One Saturday night in the winter of 1998, an engineer operating an eastbound freight train passing through Burlington, Ontario, spotted two teenage boys lying across the tracks. They were wearing what looked like school uniforms. It turned out they were seventeen-year-old Matt Toppi and sixteen-year-old Christopher Brown, who had run away from Robert Land Academy, a military-style all-boys boarding school near Niagara Falls, about fifty kilometres away. The engineer later told reporters that he saw one of them get up as the train neared. The boy tried pulling his friend off the track, but it was too late. They were killed instantly. Friends later said the two were fleeing for British Columbia—presumably as far from Robert Land Academy as possible.

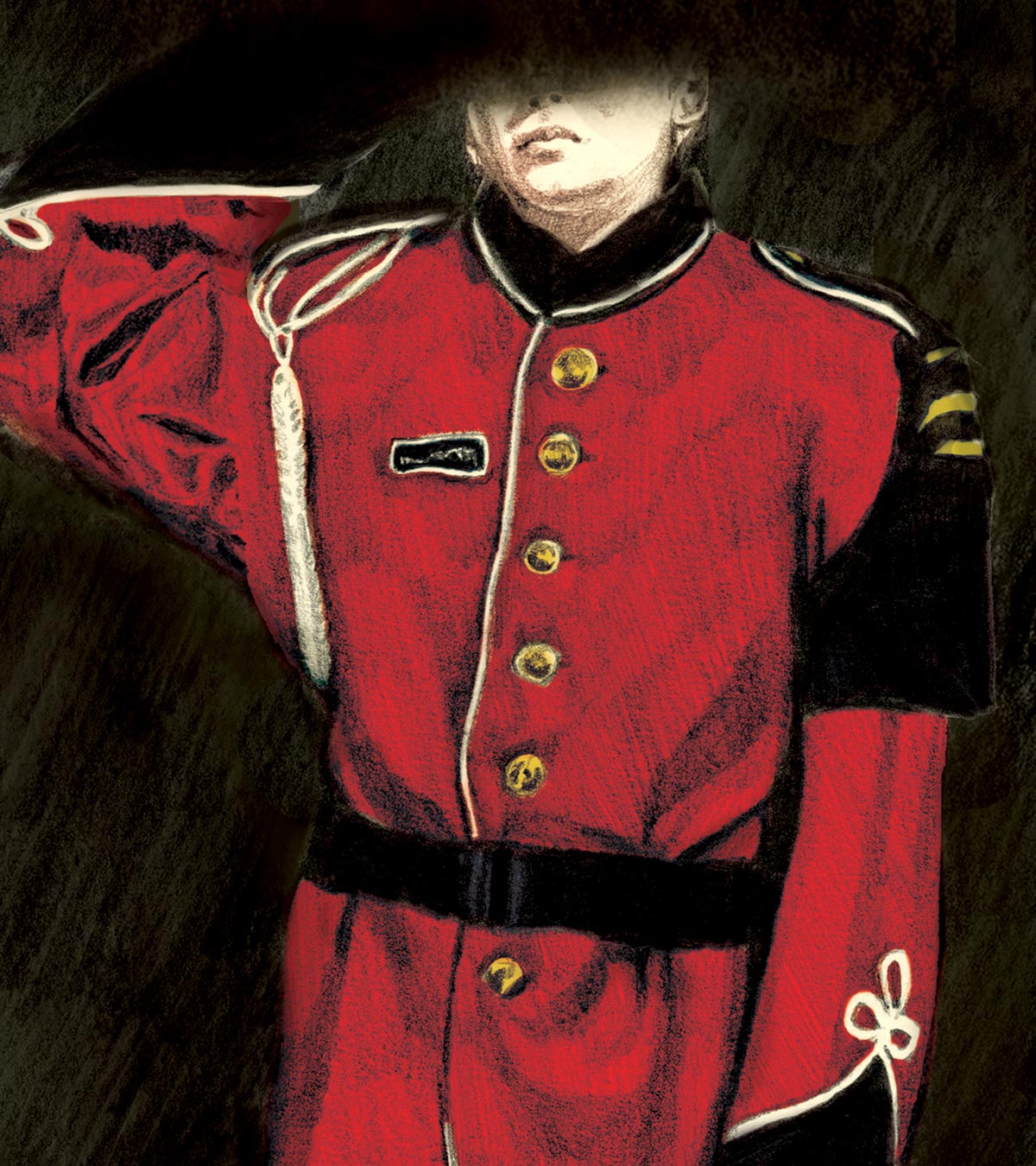

Both Brown’s and Toppi’s funerals were marked by a guard of honour. At Brown’s, nine cadets, wearing crimson tunics adorned with medals, followed the casket into a church. “Christopher did not have an easy life,” said the reverend presiding over the funeral. Toppi’s life was also tough; he had difficulty focusing in class and had run-ins with the law in his hometown. “He was definitely troubled,” the vice principal of the public school Toppi had previously attended told the Toronto Star following the train incident. “That’s one of the reasons he was at [RLA].”

RLA’s intended goal was to turn young boys into strong leaders and citizens. But in the days following the two teenagers’ deaths, former students started opening up to media about the academy. One described it as a “living nightmare,” while another confessed to having been subjected to physical harassment in the form of punishments and initiation rites. Many were unable to cope with the school’s gruelling regime that mimicked army training. “It made me worse,” another student said.

Years later, Brown and Toppi’s tragedy had mostly been forgotten by the public. But within RLA’s walls, it was woven into the school’s culture. Students theorized in hushed tones about what might or might not have happened in the lead-up to the boys’ deaths. Staff allegedly used the story as a threat—if runaways were caught, they would be punished with hundreds of push-ups and laps or put on a “suicide watch” and made to sleep on the floor of a common room. “You were made to feel that [the boys who had run away] were cowards,” one former head boy who attended the school in the mid 2000s told me under condition of anonymity. “If you try to run away and you’re caught, you’re getting three days of hard labour.” Students could also lose access to calling or going home on their next leave or could receive physical punishment.

Over the past year, The Walrus has learned that nearly a dozen people—former students and a parent—have filed multi-million-dollar lawsuits against, or are planning to sue, RLA over a series of alleged abuses that former students experienced from the 1980s to the present. The allegations include physical and emotional violence by staff, racism, withholding of food, sleep deprivation, and sexual assault by fellow students that they say the school overlooked. The Walrus has obtained numerous statements of claim; the academy has not filed statements of defence.

