Kiddie wagons are made for carrying kids. I had plopped my son and daughter in our red pull-along hundreds of times for summer walks down to Toronto’s Ashbridges Bay Park for picnics, to other local parks, or sometimes for quick shopping trips. But they soon grew too old for the wagon; they used it to trundle toys to other kids’ houses. I used it to pick up garden plants from the local nursery in our east-end neighbourhood, or to move dirt. I almost sold it in a yard sale.

And on August 6, 2011, I used our wagon for a new purpose: to begin moving out of our family home. Coincidentally, August 6 is the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. Coincidentally, August 6 is also the first memorable date I had with the boy who would become my husband, at a 1987 screening of Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. I was a sixteen-year-old girl with a cherry red bob who loved foreign films, never drank or did drugs, and wore real 1920’s dresses over her bony figure to school dances. I’d never had a proper boyfriend. Sergei was 18 and had a British accent he’d picked up in the UK while there with his father on sabbatical. Over the next few months, I learned that he was actually of Russian descent, with a last name so rare fewer than 20 people in the world possessed it. He was funny, eccentric, and passionate about everything. He directed school shows and performed in them. When we fell in love, it was like mixing red and blue to make purple. We were together for seven years before marrying in 1994. We lived in Russia for two years, then in Chicago. We had kids in the early 2000s. By the time I decided to leave him, we’d scarcely spent one night apart in almost 25 years.

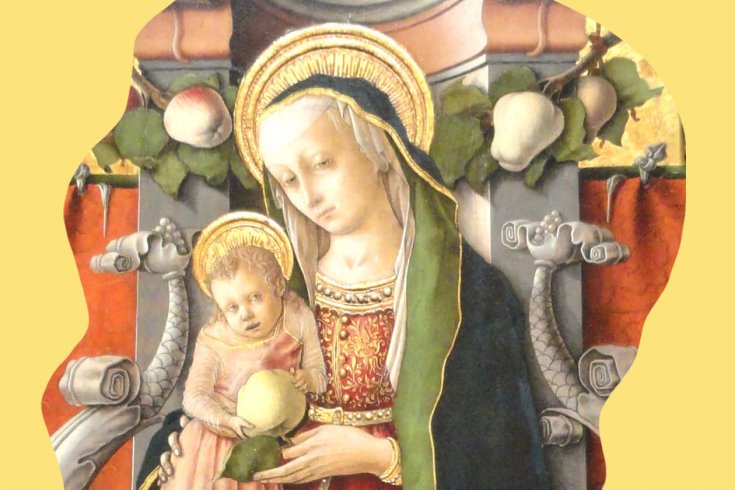

On this day, like a woman salvaging what she can from a burning building, I snatched pots and pans, a suitcase, and an icon of the Madonna and child from the corner shrine that is the heart of any Russian Orthodox household. Drinking vodka intensified the urgency. I recommend drinking as much as possible while doing something you might regret for the rest of your life. However, I don’t recommend using a kiddie wagon to make your getaway.

There was no one to observe me. My husband had taken our two children to IKEA so they wouldn’t have to witness their mother’s departure. But they knew I was leaving. My husband and I had told them the month before. I remember my son, age seven, hitting me and crying over and over, “Change your mind! Change your mind right now!” and my ten-year-old daughter weeping silently in the corner of the sofa. But they didn’t really know what leaving looked like. No one had ever left them before. They would come home this night to walls with awkward picture-shaped blank spaces, and mom’s familiar-smelling clothes and shampoo and shoes would all be gone.

I had been fortunate enough to find, on Kijiji, a place down the street from our home—a fully-furnished house that I would share with a video game developer named Sean. I didn’t drive, and being only a few houses away would reassure the kids that I was just taking a break. I knew that taking any furniture would upset them too much. My husband wanted everything to remain as normal as possible, at least on his end. My new house looked clean and respectable, and Sean seemed a very amiable roommate. I had found temp work as a secretary in a hospital. Nothing was permanent yet, and that was the way I preferred it. It afforded me the opportunity to change my mind. This was, after all, the first major life decision I had ever made that was just for me—and I had no idea what I was doing.

