TECHNOLOGY / JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2025

Hello, I’m Phoenix. Would You Like Your House Cleaned?

Get ready for an army of robots that work—and reason—like us

BY MICHAEL HARRIS

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JIMMY JEONG

Published 6:30, NOVEMBER 13, 2024

The robot has a grey and immaculate face with no mouth, no nose, and two unblinking eyes. It’s a face without human pretensions. But, like me, it has a name—Phoenix—and between that geometric resin mound and myself, there is an immediate camaraderie. The robot and I are basically the same height and weight; we both peer and bend toward each other with undeniable curiosity. When I extend a hand, Phoenix looks down, cocks its head three degrees, and considers. Then, gingerly, it places a hand in mine, and we shake.

“Nice to meet you,” I say. “That’s a good grip.”

“Thanks.”

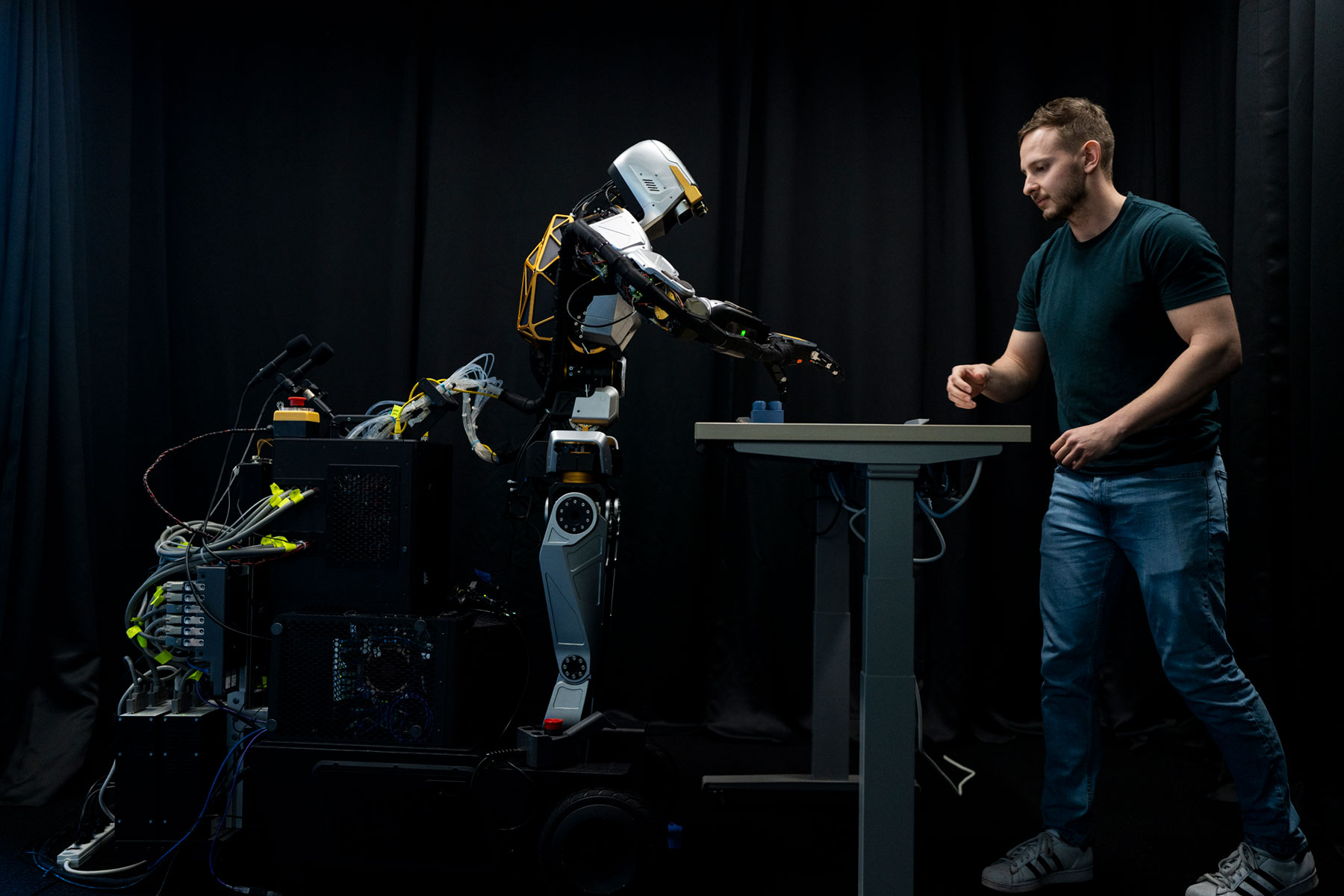

The voice isn’t the robot’s, though; it’s a human’s. I turn to look at the guy strapped into a convoluted rig behind me. Eric wears an exosuit complete with a virtual reality headset and wire-spewing gloves that track his minutest movements, relaying them to Phoenix. Eric has his own hand outstretched, and he’s shaking empty air. He is, in fact, remotely inhabiting the robot whose hand is still in my grip. Phoenix and Eric see together, move together.

I am only beginning to grasp what this handshake foretells. If remote-controlled greetings were the robot’s whole repertoire, it would be a neat trick. But any sense of play very much misses the point. Phoenix is no puppet, no toy. And the mimicry it engages in is only a prologue to something far more profound. Phoenix is furiously—wonderfully—learning.

Built by the Vancouver company Sanctuary AI, Phoenix is racing to become the world’s first general-purpose robot with human-like intelligence—a machine capable of understanding the real world and executing tasks previously done by us. It is an embodied AI. Its intelligence does not merely flash inside a server but reaches out and acts. Like a wide-eyed toddler, it gains facility as it explores and practises.

