Nineteen months ago, just prior to the onset of the pandemic, the state of internet connectivity in rural Flin Flon, Manitoba, was relatively bleak. According to the city’s mayor, Cal Huntley, it wasn’t uncommon for residents to have to drive hours south in forty-below temperatures for minutes-long doctor’s appointments and business meetings, and the town’s existing internet network was so slow that speeds would get spotty a mere kilometre out from downtown. Doorstep saviours like meal-delivery kits and impulse Amazon buys seemed like nice ideas but weren’t remotely feasible. It wasn’t until after Shaw Communications was able to negotiate access to existing fibre in the area and wire up high-speed fibre infrastructure—following Flin Flon’s “very, very, very hard” decade-long lobbying campaign—that the situation began to change. As Huntley says, “We no longer have to risk human life to do business.”

The idea of the internet as a lifeline is perhaps more literal than ever, especially in the overarching cultural context of COVID-19. The issue of who participates in the digital economy, and who can afford to, has never been more pressing—and with good reason. Connecting rural communities, like Flin Flon, has historically been a slow, costly, and cumbersome process. Currently, only around 45 percent of Canadian rural households meet the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission’s (CRTC) benchmarks of access to broadband speeds of at least fifty megabits per second (Mbps) for downloads, ten Mbps for uploads, and access to unlimited data.

Set against the backdrop of an evolving economy that is increasingly digital, the network-building companies continue to be tasked with developing the infrastructure needed to connect rural-dwellers and businesses, all while keeping up with the seemingly insatiable need for speed and performance throughout the country as a whole.

