When shorn street fighters with cauliflower ears, superior sensorimotor abilities, and balls to spare beat the living piss out of each other in an octagonal cage at Toronto’s Rogers Centre this May, the marquee event stands to generate $40 million in economic activity. Nevertheless, the province’s decision last August to welcome the Ultimate Fighting Championship—the promotional behemoth that drives mixed martial arts’ global popularity—has been met with a chorus of “There goes the neighbourhood.” As Stephen Brunt quipped in the Globe and Mail, “the barbarians are at the gates, or at least at the retractable roof.” Susan G. Cole at Toronto’s weekly NOW magazine offered her own sound bite–sized shibboleth: “Positively pukeworthy.”

At the heart of the moral panic lies a lament for one of Canada’s more spectacular, if no less stupid, pugilistic traditions. Because “unlike professional wrestling,” as Cole submitted, “mixed martial arts sport has no humour, no theatre, nothing but unadulterated violence, albeit skilfully deployed.” Even for those of us who don’t regard UFC as the first lurch toward a Running Man–style dystopia of high-stakes competitive blood sports, its popularity does make one pine for the pageantry of pro wrestling.

Home and native land to Calgary’s Hart Foundation, Saskatoon’s “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, Vancouver’s Velvet McIntyre, and Hamilton’s Love Brothers (a duo of tussling peaceniks dolled up in tie-dyed headbands and bell-bottoms), Canada has long been a mecca for professional wrestling, with the sweat-smacked canvas of Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto serving as de facto Taj Mahal. From the early ’50s to the mid-’80s, the Gardens hosted Maple Leaf Wrestling, the promotional body responsible for booking, scripting, and stage-managing key Canadian bouts and building its biggest stars.

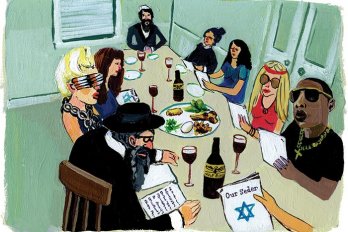

Wiretap

Riverdance devotees learn not to ask questions

Peter Ryan

In June of 1998, fans of the musical sensation Riverdance were shocked to learn that the taps of the dancers’ nimble feet were partly pre-recorded. The news set off a worldwide media frenzy, inciting comparisons to Milli Vanilli. The producers scrambled to do damage control, claiming there was nothing inherently dishonest about using “special audio effects” to “augment” live performances, while the show’s executive producer, Julian Erskine, argued that Riverdance’s popularity necessitated the use of “click track” technology. Fans, he argued, had put the company in a double bind: they were attending the show in increasing numbers, thereby requiring larger venues, but they still wanted to hear all of the taps and stomps only audible in more intimate settings. Click tracks satisfied consumer demand. Whether or not you buy Erskine’s response, he had a point: Riverdance was one of the most popular productions on earth. Months after the scandal broke, Radio City Music Hall reported that ticket sales hadn’t decreased in the slightest. Today, a Riverdance publicist claims the organization has never received a single letter of complaint about the issue.

—Simon Lewsen

As in a classic Western, where the bad guys and the good guys are distinguished by their black and white Stetsons, Maple Leaf Wrestling presented a world in which villains were vanquished; heels humiliated; and the idols, underdogs, and “faces” (short for “babyfaces”) emerged as victors, their status as popular folk heroes bolstered by their Bunyanesque proportions. Like most forms of pro wrestling enjoyed worldwide (be it Japan’s puroresu or Mexico’s lucha libre), it was more sideshow than sport, a deeply moralistic dramaturgy unfolding via the chokeholds, cheap shots, and beatdowns of mock combat.

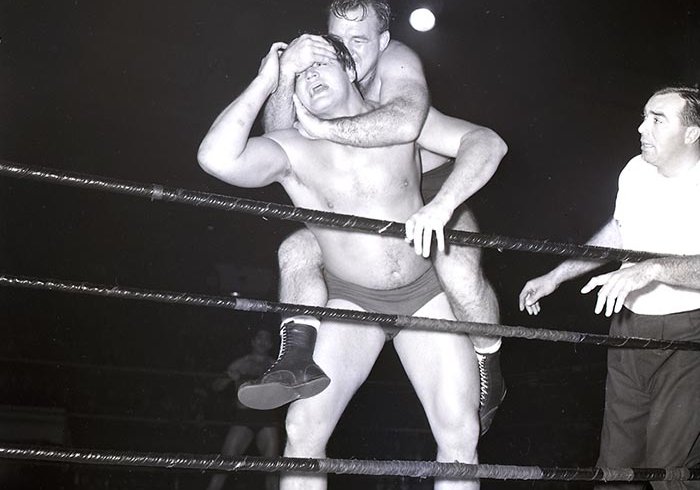

Take the bout that unfolded at the Gardens on March 12, 1959. Toronto superstar “Whipper” Billy Watson—a dead ringer for the old-time carnival strongman, down to the debonair Errol Flynn moustache—squared off against flamboyant Yankee pretty boy “Gorgeous” George Wagner. Watson had pledged to retire if he lost, while Wagner wagered the platinum blond locks that put the “Gorgeous” in “Gorgeous George.” No world titles or championship belts were at stake. The singular aim was to entertain.

In due course, the local boy seemed to have triumphed, subduing Wagner with his trademark sleeper hold, the Canuck Commando Unconscious, when long-time rival Gene Kiniski stormed the ring. (Never mind how he happened to be there.) The hard-assed drill sergeant type pounced on Watson, but the move backfired, resulting in Wagner’s disqualification. As if on cue, a procession of babyfaces emerged from the dressing room to chase off Kiniski, and helped the referee pin the loser as the Gardens’ barber razed his resplendent mane for an audience of 14,000.

Anyone who has spent even one Saturday afternoon parked in front of the television watching wrestling is more than familiar with stunts like these. They’re part of what the industry calls “kayfabe”—a kind of pig Latin translation of the edict “Be fake.” But the word doesn’t merely describe the meticulously misplaced elbow drops and counterfeit convulsions that signal serious injury. It implies a suspension of disbelief. It’s the unspoken agreement among promoters, performers, ringside announcers, and fans to regard all the events taking place as if they were real.

“Kayfabe” is what Cole and others are talking about when they talk about the humour and theatricality of wrestling, and it’s what made Maple Leaf Wrestling saleable, not to a niche market of meatheaded muckers, but to the culture as a whole. “Everybody watched wrestling,” says Greg Oliver, author of The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Canadians. Not that it wasn’t violent. Watson himself suffered five broken noses, some 250 stitches, a dislodged eyeball, and various other discomforts throughout his thirty-five-year career. But “kayfabe” elevated it. “Wrestling,” Roland Barthes wrote in his seminal text Mythologies, “presents man’s suffering with all the amplification of tragic masks.”

Of course, it didn’t hurt that there wasn’t much else on television on Saturday afternoons back in the golden age of Maple Leaf Wrestling. When programming exploded in the early ’80s, Vince McMahon, CEO of the US outfit the World Wrestling Federation, began aggressively syndicating slicker matches across North America. By 1984, he’d seized the Maple Leaf Wrestling brand, and while many Canadians would rise to stardom under his management, Canada’s pro wrestling broadcast was all but history.

The Ultimate Fighting Championship is positioning itself to fill the gap, opening a Canadian headquarters in Toronto (run by former Canadian Football League commissioner Tom Wright), but beef and bloodied noses alone aren’t enough to wad up the void. We can will these brawlers to win. But we can only wish them to be funny. To be theatrical. To be goofy. And, above all, to be fake.

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.