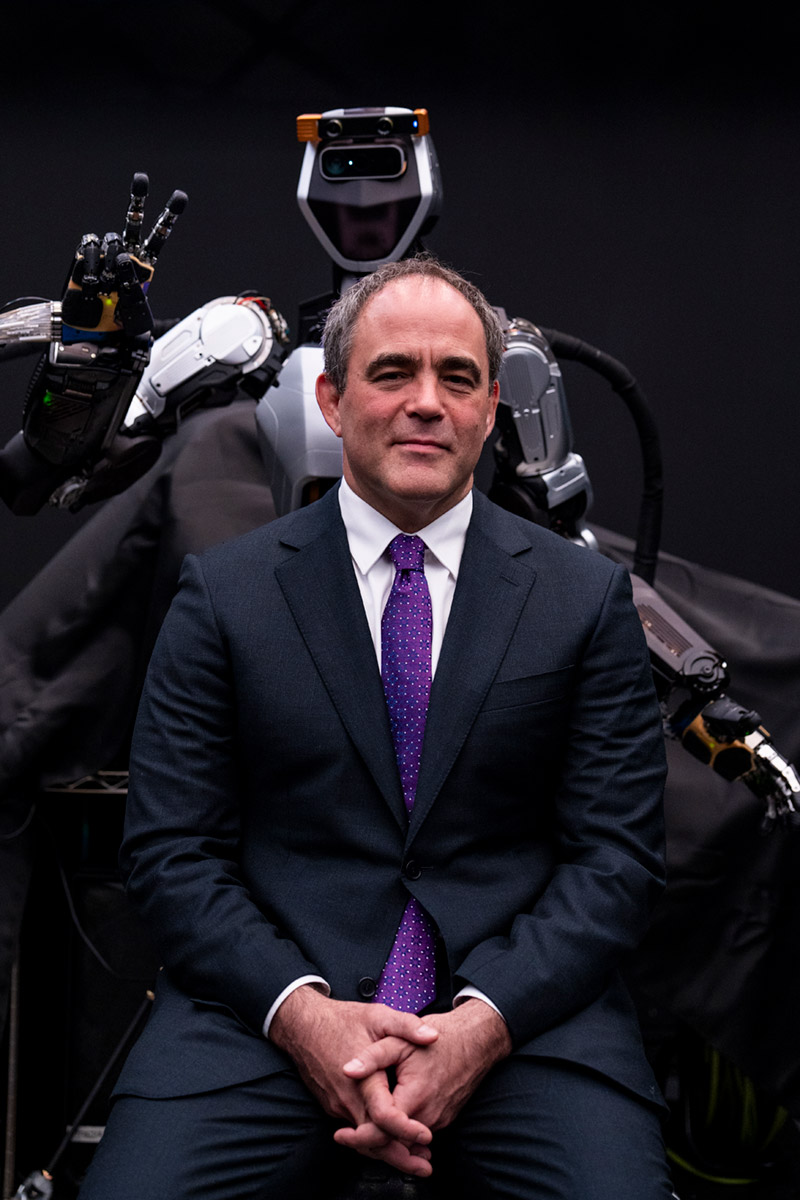

While walking the gleaming white hallways of Sanctuary, I see only a few Phoenixes on hand. (Sanctuary is coy about the total number it has built so far.) I ask co-founder and then CEO Geordie Rose, “How many robots like Phoenix do you expect will eventually be built?”

“Billions,” he says without blinking. “A billion robots sounds like a lot, but it isn’t, not really. Because people have an unlimited desire for cheap, high-quality labour. If I can deliver that labour for, say, twenty cents an hour per robot—the price of electricity—people are going to find ways to use that labour.”

The business case for such an enormous fleet depends on basic human demographics. Global fertility rates have collapsed, while life expectancy has soared. In 2015, the proportion of those over sixty on the planet was 12 percent, but that number will nearly double by 2050, according to the World Health Organization. Meanwhile, labour shortages are reported everywhere—and more are predicted. The result, says Rose, is simple: a massive need for workers, be they human or robot.

In many cases, a clever app will not be enough to fill the labour gap; an app cannot take out the garbage, pack a box, or build a car. What could, though, are automatons capable of both understanding the space they inhabit and acting upon it. These helpers should look like us and share our shape and basic dimensions—for they’ll work in a world that’s been custom made for the human body.

Thus far, the AI revolution has largely been disembodied. The new tech arrived in an insubstantial state, a spirit behind glass. Its first products—screen-based wonders like ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini—were insubstantial too. They spin out essays or videos in response to our queries but have nothing to do with the rock and wind and dirt of the larger world. Rose and many other founders believe the next step in AI’s evolution must involve embodiment. At this year’s “We, Robot” extravaganza, Tesla CEO Elon Musk unveiled a new version of his Optimus droid, which mingled with crowds and served drinks. He