat in the visitor’s chair, or as I liked to call it, “the chair” in my office. The crimes of some had dominated headlines around the country. Others were wretched, forgotten souls who only wanted to survive their present circumstances. Whoever they were, they came because they believed they needed my help. Such problems could be extremely delicate, especially if a review of the circumstances revealed the prisoner was indeed being mistreated or ignored. That happened a lot, unfortunately.

Some prisoners submitted a complaint and never received a formal response, or, equally frustrating, were told in writing, “Your grievance is denied,” when I could clearly see they were right and their grievance should have been upheld. Sometimes prisoners who had submitted applications for things like transfers, temporary absences, and private family visits had their applications ignored. One prisoner from another unit came to me because he had been waiting six months to have private family visits with his wife and daughter. I confronted the parole officer who was ignoring the man’s application. Later I learned that same parole officer recommended against the proposed visits, in direct contravention of policy, as payback to the prisoner for complaining to management. I, as acting warden, went into the system and changed the final decision to “approved,” diplomatically noting the “incorrect” policy interpretation.

These small problems can escalate if they are not corrected. Sometimes I just wanted to shake everybody and say, “Do not forget: they outnumber us four to one.”

“Introduction” from Down Inside: Thirty Years in Canada’s Prison Service. Copyright © 2017 by Robert Clark. Reprinted by permission of Goose Lane Editions.