Beautiful stage productions take shape in ugly places. Some of London’s most lavish sets are built on a grim industrial wharf; New York’s Metropolitan Opera keeps its stage pieces in a New Jersey storage yard; and the National Ballet of Canada has its headquarters at Toronto’s dreary downtown harbourfront.

Four months ago, in a studio overlooking a tangle of overpasses, National Ballet soloist Tanya Howard tried on a silk tulle gown alongside Toronto-born stage designer Michael Levine. In June, Howard will dance the part of the Rose in Le Petit Prince, an original production based on the beloved French novella by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. With her lofty cheekbones and orb-like eyes, she would look beautiful in anything, but Levine was unimpressed. “It’s very minty, the colour,” he said, frowning as he pointed to the base of the dress. He had envisioned the costume getting gradually lighter, from the dark-green hemline to the flesh-coloured bodice. In the version before him, the hem was too bright and the colour gradient too abrupt. “The legs, which are the rose stem, should turn slowly into the body of a woman,” he explained.

Levine, one of the world’s most renowned stage designers, is based in London. But his work takes him everywhere—from Broadway to the Vienna State Opera to La Scala. His constant globe-trotting meant that he had to submit some of his costume and set sketches for Le Petit Prince electronically, leaving on-the-ground staff to interpret them. Over the past year, he showed up in Toronto for whirlwind consultations during which he was often obliged to explain exactly how the pieces fell short of his vision. “It’s terrible,” he says. “I give people these impossible tasks, then I get back on a plane for Europe.”

Short and every bit as svelte as the dancers he works with, Levine speaks softly, with a hard-to-place transatlantic accent. He has a keen eye for detail and for female beauty—how it can be made radiant with just the right outfit. He loves all materials, from the finest satin to the tackiest polyester. He wants his costumes to be “sexy,” “sensuous,” and “weird.”

Had the National Ballet wanted a simple fairy tale—something like Cinderella or The Nutcracker—it needn’t have splurged on a celebrity designer. But Guillaume Côté, a principal dancer and the show’s creator, insisted that only Levine, with his knack for emotional complexity, could get the tone right. As a seven-year-old in Lac-Saint-Jean, Quebec, Côté danced the Little Prince at the ballet studio where his parents worked. Decades later, during what he describes as his “late-twenties existentialist phase,” he reread the book and realized “it wasn’t just a children’s story after all” but something gloomier and more challenging.

Michael Levine (centre) with Guillaume Côté (far left) and several warehouse technicians.

To hire levine, you must be willing to share creative custody of your work. But that’s part of his allure. “He’s way more than a designer,” says Atom Egoyan, the director who teamed up with Levine on Wagner’s Die Walküre at the Canadian Opera Company. “He’s a full collaborator in the entire conceptual project.”

At the National Ballet, rehearsals for returning productions typically start a month or two before opening night, but since Le Petit Prince was a ground-up affair, the team started three years early. Levine, a creative partner, was present for the initial workshops. He even challenged Côté on choreographic choices—interventions that, for most stage designers, would be way out of line.

Côté, for instance, wanted to use contemporary dance for the role of the Prince, but Levine pushed back. In order to capture the character’s extraterrestrial origins, he argued, lead dancer Dylan Tedaldi should seem weightless. That would mean drawing on classical techniques such as high jumps with outstretched arms and elaborate footwork (what dancers call batterie). Côté, himself a classically trained dancer, worried that too many traditional flourishes would make the work seem old-fashioned, but Levine talked him around. “He reminded me that what I do—classical ballet—is so, so beautiful,” says Côté gratefully. It’s old because it has stood the test of time.

A graduate of the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University), Levine originally considered a career in painting. “The idea of being alone in a room with a white canvass sort of terrified me,” he says. Set design, on the other hand, meant collaboration. After a stint at Glasgow’s wildly prolific Citizens’ Theatre, Levine returned to Canada to shake up the Shaw Festival with multi-level sets that shifted and mutated. Then, in 1988, he got his big break: the Geneva Opera commissioned him on a production of Arrigo Boito’s Mefistofele, for which the twenty-eight-year-old designer conceived a “celestial theatre,” with tiered boxes and ornate candelabra. Levine drew iconography from numerous sources—baroque culture, commedia dell’arte, the Maltese carnival—and even suspended sculptures from the ceiling. The project was so ambitious it bordered on foolishness, but suddenly European companies were competing for his designs.