called it “the biggest product ever of any kind.” This produced the kind of excitement last seen when, a few years back, Boston Dynamics released a video of its Atlas humanoids dancing to “Do You Love Me” with unheard-of finesse. Still, the race to deliver a proper general-purpose robot to the marketplace is a long one. After “We, Robot,” it became clear that the Optimuses were being remotely operated by humans—which Musk had neglected to mention. And as for the fleet-footed Atlas: I remember one robotics expert telling me that the simplest way to evade one would be to climb onto a box.

Pitfalls and limitations are all surmountable, though, in the eyes of tech visionaries. By 2030, Amazon expects to employ more robots than humans. Meanwhile, hundreds of millions of dollars in funding now flow into robot start-ups. Sanctuary itself has received over $140 million in start-up funding (including $30 million from the Canadian government). Investors include Bell, as well as Accenture and Verizon Ventures; partners include the automotive manufacturer Magna and Microsoft, whose cloud platform Azure will house a part of Phoenix’s “mind.” This is a lot of attention—Time magazine named Phoenix one of the best inventions of 2023—for a mechanoid whose only public work experience consists of trial runs at a Mark’s outlet and a Sport Chek where it packed merchandise, cleaned surfaces, and folded clothes.

Then again, as with all tech start-ups, Sanctuary’s real value lies in an unspoken promise: that a robot could, one day soon, become competent at not just this task or that task—but every task. Rose is determined to work toward that grander goal. “What we are going to do is build something that’s not a vacuum cleaner,” he says, nodding at Phoenix, “not a tote mover, not a warehouse robot. We’re going to build a human mimic.” The consequence of such a lofty aim, of course, is that Sanctuary’s end product could embody some of our greatest fears (being replaced, made redundant) along with our greatest desires (a life of leisure, infinite economic growth). These are the existential notes that hum around Sanctuary’s office.