Martin, who requested to go by only his first name, attended RLA starting in 2006, when he was twelve years old, after struggling in school; his parents believed a place with more structure would help. In his statement of claim, Martin states that, while at RLA, an older student who was tasked with overseeing him repeatedly abused him sexually, verbally, and physically. He is suing RLA for $5 million. The school administrators, Martin alleges, failed to document his abuser’s offences, warn teachers and other students about his abuser, and put in place reporting mechanisms and counselling. “They didn’t want me to talk to my parents about it,” he told me. “I always knew I hated it [there], but I just thought I had to kind of eat shit on the whole matter for a long time.”

Staff, he notes in his statement of claim, wilfully did not see the abuse and maintained what he calls “a system . . . designed to cover-up the existence of such behaviour.” Several former students allege in statements of claim as well as in interviews that a culture of fear and abuse was enabled by the school’s founder and former headmaster, Scott Bowman, and by other teachers and administrators. In a statement to The Walrus, Robert Land Academy noted, “The safety and well-being of our students is our top priority and these alleged incidents do not reflect the values of the school, past or present,” and that the school “will not comment on the specific allegations or individuals at this time.” (I reached out to Bowman for comment via LinkedIn. He declined an interview request and told The Walrus to direct questions to RLA.)

The former students’ stories, and their previously unreported lawsuits, echo growing concerns over North America’s largely unregulated “troubled teen industry” as mental health and behavioural issues among young people are on the rise, leaving many parents and caregivers desperate for what they are sold as a lifeline to help improve the lives of their children.

Residential school programs for youth with behavioural issues go by many names, including therapeutic boarding schools or adolescent treatment centres. They typically claim to offer a mix of standard education, mental health or behavioural treatment, and wilderness or sports programs. Some youth are sent to these programs by parents or guardians seeking specialized attention for their children, or by child welfare or juvenile detention systems. In Canada and the US, these private institutions have become an industry worth, by some estimates, billions. Canadian caregivers often send their children to reform schools in the United States, where there’s a much larger offering: Huffington Post reported in 2020 that around 28,000 children and teens in Ontario alone were awaiting admittance to American boarding programs; 200,000 children with “serious mental health issues” were reported to have no access at all to such services in Ontario. Unlike in the US, where private schools are regulated by states, in Canada, there’s little to no government oversight of private schools, including those like RLA.

