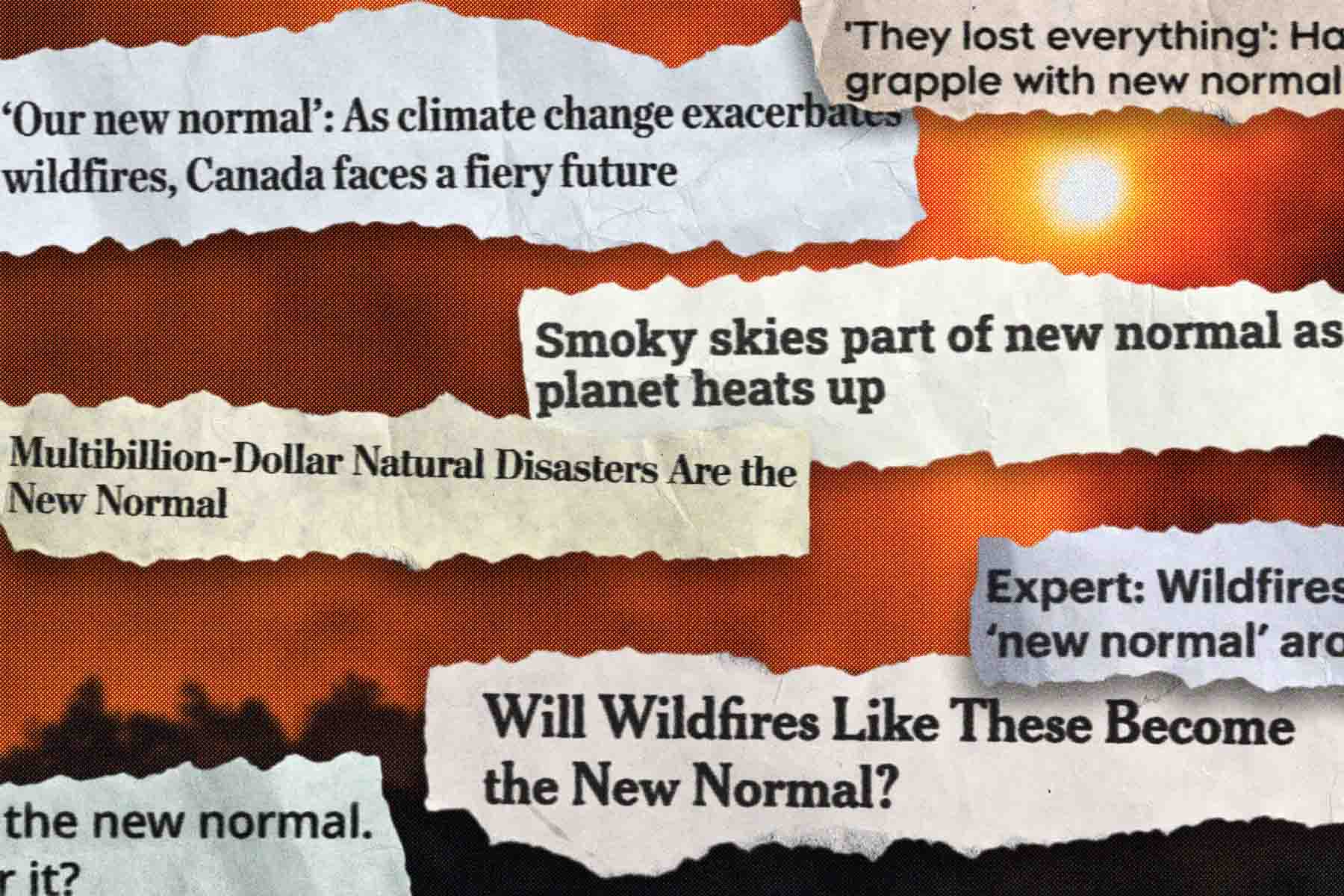

It’s become an annual affair: at winter’s end, when floods and wildfires spread across the land, talk of “the new normal” sprouts into public discourse like mushrooms after rain. This year’s been true to form: when Alberta caught fire in early May, commentators across the media landscape deployed the phrase with abandon. Two weeks later, unprecedented flames roasting the outskirts of Halifax inspired the same response from editorial cartoonist Michael de Adder. By the first week of June, talk of the new normal had followed the boreal’s smoke all the way to New York City.

These days, the most frequent context for the term is climate change. But the new normal’s popular history, though brief, predates the rise of wildfire smoke–enshrouded cities.