Down another wing of Sanctuary HQ, I watch a Phoenix play with a bright-blue block that resembles a jumbo piece of Lego. The robot picks up the block and places it on a tray. A staffer then moves the block to a different part of the table, undoing Phoenix’s work and setting up a separate physical problem. Undeterred, the robot moves the block back to the tray. The two go on like this—doing and undoing the same simple task. Then I notice the glowing light at the centre of the robot’s chest. In the first room, where I had my handshake, the light shone blue. Here it’s amber. The change indicates that Phoenix is not being operated by a pilot anymore. It is working and thinking using artificial intelligence—on its own.

I look Phoenix in the eye. A deeply serene, utterly neutral expression. The block needs moving. It leans forward and takes hold of it with cautious, human-like care. There’s a simian style to these movements that is powerfully endearing. A patina of the primate.

Where’d you learn to act like that?

Before Phoenix can do anything on its own, it must first copy the actions of humans, to build a library of basic skills. It does that by monitoring people like Eric, the pilot. It’s a little like showing a child how to whisk an egg by first holding your hand over theirs. Depending on the complexity of the task and environment, Phoenix typically requires about 200 examples before it develops “muscle memory” and can execute the task on its own. Since Phoenix learned to move by studying human movement data, its gestures have a hominal quality; it has absorbed its teachers’ ticks and habits. It does not move with jerky turns and cold, steady tracking. It moves with a gentle and tentative demeanour. “They take on mannerisms,” says Rose, the word “our” hanging unsaid.

Technically, the robot has a great deal more potential than what’s on display when it handles blocks or shakes your hand. But Rose is playing the long game, building a library of elementary movement data. Each time a human pilot helps the robot pick up an object, “we get all of the information about what it’s actually like to pick up an object from the robot’s perspective: the camera feed from the robot, the microphones, the touch, the proprioception, all of it,” Rose says. That holistic understanding, complete with human idiosyncrasies, is stored and recalled whenever the robot engages in the task on its own. It’s these memories, if you will, that allow Phoenix to operate on its own with such animal care. It is mimicking the care of its human teachers.

When a disembodied AI (the kind that lives in your phone, for example) needs to learn a new skill, the parent company will scrape some corner of the internet for educational material. ChatGPT, for example, employs a large language model that’s trained to create text by studying things like Wikipedia and online books. Similarly, versions of the DALL-E image generator learned what humans want by hoovering up hundreds of millions of online images. Generative AI systems use massive data analysis to learn what word or pixel or sound is most likely to come next in a given sequence and, in this way, build a story or an image or a song piecemeal, without ever conceiving of the whole. A robot can, theoretically, do the same thing with movements. It can learn to walk or jump or sort objects into pails by analyzing a wealth of examples and then using that data about the physical world to guess what micro movement, what action, would be best to take next.

Except there’s no comparable database of movement knowledge that an embodied AI can learn from—no Wikipedia of walking or library of touch. For all the brilliance of online life, it has been a fundamentally flat experience. So as a wave of embodied AIs step into being, they’ll need new sources of data for their large behaviour models—vast new troves of information about what it means to move through space, to have a perspective, to be a self in the bewildering world and not just an invisible charge in a server.

Building such systems, though, turns out to be an extraordinary challenge. Many tasks that humans consider simplistic (walking, throwing, lifting, catching) are painfully difficult for a computer to pull off. By the same token, an AI that doesn’t have to deal with “the real world” can appear vastly more impressive. Two years before Sanctuary was founded, a Google AI program conquered the game of Go, defeating a top human player. It is easier, Rose says, to teach an AI to play Go than it is to teach a robot to move the stones on a Go playing board. This difficulty matters enormously because fine, hand-driven manipulations are required for 98.8 percent of all work, according to 2023 data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The prosaic but infinitely complex hand is where thinking meets the world. For this reason, Phoenix has been endowed with human-like touch sensitivity, and its hands have an ability to rotate, flex, abduct, adduct, and extend—just like our own.

AIs that live cozily on screens are writing academic articles, influencing the stock market, and designing new drugs, but Phoenix plays with blocks. It exists in the grasping, exploring stage of development, so it will be some time before it arrives at factories en masse. “You can’t take a baby,” says Rose, “and put ’em to work in the coal mine.”

But Phoenix is growing up fast. Every piece of data it gleans from training sessions is fed into Sanctuary’s crown jewel, an advanced AI control system called Carbon. Bit by bit, Carbon is making itself into a mind that can understand, with granular detail, what it is to have a body in the world.