Some former students say RLA’s strict military-style regime benefited them by providing them with structure. Others maintain that physical and psychological punishments should never be used against children and that they, in fact, prolong the very issues students were sent to RLA to address. As adults, many have post-traumatic stress disorder or anxiety, in some cases leading to homelessness and criminality. Matthew Lefave, the lawyer representing more than ten clients in separate lawsuits against RLA, says that the school tends to send kids “down a far worse path.”

In 1978, twenty-seven-year-old G. Scott Bowman purchased a vacant, rundown barn on 168 acres of farmland in Wellandport on the Niagara Peninsula. After landscaping the grounds and erecting new buildings, he eventually opened Robert Land Academy. Bowman named the school after Captain Robert Land, an eighteenth-century United Empire Loyalist and spy for the British Army who was one of the first British settlers in Hamilton. Bowman, a sixth-generation descendant of Land, became headmaster and positioned the school as a place to turn young boys—those who struggled in public school, had learning disabilities, or had committed crimes—into productive citizens. A 1998 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette describes it as a place for boys who weren’t wanted anywhere else. “Where others see a problem, we see a leader,” the school’s promotional materials later stated. The school began with twenty-eight students, who in the early days called themselves the “Bowman Bunch,” growing to around 125 today. Annual tuition (with scholarships available) costs at least $64,000.

