Peter MacKay wants you to know that he’s happy to live in a country that has grown more accepting, more tolerant, and more understanding of the LGBTQ community, especially “in a world where sexual orientation and gender identity are still used by tyrants and bigots to belittle and oppress.” Even if Canada is better than most, MacKay insisted in a campaign statement, “there is still more work to be done.”

Well, at least that was MacKay’s position in January, when he was the presumptive front-runner in the Conservative Party of Canada leadership race. In late April, feeling pressure from his competitors, MacKay decided it was time to belittle people based on their gender identity. In a campaign missive sent off to supporters, MacKay politely chided Erin O’Toole, his main competitor in the race. “He’s been a good friend in the past,” MacKay wrote. “Someone I supported and worked with. While I haven’t always agreed with him, like when he voted in favour of the Transgender Rights ‘bathroom’ Bill in 2012, I’ve always respected that his motivations were positive.”

Anyone who followed the more than decade-long debate over that bill recognizes that transphobic slur for what it is. Bill C-16 extended the Canadian Human Rights Act to forbid discrimination based on gender identity and gender expression and gave judges the power to impose higher sentences for crimes motivated by hatred against gender identity or expression. These protections are identical to the ones that already exist for a list of other classes, including sexual orientation and race. These protections have been law since they were passed, under Bill C-16, in 2017.

Despite that, MacKay is rewinding back to when he voted against a similar bill in 2013—back when opponents of the bill baselessly alleged that it would be used by sexual predators to target girls in bathrooms across the land. It was transphobic then, and it hasn’t aged well. It was, at best, a suggestion that any trans person on the street could be a predator in disguise; at worst, it was a suggestion that trans people are inherently predators.

After the email sparked backlash, MacKay’s team quickly worked to walk back the attack. “Mr. MacKay’s views have evolved,” his campaign said, adding that “he would have voted in favour of Bill C-16, alongside many Conservatives, to protect transgender Canadians.” The statement acknowledges that the term “bathroom bill” “is narrow and carries a negative connotation.”

But the statement couldn’t quite explain why MacKay’s campaign thought it wise to signal a difference between their candidate and O’Toole. A staffer at MacKay headquarters said the email was meant to show that O’Toole and MacKay were actually of the same mind on LGBTQ issues, but the phrasing was just “sloppy.” That Jedi mind trick doesn’t quite address the thrust of the email—which was posted to Facebook by an unhappy recipient the morning after.

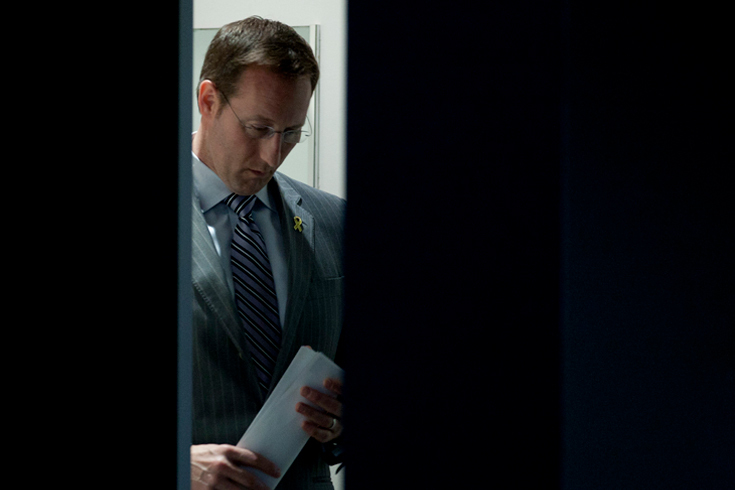

From afar, it looks bewildering. MacKay has positioned himself as an affable centrist. Once leader of the moribund Progressive Conservative Party, in 2003, then a high-ranking minister under former prime minister Stephen Harper, MacKay has been the odds-on favourite to replace Andrew Scheer as leader of the Conservative Party of Canada. Polls of Conservative voters put him in the lead, and he has racked up a list of endorsements from within the party. Ex-Harper-apparatchik Tom Flanagan recently wrote in the Globe and Mail that MacKay “is well positioned to attract the suburban Ontario voters that the previous CPC leader had difficulty reaching.”