Given enough training data, Phoenix could achieve what’s called zero-shot learning, the point at which training sessions are no longer necessary and Phoenix can execute any task after nothing more than a verbal command. Navigating a previously unknown workplace, for example, would require no human supervision. An unknown item could be identified by calling up auxiliary information and making an inference. Humans do zero-shot learning all the time. We execute without copious training because we have models of the world in our head and we can use those models to game things out. Rose uses basketball to explain: someone is taught to score a shot from very close to the net, and then, without further instruction, they are moved to the three-point line. “You could still hit the basket,” Rose says, “even if you’d never done it before. Because you know enough about the world to adjust your behaviour.” Similarly, a general-purpose robot should be able to execute every job, in every environment, by reasoning. “They’ll just know how to do it,” Rose says. “They’ll infer from what they already know and be able to generalize about a situation.”

The Carbon system partly resides in the body of each Phoenix, which allows for immediate feedback during physical action. But another part of Carbon resides in the cloud as a kind of shared intelligence, a wisdom depository that every Phoenix contributes to and every Phoenix can draw from. Which is another way, I suppose, of describing a culture. What, after all, is our own memetic culture but the human machine’s hack for sharing models, data sets, feedback, and experience with one another?

The longer I stayed at Sanctuary, the more I became enamoured of the robot’s presence. Far from growing used to Phoenix, I begged to be allowed more time with it; I had an animalistic wish to elicit its curiosity or to meet, again, its guiltless gaze. It was like meeting a new puppy—that visceral a connection. What kind of encounter did I imagine this was?

Once a general-purpose robot is given the power to reach out and shape the world, the big impossible questions begin to loom. How is this robot different from animals—from us? Does it have choices, preferences, desires? Is the robot sentient? Does it have a self?

It would be comforting to call these questions anthropomorphic daydreams. But that comfort begins to crumble when we consider the evolution of our own selfhood. Life on Earth, after all, did not begin with a point of view. Somewhere far down the trunk of the tree of life, a series of adaptations led to the necessity and, thus, the growth of a mind.

Billions of years ago, life likely began underwater and was, for a long time, helplessly floating (incapable of directing its own path, much less caring where it went) or stationary (fixed to hunks of rock). Then, by 550 million years ago, an early animal called Dickinsonia was able to wriggle its pancake-shaped body across the sea floor in search of food, leaving behind imprints that we can see in fossils today. It is believed that roughly around this time, and not coincidentally, nervous systems developed too. Mobility was a useful trait, after all, only when paired with the ability to sense the environment. These two adaptations eventually allowed early animals to move toward prey or away from predators.

But sensing and acting then create a knock-on innovation: learning whether you’re touching and feeling something other than yourself. Early animals were “now sensing the world in a way that tracks the divide between self and other,” writes philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith. A mobile and sensitive creature must, in other words, have some rudimentary idea of its own body. What’s more, the expansion of sensing and acting eventually requires organized strategy. “Evolution,” writes Godfrey-Smith, “puts a premium on coherent action, and from a certain point onward, the way to act effectively as a self is to have a sense of oneself . . .” Consciousness is the answer. Consciousness is the most efficient way for all that sensory data to be marshalled and put to use. Agency produces subjectivity.

And so the self isn’t a magical endowment but the inevitable consequence of having a body that can sense and act upon its environment. Not only can a sensing, acting body produce a self—many feel it’s the only feasible path. And, conversely, selfhood might forever be denied to a locked-down computer, no matter its processing power. The philosopher John Searle once explained to me that consciousness cannot be arrived at by simply computing reams of numbers. “You can’t get there by shuffling symbols,” he said. But he felt that you could get to consciousness while being a machine. “We are machines,” he told me. He likened the production of consciousness to the flying mechanics of a bird—telling me that being alive and awake to the world was that mechanistic and corporeal a process.

Rose believes artificial general intelligence without integration in a body is an incomplete concept. Calling a clever chatbot an AI is “an abuse of language, because that is not really intelligence,” he says. Could Phoenix’s embodied intelligence, then, be the start of Searle’s machine process? “Embodiment,” says Rose, “provides the context for learning and understanding abstract concepts, emotions, and the nuances of a person’s experience—which are essential parts of our intelligence.” According to Rose, “the development of selfhood in an AI would probably start with this idea of a model of the self.” That model is what Phoenix is busy building—a map of reality with itself at the centre.