I had to accept being separated from my solemn-eyed daughter, for whom I had a secret name (“my rose-brown darling,” from Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita), and my son, who in typical defiant manner looked nothing at all like his family; we are all dark, he a golden-haired child with brine-green eyes. They were brother sun and sister moon, inseparable from each other, inseparable from me. For almost all of the previous 10 years, I had set aside the pursuit of a career to stay home with them. I was the first person they saw every morning and, usually, the last person they saw every night. To be close to them, I volunteered at their school, running programs, organizing fun fairs and bake sales. The tiny details of our intimacy, the way they smelled in different seasons or at different times of day, the contours of their small earnest faces, and the pitches and timbres of their wheedling voices echoing through our drafty old house defined my entire existence.

When I told my friends and family I was just moving down the block, and therefore not really deserting my children, they asked me if it was permanent or only a trial separation. I feigned confidence: I just needed time to sort out some things for myself, away from my husband. Everyone nodded in agreement but smiled uncertainly.

I met Sergei when we were both very young, but he was already mature, and came from an academic family that struck me as close-knit. He’d grown up in a warm home among his parents’ intellectual friends. I came from working-class people with little education who had been raised in harsh, merciless households.

My mother is the second oldest of 14 children. My father was the son of an alcoholic and his child-wife. My parents started a family when they were teenagers, and as they had never been properly parented themselves, they did not know how to nurture their own brood. They had trouble showing affection, though they were very much in love with each other, and never really outgrew adolescence. I was the oldest of three. Both of my younger brothers struggled with addiction, starting in their early teens, after our father left in 1985 to marry a much younger woman, devastating our mother. My oldest brother was killed in an accident when he was 19. The following year, our younger brother dropped out of high school and ran away from home, alternating between jail and homelessness for years. My father retreated further, and my mother and I were left to deal with the grief and tragedy of these two boys. While deeply troubled and disappointed that our family had no vocabulary for healing, I knew I was expected to be a success, to have a “normal” life. I didn’t grieve these sad events until much later, alone.

One year after my brother died, on my 23rd birthday, I married my boyfriend, Sergei. I married his family. I married a better future. I wouldn’t make the same mistakes my parents made.

Our life in 2011 had taken almost two decades to build. When we had both graduated with honours in the humanities (he with a post-grad teaching degree), we married and moved to Russia, because Sergei’s father, an established scholar, had a flat in Moscow. We taught English for two years, then moved to Chicago, where I had earned a full scholarship to Northwestern University for a PhD in art history. My studies were abruptly terminated when I lost my visa to live in the States, and we moved to Toronto in 1997. Disoriented by the seismic shift in my trajectory, I floated around doing odd jobs as a temp while my husband worked on building his career.

In 2000, when I was 29, we bought our first house in a highly diverse east-end Toronto neighbourhood that was beginning to gentrify. The semi-detached house was tiny but charming. That same year, I gave birth to my daughter. My son was born in 2003. We bought a larger house on the same street and spent years renovating it, making it into the home I declared would be the last place I ever lived.

I had everything I’d ever told myself I wanted: a professional husband, a decent home, a daughter and son, and a host of fellow mommies in the neighbourhood. I had stability and community. I had love. However, I had grown reliant on my husband to make the big decisions and, over time, a lot of the small ones too. I found that he had very particular ways of doing things and was highly critical of me. I became fearful of his disapproval and disdain. Over time, I found myself seeking his approval to do simple things on my own, from shopping for food to seeing friends to going for a walk.

After caring for the children all week, my weekends were consumed by family outings, leaving little time for myself. One Sunday afternoon, I accompanied a friend to look at a house she was considering buying, arriving home an hour later than expected (I didn’t have a cellphone). Sergei chastised me in front of her. I apologized, as I always did, but I also saw the situation through my friend’s eyes and was deeply embarrassed. She didn’t know this was normal for me. If I wasn’t at home, I was with Sergei. I had never been to a movie alone, or to a restaurant by myself—except once. I still have a note Sergei left me on my birthday: “Have a drink on a patio, buy a guilty mag, guilt free. But be home by 6.”

But there was one thing I never sought permission to do: write.