In recent weeks, however, as the Tory leadership contest has been sidelined by the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems excitement for MacKay may have waned. While MacKay’s campaign brought in more money, O’Toole’s had nearly a quarter more individual donors. In fact, when combined, more donors contributed to the two more socially-conservative-minded candidates—Derek Sloan and Leslyn Lewis—than to MacKay. It would be easy to conclude that MacKay’s transphobic pivot is just a political calculation. But a closer look at his political history suggests the larger story of a politician who has never been terribly moored by a concern for human rights.

MacKay has a history of pursuing policies that work better as bumper stickers than as legislation—a habit that has put him at odds with the courts time and time again. He was Canada’s justice minister and attorney general for two years, from 2013 to 2015, and in that time, a raft of bills was rammed through the House of Commons—either introduced by him or by the then minister of public safety—that would mire Ottawa in round after round of costly litigation. And MacKay’s legislation would, almost without fail, lose those challenges. As he now vies for the Conservative leadership after four years on political hiatus while working in his private legal practice, it’s tough to pick a moment that best encapsulates MacKay’s checkered tenure as minister of justice.

Was it the antiterrorism Bill C-51, which greatly expanded criminal prohibitions around terrorism and gave Canada’s spy agencies unprecedented new surveillance powers, sparking widespread opposition from civil-liberty and privacy advocates? Constitutional challenges to that law were never heard as the Trudeau government quickly repealed large parts of it after coming to power.

Or was it his defence of requiring offenders to pay a sort of crime tax—a “mandatory victims’ surcharge”? Judges across the country refused to implement sections of that bill, with one calling it a “tax on broken souls.” The surcharge raised millions of dollars and was meant to fund victim services in provinces. If offenders couldn’t afford it, Ottawa insisted they work off the debt. The problem was that some provinces either didn’t have fine-repayment programs or had programs incompatible with how the federal law was written. The surcharge was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2018.

Perhaps it was the prostitution law, Bill C-36, which criminalized the sex trade. MacKay’s bill, written in response to a Supreme Court ruling striking down Canada’s existing laws around prostitution, attempted to criminalize the purchasing of sex as well as to introduce a slew of restrictions on advertising sexual services. In February, an Ontario court found provisions of the bill unconstitutional. (That case is now likely to make it to the Supreme Court.)

Or maybe it’s the bill supposedly written to combat cyberbullying, Bill C-13. That bill enshrined the ability of cops, spies, and a host of others to access, without a warrant, Canadians’ personal information from cellphone and internet service providers. Police searches of internet-subscriber information were declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court while the bill was still being debated, meaning those provisions were largely dead on arrival.

There are, in fact, scant few examples from MacKay’s time as justice minister you can point to as being unmitigated successes. When we track each major piece of legislation drafted or implemented by MacKay—from introduction to committee to the eventual constitutional challenge against it—what becomes clear is that MacKay doesn’t appear to think very highly of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms or, at least, of how it’s been applied by the courts over the past few decades. The Supreme Court has taken a more bullish approach to how Section 7, in particular, (which protects life, liberty, and security of the person, in case you’ve not memorized the Charter) can be applied to protect safe-consumption sites, legalize the right to die, and do away with overly harsh mandatory minimum sentences. But MacKay, as attorney general, seemed to front a philosophy that argued Ottawa should get to decide where our constitutional rights begin and end. The courts, in his world, are interpreters of the will of government, not vanguards of our civil liberties.

We know, thanks to a whistleblower, that MacKay’s justice department was notorious for introducing legislation that it knew would almost certainly be ruled unconstitutional. It told government lawyers to flag bills only if “no credible argument exist[ed] in support of it.” In fact, that whistleblower, the former general counsel for Justice Canada’s legislative branch, revealed that the Harper government—under a set of policies that continued under MacKay—would table legislation even if it had just a 1 percent chance of surviving a legal challenge.

MacKay now wants to trade on that experience to become prime minister. It’s hard not to have concerns.

