Shortly before last November’s announcement that Kim Collier had won Canada’s largest annual theatre award—the $100,000 Siminovitch Prize—the director sat in a soulless chain restaurant in Vancouver’s South Granville neighbourhood with her husband, Jonathon Young, writing thank-you cards and stuffing bottles of wine into gift bags. They were both nervous. It was opening night, and Collier was directing her husband in their theatre company’s most daring work to date.

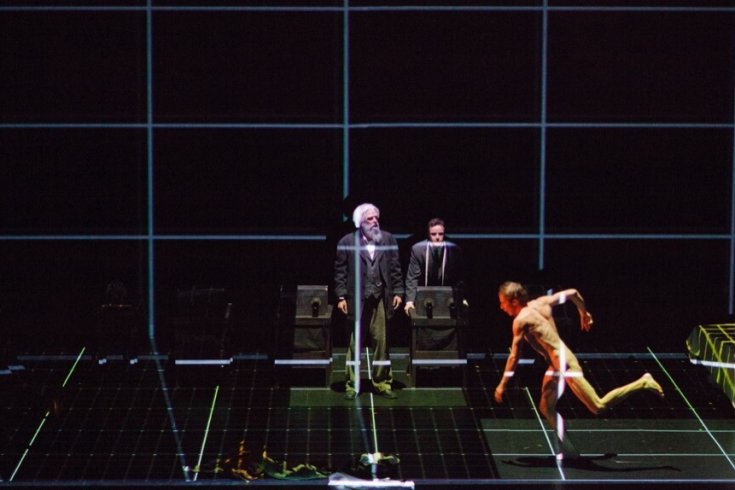

A team of 100 actors, designers, technicians, and filmmakers had entered into the highly complex project with Collier and Young’s Electric Company Theatre. Part film, part play, Tear the Curtain! is set in the 1930s and dissects the war between the two media. Its hero, played by Young, is a twee theatre critic, surrounded by clichéd characters (the mobster, the femme fatale), and engaged in a geekish, all-consuming search for authenticity. There’s a secret society of authentic artists, which the critic cannot contact. Indeed, the character is almost aware that he’s trapped in the cage of a play.

Conceiving the work had been a highly cerebral, nearly untenable endeavour. “We propose,” Young explained to me a few months later, “a world where life is an illusion and there’s nothing behind it except another illusion. It’s my character’s ultimate fear. And it’s mine, too.”

They rewrote the play during rehearsals. Collier, whose directing binder grew to be 15 centimetres thick, wept in the bathtub and was wracked by serious doubts as to whether she could pull off the production. At one point, Young gave up on the work (it’s standard practice for him to be intimidated by the complexities of his creations) and needed to be buoyed along by Collier (also standard practice).

When the pair walked to the theatre on opening night, two hours before showtime, crowds had already formed; a notoriously late theatre audience was eager to see what happens when the city’s greatest indie company gets into bed with the Arts Club, the city’s largest production company. Collier told Young, “You need to just give it all away. Now is the moment.”

Young’s performance that night was a revelation. The work is ambitious and immense. There is scene after scene of a splintered plot line involving gangsters, lovers, secret societies; the production becomes deliberately chaotic to parallel its hero’s crisis. There are several moments when the room the audience sits in becomes reflected, or projected, onto the stage, disrupting their passive consumption of the entertainment. Young moves like a dancer, more poised and more precise, even as his character loses control and suffers a breakdown. In the final scene, the critic and his girlfriend slide down into the audience to watch a movie—thus conflating the immediacy of live bodies and the pleasant numbness of watching a film.

Young later told me he heard an internal voice that night—a small one, calling out to the audience, “Just listen. Just go with me.” In the lobby afterwards, a couple of people were in tears. There was champagne. Collier and Young went out for more drinks with the actors, eventually ending up on a street corner talking about life, about their fourteen-year-old daughter, Azra, who had died the year before.

The couple doesn’t speak publicly about her death, but, inescapably, the tragedy has become part of the conversations that surround their work. Young thought of his daughter every night of the show’s run, often while onstage. How could life and art not collapse into each other? On opening night, a desperate, shaking man tore himself apart, and then, in the play’s final, graceful scene, he gave in to the necessary solace that art provides: Young walked down into the stalls and sat among us, literally joining the escapist crowd.

