In a few short weeks, traffic in downtown Toronto will turn especially vicious. Stretch limousines will ferry the leaders of nineteen countries and the EU through the cordoned-off streets, along with their security details, policy advisers, press spokespeople, and assorted experts and hangers-on. Journalists by the thousands will converge on the city to observe, describe, dissect, and pontificate about what the leaders do or don’t decide about the global economy and, during downtimes, about what they eat and wear.

The pandemonium will be preceded by a comparatively quiet meeting in Muskoka of the leaders of the “old” big powers—the United States, Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, Japan, and Russia. After dinner and a morning session on international security and development, they’ll come down from the mountain to meet the “new” big powers, including India, China, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia. When they do, they will be making history.

Never before have the two summits—the G8 and the G-20—been held together, and their coupling marks a shift from the past century to this one. When France created the Group of Six thirty-five years ago, in the wake of the oil shocks and the subsequent global recession (Canada joined a year later), the member countries produced enough of the world’s goods and services and controlled enough international trade to make their stewardship of the economy credible. Their annual meetings were short and informal; leaders talked to each other directly, over local food and local wine, in an effort to get the job done.

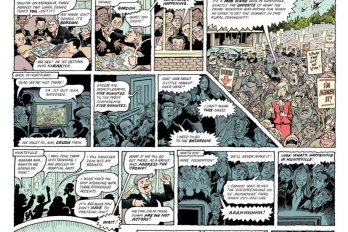

Old Boys’ Club

The dream of an integrated Global Freemasonry

Any governing power bloc has to adapt to changes in the political, economic, and social order. The same goes for shadier sectors of extra-governmental authority. While traditional Freemasonry remains a fraternal order, with women strictly barred from lodges, many women have found homes in fringe Masonic institutions. Operating outside of the restrictive parameters of the Grand Lodge boys’ clubs, women interested in the ancient rites have taken up membership in female and mixed-gender orders such as the Daughters of the Nile and the Order of the Eastern Star. Some Masonic scholars have even argued that these organizations have a sacred precedent. The Regius Poem, a foundational text laying out the moral duties of the Freemason, states that “there shall no master supplant another, but be together as sister and brother.”

Toward the end of the ’90s, however, it became apparent that “emerging markets” had emerged, and the G8, which now included Russia, began inviting the “Plus Five”—Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and South Africa—to join them, usually on the last afternoon, after the private dinner and the private conversation were over. Then in 1999, urged on by Canada and Germany, the G8 instituted the G-20, an assembly of finance ministers and central bank governors accountable for the newly relevant economies. Last year’s global financial meltdown finally forced members of the G8 (happily or not) to hand over responsibility for managing the world’s economy to a new G-20 of principal leaders.

These twenty represent about 85 percent of the world’s gross national product. They are located in the North and the South, the East and the West; they are lenders and borrowers, debtors and creditors, exporters and importers, manufacturing and service economies, innovators and adapters. In short, they mirror the global economy. None of the challenges the world faces coming out of the crisis—financial regulation, monitoring financial risk, reining in the cowboys—could conceivably be tackled without them. The question is whether we can do it with them.

For a timely lesson on the perils of supersizing, we might look to Copenhagen. Here was a UN-led event that included everyone—states, NGOs, and private sector companies with an interest in environmental legislation. Logistics were a nightmare: delegations could not get all their members into the convention hall, observers jammed the corridors, leaders could not find their briefers. But it wasn’t primarily the physical crush that damned the outcome. The important countries were simply too divided to achieve consensus.

When Barack Obama finally arrived at the Bella Center, on the second-last day of the conference, his secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, warned him that this was the worst meeting she had attended since “eighth-grade student council.” India, China, Brazil, and South Africa were meeting separately from the established powers; they did not see global warming as a “homemade” problem, and strongly opposed any binding targets without adequate compensation from early polluters. Chinese staffers tried to delay President Obama’s meeting with Premier Wen Jiabao and friends, and Clinton had to push her way through, followed by the president. But it was too late. All the group managed to agree on was a general statement of principles with no binding targets.

Copenhagen made it clear that direct democracy at the global level is unmanageable. At the same time, an oligarchy of eight is no longer an acceptable platform for a new global bargain. Enter the G-20: not too big, not too small… hopefully, just right. Of course, even if the G-20 can manage some early successes, it’s not out of the woods. So as we watch the limos glide through Toronto this June with their blinds drawn, the future unknown, it bears remembering that even fairy-tale endings can be brutal.

This appeared in the June 2010 issue.