Few hypothetical scenarios are harder to imagine than a conversation between Theodor Adorno and Natalie Portman. Adorno was the highbrow’s highbrow, the sage Thomas Mann turned to for advice while writing Doctor Faustus, the friend and long-time correspondent of Walter Benjamin, the champion of astringent creators like Arnold Schoenberg, the relentless foe of jazz and Hollywood, the mercilessly pessimistic Marxist critic of modernity whose “negative dialectic” has enriched thousands of scholarly studies. Portman is perhaps best known for her turn as Queen Padmé Amidala in the more mediocre of the two Star Wars trilogies.

Yet on the subject of the Holocaust, Adorno and Portman, both of Jewish heritage, might have found some common ground. In a typically dense 1949 essay titled “Cultural Criticism and Society,” Adorno—a refugee from Nazi Germany who had lost the world of his youth to the Nazi genocide—bluntly declared that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” Arguably, Portman is not as deep a thinker as Adorno (who died in 1969, twelve years before the actress was born), but the starlet has been impressively educated at Harvard and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Interviewed by the Daily Mail earlier this year, she complained, “I get like twenty Holocaust scripts a month, but I hate the genre.”

Despite their shared discomfort with Holocaust art, an enormous historical and cultural gulf separates Adorno’s statement from Portman’s. When Adorno was writing, the murder of the European Jews was so fresh that there wasn’t even a proper term to describe it. The catch-all name “the Holocaust” hadn’t yet gained the currency it would receive in the 1970s, “Shoah” was largely confined to Hebrew speakers, and the word “genocide” (coined in 1944) still carried with it the awkwardness of a neologism. In lieu of such terms, commentators most often relied on the infamous and very specific names of the camps: Auschwitz, Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, and many more. In the Portman era, not only is the Holocaust easier to talk about because it has been named; it has even become a genre, like the romantic comedy, the superhero film, or the road movie. As the saying goes, there’s no business like Shoah business.

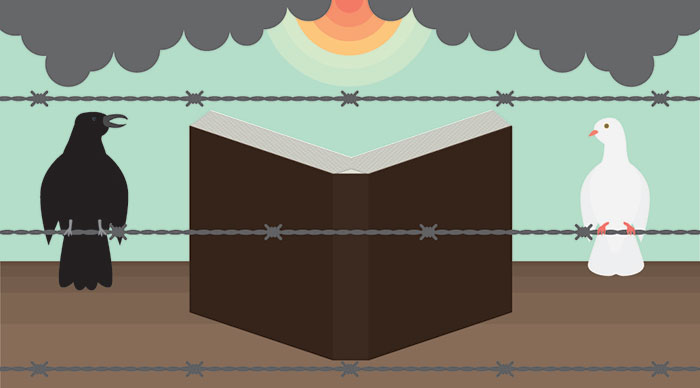

Adorno’s brief, barbed, bitter comment—more a cry from the heart than a reasoned statement—is the single most quoted sentence in debates about Holocaust art. And Adorno himself is the inevitable jumping-off point for discussion, because he pinpointed the root dilemma every intelligent artist and critic has experienced: how can you make art about atrocities? Art, no matter how difficult and painful, always involves the aestheticization of reality; every artist is a mortician who prettifies the corpse so the public can look at it without the nausea and dread that death induces. Or, as Adorno said on another occasion, “The so-called artistic rendering of the naked physical pain of those who were beaten down with rifle butts contains, however distantly, the possibility that pleasure can be squeezed from it.” In the face of the enormity of what actually happened at Auschwitz, isn’t it better for art to maintain a dignified silence?

If Portman is right and the Holocaust is now a genre, we have to say that Adorno’s worst fear has come true. Not only did poetry persist after Auschwitz, but poetry and the other narrative arts have conspired to make the Holocaust banal. It sometimes seems as if the Holocaust is for modern art what the Crucifixion was to medieval and Renaissance art: a common frame of reference and the quickest way to affect your audience. It would take the entirety of this article to list just the most famous novels, films, comics, and plays about the Holocaust: The Diary of Anne Frank; If Not Now, When?; Sophie’s Choice; See Under: Love; Maus: A Survivor’s Tale; Schindler’s List; Life Is Beautiful; The Pianist; The Shawl; The Reader. Adorno’s strictures are hard to follow. Even Natalie Portman once played Anne Frank on Broadway.

Some of these are brilliant works of art; others are unspeakably exploitive, especially that mawkish monstrosity Life Is Beautiful. But whatever quality they possess, they all must answer to Adorno’s piercing question: after what actually happened, how can you presume to offer up a distillation of reality that is also, inevitably, a distortion of reality?