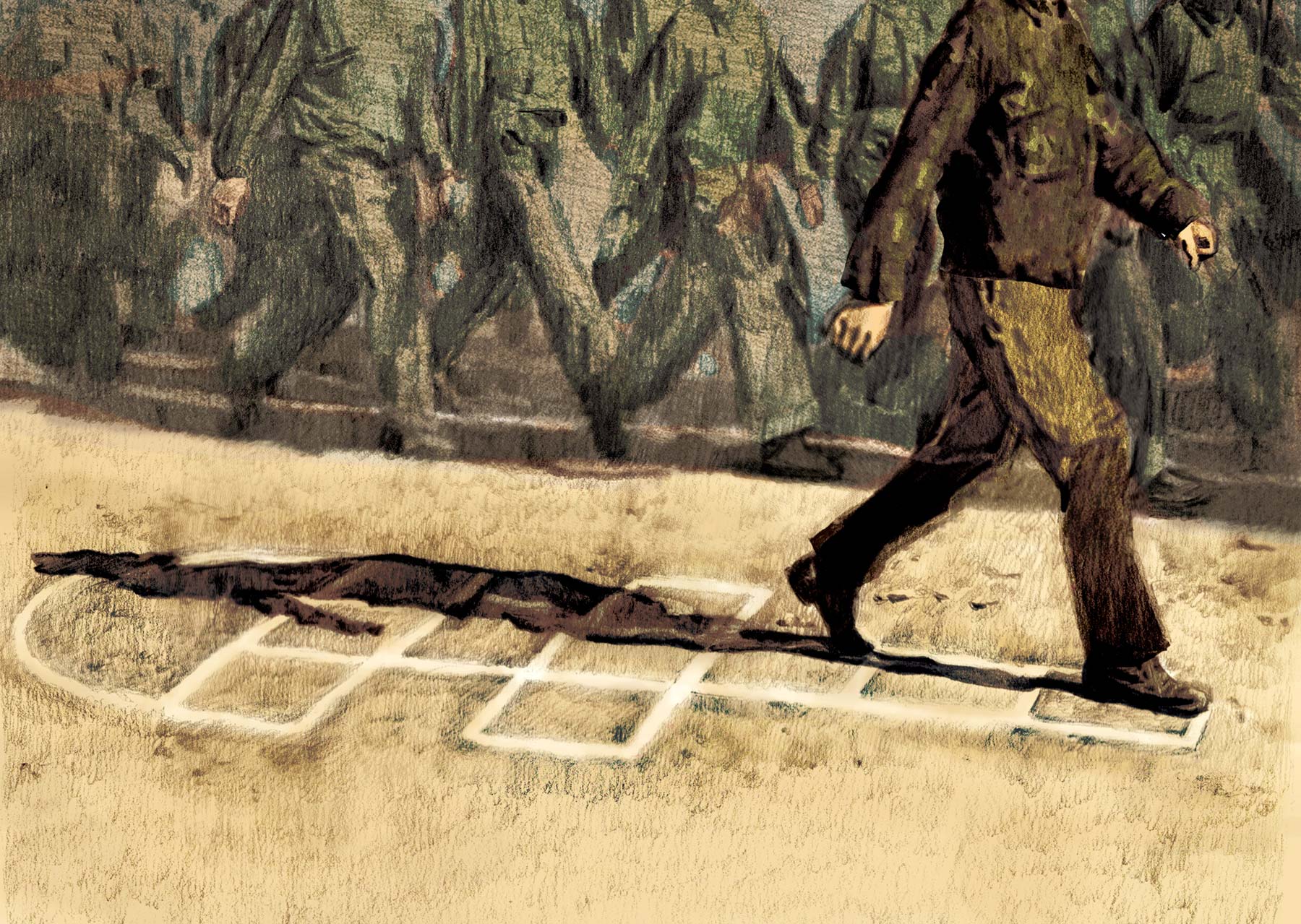

RLA mirrors an actual military establishment, inside and out. Major Bowman—as he called himself—boasted a military pedigree that he used to promote the school as a place of order, rigour, and high standards. The campus is modelled after a nineteenth-century British fort, with a parade square in the centre, barracks where the students sleep, and a mess hall. Military-inspired ranks and titles are assigned to everyone at RLA, with “recruits” and “cadets” the lowest and “sergeant” and “warrant officer” the highest. Typically, upon arrival at RLA, students are made to replace their civilian clothing with red uniforms. The first month serves as an initiation period, during which, for some former attendees, some of the harshest forms of punishment and abuse, both by staff and other students, have taken place. One former student said he was hit with a walking stick and forced to have his pubic hair shaved as part of an initiation rite. Wake-up is at 6 a.m. sharp, sometimes earlier, after which students prepare for an inspection of their bed area by a sergeant-major. If the student fails the inspection, consequences could include the sergeant-major throwing their belongings on the floor and physically pushing them. “Some days you would get full-day punishments, including yard work around the school,” recalls Anthony Duffney in an interview. He attended RLA from 2003 to 2005, from age thirteen to fifteen, after, he says, his parents became frustrated with his misbehaviour at home.

Martin says that, during his initiation period, he was forced to perform push-ups, and when he didn’t do them correctly, a staff member lifted him up and slammed his body to the ground. Students must stand at attention and salute at the request of instructors, most of whom have never served in the military but go by titles such as lieutenant and captain. “We try to take the best from the military and leave the rest,” Bowman told the Toronto Star in 1995. “We’re not turning out soldiers. Our intent is to turn out good citizens.”

While the school may not have been turning out soldiers, it also wasn’t dealing with adults who could leave at any time. The school accepts students from grades five to twelve, from around eleven years old to around eighteen, and most are sent there by their parents. It’s a fraught and formative time, during which traumas, even short-lived ones, can have consequences that linger long after students depart or graduate.

One former RLA Student, who is now seventeen, alleged in documents filed at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario in 2021 that he experienced emotional and physical abuse as well as anti-Black racism when he attended the school in the fall of 2019. “Upon arrival to the school, I was subjected to cruel and unusual treatment,” the boy, who must be kept anonymous because he’s a minor, noted. He alleges he was harassed by staff, who would smack books out of his hands while he was reading and call him a “mama’s boy”; once, a staff member pushed his knee into his back. “Over and over I was emotionally tortured. Making me feel like I was a prisoner,” he continued in a tribunal document. “I was told I could not contact my Father, after asking many times. I was chastised many times and told I was worthless.” The boy claimed he was forced to wear a “suit of shame” and he urinated himself while wearing it. “To this day, I still have urination issues.” (The Human Rights Tribunal complaint was later abandoned; the former student is now a client of Lefave.)

A version of RLA’s parent handbook from the 2019/20 school year includes a page devoted to “Discipline Expectations” that describes how “the purpose of progressive discipline is to change behaviour and to develop self-regulation.” Consequences for “poor choices,” the guide states, may come in the forms of “laps, physical exercise, loss of privileges, extra chores, suspension from regular duties, loss of leaves and stand downs, or dismissal.” It does not mention students facing any type of corporal punishment.