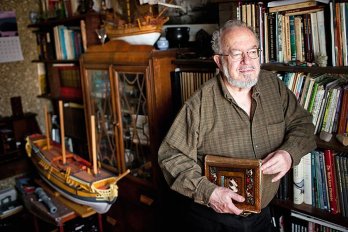

Collier and young have drifted into each other as much as their lives have drifted into their art. Early this year, I sat between them at a long table in their Progress Lab 1422, a converted factory space in East Vancouver, and had the distinct feeling of being sandwiched by two chattering hemispheres of a single brain. They finish each other’s sentences with casual ease; they quarrel lightly over semiotics, and issue compliments to each other with a deadpan assertiveness, compliments they each accept matter-of-factly, like spoonfuls of medicine. Both are slim and good looking, with intensely drawn features and vulnerable eyes, which makes them seem wise even before they start talking about “the intelligence of the body” or “cultures of mediation.” He tends toward layers and scarves, while she prefers simpler, monochromatic outfits.

Since its inception in 1996, Electric Company has built a dazzling repertoire. Aside from Collier and Young, there are two full-time staff and three part-timers, and an annual operating budget of around $1 million. David Abel, managing director of Canadian Stage in Toronto, one of the country’s largest non-profit theatre companies, describes Electric Company as “the only company in Canada doing that kind of physical and visually oriented work on such a grand scale.” Norman Armour, a kingpin of the West Coast theatre scene, says they’ve been at the centre of a Vancouver theatre renaissance. “I can’t imagine our contemporary English Canadian theatre without their unique contributions,” he says. Electric Company is at once independent and firmly entrenched; in certain circles, attending one of their productions is as unthinkingly mandatory as showing up for opening night at the Vancouver Opera.

Young was eighteen when he left his hometown, Vernon, British Columbia, and enrolled in Vancouver’s prestigious Studio 58 acting program in 1992. There he distinguished himself as a charming and talented young man, but one with an appalling work ethic. He was sent away for a year, and decided to hitchhike to Central America.

Meanwhile, Collier, eight years his senior, had been reading armloads of books on metaphysics, and living a gypsy life. She arrived at Studio 58 in 1991 and played Phoebe, the forest nymph, in the school’s production of As You Like It. Young, newly readmitted, was part of the backstage crew.

At the opening night party, when Collier saw the strange boy in the hippie clothes with the magnetic aura, she thought, “That’s the sort of person I should be with.” She reminded him of a woman he knew back home. A mother. Collier became pregnant five months after graduation. She had no career, no money. And Young, the baby’s father, was only twenty-one.

They founded Electric Company with two friends, to create the kind of highly visual, avant-garde multimedia works that normally fail to attract mainstream audiences. The pair have worked and lived together ever since. “I feel that many couples must run out of things to say to each other,” Collier says. “But with us, there’s always been some argument or debate to wade through.” They share exacting standards: their plays are meticulously worked over and remixed, and sometimes produced in multiple forms. Soon after they founded the company, Collier was recognized by her peers as a visionary director. Meanwhile, Young, made serious by love and parenthood, became a technically accomplished actor. In the early days, they produced shows while raising their daughter and taking turns working second jobs.

“It was so intense,” Collier says. “But we could do it because we had everything ahead of us and nothing behind us.”

Young nods across the table at her. “Although,” he says, “sometimes we do repeat time.”

“Yes,” she agrees, then looks at him and says, “What do you mean? ”

“I mean time doesn’t always go forward,” Young says. “We can repeat the past.”

Indeed, their work can be viewed as an obsessive revisiting of certain unsolvable problems: How does art engage with life? How do we escape our stories or succumb to them? And, most significant: How is it that art can at once save and destroy us?

In their 2004 production Palace Grand, a prospector holes up in a theatre and writes his memoirs. Two years later, in Studies in Motion, the company created a haunted version of Eadweard Muybridge, the nineteenth-century inventor who captured motion with rapid-fire photography. And in 2008’s The Flannigan Affair, a simple story gets destroyed by the insistent self-referencing of a faulty narrator. Electric Company has conjured a pantheon of anti-heroes, each hobbled by his or her own artistic inquiry. Critics and audiences have been enamoured, the company has won a number of prominent awards, and Collier and Young are two of the country’s most sought-after theatre artists. Collier will join Canadian Stage in September as its associate artist.