As a writer, I built worlds that I controlled, in which my characters did things I had never done and would never dare do. I started writing stories when I was 10 years old, wrote my first novel when I was 12, and finished other pieces, including screenplays, short stories, and plays, in the ensuing years. I wrote almost continuously over the course of my marriage, while the kids were sleeping or on play dates. In 2005, I was brought onboard by some friends to write a play and was surprised when it became a success and was staged two years in a row. In 2007, thanks to a few people I knew in the film industry, one of my screenplays was considered by several Hollywood movie stars. However, I needed legitimacy. I wanted to go back to school and, if I could get into a program, pursue a master of fine arts or a degree in film studies.

In her essay “Mother, Writer, Monster, Maid” in Vela magazine, Rufi Thorpe ruminates on the conflict between “the selfishness of the artist and the selflessness of a mother.” To be a mother is to assume a self-sacrificial role. Fatherhood has its sacrifices as well, though they are perhaps connected more with material obligations than emotional commitments. It isn’t selfish to focus on an intellectually satisfying career if it pays for your kids’ higher educations. I felt like I was betraying one self every time I indulged the needs of the other: while writing, I fretted over not mothering; while mothering, I fretted over not writing. I returned to this theme again and again in my arguments with Sergei, and we could not find a third option, which left me feeling that I had to choose one, commit to it, and abandon the other.

I loved my children and felt confused over the fact that I was slowly becoming invisible, the space between my mind and the real world a widening lacuna. My son and daughter would notice my inattention, frown at me and prod me back into their world of fairy princess Barbie or Playmobil police station to do the funny voices, play the parts, and be one of them. I wanted to live in worlds of my own imagination and retreated there more and more. I thought that if I could get into an MFA program, my writing would be considered more legitimate, more like a career, and I wouldn’t have to feel so guilty about wanting to do it.

Sergei and I could not agree on my going back to school for the arts. There were financial considerations. He was concerned that writing wouldn’t make me any money, and he argued that school could only be justified if it led to a decent-paying job. “How about web design?” I remember him saying. “Or maybe horticulture? You like gardening.” I had also worked temp jobs at law firms, so why not become a legal secretary? I didn’t want to do any of these things. I had an MA in art history but couldn’t even get meaningful volunteer work at any of Toronto’s large museums. I needed a PhD to teach at a university. But I had gotten an MA because I thought I wanted to be an academic, before discovering I hated it.

Why didn’t I just admit I wanted to be a writer and own my truth? Was it really my husband’s fault that I never spoke up? Would he have divorced me had I insisted on doing what I wanted? I was too afraid to find out. I wanted to be normal, and writers weren’t normal. I had never known any writers, but my understanding was that they lived messy, incoherent lives and indulged their selfish needs to be admired. Normal people, on the other hand, were useful.

So I did what I thought Sergei would approve of: I got a contract job as a marketing assistant for a government agency. My boss there was a soft-spoken but fiercely intelligent and hardworking Brit. We shared a similarly dark sense of humour and had tremendous intellectual chemistry. He gave me challenging projects, even hired me to edit a book he was writing for professionals in his field. My interest in him started as a distraction from my problems at home but quickly escalated into a full-blown obsession. He helped me deal with my senses of loneliness and alienation. I shared with him private matters—adolescent heartbreaks, fear of being seen as an impostor—while maintaining a friendly camaraderie at work. But we found that our relationship became strained as our intimacy increased.

I knew it was an infatuation, and it never went anywhere, but the Brit had smashed the notions of myself I’d cultivated during my marriage: that I was disorganized, lazy, and incapable of making sound decisions. My boss treated me like a woman, and it felt amazing to be a woman. How could I have been married to a man for over a decade, borne his children, and never felt like a woman? With the Brit I discovered I had opinions, a mind of my own. He looked at me with admiration and respect. I felt like a character in my own story, a thrilling story of illicit love.

Unable to keep any kind of secret from my spouse, I told him I was in love with another man, and we agreed that I should quit my job immediately. My guilt far exceeded my passion for the Brit, so there was no question of me remaining in his employ. However, quitting triggered a nervous breakdown that lasted for months. I spent most of the summer in bed. Already a thin woman, I lost a frightening amount of weight. I fell into spells of catatonia, sleeping for days, curled in one position, hugging myself, weeping, telling myself over and over that I was a mother and needed to mother myself.

