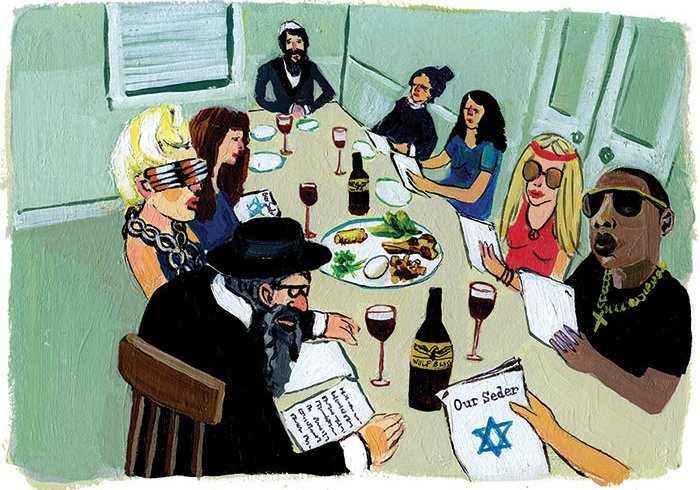

The great Max Weber built modern social science on the backs of the major faiths, yet he remained, in his words, “religiously unmusical.” I always recall that phrase when I’m conscripted into religious events, which, because I’m Jewish and have a mother, occurs several times a year. We sit around the table, my family and I, battling through medieval Hebrew prayers we only vaguely comprehend, enacting rituals at once ancient and vital. An African-born clan whose shtetl origins in rural Lithuania stand to this day, Judaism is who we are. There is, however, no music in our practice.

Last Passover was particularly dissonant. Why was this Seder different from all others? For one thing, my cousins are parents now; everywhere, screaming babies bobbed away in Scandinavian contraptions. My mother and aunts are suddenly senior citizens, and the responsibility of holding these events, I realized, would soon fall on my generation. We will have to deck the Seder plate and chop the herring, literally keep the faith. These conundrums are as old as the Diaspora itself.

My cousin Janine, the flower child, resolutely took the family’s spiritual reins in hand. Bouncing a toddler on one knee, she read from a photocopied adaptation of the Haggadah—the literary component to, and the liturgy for, the Seder dinner ritual—named Our Seder. Normally, we pick our way through a ragtag collection of Haggadot, no two the same, each with its own awful translation or oddball anachronisms. Our Seder was a different species altogether. It opens with a twist: “And while Passover is a Jewish holiday, it is not only for Jews. We welcome our non-Jewish brothers and sisters to our celebration of liberation.”

Despite my non-Jewish girlfriend sitting beside me, this set my teeth on edge. Last I checked, Passover was about the Jews fleeing Pharaoh in sandals, carrying nothing but bags of crackers. “And let us remember,” continued Our Seder, undaunted, “that we retell the story of suffering not to dwell on the past but to use its lessons to make ourselves more sensitive and responsive to the needs of others and of our inner selves.” What was this—Eat, Pray, Kibitz? The plagues visited by God upon the Egyptians are augmented with a list of modern woes, among them “greed,” “pollution of the earth,” and “ignorance.” Then Our Seder asked us to sing Ed McCurdy’s anti-war ditty “Last Night I Had the Strangest Dream.” I braced myself for the ceremonial donning of tie-dye.

As the night wore on, Our Seder seemed to me more and more like a gargantuan act of relativism by way of liturgy. Its woolly Boomer liberalism was fogging my brain, and I wasn’t alone in this. But what was it about Our Seder that so troubled a family of over-educated, organic arugula–eating Jews? I stared down at my own illustrated Haggadah, a bar mitzvah gift from my grandfather, and mulled over the fact that there was no other work of literature I’d read so often, outside a couple of Tintin titles. And yet I couldn’t tell you what the plot was, whether there was one, or how it fit into a larger cultural framework. With the groaning of internal machinery I had long thought decommissioned, a minor spiritual crisis was under way. What did the book mean? And what answers did Our Seder hold for my generation, flailing through faded rituals, trying to remain whole?

Several months later, after walking a dozen sweltering blocks through a New York heat wave, I arrived at Assouline Publishing in Chelsea, and sat before an ur-Haggadah. Printed on vellum so luscious it practically stank of money, the book was heavy enough to bench-press, and so exquisitely produced that I assumed it would wipe Our Seder from memory. But it took mere moments to realize that the Assouline Haggadah and Our Seder—retailing at $550 and bubkes, respectively—were sibling texts locked in a filial battle, clamouring for approval from some unseen, shadowy patriarch.