Classical ballet, with its poufy costumes and painted sets, often looks stuck in the Victorian era. Levine, however, likes video projections, elemental materials such as fire and water, allegorical imagery, and costumes that are more suggestive than explanatory. (In Le Petit Prince, for example, it may take viewers some time to realize that the Rose is a rose.) He sometimes requires performers to double as set pieces. In his production of the opera Oedipus Rex, actors piled up like corpses under the monarch’s bloodstained throne. He may seem like an iconoclast—his works don’t look like anybody else’s—but in his strange way, he’s a traditionalist. He begins each project by rereading the source text in search of hidden themes or visual motifs, which he brings to life on stage.

For Dvořák’s Rusalka—the story of a doomed romance between a human prince and a water nymph—he divided the performance space into two symmetrical sets, to represent the division between mortal and supernatural realms. For a production of La bohème, Levine focused not on the wide Parisian boulevards but on the cheap flophouse in which the artist characters live; the action took place in a cramped loft on an otherwise empty stage. And in his controversial A Midsummer Night’s Dream, at London’s Royal National Theatre, he opted not for the obvious setting—an enchanted forest—but for grimy woodland in which near-naked actors slosh around in puddles of mud. “As the lovers get deeper and deeper into the woods, they get dirtier and dirtier,” says Levine. The play is a raunchy sex comedy; it shouldn’t look like the magical land of Oz.

The notion of a dark, psychologically fraught Le Petit Prince may seem sacrilegious, but that says more about how the book is remembered than it does about the book itself. Sure, the watercolour illustrations are charming, and there’s plenty of humour and warmth in Saint-Exupéry’s storytelling, but a sense of despair hangs over the text like a cloud of ash. During the first half of the book, the boyish Prince leaves his asteroid home and embarks on a grand tour of the adult universe, meeting lonely oddballs—some malevolent, others crippled by narcissism. The characters are peculiar and funny; they’re also frightening, repetitive, and broken.

If Saint-Exupéry had a dim view of adulthood, it’s probably because he was a dismal adult. A world-class aviator, he flew reconnaissance missions over Nazi territory until the French armistice of 1940. He then escaped to Quebec City and later New York, where he wrote Le Petit Prince in 1942. He was a bitter exile who refused to learn English, drank heavily, and cheated on his wife in a series of romantic entanglements (you might call them affairs, except there wasn’t much sex). A vocal critic of Charles de Gaulle, he often suspected his American acquaintances of being Gaullist spies. In a letter to a mistress, he described himself as “so alone, so lost, so bitter.”