I didn’t know what was wrong with me. At the time, I didn’t understand that my crisis wasn’t because I missed the Brit, but because I didn’t love Sergei anymore, and perhaps never had. I knew I had to leave him, because I felt that he would never see me as anything other than a child. My body suffered the shock of this reality long before my mind could process it.

I remember one day after school, my daughter and son stood in my doorway, watching their mother weep in bed. My son, always querying, said in his lisp, “Why is mom always sleeping and crying? Crying and sleeping?”

“She’s sick,” said his authoritative sister. “She needs to sleep and cry to get better.” Sleeping and crying are medicine? Sometimes, that’s true. I eventually got up and resumed my household duties. There was no talk of me going back to work. I went through the motions of being a wife and mother, and Sergei must have noticed my detachment—I looked despondent often—but we never addressed it. I started writing in secret again and took to drinking in the late afternoons, in the back garden. Booze and cigarettes replaced sleeping and crying. They comforted me the way my daughter’s ratty baby blanket soothed her. Growing up, booze and cigarettes were so ubiquitous in our household that I thought they were a food group. It seemed natural for me to turn to them when feeling shitty and sorry for myself. I was back to being another child in the household. This went on for two and a half years.

I don’t remember much about that time. I remember places, people, and moments—but I wasn’t actually present for any of it. I kept a diary sporadically, and in 2009 I wrote: “Embracing [my son] when he got out of the bath tonight I looked in the mirror and saw a strange woman there, a woman I didn’t recognize, with a little blond child in her arms, depending on her to always be there, when she can’t even be there for herself.” I was terrified that my children would grow up and see their mother as a fraud. I was convinced that I had manufactured these two people to be disappointed in me. .

In 2011, my mother invited me on an all-expenses-paid trip to Paris for my 40th birthday. Naturally, I wanted Sergei’s permission, and I remember him saying no, that he didn’t want me to go to Paris without him, and besides, what might happen? My mother was appalled. “You’re an adult, and I’m hardly going to get you in trouble,” she said. I thought: Why does he think I would get into trouble? Why does he always assume the worst from me? Why do I need his permission in the first place? Then I thought of all the other times I’d asked his permission, and it dawned on me, slowly, that I had never said, “I’m doing this” to him, ever. I’d only said, “May I do this?” He had never insisted that I ask permission; it was merely assumed. He had taken a ski trip on his own, without the family, but then again he earned the most money, which I understood to mean that he had earned his freedom. He didn’t need my permission to do anything.

I was turning 40, and this had been my life since I married at 23. After fighting about the Paris trip, I told him that I didn’t hate him, but I hated who I was with him. I can say now that I did indeed hate him. I asked for a separation only a few weeks later, after a disastrous family vacation—skiing—on Valentine’s Day. Because I was terrified of telling him what to do, I announced that I would be the one to leave. I remember that we were in our bedroom on a Sunday morning before church, and Sergei was putting on his socks. He gazed at me wearily, sighed and said, “Fine. Leave.”

C.S. Lewis writes that seeking enlightenment starts with dismay. I didn’t love Sergei, but I needed him. It is terrible to need someone you don’t love. I wanted to write, yes, but I knew that in order to write authentically, I needed to live authentically. I didn’t know what that looked like and was ashamed that I didn’t know. I suspected that Sergei was ashamed of me too; he told me he didn’t want me to remain a child, but he couldn’t treat me like an adult until I acted like one. I decided I needed to figure that out, alone.

When I left, I didn’t know who I would become, and in all my naïveté, I expected to go back. I thought I would properly love Sergei, and he would love me, once I turned into the person I was meant to be. I chose a temporary situation in order to work out the problems in my marriage. Within weeks, however, I knew I would never return. Though it would cause me endless anguish later, I relished my independence and sacrificed parental responsibility for what I believed was my hard-won freedom.