“Haggadah” means “telling.” Reading it fulfills the scriptural commandment in Exodus to “tell your son” about the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Egypt, and its recitation kicks off the week-long festival of Passover. In the Diaspora, the Seder takes place on the first two nights of the festival, and the Haggadah serves as the manual for this labyrinthine gorgefest. The proceedings involve the eating of unleavened bread (matzo), bitter herbs, and other symbolic markers of our afflictions in Egypt. There are hymns, there are prayers, and we cap it off with the kiddies searching for the afikoman, a piece of matzo hidden by the leader of the Seder. (This summary undermines the sheer length of the process—in excess of four hours if it’s done properly.)

Lurking at the Haggadah’s heart is the story of Exodus, which is to the Bible what Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction is to rock—so strident it makes the rest of the canon superfluous. Exodus doesn’t create the Jewish God; it complicates Him. In simultaneously freeing the Jews from bondage and killing every male first-born Egyptian, He becomes unfathomable. Furthermore, Exodus performs two important and lasting sociological functions: it creates Jewish exceptionalism (We were chosen! And saved!), and it defines Jewishness as an exilic condition.

The Haggadah doesn’t tell the story of Exodus so much as it depicts five rabbinical sages exegetically parsing it via Deuteronomy. Rabbis Eliezer, Yehoshua, Elazar ben Azariah, Akiva, and Tarphon spice up the biblical tale of the flight from Egypt by arguing over the minutiae of the Passover rites, which were originally compiled in the Talmud, the Jewish book of religious laws. We’ll avoid the scholarly bickering about when this occurred (very roughly, 200 CE), but one thing remains certain: the Talmud, and the Haggadah along with it, was a response to a catastrophe so great it threatened to destroy a people.

In 66 CE, when the Roman general Vespasian swept into Jerusalem, Judaism was a cultic, oral religion, with Herod’s massive temple as its lodestar. Everything happened in the temple complex. Four years later, Vespasian’s son Titus razed it to the ground. “Where was God under the rubble? ” wondered the Rabbis. “How to praise him now that the temple was gone? ” The sages agreed: Jews would have to become a people of the book, or they would disappear.

In a dazzling feat of spiritual and scholarly bravura, they compiled the Talmud, the text that has defined Jewish life for almost eighteen centuries. It meticulously redacts generations of oral religious injunctions, explains them, justifies them, chews them into a (mostly) digestible intellectual cud. The Talmud’s first compilers, the early rabbinical scholars called the Tannaim, had one principal concern: to establish that after the destruction of the temple, nothing had changed. It portrays, in one historian’s words, “the old in light of the new, and the new in light of the old.” The Talmud turned action, like the Passover sacrifice of the paschal lamb ordered by God in Exodus, into symbol. The Haggadah is conjured from the same alchemical matter.

The assouline office, cool when I arrived, was now as fetid as a shvitz. On my right sat notes on Our Seder; on my left, the hulking Assouline Haggadah. I thought of the farrago of food stained Haggadot that sits on my family’s Seder table; almost 7,000 different editions were printed between 1900 and 1939 alone, and we own a clutch of them. Ballasting this, a millennium of Haggadah history: handwritten, embossed, gilded, printed, hidden, desecrated, burned, saved. The Sarajevo Haggadah, perhaps the most famous example of how the text has weathered the centuries, was born in Spain around 1550, cast out during the Inquisition, reclaimed in Eastern Europe, hidden during the Shoah, recovered, and then hidden again during the Bosnian war. It has been touched by devotion and bravery and tragedy for five centuries, and it remains triumphantly intact.

For its part, the Assouline Haggadah is an Orthodox edition—it does not, for example, include Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way.” It does, however, have its idiosyncrasies. The commentary by Rabbi Marc-Alain Ouaknin, a philosophy professor by day, includes generous dollops of Jung, Lacan, Kierkegaard, Hegel, and Kant. Presumably, Assouline didn’t splurge on vellum for the didactics, but rather for the other half of the package, French painter Gérard Garouste’s illustrations, which mash up Marc Chagall and Maurice Sendak. They are out of time and place: oneiric, eerie. Never maudlin but properly melancholy, they trace the line between liberty and loss. Garouste, whose work suggests a deep understanding of Jewish history, paints a Haggadah that is an acknowledgement of the works that have come before. It is conscious of its Haggadah-ness.