MacKay declined an interview for this story. Not surprising, as he has had little love for the media while on the job. His office was notorious for not giving the press details on new legislation until he was already standing at a podium announcing new measures. When journalists started asking about provisions tucked in the back of Bill C-13—the one that would allow for warrantless access to Canadians’ data—MacKay sidestepped the questions and walked away.

In an email statement, MacKay told The Walrus that “the reforms enacted during my time as Minister of Justice were intended to re-balance our justice system to ensure greater accountability for offenders and to give victims the compassion and help that they deserve.” He further defended C-13, arguing “I have no regrets about any efforts to protect Canadians from convicted killers or the harm caused by cyber bullying.”

Publicly, MacKay has projected confidence over his flawed legacy. “While I was the Minister of Justice I worked hard to make sure dangerous criminals were behind bars,” he recently tweeted. “I worked to end parole for life sentences, and protect victims with the first ever Victims Bill of Rights. There’s more where that came from.” What struck me as most odd about that message was the photo attached to it, a blown-up quote referring to MacKay as the “tough-on-crime architect.” When I saw that phrase, I thought it looked familiar—then I realized I’d written it in the headline of a 2015 Vice News article. It hadn’t been a compliment.

MacKay also doubled down on his record in an interview with the Globe and Mail, telling the paper, “I will never apologize for having stood up for victims. And I think that the victim surcharge would and could and should work well for Canadians.” In so doing, he conveniently sidestepped the fact that the only reason the law isn’t working for victims the way he intended is because the bill was written in such a shoddy manner. MacKay, it’s true, wasn’t justice minister when the bill was first introduced; he was the one tasked with implementing and defending it. But deficiencies in the bill could have been ironed out in a number of ways—by directing federal Crown prosecutors to not push the surcharge, say, or simply by not threatening judges who refused to enforce it (which MacKay did). For failing to address the issues later exposed by the Supreme Court, MacKay bears much of the responsibility.

In his email statement, MacKay says he still believes that a mandatory surcharge is the best way to fund services for victims, and further added that he disagreed with the majority of the Supreme Court, which declared the fine unconstitutional. He did, however, suggest that he would explore enforcing the surcharge, were he to become prime minister, and that he would be interested in “further pursuing the fine options programs in some provinces that would allow offenders to do community work if they are unable to pay the surcharge”—something he probably should have done when the bill was first being debated.

And that failure is what many of these files have in common. While MacKay can and likely will pretend that the Supreme Court of Canada is an enemy of his common-sense approach, it’s worth remembering that he was the enemy of his own agenda. The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights actually tied together an array of really sensible policies aimed at helping victims of crime and their families, and the surcharge was meant to fund those supports—but the total lack of thought on that front jeopardized the whole laudable plan. The antiterrorism Bill C-51 modernized the Criminal Code in necessary ways, for example by allowing the courts to issue peace bonds for terror suspects—but it was written with such broad strokes, like giving CSIS incredibly wide latitude to act without a warrant, that it threatened to turn our security agencies into unchained behemoths.

And that’s at the core of what made MacKay such a problematic justice minister—he appeared to see the legislature as a cudgel to punish all manner of perceived wrongdoing. In the laws introduced by his government, there was apparently no ill that couldn’t be prosecuted, investigated, spied upon, or policed.

Alternatively, MacKay could try to forge a new path ahead while recognizing where he failed in the past. There is political wisdom in admitting one’s mistakes—if done right. Barack Obama’s earnest turnaround on the question of gay marriage mirrored many Americans’ own changes of heart, while Michael Bloomberg’s mea culpa on his racist carding policy felt calculated and disingenuous. MacKay’s legal blunders are no less serious. Sex workers continue to be targets for violence as the law continues to push their profession into the shadows. The overincarceration of Canadians, especially of Indigenous people accused of nonviolent offences, continues to be a costly and inhumane disaster.

If the Conservative Party is going to appeal to the whole country, it’s going to have to figure out how to do “tough on crime” in a humane way. Nobody wants to see dangerous criminals walk the streets. Everybody wants the victims of crime to have the support they need. Our laws do need to evolve in order to enable police to solve crimes. But none of that would be helped by a leader who has never been able to accept that the government must be constrained by its constitution. And it certainly wouldn’t be helped by a leader whose actual beliefs, whatever earnest commitments to public service he may have, are moving targets.