What Phoenix forces us to confront, in other words, is that selfhood, or a conscious point of view, may be a tool like wings or claws or fur, something produced by the pressures of evolution. Of course, we don’t know exactly how a self comes to be—that question will remain one of the most confounding mysteries in both philosophy and practical science—but we may begin to guess at the circumstances that force the light of “I” to glow.

Contemplating a variety of types of self may feel like science fiction, but it’s not an unreasonable exercise. There are already many kinds of self on Earth. Many animals, for example, have sensory systems that differ vastly from our own and create a kind of fractured or pluralist selfhood unlike our more individualist identity. In an octopus’s body, the majority of its neurons are located in its arms, meaning each arm can act with some autonomy from its brain. One half of a dolphin’s mind sleeps at a time, the creature remaining demi-conscious so that it can come up for air. We know, too, that our sense of self warps when the brain is addled by drugs or injury. The self is not a perfect diamond that hovers at the centre of your skull but a pound of clay that takes one shape, then another.

Godfrey-Smith, in describing the subjective realities of insects and slugs, encourages us to widen our curiosity and conceive of “varieties of subjectivity.” But that puts us on a nervous footing. If we respect the distinct perspective of a hermit crab—or, say, a robot like Phoenix—then the specialness of humankind, our belief in the supremacy of our precious souls, begins to get lost in the crowd. “Often in the history of science,” says Rose, “there’s a consensus about something that’s completely wrong, and then a thread is pulled and the entire world view unravels. I suspect that the study of our conscious experience is one of those threads.” The earth is decentred and goes spinning around a random star; a child’s destiny is fractured into strands of DNA; quantum physics unmakes our material reality. The radical undoing of that which seemed rock solid is not so unlikely as we sometimes imagine.

To be clear, Sanctuary is not attempting to spawn a new race of sentient beings. And Rose does not think the unravelling he describes will happen tomorrow. Still, creating general-purpose robots comes with existential repercussions. In building machines that engage the world with precocious dexterity and care, we might endow them with wakeful qualities that disturb their creators. Where does the simulacrum end and genuine experience begin?

When I leave Sanctuary, I find myself on a windswept street not far from Vancouver’s downtown. Box stores, Starbucks, a Whole Foods. People stroll by with bags of groceries; they talk about the most recent season of RuPaul’s Drag Race; they look into windows and consider whether now is the right time to purchase an air fryer; a child is admonished for dragging her feet; a spouse is given a drifting goodbye kiss. Everyone behaves exactly like a human. They walk and talk and handle the chaotic world with casual expertise. No one notices the brilliance of their sensorium or the marvel of their body’s engineering.

They’re glorious, these humans. And yet today they are also, somehow, diminished. It is impossible, after meeting Phoenix, not to feel that the ordinary actions and daily tasks that make up the majority of our lives are somehow drained of significance, made robotic. Am I merely an algorithm? Just a biological arrangement of data doing the same tricks as Phoenix, tripping through if/then rules? And if much of my life is, in fact, robotic, then to what degree am I distinct from Phoenix and its kind?

When I watched the robot feel its way through a task—when I watched its tentative, exploring fingers—I did not, in the end, think to myself, It has a soul like mine. Rather, I thought, I am a machine like it. In the end, watching Phoenix made me question much more than my place in the labour market—it made me question my place in the grand scheme of things, the specialness of my perspective.

So, as the robot is elevated, I feel myself dragged down. Meeting in the middle, we both become “embodied intelligence,” we both become grasping bits of learning software. And “selfhood” may prove to be just a spectrum of self-noticing, a quality that does not flick on or off but, instead, appears in varying degrees and colours, depending on what’s useful, what is best suited to the task.

When the billions of Phoenixes come marching along, ready to fold our laundry, cook us dinner, nurse us, we’ll be grateful for their self-knowledge, I suppose, grateful for the practical wisdom that lets them navigate our world so well. But we may also be saddled with that eerie sense of demotion. We’ll be dragged off our pedestal and dropped in a humbler—if more curious—place among the vast tribe of sentient things. Then maybe, like baby robots, we’ll fumble again, reaching for blocks to build a bright new model of the world.