The first extant version of the Haggadah was written almost 1,100 years before the Assouline edition, unearthed in a manuscript of a siddur (prayer book) compiled by Saadia Goan in the tenth century. Before this, the liturgy came to us from the Talmud. The Talmud’s redactors did not work in a vacuum; they were thoroughly alive to the Greco-Roman philosophical and literary developments of the day. Indeed, the compilers of the Seder (and thus the eventual Haggadah) were heavily influenced by symposium literature, a then-booming genre, which is sort of like the contemporary Vatican deciding to reboot Mass in light of locavore bestsellers.

Symposium literature, over the course of its history, devolved into what Philo, in De Vita Contemplativa, dismissed as an orgy of flute girls, juggling girls, effeminacy, and overindulgence. At its best, the genre produced its share of civilization-defining classics, all philosophizing on how best to eat, live, and admire young men’s torsos. Plutarch described the symposium as “a communion of serious and mirthful entertainment, discourse, and actions.” The Seder ritual is firmly of this tradition.

In Plato’s Symposium (renamed Horny, Drunk Guys Invent Philosophy in a recent blog post titled “Greek Classics: Better Book Titles”), a reclining Socrates is washed by a servant, bowdlerized in the Haggadah as the urchatz, the ceremonial washing of hands. In Deipnosophists—a fifteen-volume epicurean opus that reads like a philosopher’s pitch for a Food Network show—Athenaeus refers seven times to lettuce, which was incorporated into the Seder meal as the eating of bitter herbs. Afikoman is thought to derive from the Greek term for “dessert”; in Jewish tradition, it becomes the post-prandial hunt for matzo.

For those not sharing in the grub and the libations, the symposium was about the lobbing of softball questions, posed to some of history’s greatest minds. “Does the land or sea offer better food? ” Socrates might have been asked. Or “Why is hunger allayed by boozing, but thirst increased by eating? ” Alternatively, “What’s up with the Pythagoreans hating on fish? ” The Haggadah offers its own version of this mind-bending parlour game: the asking of the four questions. At our last family Seder, two-year-old kids squealed out, “Mah nishtanah, halayla hazeh mikol halaylot”—“Why is this night different from all other nights? ” Cue the five rabbis, heirs to Plato and Plutarch, and their lengthy lucubrations.

The Haggadah’s redactors, in a brilliant act of literary transmogrification, took the mechanics of the symposium ritual and animated them with symbolic and didactic meaning. Thus, the symposium standby of bitter veggies dipped in salt water—or karpas—comes to represent the meagre food of slavery, marinated in the tears of the Jewish people. The profane was reimagined as the sacred.

Despite this venerable literary pedigree, one still wonders why the Haggadah has proven so durable. To my mind, this is less a theological question than a literary one. Aesthetically speaking, You’d figure it must be one hell of a read to have survived the vicissitudes of history—Jewish history in particular. Aesthetically speaking, not so much. It’s as boring as Moby Dick, as didactic as Candide, as shoddily translated as many of the Russian classics, with characterizations as thin as Freedom’s. Most egregiously, it devolves into a panegyric for a murderous deity. Hey, welcome to religion!

On the plus side, it’s interactive, which is a big deal in publishing. Any book that involves compulsory wine drinking must be a winner. And performed properly, a rhythm emerges. Kiddush, the blessing of the wine; the story of Exodus, including the hymn “Dayenu”; the meal; grace. It reaches the height of its power when it asks us to intone the ten plagues—Exodus’s terrible denouement. We each dip a finger into our wineglasses and deposit a scarlet droplet on a side plate. (As Jews who imbibe, we use Cab Sauv rather than Manischewitz.) Only the Hebrew adequately reveals the poetry of this ritual:

Dum; Tzfardayah; P’niym; Arov; Dever; Sh’chiyn; Barad; Arbeh; Choshech; Makat B’chorot.

Locusts. Darkness. The Slaying of the First-Born. Jews stand forever on the winning side of this act of celestial wrath, and have for centuries intoned these same words in their homes, linking them to the ruby redness of blood, absorbing them into selfhood. Garouste’s dreamscapes in the Assouline edition are dead on: the Haggadah mimics what it must feel like to wake after generations of bondage. The book captures the sense of sleepwalking through slavery, and the seismic jolt of being born again as a free person. In this, it is profoundly human—and, if you’ve happened to turn on the TV of late, startlingly germane.