Young says he sometimes wakes up and thinks, “I should be grateful for every second of this.”

“But we’re not,” Collier says. “We can feel incredibly trapped by our projects. There’s this thing, this creation, hanging over us. And we are in service to it.”

Their obsession with the process of art making shows up in the works. Recording technologies like photography, video, and film appear in many of their plays. “Our interest,” Young says, “is that tension between the flat image, which is an ideal, edited thing, and the accidental, living, breathing presence of the body. How our bodies are in conflict with those ideal images. How our experience of life is so much about a constant negotiation with fixed representation.”

The pair’s greatest success to date is an adaptation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit, which had its premiere in 2008 in Vancouver and is being remounted this spring at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. The company’s fascination with media reaches a blistering apotheosis here. Three damned characters find themselves locked in a hotel room together; this is hell (“L’enfer, c’est les autres”). Collier depicts the afterlife as a wholly sealed encasement monitored by a set of video cameras. The actors are out of the audience’s view, and are only seen via screen projections. Their torment and their remove from the living, breathing third dimension is claustrophobic and profound. Just as John Cage’s 4’33” makes the audience awake to its own shuffling and coughs by offering minutes of silence from the pianist, Collier’s No Exit forces her audience to feel the thrill of being alive in a singular time and place—indeed, of being alive at all.

Even Sartre, who depressives and misfits pin up as their idol of disassociation, was convinced by the events of World War II that he was part of the tide of human life. In 1945, he declared that “existentialism is a humanism.” Collier’s staging allows her existentialist No Exit to still be human and full of heart, precisely by denying us the presence of the actors’ bodies. There’s nothing uplifting, per se, about No Exit, but there’s a certain joy by comparison.

And Collier does not condemn her entire cast to hell. Young played the bellhop—the only character present onstage who inhabits the middle ground between the vice-like crunch of artifice (the souls trapped on the screen) and the unscripted freedom of real life (the souls in the audience). Throughout the performance, he held up cheeky cue cards, postmodern footnotes to Sartre’s dated text. He seemed to be having a good time.

People involved told Collier the audience wouldn’t be able to connect with the material; they often tell her that. But the work enjoyed a sold-out run in Vancouver, and won the Jessie Awards for Outstanding Production and the Critic’s Choice Innovation Award.

Those trapped hell mates represent another aspect of Electric Company’s obsessions. Traditional dramas parachute the audience into fully formed worlds—a system. But what if that system were a trap? A bunker, say, outside of which lies real life? In reference to that most recent play, Tear the Curtain!, Collier talks about “the tyranny of narrative” the way characters in The Matrix talk about waking up and becoming unplugged. The narratives we live by—our marriages, or the jobs we mindlessly attend to—are only real because we decide to truck along with their rules. But can we ever step outside our stories? And if we could, would we be wiser for it? Would we be happier?

According to Collier, “We all, through faith or whatever, have these narratives, these structures, that allow us to get through our days.”

“Narratives save the day,” adds Young. “They restore sanity. Even the pure escapism of Hollywood films—they’re a healer. They give us the potential for surviving life.”

Somewhere, amid the increasing distractions of success, the company has begun work on another production, a staging of Tad Mosel’s All the Way Home, a family drama set in Tennessee, in which children deal with the death of their father. Collier wants the actors to never leave the stage. As their scenes are done, some of the characters will retire to bedrooms or hallways, but remain in plain sight. What’s more, Collier intends to have the audience sitting on the stage itself.

“It’s about intimacy, really,” says Young. It’s about creating a moment when “real life” and artifice can become confused. The solace, the comfort of art consumption is as familiar a trope as it is a baffling one. Years ago, when their daughter Azra walked into an empty theatre with Young, she looked around and told him, “This feels like home.” And, indeed, the very sensitive among us seem to become most ourselves in the very environments where we drop away selfhood and invest in some mysterious invention.

At their heart, Young and Collier’s plays offer two consoling pieces of advice for those wayward, big-hearted folk. One: stories can protect you from the harshness of experience. And two: you can always choose to step outside those stories and live in the lusty, buffeting, dangerous world.

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.