Imust confess that when I heard that Yann Martel’s new novel is about the Holocaust my heart, already Grinchily small, shrank just a little bit more. “Does the world really need another Holocaust novel? ” I wondered. “Especially one written by a very goyish Canadian? ” Upon reading the book, I realized that my misgivings were somewhat misplaced. Whatever other faults Martel has, he’s not a sensation-monger or a cheap writer. His book is at worst a noble failure, a sincere attempt to write about a large and terrible subject in a fresh way, so the pain of the past doesn’t recede into history. Interestingly, he takes up the Adorno question and puts it in the foreground. Beatrice and Virgil is not so much about the Holocaust directly as it is about the problem of representing the Holocaust in art. It’s a meta–Holocaust novel, and as such more valuable for the reflections it provokes than for any literary merit it may posses.

As in Martel’s previous book, the best-selling Life of Pi, Beatrice and Virgil opens with a writer at a literary crossroads. Henry’s previous novel was an international bestseller that featured “wild animals.” As a follow-up, he writes an avant-garde Holocaust story fused with an essay on the same subject to form a flip book. Henry’s experimentalism is based on the argument that literature about the Shoah has been tyrannized by the dominance of one mode: “historical realism.” Henry’s editors aren’t happy with what they see as his notion that “we’re supposed to throw our whole imagination at the Holocaust [and write] Holocaust westerns, Holocaust science fictions, Holocaust Jamaican bobsled team comedies.”

Rejected and dejected, Henry forswears the literary life and tries to sink back into anonymity by moving with his wife, Sarah, to an unnamed foreign city. There he encounters a fan and namesake, Henry the taxidermist, who wants novelist Henry’s help with an experimental play about two talking animals, Virgil the monkey and Beatrice the donkey. The erstwhile writer forms an uneasy collaboration with the taxidermist, and both grapple with the issue that began the book, “representations of the Holocaust.” Much of the novel consists of excerpts from the embryonic play the two Henrys work on. The two animals are paralleled by stuffed specimens in the taxidermist’s workshop, and by a dog and a cat in the writer’s home; doppelgangers abound.

This literary house of mirrors contains more rooms. Throughout the book, Martel carefully tries to preclude criticism by anticipating it. Many of the tart observations one could make about Beatrice and Virgil are voiced by characters within it, notably by Henry’s editors, and by his wife, who dismisses the play-within-a-novel as “Winnie the Pooh meets the Holocaust.”

Any bald-faced summary of Beatrice and Virgil will make it sound odd. But some of the book’s strangeness disappears if we see it not as an isolated mutation but rather as an outgrowth of the fecund field of Holocaust literature. Fiction about the Holocaust has proliferated to such an extent that literary critics have found it necessary, rather like zoologists in a particularly overpopulated rainforest, to start sorting out subspecies. In his helpful taxonomic study The Holocaust Novel (2005), Efraim Sicher offers the following groupings: survivors (notably Aharon Appelfeld, Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel); the Jewish American post-Holocaust novel (Saul Bellow, Cynthia Ozick); historical Holocaust novels (Thomas Keneally, William Styron, D. M. Thomas); second-generation Holocaust fiction (David Grossman, Art Spiegelman); and postmodernist Holocaust fiction (Martin Amis, Don DeLillo).

Martel clearly belongs in the postmodernist camp, although for all his storytelling gamesmanship he lacks the intellectual intensity and verbal firepower of the great postmodernists, like Thomas Pynchon, John Barth, Robert Coover, or Leon Rooke. Rather like Kurt Vonnegut, Martel is a populist postmodernist, a middlebrow magician whose sleight-of-hand tricks are entertaining diversions rather than deep-reaching challenges to conventional storytelling. Martel is a fabulist who’s also an easy airport read, which perhaps explains his great popularity. As a writer, he is like one of those steroid-enhanced baseball players—say, Barry Bonds or Mark McGwire—who are impressively well developed in certain specialized body parts but not otherwise healthy, indeed even weak and impotent at times. He’s very talented at description, as can be seen in a long passage where two characters talk about a pear for several pages and make you look on a familiar fruit with fresh eyes. Yet he has no skill for dialogue: all his characters, human and animal alike, talk with the same monotonous, expository suaveness as the narrator’s. His forays into postmodern mythmaking add to the general unreality of his fiction.

The dangers postmodernism presents to historical reality need to be weighed against the possibility that it offers a promising solution to the problem of representing the Holocaust. The hallmark of postmodernism is a refusal to deal with subjects directly, and a preference for circumlocution, subterfuge, and the sideways glance. Postmodernism has led to a flourishing of techniques like allegory, which allows the artist to deal with serious subjects without succumbing to the burdening weightiness of documentary realism.