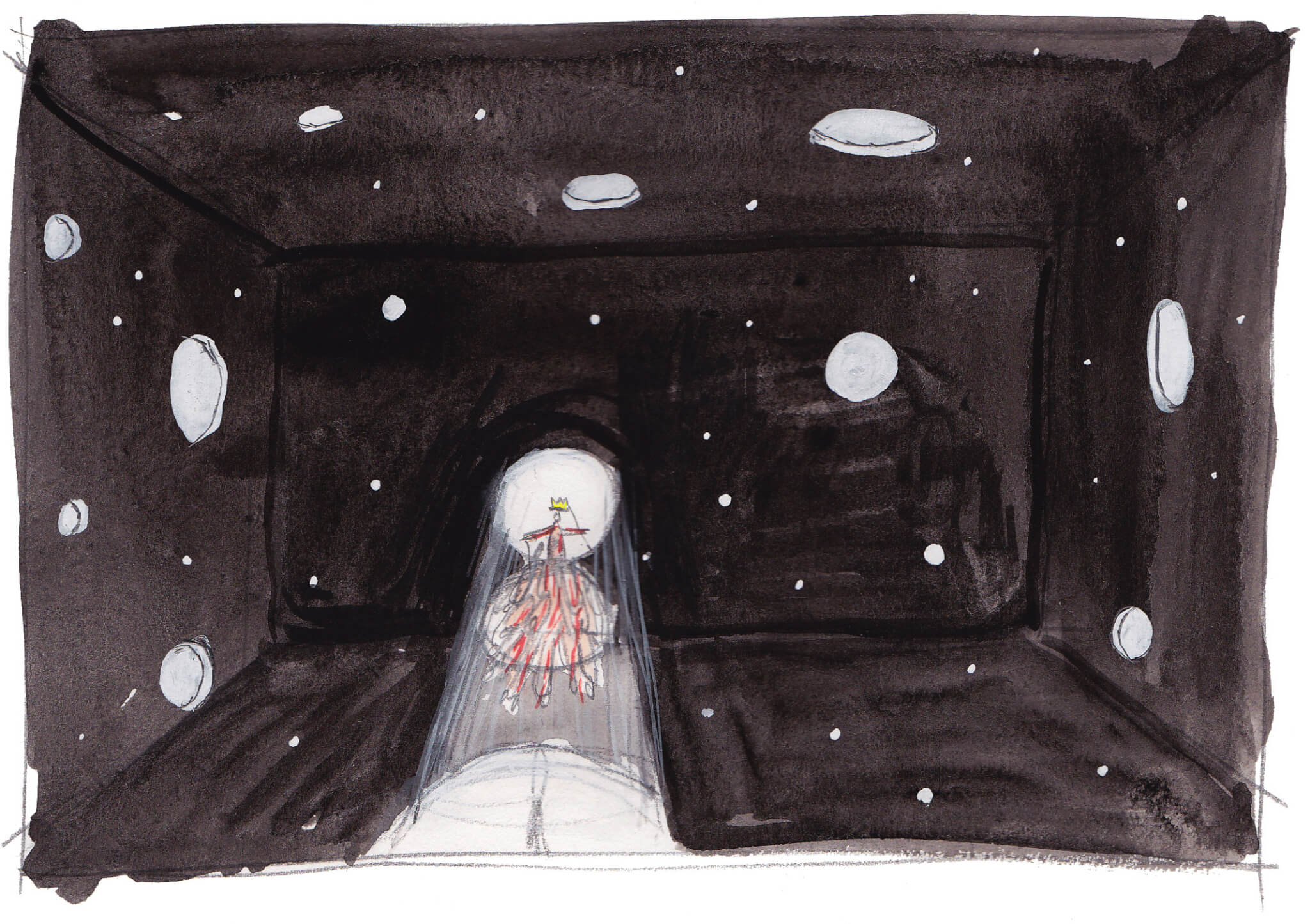

On stage, Levine wanted to reflect both the expansiveness of the cosmos and the claustrophobia of Saint-Exupéry’s psychological world. “People need to feel like they’re inside the author’s mind,” he says. Most stage designers produce digital renderings of their work, but Levine constructed his models for Le Petit Prince the old-school way, from cardboard and glue. “Because I’m making something for the physical world, it should be a physical object,” he explains. He built a star-lined box with circular doors that resemble planets. The full-size version of this structure will encase the entire stage, conveying a sense of confinement—as if outer space were pressing in on the performers.

Just weeks ago, I saw the unfinished product at the National Ballet’s 59,000-square-foot suburban warehouse. (Theatre space downtown at the Four Seasons Centre, where the company performs, costs more than $16,000 a night, so sets remain in storage for as long as possible.) Its walls, consisting of a welded-aluminum latticework, hung like a pergola from the high ceiling. Ponytailed workers stood below, attaching bolts or installing electric motors to operate the planet-doors. Each piece is marked so that it can be taken apart, trucked downtown, and quickly put together onstage. Once the box is fully assembled, the crew will cover it with a sheet of textured black polyester that looks like the Astroturf of some post-apocalyptic ballpark. During the show, this material will catch the overhead lighting and appear, from a distance, to shimmer like stars.

The team is working on other space oddities, too: planets mounted on dolly wheels that will detach from the box so performers can dance with them; perhaps a massive plywood-and-canvass “paper airplane” that will crash through the ceiling; and a motorized rotating chair, set at a forty-five-degree angle to the ground, on which the Prince will perform acrobatics and handstands, demonstrations of weightlessness. The factory crew even load-tested the chair to ensure that it could support the routine: a heavy-set welder sat on it and spun around in circles. “We have to sacrifice ourselves before we sacrifice the dancers,” says Gordon Graham, the technician who built the chair.

Levine’s craftiest inventions are constructed not in the warehouse but back at the harbourfront costume shop. Stage costumes are all about ingenuity—even trickery. The slickest woollen suit is cut from spandex; the shiniest diamonds are made of dollar-store plastic. A production wardrobe is expected to last twenty years or more (reuse is the only way to get a return on investment). When performers share individual roles, they share outfits, too—often appearing in tights soaked with other dancers’ sweat.