The Power of a Connection

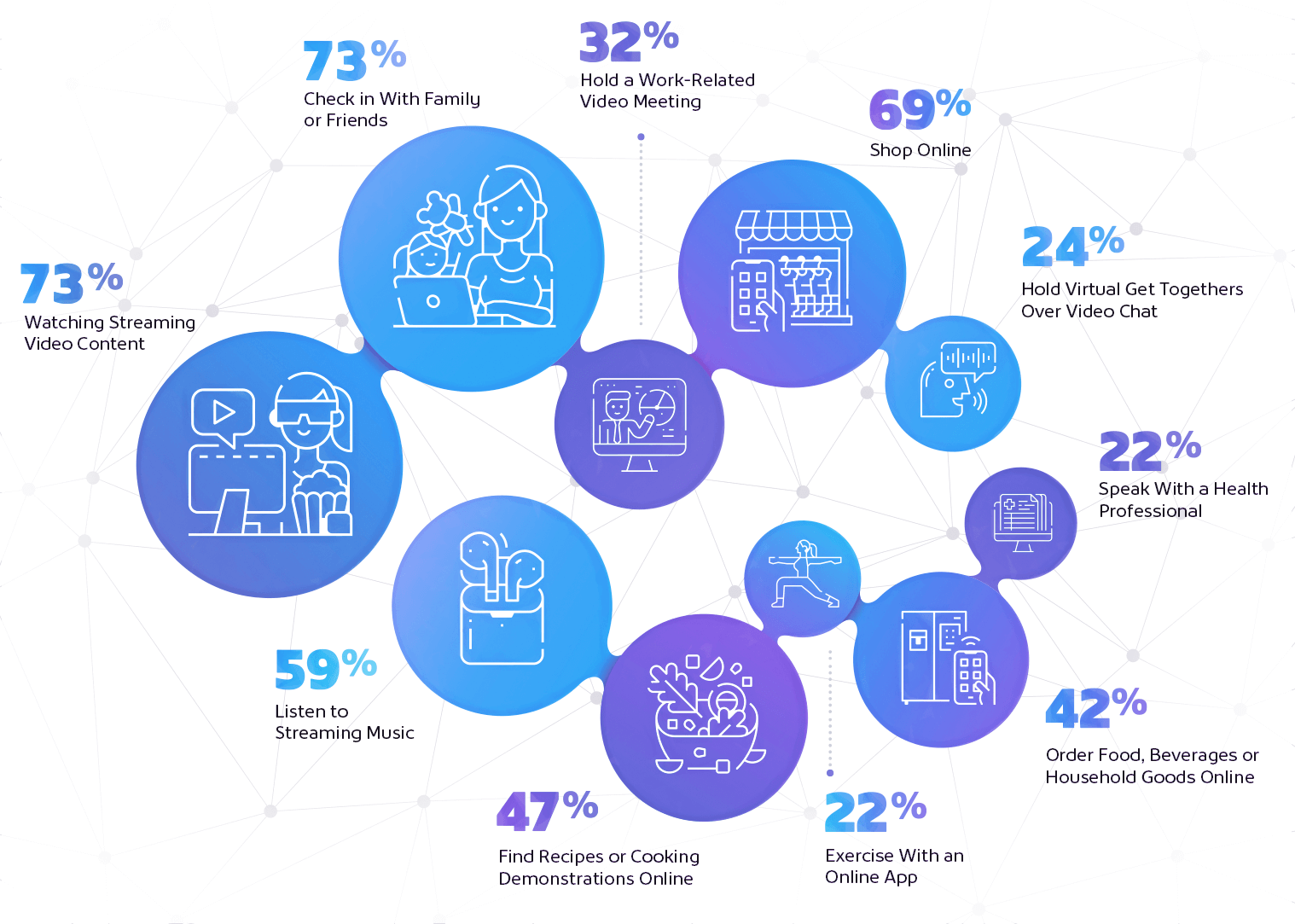

The percentage of Canadians who use the internet to do the following regularly or occasionally

Millions more Canadians have used the internet to speak with a health professional, exercise at home that requires a connection, order food, beverages, or household goods online for delivery, and listen to music through a streaming service than a year ago. Figures provided by Abacus Data

So what exactly does it take to install and maintain the millions of kilometres of ground fibre, thousands of towers, and tens-of-thousands of pieces of electronic equipment that facilitate our never-ending video conferences with friends, family, and co-workers? In Canada, it takes a lot.

Damian Poltz, Senior Vice President of Wireline Technology and Strategy at Shaw Communications, echoes a common complaint about construction in our large, frigid nation— mainly that our summer is approximately three months long. “You can’t build once the ground is frozen,” he says. Extending Shaw’s reach into underserved communities means contending with the realities of rural geography: single-lane roads, precarious mountain passes, train-only entrances, and temperatures plummeting to forty below. For Shaw, facing these realities is a very expensive task and has a direct impact on the services the internet provider is able to offer customers. “I have conversations with friends where they say, ‘In the US and overseas, you can get this-or-that plan for five bucks,’” Poltz says with a smile. “And I always remind them that the geography and population density is very different there.”

With the ever-looming threat of climate change, Tracy Johnson, Shaw’s Senior Vice President of Networks and Supply Chain, now has to factor in the possibility of environmental anomalies when planning for Shaw network upgrades. “The forest fires in BC are a great example,” she says. “They come through and wipe out portions of our aerial lines so our communications cables need to be replaced. We’re also seeing dramatic increases in our utility costs due to extreme temperatures. So, to make sure things stay running with generators and additional cooling, we require significant planning and creativity, because people are counting on us.”

Unforgiving weather scenarios aside, the average installation process of Shaw’s Fibre+ facilities is no cakewalk. Johnson describes it as a “continuous upgrade” needed to meet the growing need for bandwidth and faster speed, while avoiding frustrating network outages. Network upgrades or relocates in dense metropolitan areas, like Shaw’s recent network relocate in Calgary’s Bowness neighbourhood, constitute what the telecom industry calls a “brownfield” build, wherein community reinvigoration efforts or redevelopments — like sidewalk expansion, overall beautification, or residential infills — require service providers like Shaw to relocate their existing lines from utility poles to underground cabling. “There’s a tremendous amount of civil construction costs—up to $1,000 per metre—for us having to dig the trenches, put in the cable, then install new access for every home and business, then handle all the remediation, like landscaping,” says Johnson. “If our existing network was running with the easement of a space that’s being expanded, we have to move it. Municipalities are always growing and improving their infrastructure, and as an internet service provider, we have to ensure we’re improving alongside them.”

High-Speed Opinions

92% of Canadians said that high-speed internet would be essential or somewhat essential for them to consider living in a rural area.

84% of Canadians say their home internet network has performed well under the additional demand during the pandemic.

64% think the federal government should focus policy on quality and speed.

3 in 4 Canadians agree that having reliable high-speed internet has become essential in their life.

By a 2 to 1 margin, Canadians believe the Government should focus on making sure that the quality and speed of the internet networks in Canada are as good as possible, even if it means prices stay about where they are now.

Public opinion research provided by Abacus Data

“Greenfield” initiatives—the term used to describe network expansion into brand-new suburban developments on the periphery of major cities like Edmonton or Vancouver—come with a different, albeit hefty price tag. Though they’re in closer proximity to the existing networks, costs can hit $3,000 per home–not to mention the costs (in the hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars) of the two-to-five kilometres of network construction to distribute network fibre out to these new communities. “We also have to work with the provincial governments, municipalities, and private landowners to secure the rights and access to do those kinds of things,” Johnson says.