The precedent for getting used to the unprecedented was established two decades ago, in the wake of 9/11. (The term does appear sporadically throughout twentieth-century commentary, but not until the fall of the Twin Towers does it take root in the public imagination and become a recurring catchphrase.) In his 2022 book, Political Catchphrases and Contemporary History: A Critique of New Normals, the literary scholar Suman Gupta traces the first significant use of the term back to a speech then US vice president Dick Cheney gave on October 25, 2001, when he warned Americans to brace themselves for decades of heightened government surveillance. “I think of it as the new normalcy,” Cheney said. There may be no better slogan for the twenty-first century.

It didn’t take long for newer, bigger normals to proliferate. Paranoid security measures gave way to the financial crisis of 2007/08, which yielded to Donald Trump (“Why is lying the new normal?” asked Vanity Fair in 2017). Around the same time, a wave of terrific wildfires covered western North America, providing more kindling for the new-normal narrative. In 2018, the British Columbia government released an independent report called “Addressing the New Normal: 21st Century Disaster Management in British Columbia,” which neatly summed it up. The following year, a report on the Colorado river’s terminal decline by the Yale School of Environment declared “Drought Is the New Normal.”

As the 2020s approached, it looked like climate crises had bought exclusive rights to the phrase. But then the pandemic came along and hijacked this narrative along with all the others, delivering an entire subgenre of new normals that dovetailed nicely with 2020’s US election misinformation, another phenomenon we’re told is novel and here to stay. The term has proven highly adaptable, as it urges us to be.

New normals are here to stay. You can almost hear the sales pitch sing itself. Beyond the selling of books and news articles, however, new normals are distinctly anti advertorial. You don’t use them to celebrate improved living standards or the recovery of humpback whale populations but only and always to normalize some unpleasant state of affairs, once novel and fleeting, that has settled into permanence. New normals convey a single, grim message: get used to it.

In 2023, despite the competition, it appears climate change has clawed its way back to the top. “The new normal” once again refers most frequently to climate disasters, which, over the past five years, have demonstrated a staying power few other emergencies can dream of. With a new El Niño bearing down and civilization burning more fossil fuel than ever, the coming years are going to test our imagination like never before. The temptation to say “the new normal” will grow with each catastrophe, but every time we use them, those words mean a little less.

And that, obviously, is the problem. The term has become a cliché. It has lost its power to startle and evoke. What began as a useful expression for jolting an audience into noticing something—Whoa, this formerly unprecedented awfulness is now a defining condition of daily life; maybe we should respond!—now has the opposite effect: it prevents us from taking notice. It’s become a soporific. “The new normal” has itself been normalized, and so has the thing it describes—in this case, climate change.

But normalization is the worst possible response to climate change, short of denial.

Powerful interests, like Big Oil and its political representatives, know this very well. That’s why, as denial becomes increasingly untenable, they have started telling us to “get used to it” instead, to accept there’s no point in burning less oil or consuming less meat—all we can do is adapt to an age of chaos, build dykes and border walls, beef up the police.

Exhibit A in this transition from denial to normalization is Florida governor and US presidential candidate Ron DeSantis, who signed a bill in 2021 to spend $640 million (US) on preparations for rising seas, floods, and storms. Never mind the piteous sum (2018’s Hurricane Michael alone cost Florida more than $18 billion in damages), DeSantis is using adaptation as an alternative for doing anything about the actual cause of rising seas. When asked whether his administration intended to fight climate change itself, he would only say, “We’re not doing any left-wing stuff.”

You hear the same approach from Canadian Conservatives. When Pierre Poilievre was asked about the creation of a national wildfire service during a press conference on June 5, the leader of the federal opposition responded: “We would be open to studying any solutions that will help the country better coordinate its water bombers and other [firefighting] assets.” There was no mention of the root causes of wildfires.

It’s not that he’s wrong to emphasize the need for disaster preparedness. We’re going to need all the firefighters, dykes, and cooling stations we can get in the weeks and years ahead. But the reason these disasters have reached their present unprecedented scale is that people like Poilievre and DeSantis have spent their careers downplaying the severity of the climate crisis. Now smoke is blanketing the continent. So long as Conservatives, Republicans, and their counterparts around the world keep urging society to increase its consumption of fossil fuels, the scale of these disasters will increase in lockstep.

It doesn’t have to be this way. There’s still time to stop the climate crisis from metastasizing into a global meltdown—every hundredth of a degree of warming we avoid matters. But whether this decade marks the peak of the climate crisis or merely the beginning will depend on who and what we pay attention to.

That’s why seemingly innocuous phrases like “the new normal” matter. Language matters. It guides our attention, inspires certain courses of action while preventing others. It is the lifeblood of democracy, where policy flows from conversation and debate instead of force.

The twenty-first century has already become the age of ecological catastrophe. That’s new and noteworthy, even twenty-three years in. The one thing it isn’t, the thing we must fight to prevent it from becoming, is normal.