According to a 2010 report by The Canadian Historical Review, corporal punishment against children and students was condoned well into the 1960s, a time when children were seen to be subordinate and in need of harsh correction by any authority figure, from parents to religious leaders to teachers. The strap, in particular, was used as a disciplinary weapon in schools across Canada. Reforms to the public school system took place around the 1960s, during a surge of elementary and secondary school enrolment in the postwar period. Teachers and administrators began embracing a more child-centric approach to pedagogy. Corporal punishment was one of the many aspects of the old system that came under intense scrutiny.

In 1968, a report by the Ontario government recommended ending corporal punishment in schools. By 1971, Toronto’s board of education became the first in Ontario to prohibit the use of the strap. But physical discipline was not formally abolished from Canadian schools until 2004, when the Supreme Court narrowed down the law, ruling that parents and caregivers may use “corrective force (or physical punishment) that is minor or ‘transitory and trifling’ in nature” and that “teachers cannot use force for physical punishment under any circumstances.” Teachers may be permitted to use “reasonable force,” such as removing a child from the classroom, in specific instances.

Research has linked physical punishment against children with long-term negative impacts such as increased aggression, higher rates of anxiety and depression, challenges with emotional regulation, and changes to the brain’s development similar to what is seen in those who experience sexual and other forms of severe abuse. Existing learning and behavioural issues can be exacerbated by physical punishment.

I spoke with ten former students, many of whom said that physical punishment by staff and violence among students were regular occurrences and were overlooked by staff. In particular, they spoke about the use of restraint manoeuvres, prohibited by Canadian law, as a disciplinary tactic. “There were always kids that were getting restrained on the ground by staff,” says Leon Duperre, who attended RLA from 2009 to 2010, in an interview. Duffney claims he was put in excruciating positions multiple times a year and routinely saw other students endure them. He says staff would grab students’ right or left arm and swing it up behind the back so it touched the shoulder blades. “And then they’d put their hand underneath your elbow and just lift until you’d go limp.” RLA said in a statement to The Walrus that the school maintains “a clear and strict zero-tolerance policy regarding corporal punishment and the use of physical restraints” but did not comment about these specific allegations.

Evan Holmes attended RLA in his mid teens, from 1998 until 2000, and is suing the school. He says he has struggled with mental health issues and homelessness since graduating. He alleges in an interview that he was physically restrained by staff repeatedly—“twist you into a pretzel and hold you so that you can’t move,” he recalls—and was forced to spend time outside in the winter months as punishment for poor behaviour, something commonly reported by former students. “I left there not caring whether I lived or died,” he says.

Former students claim they were not allowed to seal the letters they mailed home, and that phone calls were restricted. Some students suspect both were monitored. (RLA noted in a statement that “staff are not permitted to read students’ emails or letters” and that the school “support[s] and encourage[s] regular communication between students and their parents or caregivers.”) Isolation and an inability to report can create an environment where abuse can fester, says Sarah Golightley, a social work assistant professor at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow who researches institutional child abuse in so-called therapeutic boarding schools. This is compounded by “betrayal trauma,” through abuse by adults who are supposed to care for you as a child.”

Golightley acknowledges that there are cases where a child would benefit from living and learning away from home, but this must be done in ways that are empowering, such as with the child’s consent. “I do think there are situations where being outside of the family home in a caring environment is sometimes useful and necessary,” says Golightley, herself a survivor of a therapeutic boarding school, “but these legacies of violence are so entrenched that I think it’s beyond reform.”

In the years leading up to the train tragedy, Bowman and the school were open about their disciplinary tactics and harsh treatment of students. An episode of the CBC’s The Fifth Estate from 1981 shows young boys struggling to lift cement bricks and another boy running around a soccer field with a backpack weighing upward of thirty-five pounds. “When boys choose to challenge the structure in a negative way, yes, very clearly the consequences are laid out before them,” Bowman tells the host in a sit-down interview.

Nearly a decade later, in the early ’90s, a segment of the news program Canada Tonight showed Bowman demonstrating how staff used physical restraints against students—years after the provincial report recommended against corporal punishment in schools. “A code of discipline some might regard as draconian,” the host states. “You may choose to get into the push-up position under your own steam. Or you may choose not to do that,” Bowman says to the interviewer. “If you choose not to do that by the time I count to three, I will put you in that push-up position.” When the host asks Bowman how exactly he does that, Bowman smiles and says, “It’s really quite simple.” The host eggs him on: “Do it!” Bowman places the host’s arm behind his back and forces him—albeit lightly for the demonstration—to the ground.