In highly remote areas, like the Rockies or parts of the Canadian Shield, a major concern for Shaw has been sustainability to ensure the company is, as Johnson says, “doing right by the environment,” even if the environment isn’t always cooperative. “Extra costs always seem to bubble up there, too,” she says with a laugh. “You think you’re going to have no problem, and all of a sudden, there’s a boulder the size of a small house that needs to be moved.”

“The biggest misconception about the internet is that once you install the fibre and put up the tower, you’re done—that there’s no more investment after that, and we’re banking all of the money. That’s absolutely not the case,” Poltz says. When COVID-19 hit, Calgary-based Shaw had just completed a massive eight-year, $32 billion investment in infrastructure and services—an expenditure that Poltz credits with bolstering the company’s network to manage the “tsunami” of traffic it experienced during the first week and a half of lockdown (Shaw saw over two years’ worth of traffic in the first few weeks of the pandemic).

As Poltz describes it, the public’s ever-growing need for faster speeds and supporting infrastructure is never ending. Shaw’s average per-customer peak-hour internet usage has ballooned by 13,314 percent since 2003, with an average year-over-year increase hovering around 40 percent. This stark and continuous increase requires Shaw to constantly invest in upgrading its network equipment. “Imagine using twenty-, ten-, or even five-year-old technology? It just wouldn’t work to support the capacities that we need,” says Poltz. “We’re now offering multi-gigabits per second, and with the rise of remote work and schooling, COVID has only accelerated things.”

Ben Dachis, Director of Public Affairs at the C.D. Howe Institute, and a key player in the firm’s recent telecom-policy working group, underscores the need for regulatory consistency when it comes to who’s footing the bill for internet infrastructure to ensure that fast, strong networks continue to be built and maintained.

This need to support network builders’ abilities to operate and invest in growing their networks is at the heart of a decision passed down by the CRTC—the body charged with regulating internet access—in May 2021. This decision saw the reversal of a 2019 ruling that would have significantly undermined investment in Canada’s network infrastructure. Fortunately, the CRTC fixed these errors in their 2021 ruling, giving network builders the confidence to keep investing in higher speeds and bringing connectivity to more Canadians.

“We can see around the world that, when you have this kind of uncertainty, you see a pretty substantial gap in internet investment,” says Dachis. “If you apply that to Canada, we’d be looking at a couple of billions of dollars of reduced investment that would hamper 5G deployment.”

Overall, Canada ranks well in telecom investment—$255 per capita compared to the OECD average of $156—which is an indisputable reason for our fixed broadband speeds being some of the highest in the world. But that’s not a coincidence, and going forward, it will be of the utmost importance to strike a suitable balance between affordability, in-market competition, and the practical economics of building out facilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated and amplified the digital transformation taking place around us. For Shaw, facilitating connectivity in a post-COVID world has meant an irreversible shift in operations. “With everybody now working from home, we’re now doing network maintenance at night, which means organizing light generators and road closures,” Johnson says. “Between midnight and 5 a.m. is really the sweet spot.”

Despite the pandemic’s necessary triage mentality, Shaw’s overall focus has never deviated from the future. “We can’t be building a network that’s just good enough for today,” Poltz says. “It takes ten years to upgrade our network, and we invest billions of dollars per year to maintain a system for the future, so we have to be extremely forward looking: what are Canadians going to need in a decade?”

As just one example of what our digital future will look like, some of our newest internet idiosyncrasies are here to stay. Though Poltz says Shaw’s customers have more or less returned to video-streaming patterns seen before the pandemic, the company’s rates of upstream traffic have stayed consistently high since last year—a strong sign that the video-collaboration technology Canadians are using to work and learn from home, and interact with friends and loved ones, is likely here to stay. Poltz also predicts that more connected devices, new and more immersive content services, and crucially, the need for better connectivity for remote and underserved communities mean Canada’s networks will be relied upon like never before.

Simply put, the internet has grown to become the lifeblood of our economy, and is very much the driving force behind how we live, work, and interact with one another. This will only increase as time goes on. “The internet was once thought of like a luxury, but now, it’s something that’s so embedded in our lifestyles and everything we want to accomplish in humanity,” Johnson says. “Imagine not having the internet in your home over the past year. Work, schooling, connecting with family and friends—that was all made possible by investment into the network.”

In the stark before-and-after case of internet speeds in Flin Flon, Huntley underscores the mental-health implications of staying connected. “We’re going to be living with some of the repercussions of the isolation that we did experience, even with high speed, for many, many years,” he says. “But the community as a whole has changed dramatically for the better.”