Martel naturally turns to allegory as his preferred narrative technique. In one of his many acts of self-exegesis, he has a character refer to the idea of “the Holocaust as allegory” to explain the taxidermist’s anthropomorphic play. This is a shrewd connection: allegory has always been the lingua franca of oppression. We know very little about Aesop, but legend holds that the fable writer was a slave. In more recent times, African American slave culture was rich in trickster tales about clever animals like the rabbit who outwits his foxy enemy. These animal tales are the forerunner not just to the stories of Brer Rabbit, but also to George Herriman’s Krazy Kat comic strip (1910–1944). A light-skinned African American, Herriman passed for white and used his cat and mouse characters to comment, subversively and slyly, on race relations. He inspired everyone from Walt Disney to Art Spiegelman, whose graphic Holocaust family history, Maus, also uses talking animals as symbols of a desperate human situation. As a work of art, Beatrice and Virgil pales in comparison to Maus or Krazy Kat, but it belongs to the same venerable and honourable tradition. Allegory’s popularity in the wake of modern totalitarianism is no accident: Ernst Junger’s On the Marble Cliffs, Camus’s The Plague, and Orwell’s Animal Farm are all early examples of artists turning to allegory as a way of writing about large public issues without resorting to journalistic clichés.

Perhaps this is precisely why postmodernism is a major mode of Holocaust literature. “In ancient mythologies and religions there are things and beings that are not to be named,” Irving Howe noted in “Writing and the Holocaust,” a 1986 essay. “They may be the supremely good or supremely bad, but for mortals they are the unutterable, since there is felt to be a limit to what man may see or dare, certainly to what he may meet. Perseus would turn to stone if he were to look directly at the serpent-headed Medusa, though he would be safe if he looked at her only through a reflection in a mirror or a shield.” Postmodern trickery and allegory are like the shield of Perseus: they allow the artist to approach the Medusa that is the Holocaust without looking directly at the monster.

Like the most annoying member of a graduate seminar or a book club, Martel likes to make great displays of his erudition. He’s careful to spell out all his precursors, so we don’t miss the fact that the original Beatrice and Virgil are from Dante’s Inferno, or that an allusion to “Birnam Wood moving to Dunsinane Castle” comes from Macbeth. He name-drops Spiegelman, along with many other Holocaust artists, just so the reader knows he understands the serious tradition within which he’s working. Samuel Beckett is also checklisted, and this is particularly important: Beckett is, in a sense, the presiding spirit of Beatrice and Virgil. Like Waiting for Godot, the play within Beatrice and Virgil is mostly focused on two characters set against a denuded, abstract background who talk around an ominous subject without ever blurting out what is scaring them.

As it happens, Beckett was one of the few modern writers Theodor Adorno approved of. Beckett is not usually thought of as a Holocaust writer, but a few biographical facts are illuminating: normally apolitical, he was angered enough by the Nazis to join the French resistance, and he had friends who were tortured and killed by the Gestapo. As scholar Hugh Kenner has suggested, much of Beckett’s work makes sense if we see it as a veiled allegory about Vichy France. “Waiting for Godot is very nearly a fable of the occupation,” Kenner wrote in a 1986 essay. “In Play three people are led over the same story again and again, under spotlights. The Gestapo grillers reputedly made much use of such lights… [Seeing] a Beckett play, reading a Beckett text, no one thinks, ‘The Occupation!’ The ‘power of the text to claw’… arises from his way of unhooking it from historical particulars, leaving something as vivid as a bad oppressive, as inescapable.” So perhaps Beckett offers one solution for the problem of how the Holocaust can be represented without dishonouring the memory of the dead, by writing allegories so oblique that they capture horror without trying to glibly explain it or offering reassuring narrative comforts.

Beckett and Martel both universalize the Holocaust, but in diverging ways and to different effects. Martel’s universalization is selective: Jewish voices are erased, as is the specificity of the Jewish experience—even the animals aren’t quite kosher—but we still get the story of Nazi evil. Beckett’s universalization was more extreme: everything historically specific is erased, and the Holocaust is unnamed. In its place, we get pure stories about torture, with characters reduced to the fundamental categories of victim and abuser. Because Martel’s universalization is selective, it produces a lopsided effect, something Beckett’s more radical art avoids.

While Adorno’s famous admonishment about Auschwitz and poetry is often quoted, many commentators forget that late in life the philosopher had a slight change of mind. In his 1966 book Negative Dialectics, Adorno wrote, “Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as a tortured man has to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems.” The contradictory statements spring from the same unsolvable dilemma: it is impossible to write about the Holocaust, but it is also imperative that we continue to write about the Holocaust. Samuel Beckett is not normally someone to turn to for advice, but there is wisdom in his great injunction from Worstward Ho (1983): “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

This appeared in the June 2010 issue.