For Le Petit Prince, some of Levine’s wardrobe concepts were simple. The Prince’s getup is modelled partly on Tedaldi’s actual street clothes: running shorts and a henley shirt. The material for the Drunk Man’s ensemble was easily sourced online: there’s a prop shop that sells ultra-wrinkly fabric for onstage slobs. For the Crows, who carry the Prince from planet to planet, the costume team constructed birds the same way you would a kite, with polyester stretched over a skeleton of copper rods.

But not all of Levine’s ideas came easily. For the role of the Fox, he envisioned a dancer smeared in red mud, like South Asian kushti wrestlers who brawl in earthen pits. But the conceit was too abstract, so the designer went with a furry-looking tasselled jacket instead. For the Vain Woman (Côté’s take on the novel’s Vain Man), Levine wanted an outfit covered in mirrors—so the company’s wardrobe supervisor, Marjory Fielding, glued pieces of reflective vinyl to a tutu. The material curled and bulged, resembling the exoskeleton of a giant cockroach. For her second try, Fielding cut shards of thin reflective plastic—the stuff from which sequins are made—which she then sewed into the dress. This time, she got the desired effect.

Levine’s toughest challenge was the Snake, who bites the Prince at the end of the story, either killing him or sending him back to his planet, depending on your interpretation. The figure had to look sinister and serpentine but not campy. Levine first drew arm-length red gloves to be worn over black tights, evoking a red-tongued serpent. He then scrapped the plan in favour of a body-stocking patterned like a snakeskin tattoo. Neither was a great idea: if the first evokes a burlesque show, the second belongs in a strip club for bikers.

In the end, Levine opted for three silk gowns—one flesh-toned, one pink, and one bluish-green—to be worn on top of one another. The dancer would take off the two outer layers during the performance, as if shedding her skin. “It’s sexy, alluring, and beautiful at the same time,” says Levine. It’s also vaguely grotesque, I added. “Yes,” he said, smiling. “It’s that, too.”

Adesigner creates a visual universe, but it’s up to the dancers to give it meaning. Last March, in a mirror-lined rehearsal studio at the Four Seasons Centre, Côté worked on a pas de deux (a two-person, mixed-gender routine) with Tedaldi and Howard. I’m used to seeing ballets from the cheap seats; from up there, the performances seem remote and flawless. Move closer, and the experience is more visceral. Tedaldi’s arm muscles shake as he lifts Howard in the air, and both dancers groan and grunt during moments of strain. To dance in a ballet, you must be comfortable wedging your fingers into your co-worker’s armpits. It’s an inescapably intimate art form.

Tedaldi can’t seem to pick Howard up without accidentally pulling her hair. In fact, Howard’s hair has been a problem ever since Levine forbade her from tying it back, insisting that it’s part of her costume. Together, Howard and Côté devise a movement in which she sweeps her hair aside, taking it away from wherever Tedaldi’s hand will grab her. The act should look, to the audience, like a narcissistic flourish. Really, though, it’s a way to avoid getting hurt.

Although Côté’s choreography borrows from modern dance, gymnastics, and even breakdancing, the pas de deux, like much of the production, is broadly classical. The Prince is preparing to leave the Rose behind on their lonely asteroid, and he has no plans to return. His feelings toward her oscillate between annoyance and emotional dependence, and, though she loves him, she also resents his coldness. Côté’s job is to explain these dynamics without words. He tells Tedaldi to push Howard away from him, then chase her desperately as she jetés across the stage. Later, when Tedaldi lifts Howard into the air, her body will stiffen with anger. After a split second, though, she’ll relax, accepting his affection despite her bitterness. The scene is fraught and unbelievably sad, which is just how Levine wants it.

The show will end with a video of the Prince dancing on a table, his body getting smaller and smaller as it disappears into space. If it seems like a grim conclusion, consider this: After writing Le Petit Prince, Saint-Exupéry enlisted in the resurgent French Army. On July 31, 1944, he took off from a Corsican airfield and headed toward southern France on a reconnaissance mission. He never returned. Nobody knows what happened, but the night before his departure, Saint-Exupéry wrote to his mistress about his “breathtaking indifference” to life.