The assouline haggadah, 550 bucks’ worth of luscious, high-end paper product, proves the Haggadah’s staying power. But so does Our Seder, published on a photocopier, bound with staples. And yet, both also present a threat to the text’s life: the Assouline Haggadah because it fetishizes tradition; Our Seder because it bows so slavishly before the altar of modernity.

In the latter instance, can the Haggadah handle, among other indignities, Ed McCurdy’s folksy trespass? The answer, historically, is “sort of.” Most Jewish prayers—even the centrepiece of the liturgy, the amidah, or standing prayer—took almost a thousand years to develop. Jewish religious writing, at least until the hardening of Mishnaic scholarship in Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, was not quite Hindu absorptive, but it wasn’t San Quentin restrictive either.

But these ain’t the Middle Ages. How are modern readers supposed to relate to the mores of a time in which sages were not blogging on Huffington Post? Surely it’s reasonable to jazz up our liturgical documents, to make them current, to plug them in? Our Seder calls for an orange on the Seder plate, to represent “those marginalized by traditional Judaism,” by which it means women and gays. Nice thought. Judaism’s two main cohorts, however, are divided on this. Orthodox Jews would say, “Sit tight, little ladies.” While Reform has lesbian rabbis presiding over Passover services.

By dint of being Reform, Our Seder has an existential predilection for modernizing flourishes. Its relationship with tradition is radical rather than reactionary. Intellectually, I cannot dispute this position. Aesthetically and culturally, subbing Appetite for Destruction for campfire songs is, as far as I’m concerned, a losing gambit.

Our Seder troubles me in part because it writes the sensibilities of previous generations out of the picture, as if they didn’t exist. It is also painfully unhip. (Replace Ed McCurdy with Jay-Z, and suddenly you’d have my attention.) Critically, Our Seder disintegrates at the very point where literature meets liturgy, where ritual intersects with the written word. The Haggadah’s thematic consideration is freedom; Our Seder’s main concern is values. The two don’t necessarily jibe—especially if you consider liberty an absolute value. Rabbi Ouaknin of the Assouline Haggadah writes, “It is a paradox of liberty that it can only be attained within the framework of order, of rules, of words and symbols of extraordinary precision.”

Situationalists, anarchists, and Julian Assange may disagree, but there it is. Planted into the book is the idea that freedom can only arise through a formal system. In the Haggadah’s case, contemporize, and the codified gestures and culinary histrionics stop making sense.

Our Seder presupposes levels of empathy, sensitivity, and general kindness that humanity is at least six evolutionary cycles away from achieving. But it bevels the edges off Exodus and relaxes the tenets of the Seder, without properly understanding those tenets. In this, it undermines the essence of the document it professes to improve. Herein lies the tragic paradox: the more we reform, the better we become, but the less we remain who we are.

By consensus, my family and I will not be reading Our Seder this Passover. Nor will the Assouline Haggadah be hoisted by crane onto the table. We will keep to our tradition of reading from the Babel of assorted, yellowed Haggadot, translated by writers with only an incidental knowledge of modern English. There is something reassuring in all that confusion. The Haggadah links contemporary practicioners of Judaism—along with eighteenth-century Jews, medieval Jews, and Jews of the fourth century—to second-century Hellenistic culture, and to each other. The assortment reminds us, also, that Jews are not one coherent body, but millions of individuals linked by history and tradition; that to disagree on perspective is fundamentally Jewish; that the Haggadah itself depicts five recalcitrant rabbis arguing over specifics. Discourse is the foundation of rationalism. Without it, we’re doomed.

No doubt about it, the Haggadah is a problematic text. It tells Jews that they are exceptional, and it puts a premium on Jewish life over the lives of others. It sends us into exile; it links us forever to Israel. (Next year in Jerusalem, it insists.) But the Haggadah performs two vital functions: it reminds us of the price of liberty, and reinforces the importance of tradition. It is up to us to understand that tradition can be liberating, because it frees us from the tyranny of the new—but only if that tradition is properly understood. In my experience, no two families’ Seders are the same. And that’s fine, so long as we acknowledge that we are negotiating the same text, the same order, and thus the same history.

The Haggadah ends with the opening of the door for the errant prophet Elijah, whose arrival will precede that of the Messiah. We set a place for Elijah at the table, and we pour him a cup of wine—he is another Jewish absence, another erasure. We do this for him because the Talmud is unclear on whether the Passover laws call for four cups of wine or five—so, a compromise. Wine for the missing prophet, who will herald God’s arrival. It’s a nice gesture. One day, maybe, I’ll hear the music in it.

This appeared in the May 2011 issue.