I was quite drunk and sun-dazed as I walked the block to Sean’s house. Haphazardly loaded items fell from the wagon every few feet. Bending over to retrieve them, I felt dizzy, close to blacking out. The August sun was fierce, the air close and cloying, smelling of scorched grass. I lurched past our very first house, where my son was born, where my daughter learned to walk. My neighbours must have seen me; they all knew me; I had babysat their children, and they had cared for mine. We had shared food during the blackout of 2003, and we greeted one another every day. Were they standing in their windows watching me? Perplexed by me? Sorry for me? Thinking I was batshit crazy?

In the front room I unloaded suitcases that I would later find were full of winter clothes—never pack drunk. I didn’t have a bed yet, so I lurched back to my house and passed out on the basement sofa, where I had been camping all summer. I remember my husband coming home with the kids and finding me awake, still drunk, in tears. He shooed the kids to go watch TV so they wouldn’t have to see mom, snotty and dishevelled, stinking of vodka and cigarettes, clutching herself silently.

What had seemed like a reasonable decision a few weeks before had revealed itself to be a gross distortion of my original intent. I had let everyone down. I was a terrible person. In my drunken state, I mourned the good version of me that had fled long ago, abandoning me for some reason. What had I done to drive away the good mother, the nice wife, the patient daughter-in-law, the friendly neighbour? Sergei tried to put his arm around me, but I resisted: I didn’t deserve comforting. He led me to bed, where I fell into a heavy sleep. He slept on the basement sofa. I dreamt that my new home was a hole the size of a coffin cut into a wall along a busy commercial street, a hole into which I could only creep and lie flat on my back for all passers-by to see. I knew that, when I woke, I would be without a home.

The mattress arrived at my new house two days later, and I moved in with Sean. It wasn’t a big house, yet it seemed hollow to me, even with another person in it. Sean didn’t care what I did with my time, because he wasn’t my friend or my lover or my family member. We chatted over dinner, and he left me at the kitchen table to go back to work in his office. Sitting alone, I wondered: have my children finished eating now? Whose turn is it for their bath? I could smell their sun-toasted skin. My son’s hair always got curlier in humidity and would be damp at the roots. My daughter’s long legs, after a day in the sun, would be tawny as a deer’s. I could see her bent head, her sleek brown bob, as she pored over a book on the sofa. Books were always her refuge from sorrow. My son would be more restless, more anxious, asking his dad questions: “When is Mom coming back? Why did she leave? Does she still like us? When is she coming back? I want her to come back now! Change her mind!” And Sergei would shrug, his face agonizingly calm.

I sat on the back veranda with a cigarette and a glass of wine. Crickets whirred. The late summer sun drifted lazily toward the horizon, and its pink-yellow light reminded me of faded Polaroids of me as a small child, reaching my for the candle flame on a cake, me and my brother knobby-kneed next to our father at Storybook Gardens. Around me now all was still, expectant. There were no sounds of children arguing or running up and down the hall before bedtime coming from this house. For the first time in years, I was free from the agony of not being permitted to make decisions for myself. How great if future me could intercede right now, I mused, and report how everything turned out, and reassure me that henceforth all of my decisions would lead to wisdom and fulfillment, my kids would love me no matter what, and escaping with the red wagon would be a story to elicit laughter at parties.

The fact is, I never thought I was undergoing a midlife crisis when I left Sergei. I had only a vague inkling of what the consequences would be. My parents had lost a child and didn’t know how to grieve, had watched their other son disappear into addiction, had relied on me to not screw up my own life but couldn’t show me how. Sergei took over the parental role, and I believed everything he told me about how I should be. My ideas about maturity revolved around duty, not independence. I had never made a decision that wasn’t predicated on another person’s need: for me to be a good wife, a good mother, a good daughter. It took me almost twenty years to realize that you don’t ask anyone’s permission to be an adult.

As my mother’s family likes to say: might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb. In other words, if you’re going to screw up, screw up big. Make it count. Make it unforgettable. Make it unforgivable. Why? Because then you’re no longer responsible for your actions. You’re too fucked up to be fixed. So go into the wilderness, stumble in the brambles and branches, lose your way. Don’t bother leaving any crumbs. You don’t want to get out, and no one is coming to look for you.

Raising my glass in a toast to my children, I whispered, I promise I’ll come back when I’m all grown up.

I poured and drank another glass of wine. And another. And another.