Bowman eventually came under personal scrutiny. According to a 1996 investigation by the Hamilton Spectator, Bowman professed links to the Canadian military and frequently pointed to his work as an intelligence officer for NATO and his national security work for “the Israelis” in Lebanon. He claimed that his body bore a bullet hole and 400 stitches as a result of combat. In an interview with the newspaper, a reporter quizzed Bowman about his history and requested a copy of his résumé, which apparently claimed that he had twenty years of service with NATO in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. “Checks on the claims came up empty,” the reporter concluded. But neither this revelation nor the train tragedy appeared to significantly damage the school’s reputation.

But stories did emerge. Days after the train incident, a local doctor told the Hamilton Spectator that two students with bone fractures had been left unattended, including one boy who had run away twice before. One of those boys, the doctor said, was “supposed to be carrying around a bag of sand on his back and lying on the ground pulling weeds.” Five years later, in 2003, parents of RLA students told the National Post their children had been put in isolation rooms for weeks at a time and made to endure group punishments, including forced marches with twenty-pound “lap jackets” at 4 a.m. “They say their children were called ‘retards’ and ‘idiots,’” the article notes, “fed rations and made to spend hours digging ditches at the expense of their studies.” Then, one Sunday evening in November 2010, the mother of eighteen-year-old RLA student Donald MacNeil was driving him from Halifax back to the school after a term break. According to CHCH-TV, he jumped out of the car and ran into traffic, where he was struck by an oncoming vehicle and died. (RLA did not comment on these allegations or this incident.)

By 2012, after more than a decade of stories, both public and whispered, negativity around RLA seemed to have been overshadowed by positive news coverage of how the academy had improved the lives of teens. The school seemed eager to focus on what they considered to be the pros of a military-style education, such as strict schedules and physical activity, rather than the hard labour and physical abuse. Bowman, for his part, seemed to no longer showcase the school’s disciplinary code as he had in years past. “Tough love turns students around,” reads the headline of one 2012 Toronto Star article, which noted that nearly 70 percent of RLA’s students had been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder—ADD, ADHD, ODD—or learning disabilities. (“We welcome a diverse range of students,” RLA noted in a statement to The Walrus, “representing various nationalities, and varying abilities. The proportion of students who have learning disabilities can vary by age.”)

While the positive coverage continued, the school was able to build an esteemed board of governors and supporters, with Tim Hudak, former Ontario Progressive Conservative leader and current CEO of the Ontario Real Estate Association, currently serving as chair. Much of the rest of the board comprises current and former police officers. In 2023, former Ontario health minister and deputy premier Christine Elliott received an award from the school at its annual gala.

But as RLA’s reputation continued on a positive trajectory, numerous people began posting on a Reddit thread called r/TroubledTeens, swapping stories of abuse or harm they allegedly experienced or witnessed at the school. “I saw countless restraints and maybe like one or two were justified, but usually they were for any kind of disobedience if the staff was in a bad enough mood,” one user, seemingly a former student, wrote in 2023. “Sure I did well academically but holy hell, nothing like ODing after you graduate because all you want to do is die. Never ended up going to university that much is for sure,” another person, who noted he attended the school from 2008 to 2011, posted. Others, however, spoke highly of the school. “The school helps a lot of kids become men and it isn’t easy,” wrote someone who says he attended from 2002 to 2004, “it pushes you to your breaking point and then some but builds on that to grow self esteem and mental health.”

Last year, Martin found community in these forums, he says: he began commenting on Reddit and started groups on Facebook to connect with other former students and to put them in touch with his lawyer, Lefave. It could be years before the lawsuits come to a conclusion, whether by trial or settlement. Martin’s mother is also suing the school, for $2 million in financial, mental, physical, psychological, and emotional damages, for allegedly failing in their duty toward her son, whom she sent to the school believing he was going to receive a high-quality education that would lead to success in life. She told me she blames the school’s “depravity and brutality” for her son’s ongoing trauma and inability to properly care for himself. Martin has struggled with substance use since his late teens and has been in and out of jail.

“A lot of the school staff refuse to acknowledge the truth about how bad [RLA] is,” Martin, now twenty-nine, recently told me. “People lost their entire childhood there.”

If you would like to get in touch regarding your experience at Robert Land Academy: rachelp.browne@gmail.com